I like spring peas, ramps, and fiddlehead ferns as much as the next fellow, but the seasonal ingredient I get most excited about during this time of year is rhubarb because it’s typically the first edible plant we’re able to harvest from our own yard. My favorite thing to use it in is pie, but it also makes an excellent shrub, and a couple of years ago I discovered that it can be transformed into a delicious syrup as well courtesy this drink recipe by Charlotte Voisey. Throw in the facts that, a) this cocktail is a great showcase for an excellent local spirit, 1911 Honeycrisp Vodka, and, b) it lends itself to garnishing with apple blossoms during the one week each year when they’re in flower, and you have an absolutely perfect beverage for upstate New York during the month of May! Here’s how we make it:

1 1/2 ozs. Apple vodka (1911)

3/4 oz. Rhubarb syrup

3/4 oz. Lemon juice

1 Tbsp Rosemary leaves

Lightly muddle the rosemary with the other ingredients. Add ice and shake, then double strain into a chilled glass and garnish with an apple blossom if you have one, an apple fan if you don’t and you’re feeling ambitious, or just serve as-is.

We don’t currently have a juicer, so we use this rhubarb simple syrup recipe from The Kitchn. The one place where we deliberately part from Voisey is by lightly muddling the rosemary before shaking. This could just be an issue with my technique, but we don’t get enough of that flavor otherwise, and its complexity is absolutely essential. An apple fan is a fun garnish, but the blossom takes this to a whole new aromatic level–it’s spring in a glass!

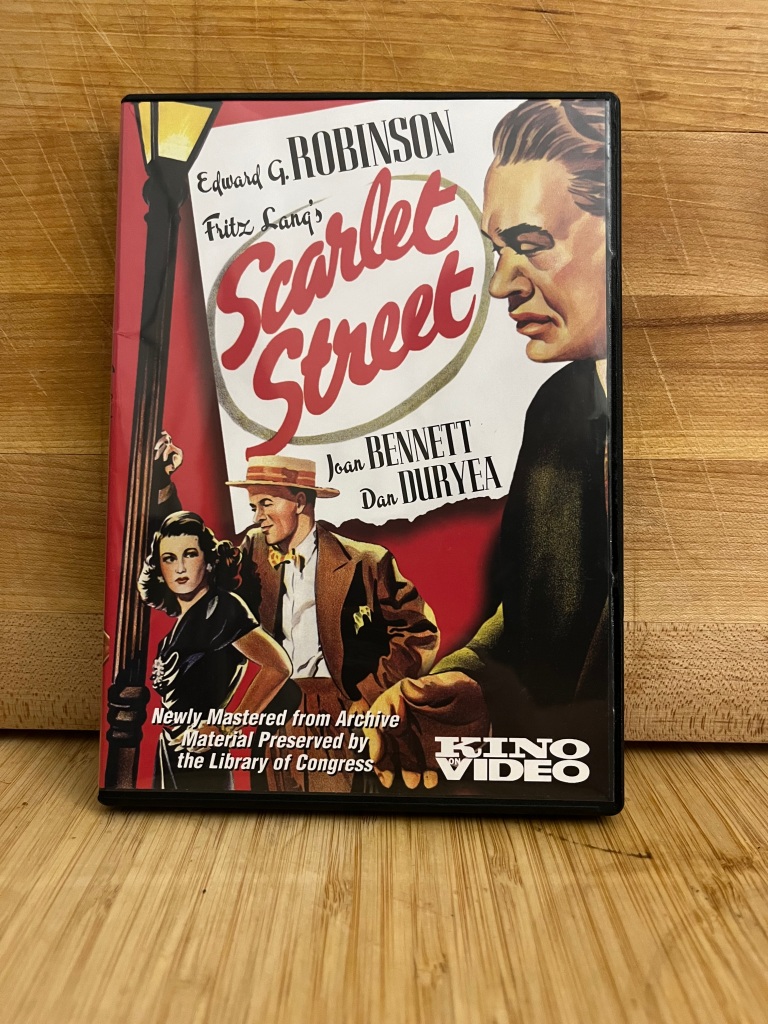

Between the rhubarb and the vodka, there was only one movie I was ever going to pair with this drink: Stalker. Here’s a picture of my Kino DVD release:

It has subsequently received a Criterion Collection Blu-ray/DVD release and can also be streamed on both The Criterion Channel and Max with a subscription or rented from a variety of other platforms.

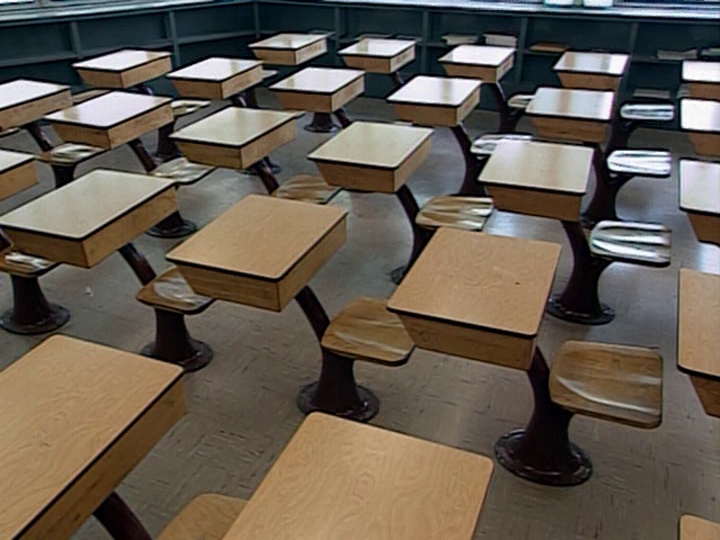

Stalker is adapted from Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s novel Roadside Picnic, but only loosely despite the fact that both authors are credited as screenwriters alongside director Andrei Tarkovsky. Both the movie and book begin with excerpts from interviews with a Nobel Prize winner. The latter one is substantially longer, identifies the speaker’s discipline as physics, and confirms that the Zone where the titular stalker (whose name in the book is Red Schuhart) plies his trade is indeed the site of an extraterrestrial visit. From there the differences multiply: the action of the book spans years as opposed to the single day or so of the movie; Red’s/Stalker’s daughter Monkey’s affliction is not an inability to walk, but rather non-human features which become more pronounced over time; there’s a major storyline about reanimated corpses; etc.

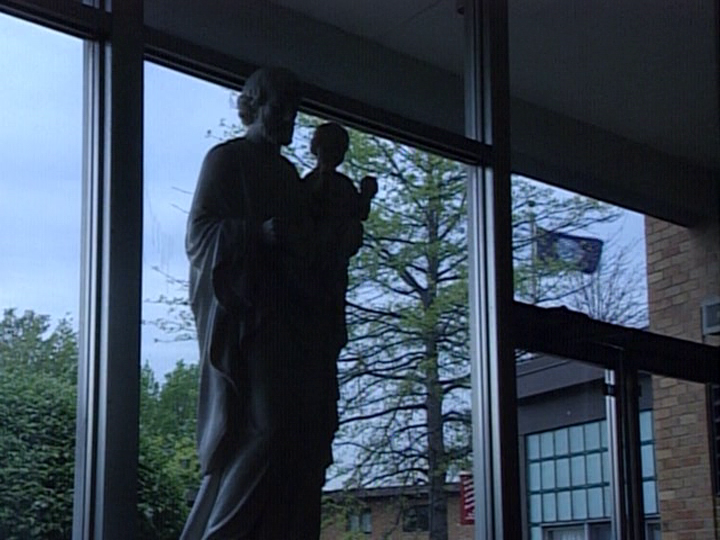

Perhaps the most relevant deviation is that in Roadside Picnic the Zone is littered with powerful (and in many cases dangerous) alien artifacts, which is how Red and his fellow stalkers make their living: they lead others on expeditions to recover them and sell some on the black market themselves. The movie, on the other hand, contains no corresponding futuristic props whatsoever. As Tarkovsky notes in Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema, “only the basic situation could be strictly called fantastic.” Instead, the profoundly otherworldly atmosphere of the Zone is created by what Maya Turovskaya calls “an infinitesimal dislocation of the everyday” in her book Tarkovsky: Cinema as Poetry. The example she cites is the phone which suddenly rings in a house which is completely cut off from the grid:

Another obvious one is these embers that Professor (the gentleman pictured above, played by Nikolay Grinko), Writer (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), and Stalker (Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy) encounter in a territory long deserted by people:

The effect is also achieved through subtler means like the strategic mismatches between sound and image that Andrea Truppin documents in a chapter in Rick Altman’s book Sound Theory, Sound Practice. As Stalker and his companions approach the remains of a military vehicle, for instance, the way the camera tracks forward, sound of footsteps, and additional touches like “the movement of successive tufts of grass at the bottom of the frame as if the feet of the character were crushing them” all imply a point-of-view shot:

However, as the camera continues its progress the three characters whose perspective we presumed it embodied appear on screen, negating that possibility:

In their book The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Vida T. Johnson and Graham Petrie note that “in a good print, the arrival at the Zone becomes genuinely magical, the grass a pulsating green that contrasts with the shabbiness and dinginess (yet, in a good print, intensely tactile detail) of the preceding sepia images”:

And to finish with the writer who got us started, Maya Turovskaya poetically describes the surprise appearance of a black dog as having “a hint of warning, like a distant echo of some half-forgotten legend” about it:

Stalker shares its technique of creating a science fiction universe out of images culled from the present with the 1965 film Alphaville, which also has a similar thesis. In Sculpting in Time, Tarkovsky says that in the former he makes “some sort of complete statement: namely that human love alone is–miraculously–proof against the blunt assertion that there is no hope for the world. This is our common, and incontrovertibly positive possession. Although we no longer know how to love. . . . ” Compare this to the final lines between Natacha von Braun (Anna Karina) and Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine) in the latter:

NATACHA: You’re looking at me oddly. It’s as if you’re waiting for me to say something. I don’t know what to say. I don’t know the words. I was never taught them. Help me.

LEMMY: I can’t, princess. You have to get there by yourself to be saved. If you can’t, then you’re as lost as the dead souls of Alphaville.

NATACHA: I . . . love . . . you. I love you.

But where that film’s director Jean-Luc Godard seems to be making the (unusually for him) simple argument that the seeds of a dystopian future have not only already been planted, but are in fact beginning to bear fruit, Tarkovsky is up to something different when he parades objects like this across the screen:

Or when he employs classical music in Stalker‘s incredible ending, which follows an ersatz miracle–a medium shot appears to show Monkey (Natalya Abramova) walking!

Until the camera pulls back to reveal that her father is carrying her on his shoulders across a landscape overlooked by cooling towers:

A few scenes later Monkey sits at a table reading a book:

As the camera slowly and unsteadily retreats from her, revealing a trio of glasses at the bottom right corner of the frame, we hear a lone train whistle and an isolated synthesizer from electronic music pioneer Eduard Artemyev’s score. Seeds from dandelions or some other plant float across the screen and a voice begins to read a poem by Fyodor Tyutchev which Björk later turned into the song “The Dull Flame of Desire”:

The train whistle sounds again and Monkey tilts her head to one side. Suddenly, the dog which accompanied Stalker back from the Zone whines and one of the glasses begins to move:

As it comes to rest at the corner of the table, a second glass, or rather a jar containing an egg shell, begins to inch forward in the same halting manner:

It stops a few moment later and the third glass begins to slide. Monkey rests her head on the table as it continues its journey all the way to the edge of the table, then over it:

As the glass lands with a thunk, the table starts to shake and the camera begins tracking toward Monkey:

We hear the sound of a train and fragments of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Fade to black. Tobias Pontara argues in Tarkovsky’s Sounding Cinema: Music and Meaning from Solaris to The Sacrifice that this is “a massive critique of modern history and civilization”:

In the sound of passing trains and in Beethoven’s music, we can hear a faint and fading echo of the restless striving of humanity as it tries to make sense of, conquer and colonize the universe, without as well as within. The scene makes it clear, however, that this grand project is a failure, and that what is ultimately of importance is something very different, something that will forever elude and outlast the signifying practices represented in the soundtrack.

His jumping-off point is a comment by Truppin that, “[i]f the train’s roar and its distorted music represent the destructive forces of Western civilization, the power of spirituality is represented by the small child, who calmly and gently moves the world, an embodiment of the Christian concept that ‘the meek shall inherit the earth.'”

The work of these scholars is some of my favorite writing on Stalker and they both provide ample support for their claims, but I don’t find their readings of this scene entirely convincing because Monkey’s telepathic powers have a different meaning for me than they do for them. I do agree with Pontara that “[t]he transfiguration in the last scene places the Stalker’s daughter firmly outside of civilization” and that “her relation to the sonic icons of modern civilization expresses in a radical way the possibility of overcoming and transcending the illusory ideals of that civilization.” What this reminds me of, though, is another classic of science fiction that the Strugatsky brothers surely must have been familiar with: Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, which also involves children who develop in an unexpected directions as a result of interference by visitors from the stars. That book ends with the offspring of our species literally destroying the earth as part of their merger with a cosmic intelligence called the Overmind. Tarkovsky asserts in Sculpting in Time that “[i]n the end everything can be reduced to the one simple element which is all a person can count upon in his existence: the capacity to love.” The Monkey of Roadside Picnic appears to be evolving beyond that capacity; Stalker ends with that same character displaying the same sort of telekinetic powers that Jennifer Anne Greggson has in Childhood’s End. These associations are too tenuous for me to insist upon them, but they prevent me from embracing the ending of the film as unambiguously optimistic.

Noel Vera makes an interesting observation in his Critic After Dark blog post about Stalker: the room in the Zone that the main characters seek out which supposedly grants anyone who enters it their heart’s secret desire has catfish swimming about in it:

“What might they wish for, and have any of their wishes been granted?” he muses. Perhaps we should be like Kent Brockman and welcome these fish as our new overlords. If the very best aspects of humanity are inextricable from the absolute worst, it might be time to give someone else a crack at running the planet–why not them?

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka my loving wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.