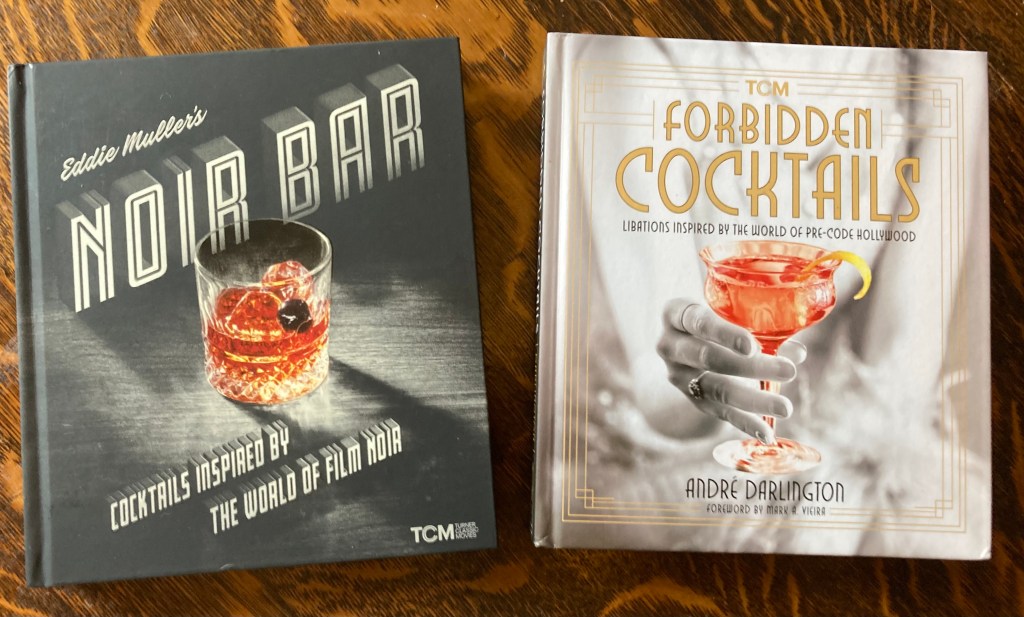

I didn’t conceive of it as such, but my “Drink & a Movie” series is a fair approximation of my personal cinema and cocktail canons because (predictably, in retrospect) I have mostly chosen to write about my “go-to” directors and ingredients and scenes and techniques, the ones I’ve spent the most time thinking about and which have therefore played the biggest roles in shaping my point of view as a cinephile and drinker. My tastes are constantly evolving, though, and to conclude my three-post-long celebration of crème de cacao I’ve selected two new discoveries from the past few years.

Shortly after I watched Black Sheep for the first time, I talked about it first in an “Ithaca Film Journal” home video recommendation as “total catnip for me,” then again a few months later in my “Top Ten Movies of 2023” post as “the most fun I had with a movie all year.” Here’s a picture of my bare-bones 20th Century Fox “Cinema Archives” DVD copy:

Unfortunately, although I originally saw this film on the Criterion Channel as part of a collection called “Directed by Allan Dwan,” it doesn’t appear to be streaming anywhere right now.

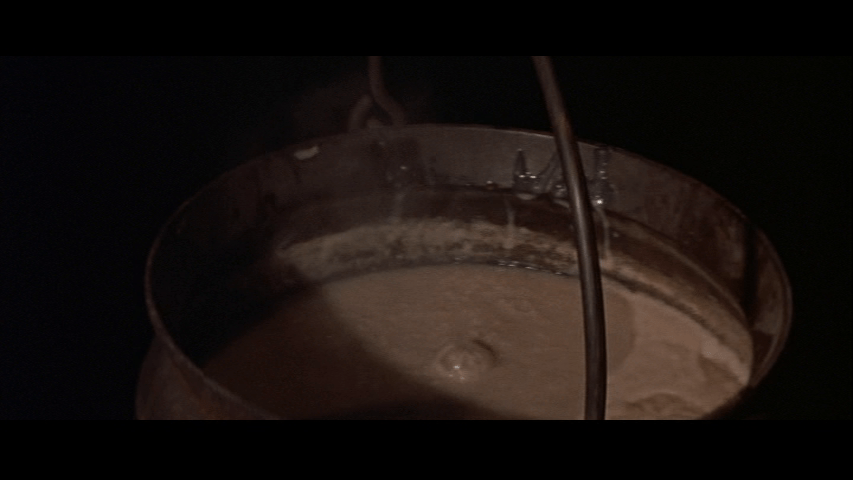

One of the things I found so delightful about Black Sheep are the old-school drinks heroine Claire Trevor’s Janette Foster orders: she asks for, in sequence, crème de menthe, a crème de menthe frappé, and Dubonnet. I wanted to offer a more complex alternative to Janette’s usuals like I did with the sweet vermouth on the rocks with a twist ordered by Andie MacDowell’s Rita Hanson in my Drink & a Movie entry for Groundhog Day, and I quickly settled on the Chapuline, a delightful variation on the grasshopper created by Toby Maloney of Chicago’s The Violet Hour. He specifically calls for green crème de menthe, but does so while making a joke related to presentation: “the white pales in comparison.” I’ve never been able to find the bottle by Marie Brizard he recommends and every verdant variety that *is* available in Ithaca tastes unbearably artificial in comparison to Tempus Fugit Glaciale, so that’s what we went with. In addition to tasting much better, I submit that it also looks just fine in this yellow glass we picked out to serve it in. Here’s how we make it:

1 oz. Crème de cacao (Tempus Fugit)

1 oz. Crème de menthe (Tempus Fugit)

3/4 oz. Pisco (Macchu Pisco)

1 oz. Heavy cream

Shake all ingredients vigorously with ice and double strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with a spanked (to release its aromas) fresh mint leaf.

As he notes in The Bartender’s Manifesto, Maloney’s goal was “to prove that [he] could take a gauche drink and make it at least interesting, at best delicious.” Mission accomplished! The first thing you notice is its beautifully silky texture. The flavor that pops is peppermint immediately followed by chocolate–the effect would be almost exactly like eating a York Peppermint Pattie except that there’s also a burn which resolves into grape on the finish, as if the drink was morphing from a grasshopper to a stinger, the other classic cocktail most commonly associated with crème de menthe. You wouldn’t get this with a barrel-aged spirit like cognac, obviously, so the choice of pisco is quite brilliant!

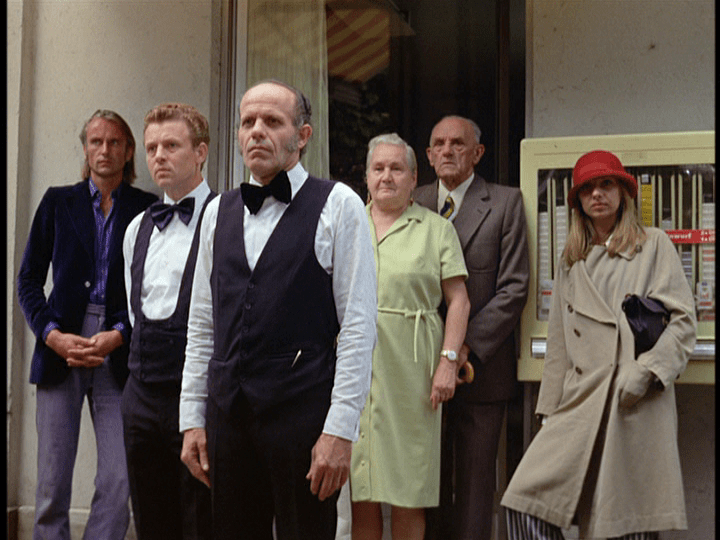

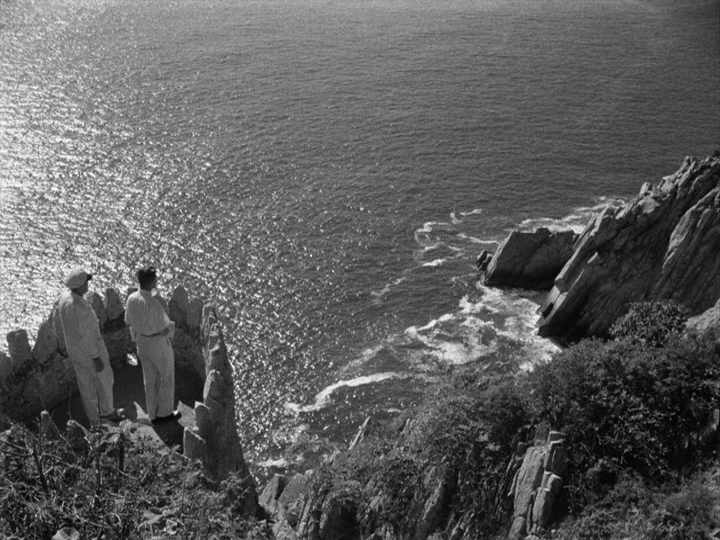

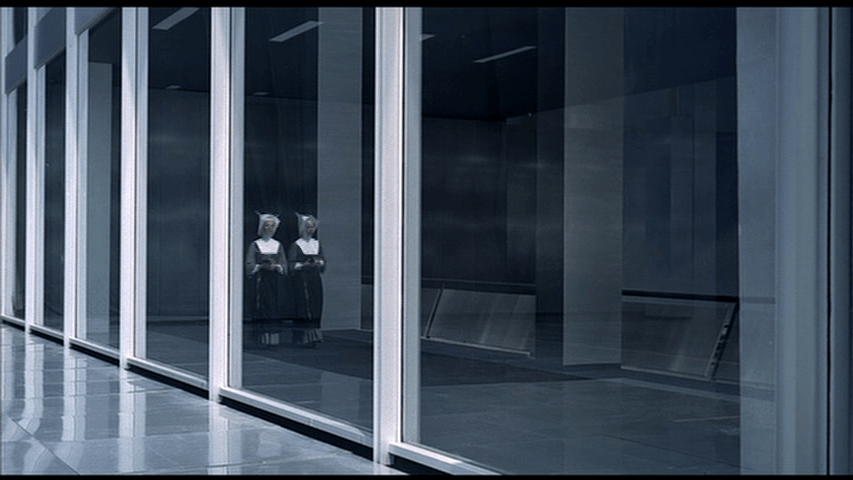

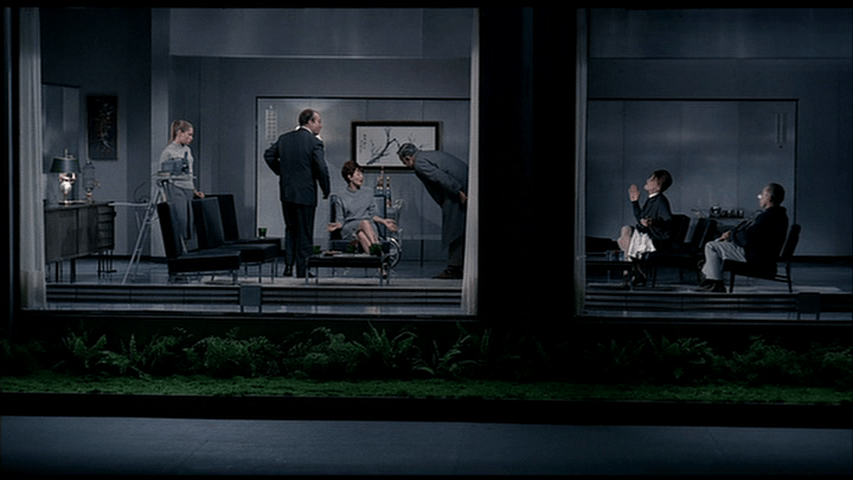

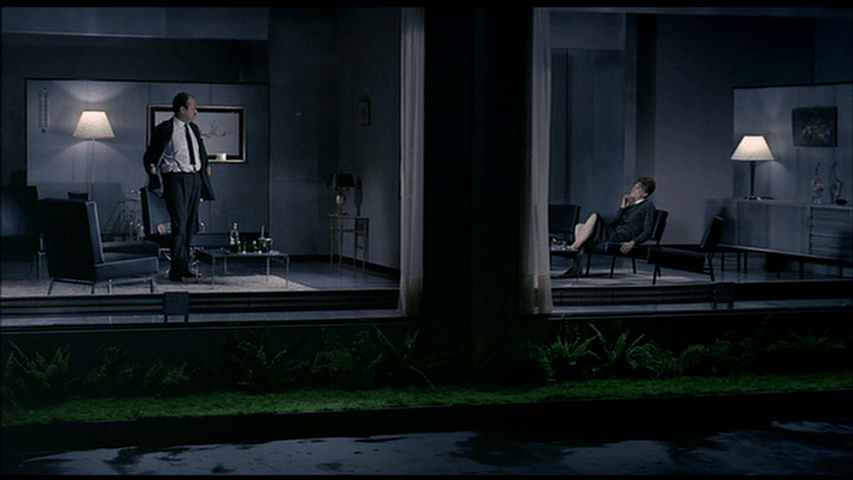

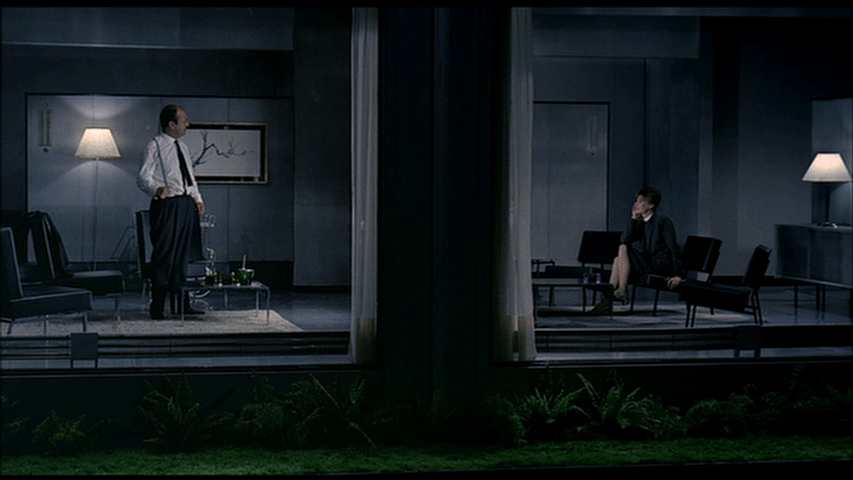

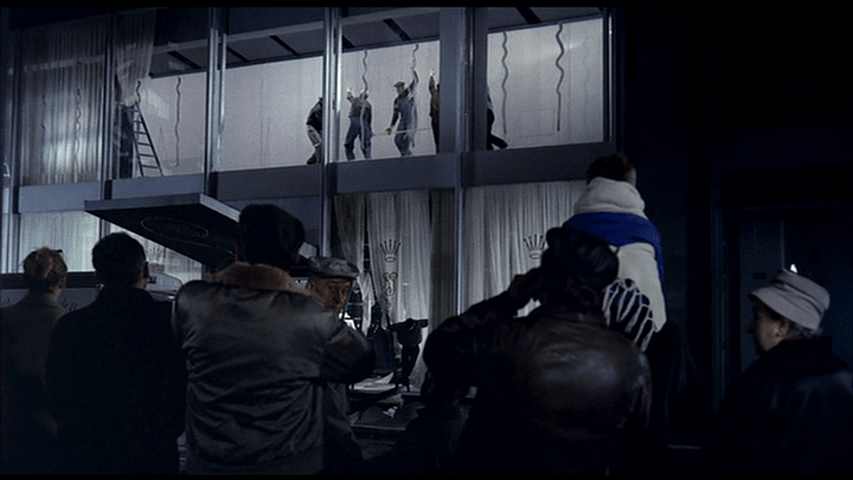

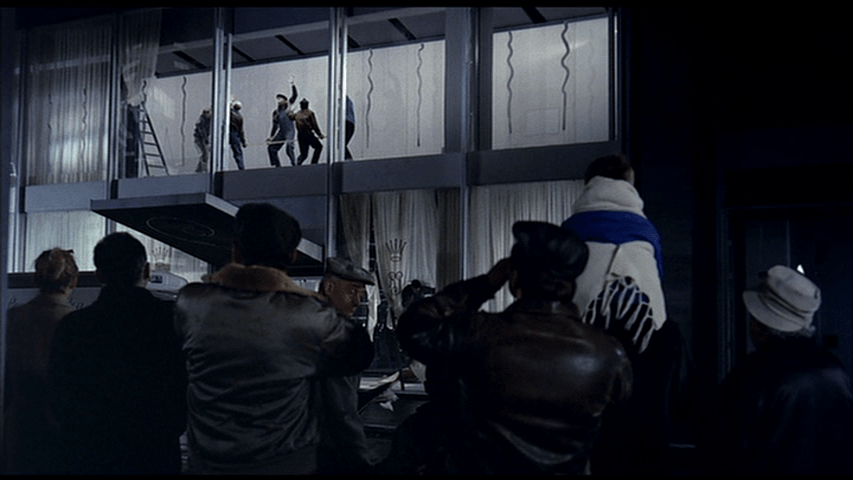

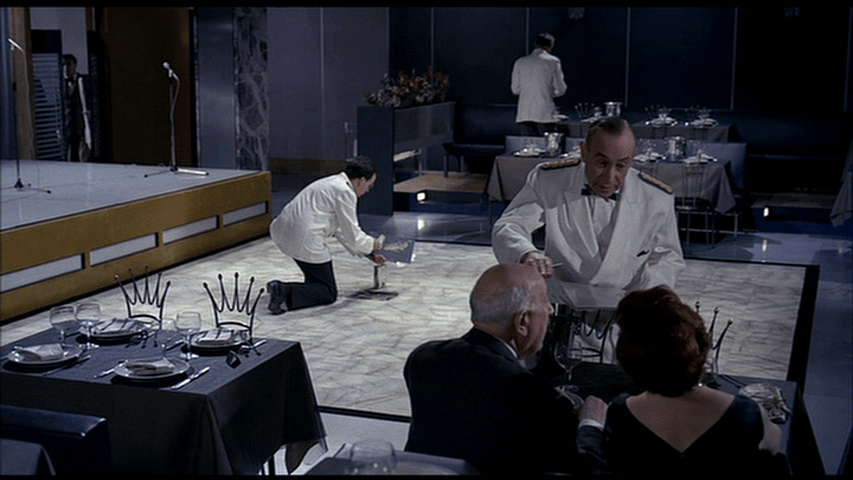

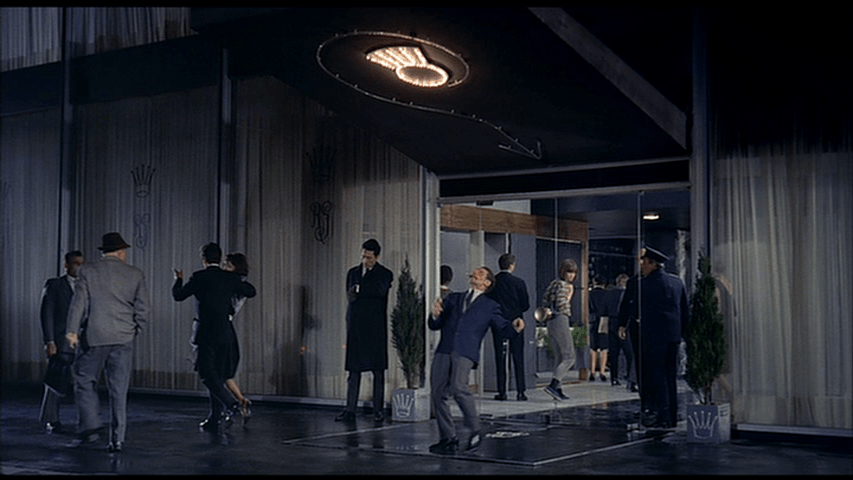

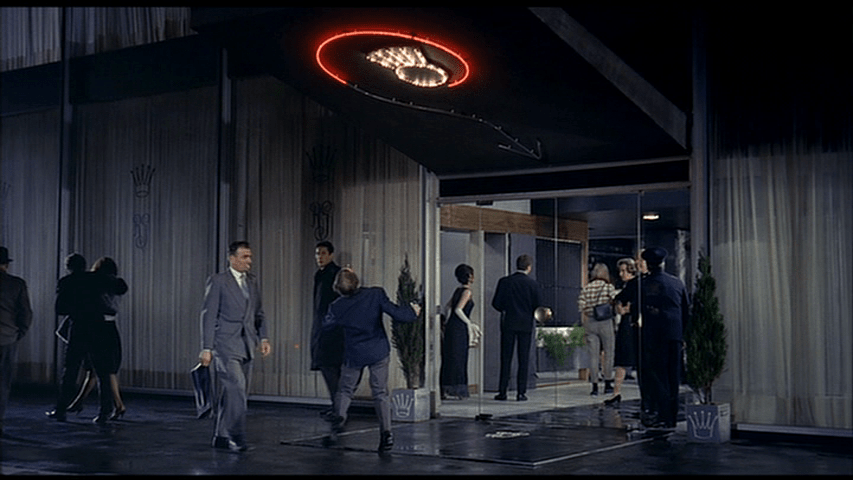

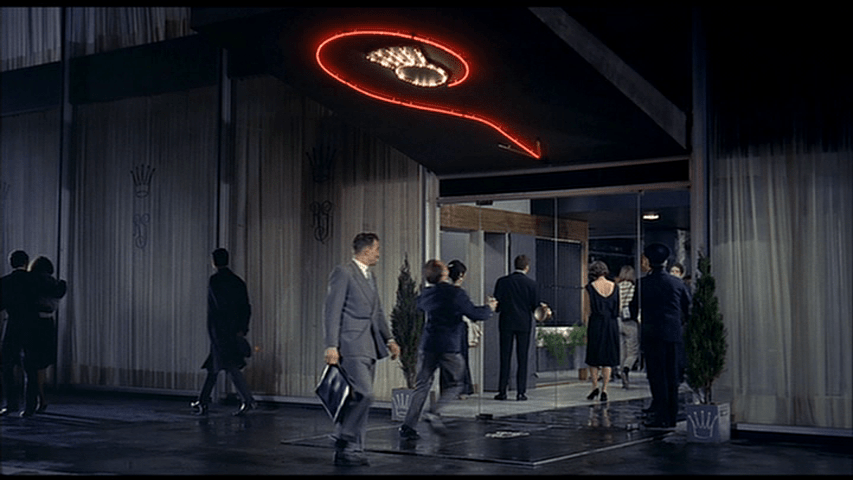

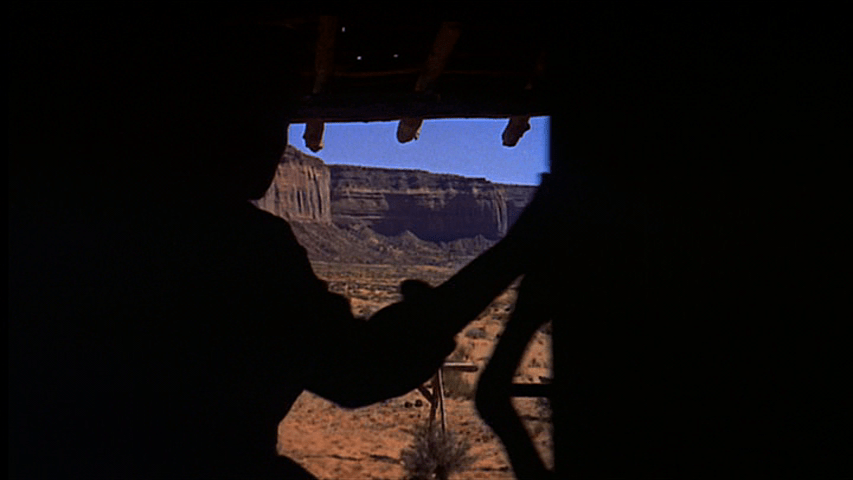

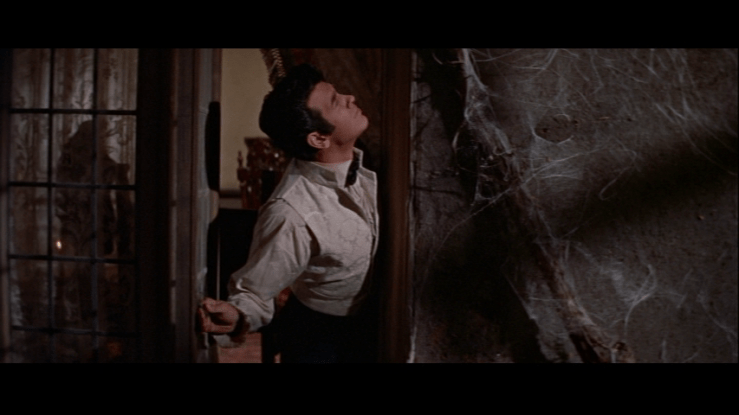

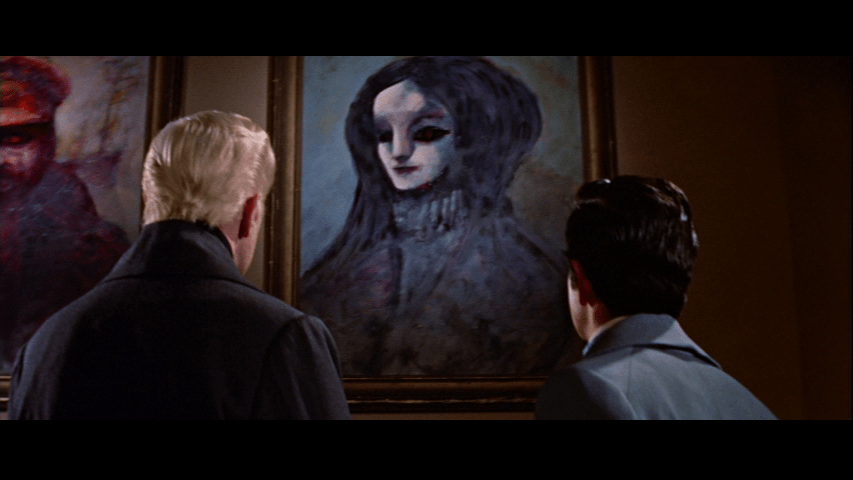

Maloney’s recipe includes instructions to shake “like it owes you money,” which is actually a pretty excellent segue into discussion of Black Sheep since income, like the film’s camera movements, represents both freedom and confinement for its protagonist John Francis Dugan (Edmund Lowe) and the other characters. As Frederic Lombardi writes in his book Allan Dwan and the Rise and Decline of the Hollywood Studios, “the opening shots of the film give a full sense of the great breadth of the ship Olympus but as the story unfolds, there are increasing attempts to restrict the space in which Dugan can move, so that he must literally know his place.” To start at the beginning, an introductory montage provides a tour of the ship’s first-class spaces:

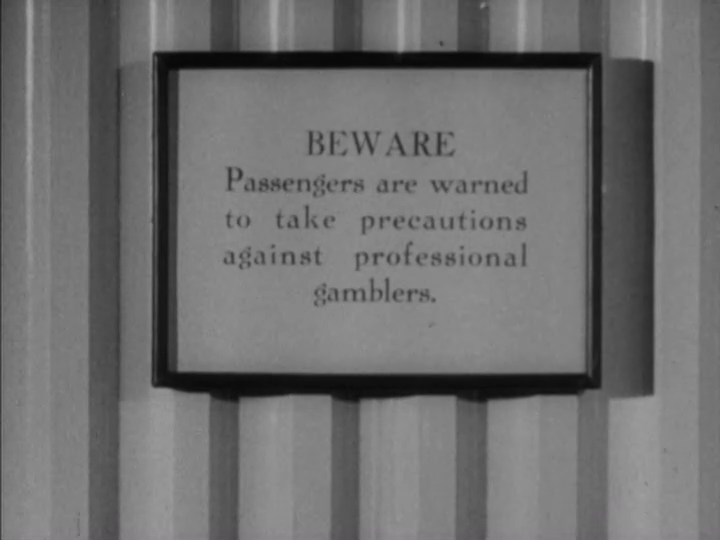

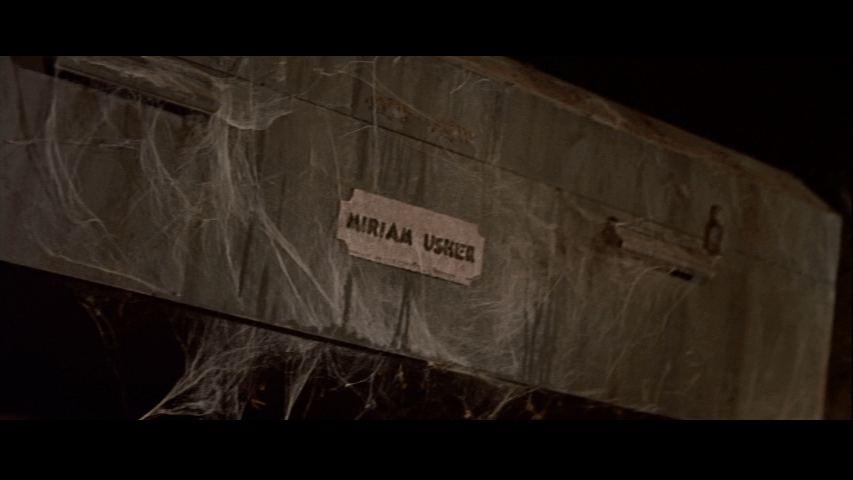

Before the gliding camera comes to rest on this sign:

And then goes tumbling down the stairs:

Moving at a much faster pace than it did earlier, cinematographer Arthur Miller’s camera now repeats its double-exposure trick to show us we’ve been taken down a notch to second class:

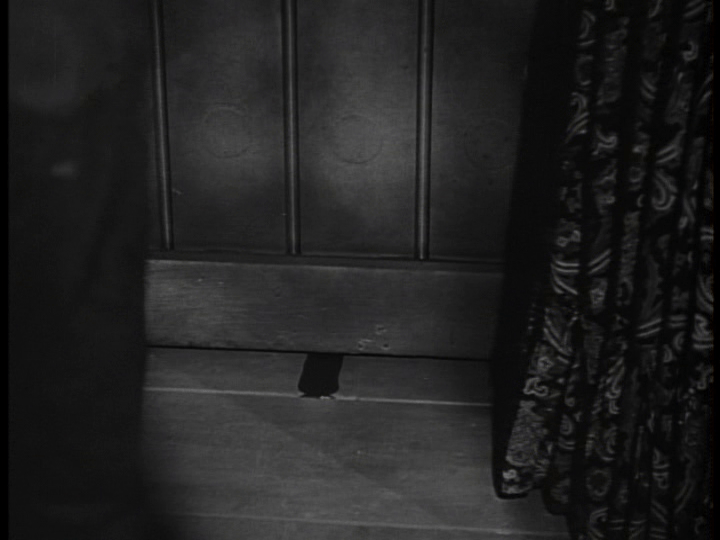

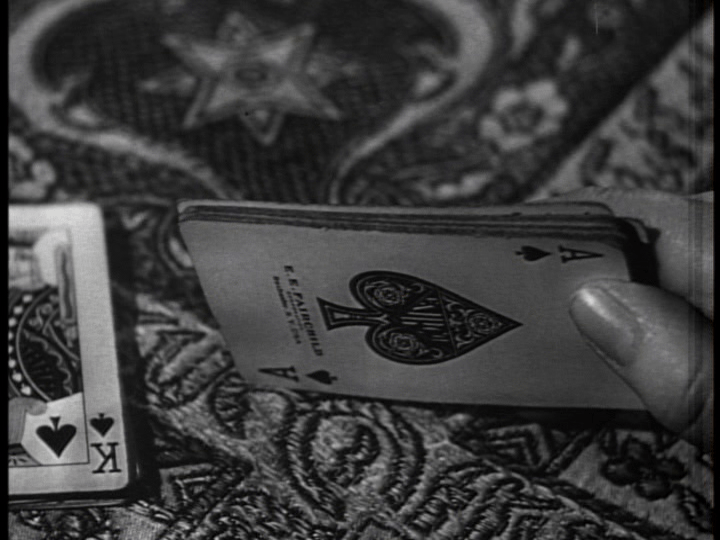

Before it finally stops on a sign and cuts to Dugan playing solitaire:

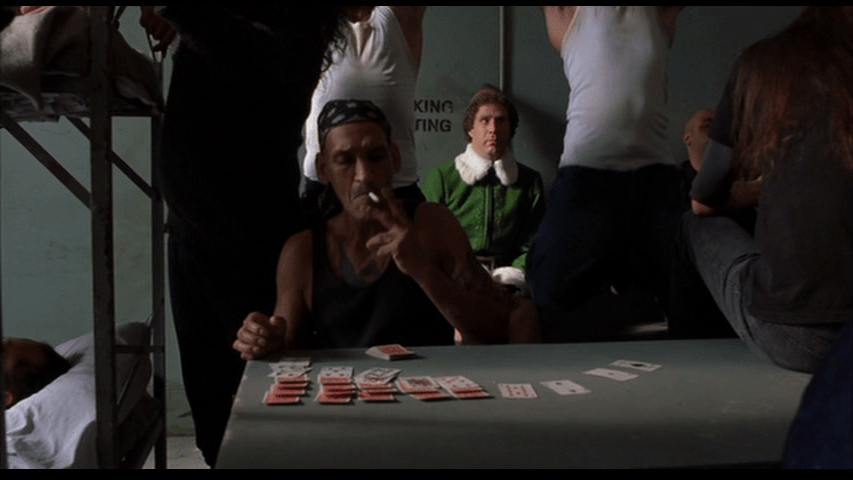

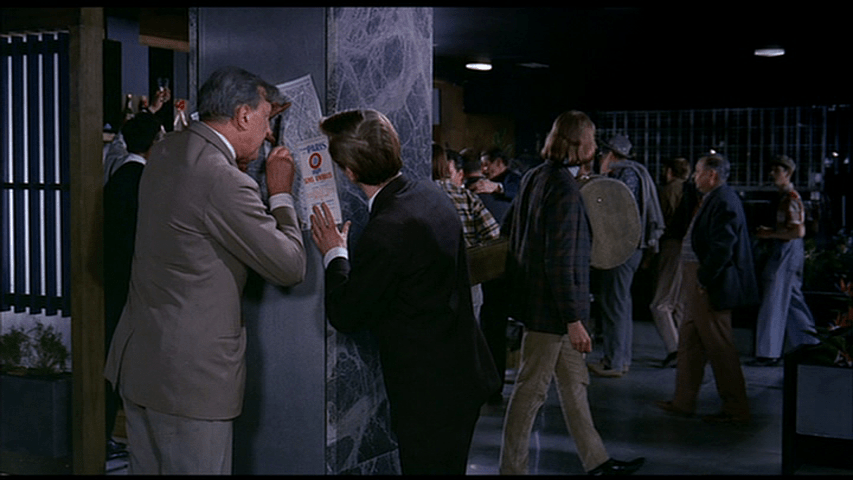

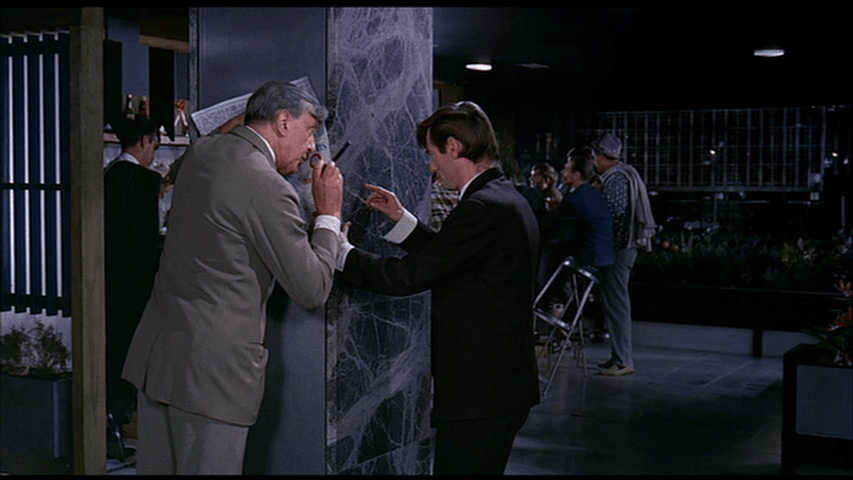

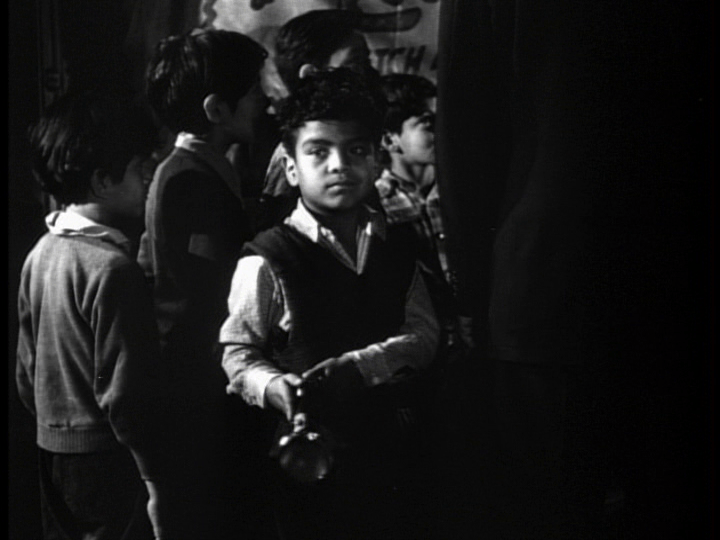

In just the first of many examples of what Fernando F. Croce calls Black Sheep‘s “limpid storytelling,” our logical assumption that he must be one of the sharps that the people on board the Olympus are cautioned to be wary of is confirmed by the two shots which follow him looking up from his game at his fellow denizens of the second-class smoking room.

First a woman indignantly responds to her companion’s suggestion that they play bridge for a tenth of a cent per point by saying, “I should say not! I lost 55 cents at a twentieth last night. I’ll play for a fortieth or nothing.”

Then one man responds to another’s suggestion that they play checkers by saying, “I don’t mind if you don’t play for money.”

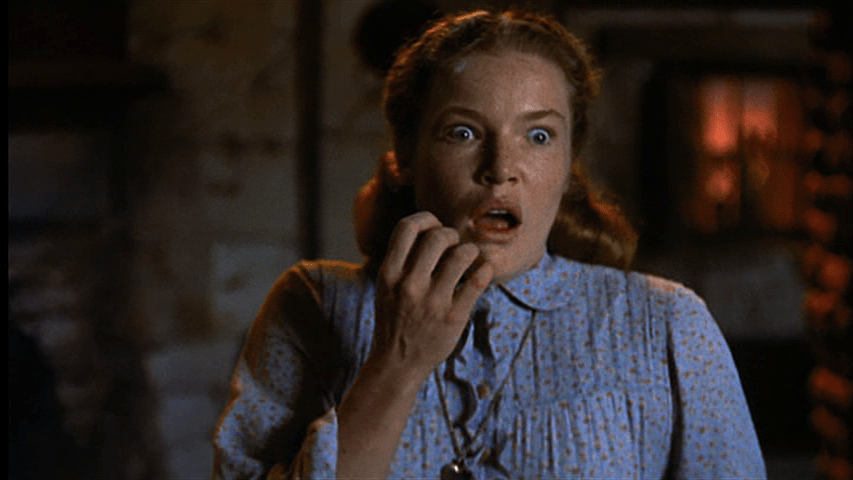

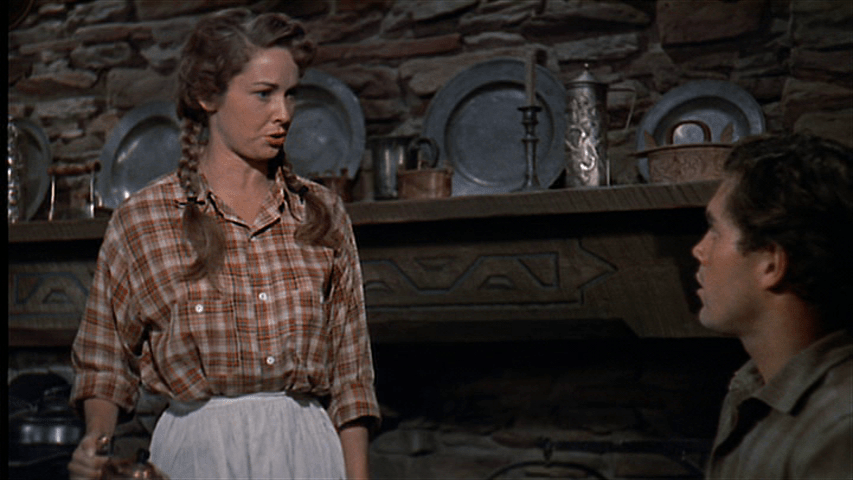

Dugan shakes his head and returns to his game, but is soon distracted by an offscreen clicking noise which a quick tracking shot soon reveals to be caused by Foster’s vain attempts light a cigarette:

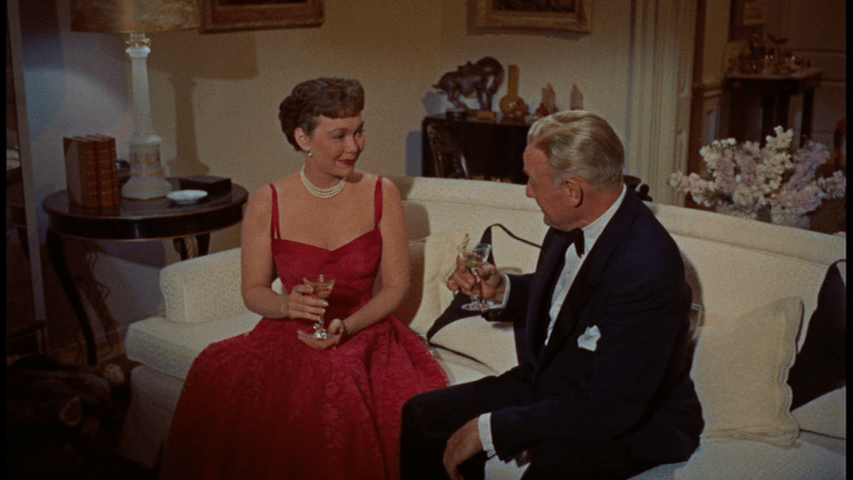

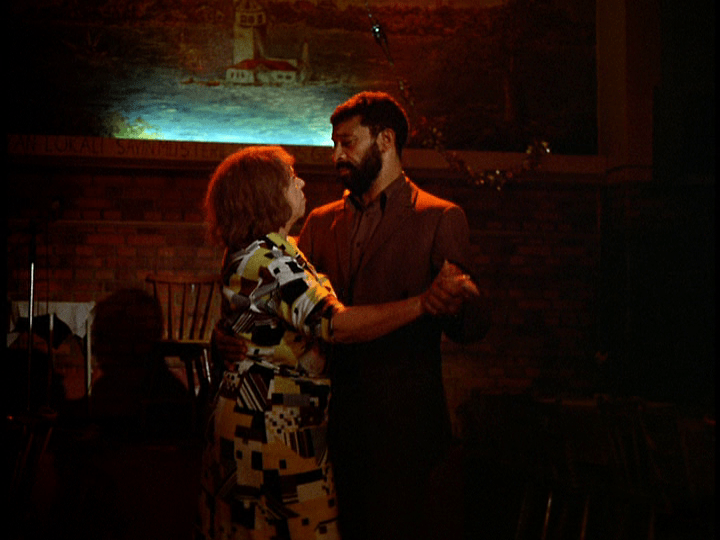

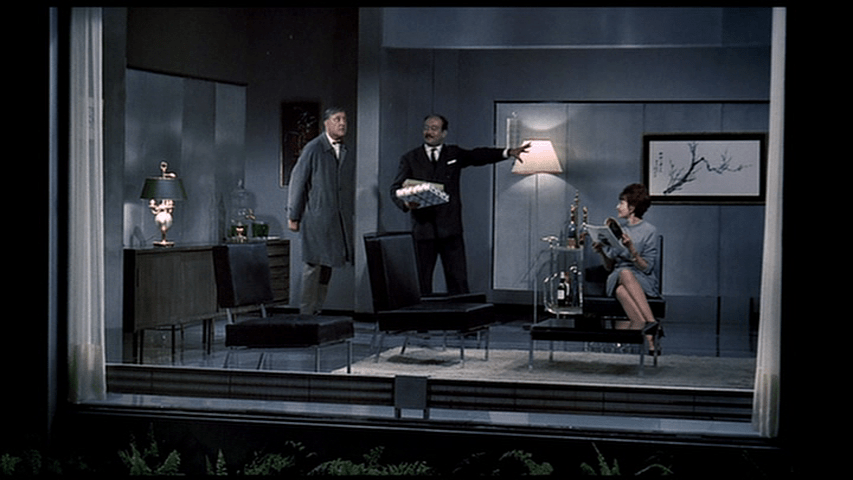

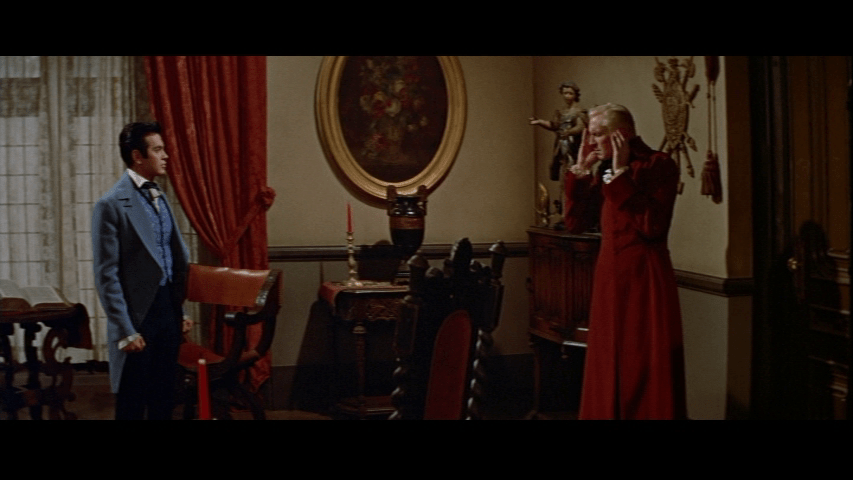

And with that we’re off and running! Foster’s lighter doesn’t work because it isn’t supposed to: “that’s how I meet so many nice people,” she informs Dugan. It’s a toss-up for me whether the *very* best thing about Black Sheep is the dialogue by director Allan Dwan (who wrote the story that the movie is based on) and screenwriter Allen Rivkin or the chemistry between its stars, who David Cairns brilliantly describes as “so delightful together you long for a whole season of Thin Man type romps for them to connive through (as he says, “sometimes film history just misses a trick”) although these things are of course related. The snappy one-liners come fast and furious right from the start: when Foster asks if she can buy Dugan a drink, his reply is “I don’t know, can you?” A few beaters later she labels them “two good mixers with no ingredients.” Then a bit further on after the two sneak upstairs to “see how the rich people live,” Dugan condenses a whole lifetime of back story into just a handful of sentences. “There are two things that always floor me,” he tells Foster, “horses and dames. One keeps me broke, the other crazy, and you can’t depend on either of them.” When she quips, “don’t tell me a horse jilted you!” he replies in kind: “yes, and a girl kicked me.”

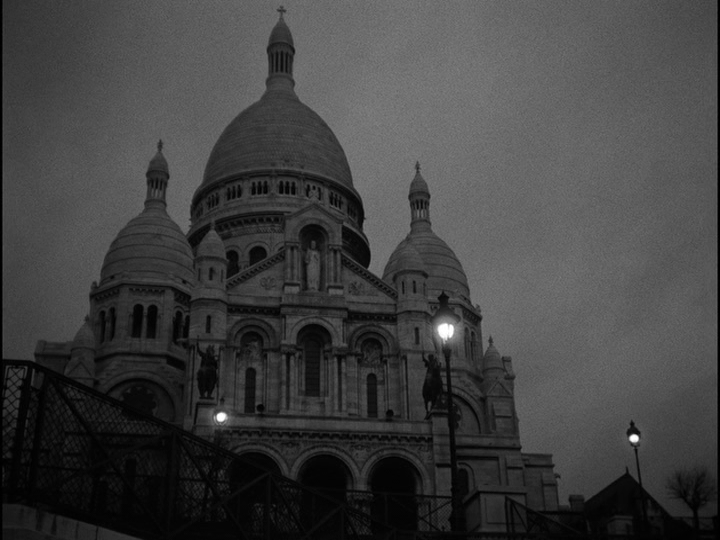

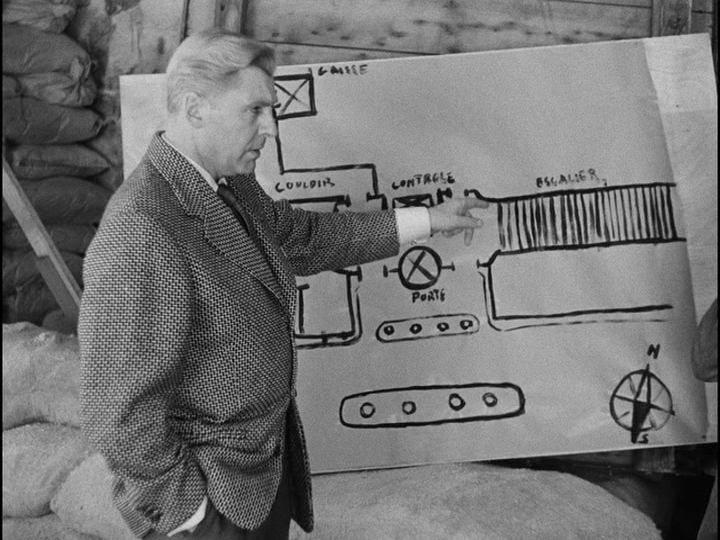

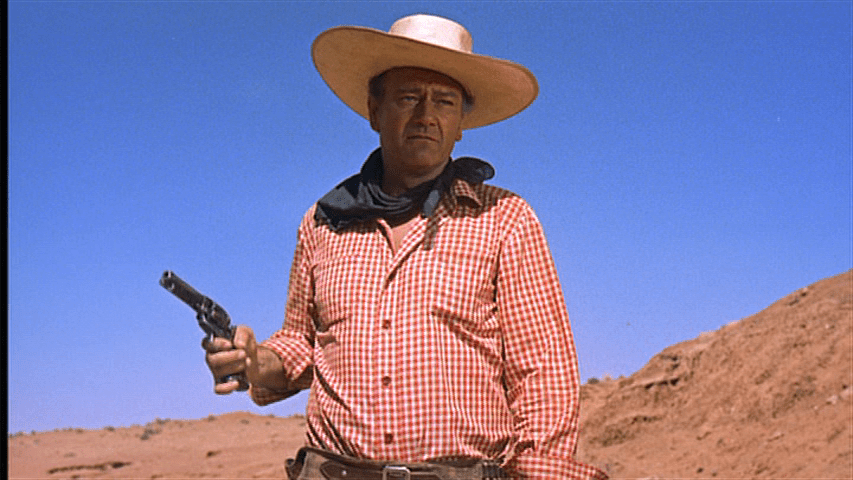

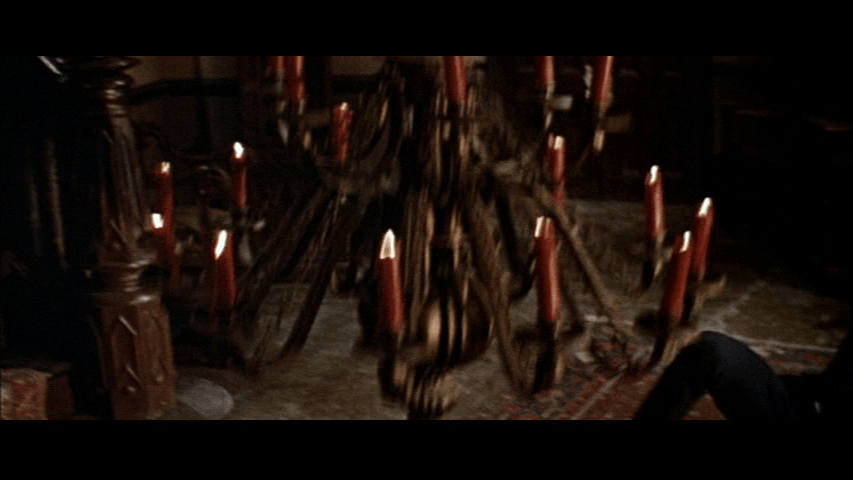

But then he adds: “that was twenty years ago. Forget it.” Speaking of coin flips, in addition to sharing a profession in common with the main character of last month’s Drink & a Movie selection Bob le Flambeur, Dugan similarly uses them as an external signifier of his deference to the Fates:

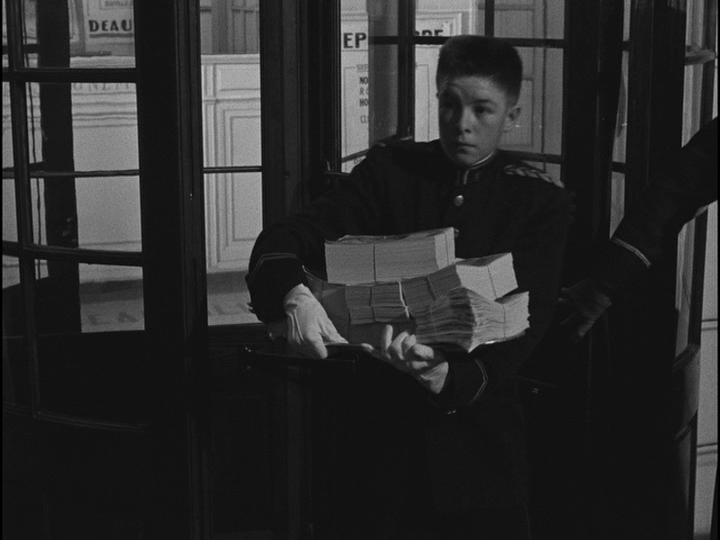

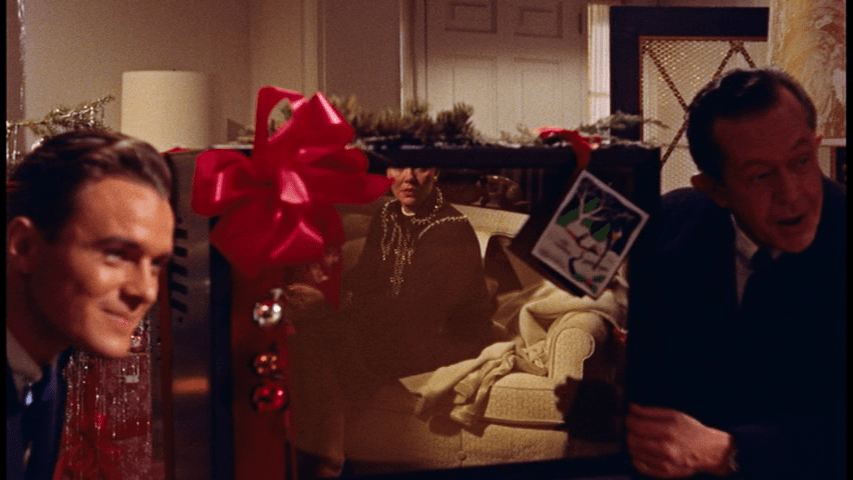

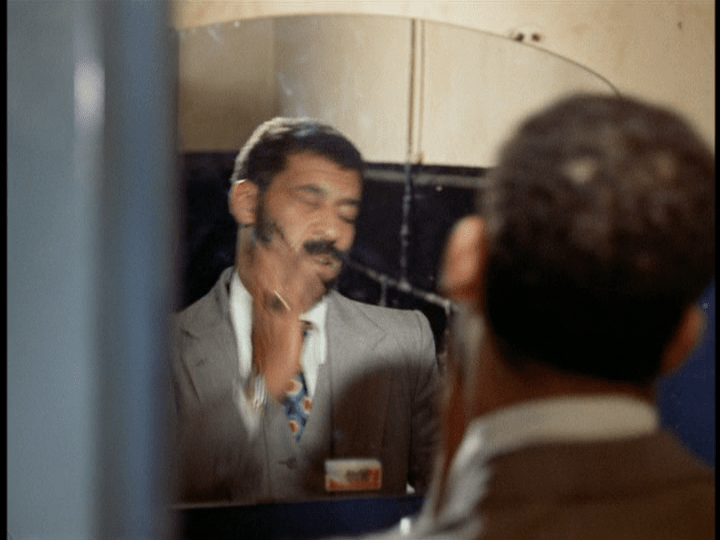

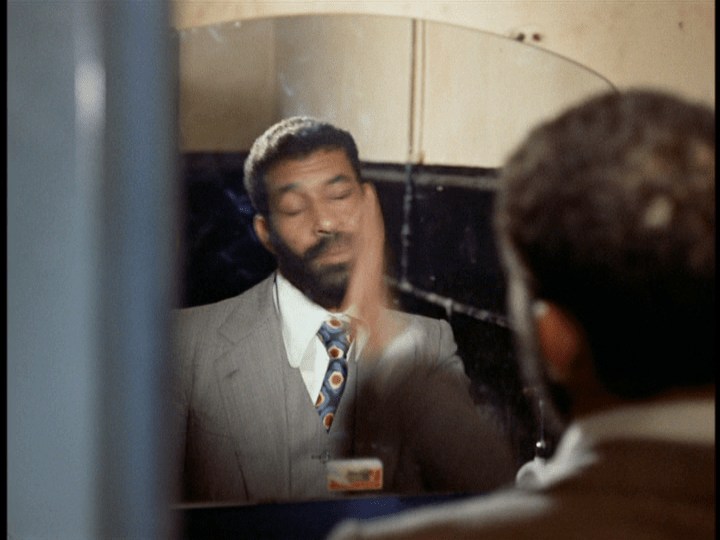

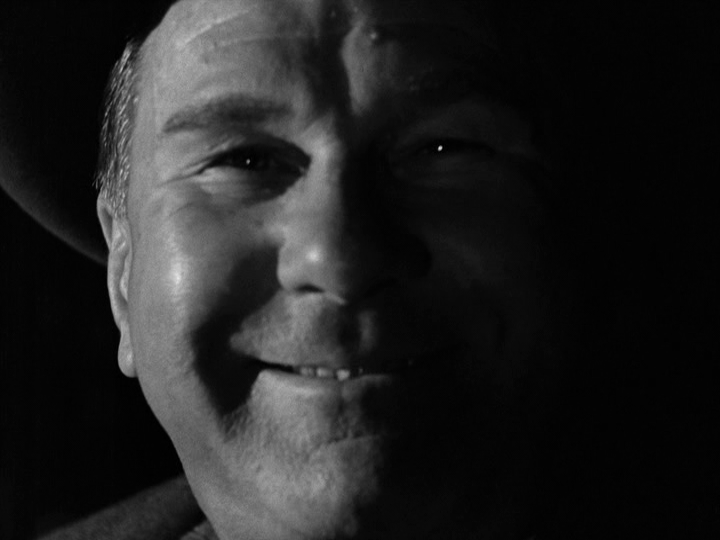

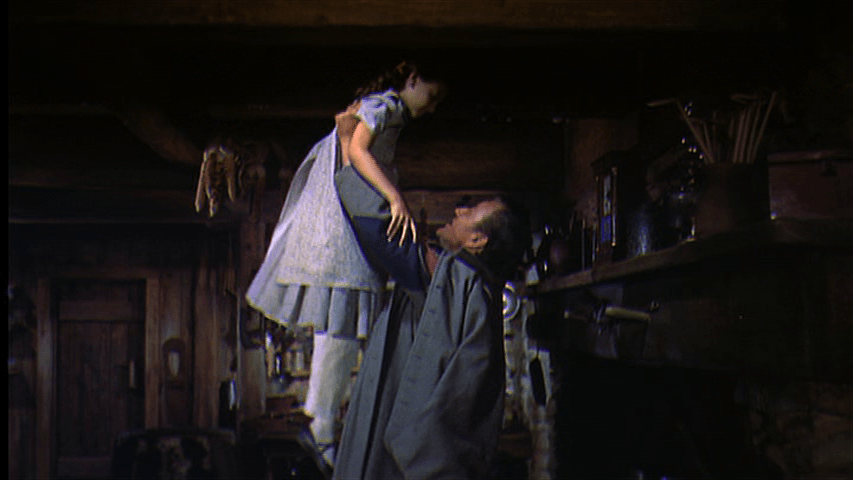

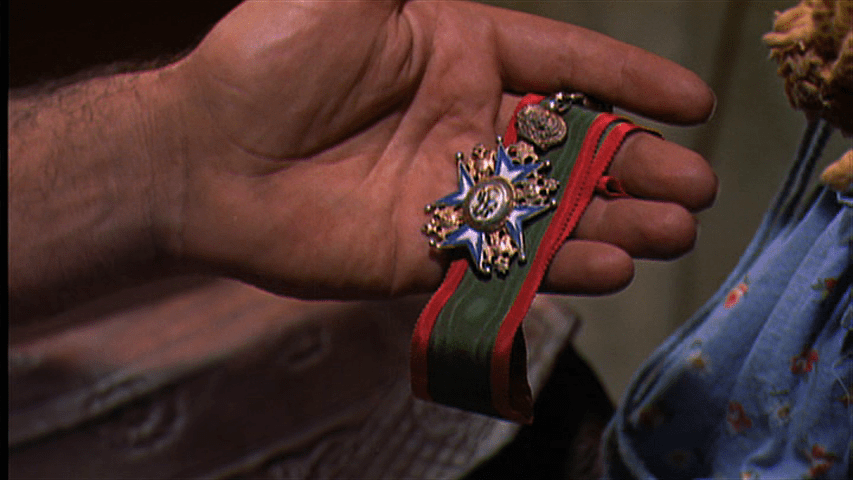

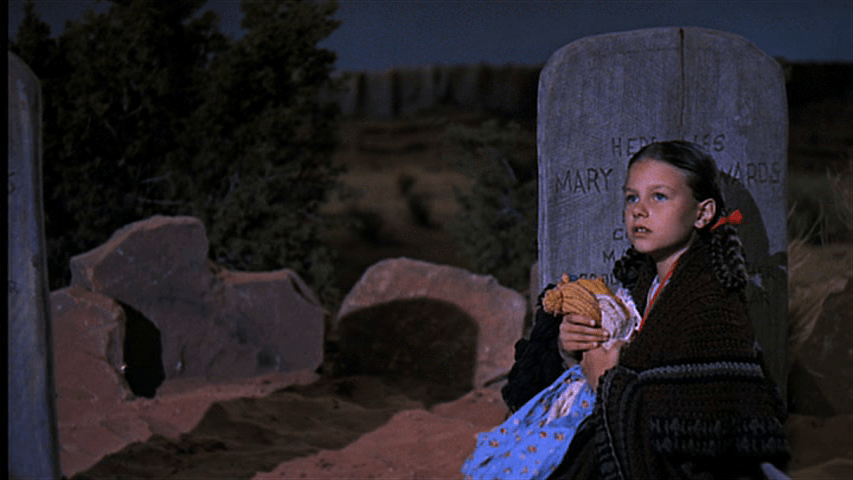

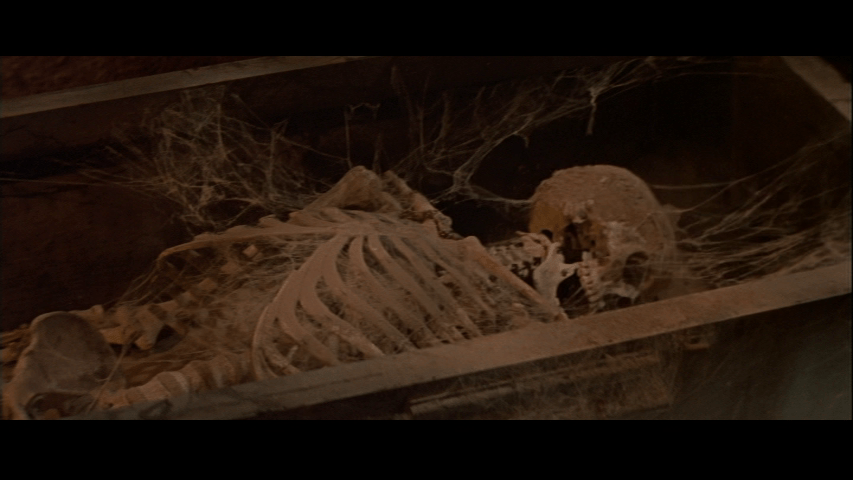

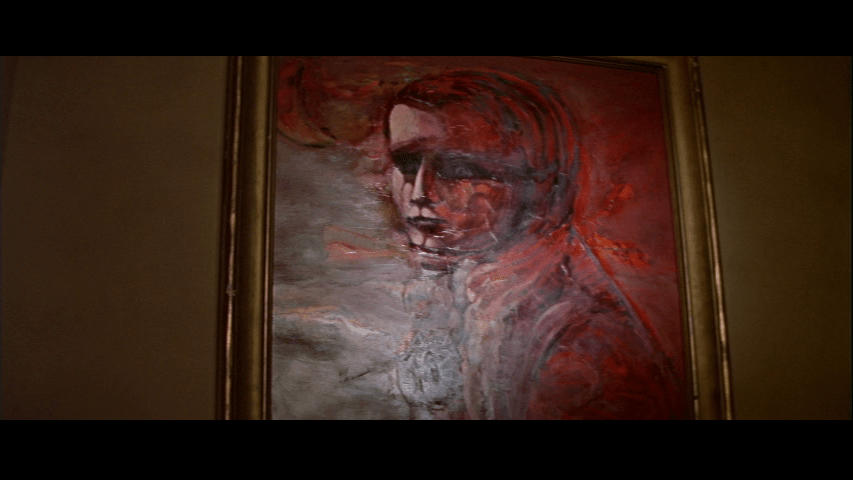

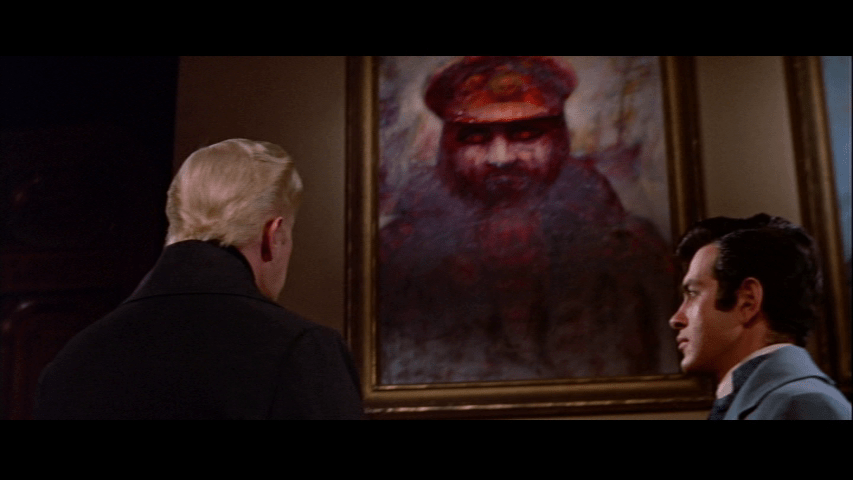

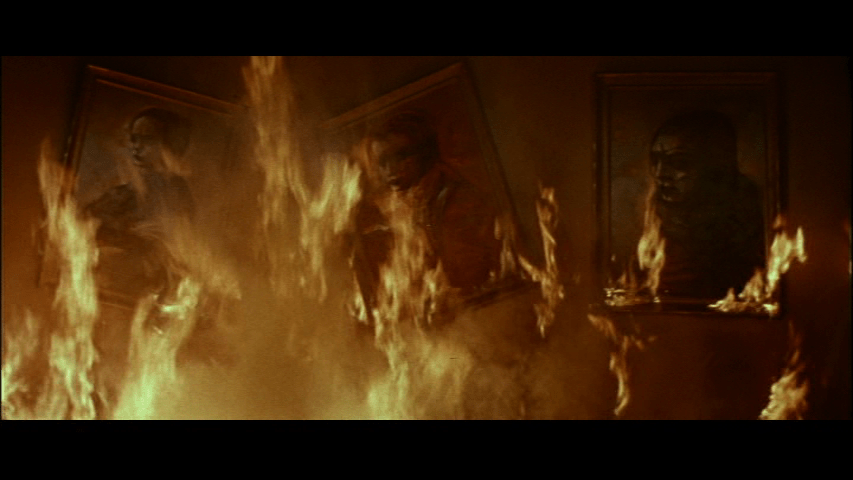

“Dugan and Foster stay in business,” he says after this one, referring to the partnership they have entered into to help a young man named Fred Curtis (Tom Brown) they observed getting fleeced in poker during their upper deck sojourn who also, as it happens, turns out to be Dugan’s son. This fact is revealed in a moment that Matt Strohl describes as “an emotional bolt of lightning in the middle of the film” which occurs after Dugan has helped Curtis win back some of the money he lost to Eugene Pallette’s and Jed Prouty’s buffoonish oil tycoons Colonel Upton Calhoun Belcher and Orville Schmelling by posing as his friend, but only at the expense of his own profits when he is forced to accept the checks Curtis wrote them as payment or risk giving up the ruse. He’s right in the middle of getting tough with Curtis (“I’ve got $1800 coming from you and I want it–in cash”) when suddenly he spots a set of framed photos:

“What’s the matter?” Curtis asks him after he notices the older man’s reaction:

“Oh, nothing, nothing–I probably had too much to drink or something,” Dugan stammers. He gives no further explanation, but immediately changes his tune regarding repayment. “Where’s that note for those rubber checks?” he asks, then looks on with what my daughter Lucy would call a “thin smile” while Curtis writes it:

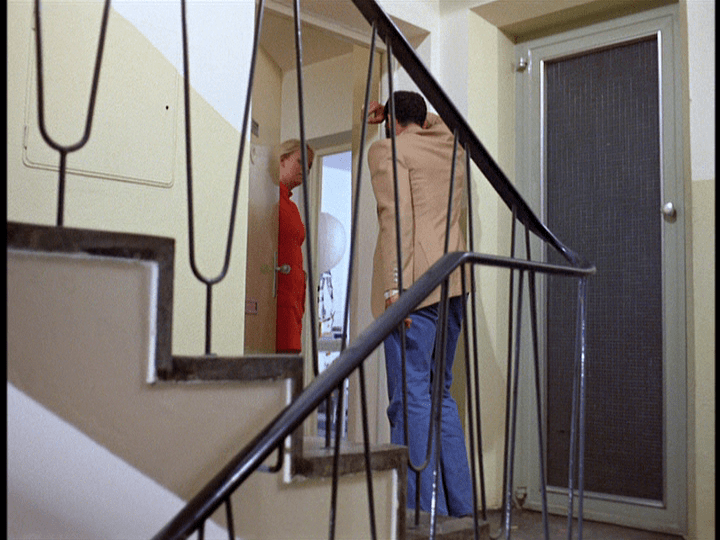

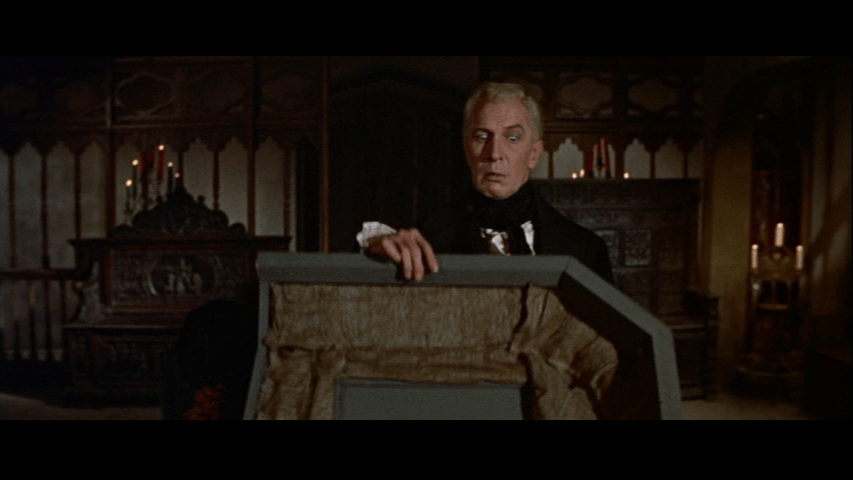

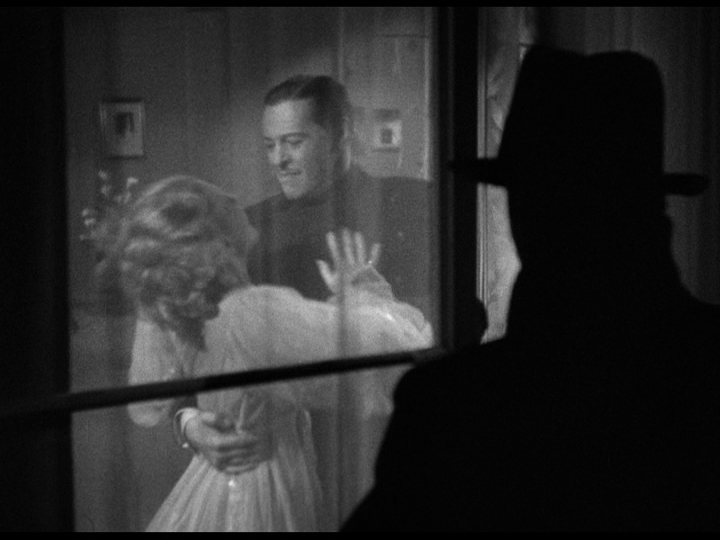

As Strohl notes, although Dugan never reveals his discovery to Curtis even through the end of the film, “that one reaction scene reverberates and lends weight to everything that follows,” including what I think must be the romantic non-kiss in the history of cinema. It takes place about halfway through a 30-second-long shot that begins right after the coin flip depicted above when Dugan notices Foster’s hand on the lapel of his bathrobe:

They put their arms around each other and lean in, but suddenly he pulls back:

It’s just for a second and they lean in again, but the result is the same:

Foster is already smiling as he lets out a perplexed sigh and is laughing by the time he calls for the steward to “take this lady out of here”:

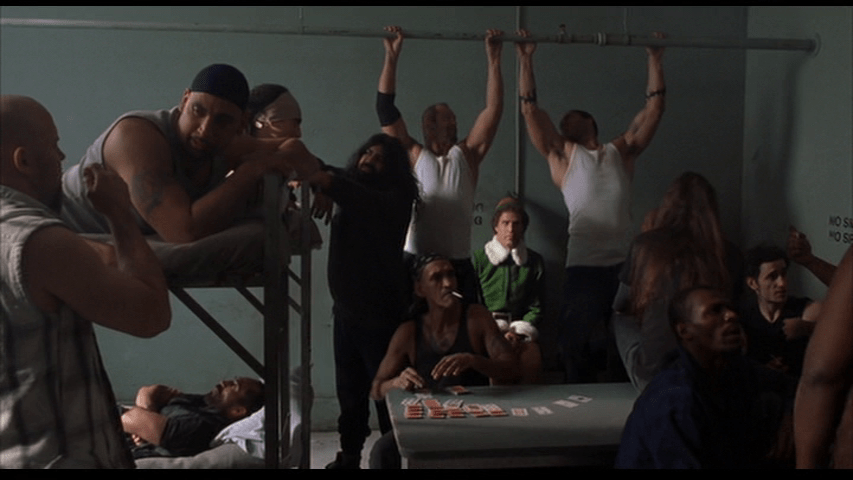

Destiny can bring lovers together but in my experience the key to a happy marriage is that you have to really like each other! Dugan is clearly wondering what the heck happened to him and there’s work still to be done, so the wedding bells will have to wait, but these two clearly have a future together and he’s earned it. And that brings us right back to where we started! The steward appears in this scene because Dugan is supposedly under lock and key, and as Lombardi notes “restriction of movement is a severe violation for a Dwan character and film,” but Dugan “uses his room arrest to serve his ends.” In other words, all those attempts to put Dugan in his place ultimately fail, which is another connection between him and Bob Montagné: they both remain true to themselves no matter how down and out they find themselves and are eventually rewarded. Which now makes three “exceptions to the rule” I wrote about in my February Drink & a Movie post about The Young Girls of Rochefort, suggesting that it’s time to update my notion that “the human experience of trying to become a better person” is a theme of this series. After all, resisting the temptation to change more than you need to can itself be a challenge. Which, come to think of it, is the secret to the Chapuline’s success, too, isn’t it? Toby Maloney elevated the grasshopper by tweaking its proportions just a bit and adding one single ingredient. Or, to reframe this in terms that Dugan and Bob (and Kenny Rogers) would appreciate, sometimes the highest form of wisdom is knowing how to quite when you’re ahead.

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka my loving wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.