I knew from the moment my Drink & a Movie series was born that I would eventually feature the Last Word, and by the time the credits rolled on my first viewing of Pyaasa last year there was no doubt which movie I would pair it with. I originally slotted this post for late fall with a vague thought that I could mention actor-director Guru Dutt’s facial hair in the context of Movember or because of National Novel Writing Month, even though the character he plays is a poet. Sadly, the recent passing of Seattle bartender Murray Stenson, who is credited with rescuing the Last Word from obscurity, made my timing even more appropriate.

The main things you need to know about this concoction in 2023 are that: 1) it’s not for everyone, as I learned the hard way about ten years ago when we ordered a round for our table at a conference and one by one they all got passed over to me as each of my colleagues decided they weren’t a fan, which eventually resulted in me singing karaoke in front of co-workers for the first and only time in my life; and 2) if you are a fan of Green Chartreuse, this is (along with drizzling it over the best chocolate ice cream you can find) one of the few uses for the bottle you hoarded away a few months ago that is superior to just drinking the stuff straight as a digestif. Here’s how to make it:

3/4 oz. Gin (Broker’s)

3/4 oz. Maraschino liqueur

3/4 oz. Green Chartreuse

3/4 oz. Lime juice

Shake all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled coupe glass.

Most Last Word recipes note that it was invented at the Detroit Athletic Club prior to Prohibition, included in Ted Saucier’s 1951 book Bottoms Up, then rediscovered and popularized by Stenson 50-odd years later. The origins of its name deserve to be more well known, too. As described in Gary Regan’s book The Joy of Mixology, it was introduced to New York by famous vaudevillian Frank Fogarty, who Regan quotes as saying “you can kill the whole point of a gag by merely [using one] unnecessary word.” The Last Word is rather tart, but although adding a bit of simple syrup might make it more accessible, I don’t recommend it: the assertiveness of this cocktail is its best quality! Acid, spice from the gin, and herbs from the Chartreuse explode on the palate. With the latter clocking in at 110 ABV, you definitely should consider making it your final drink of the evening, though.

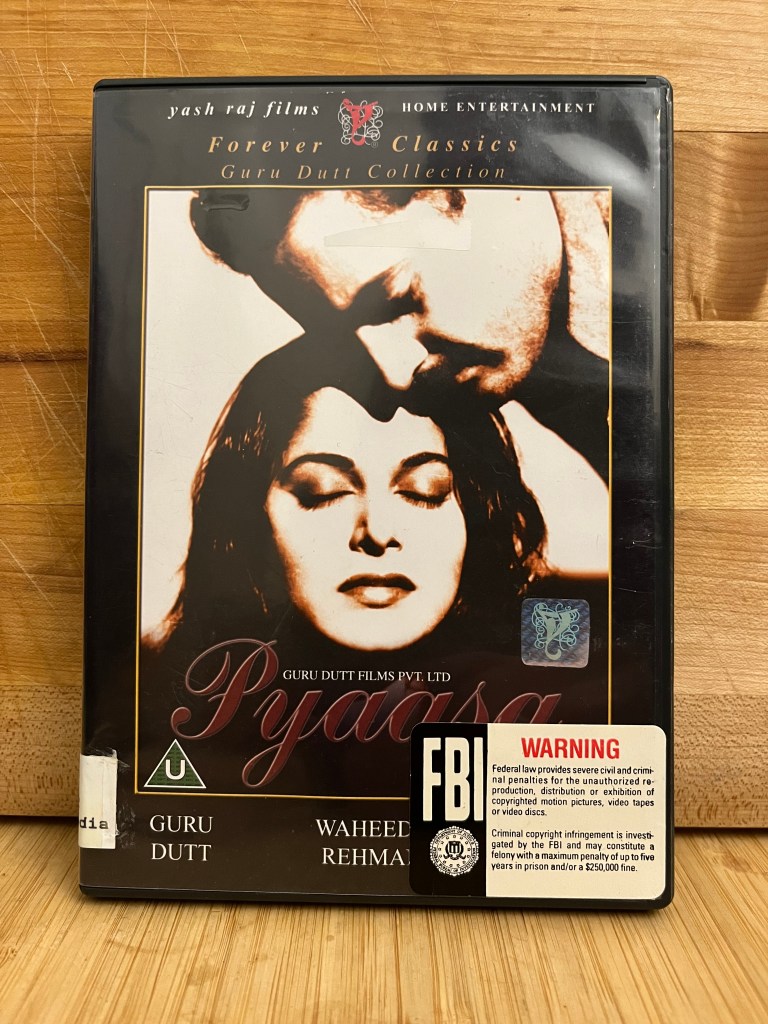

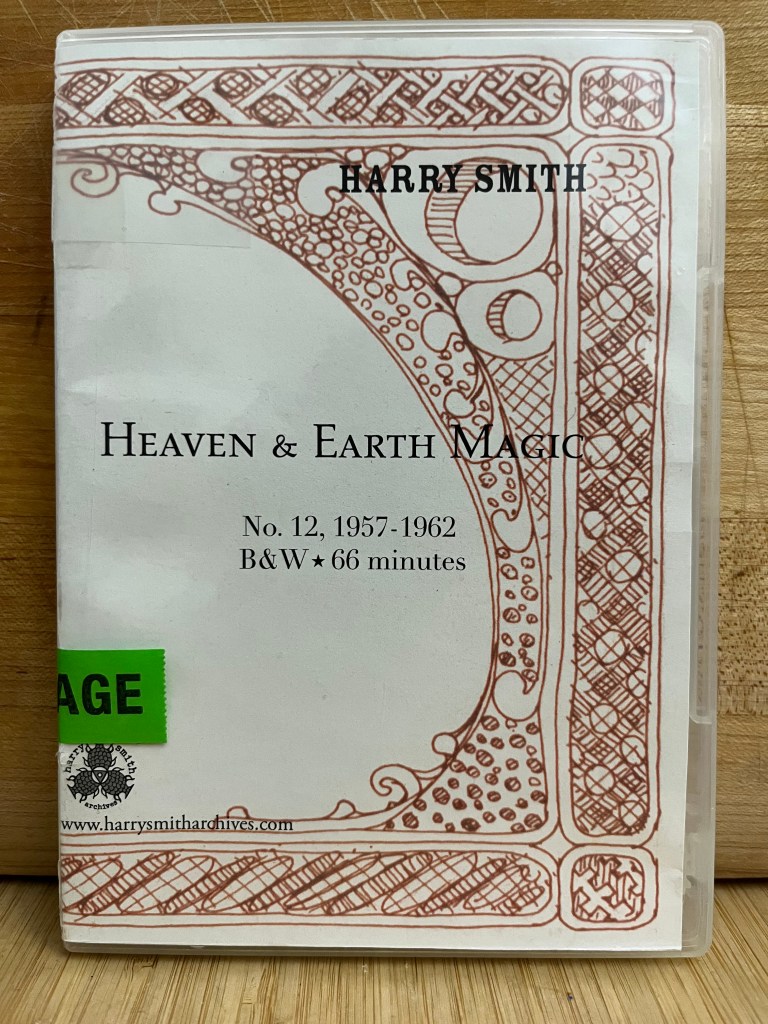

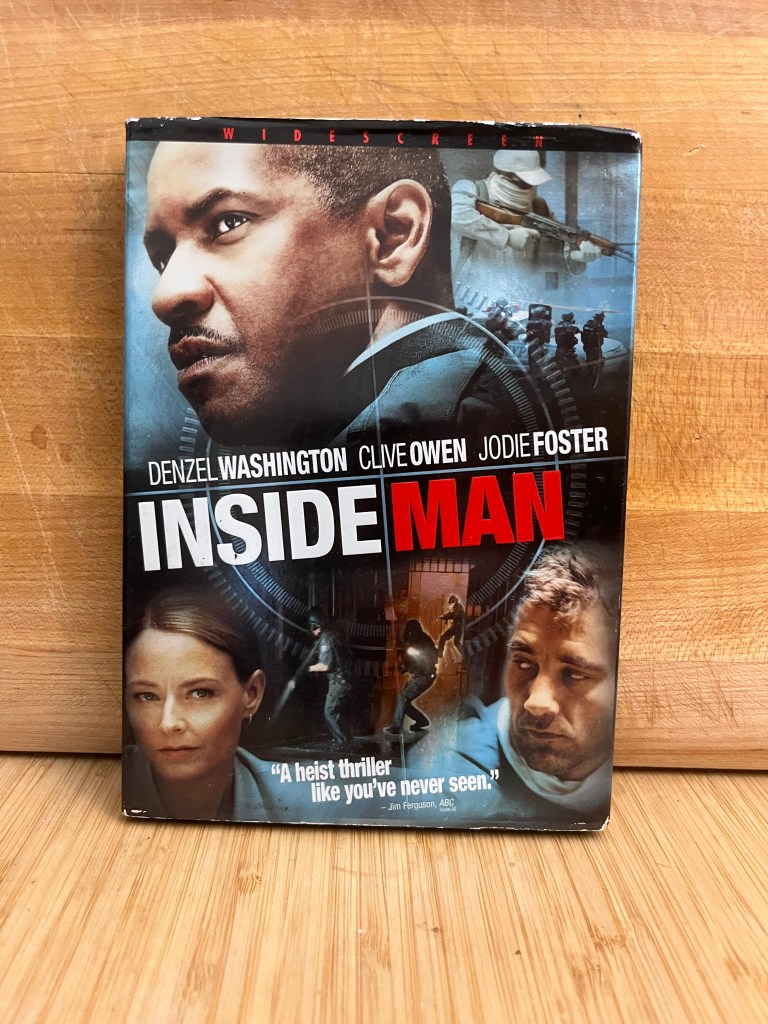

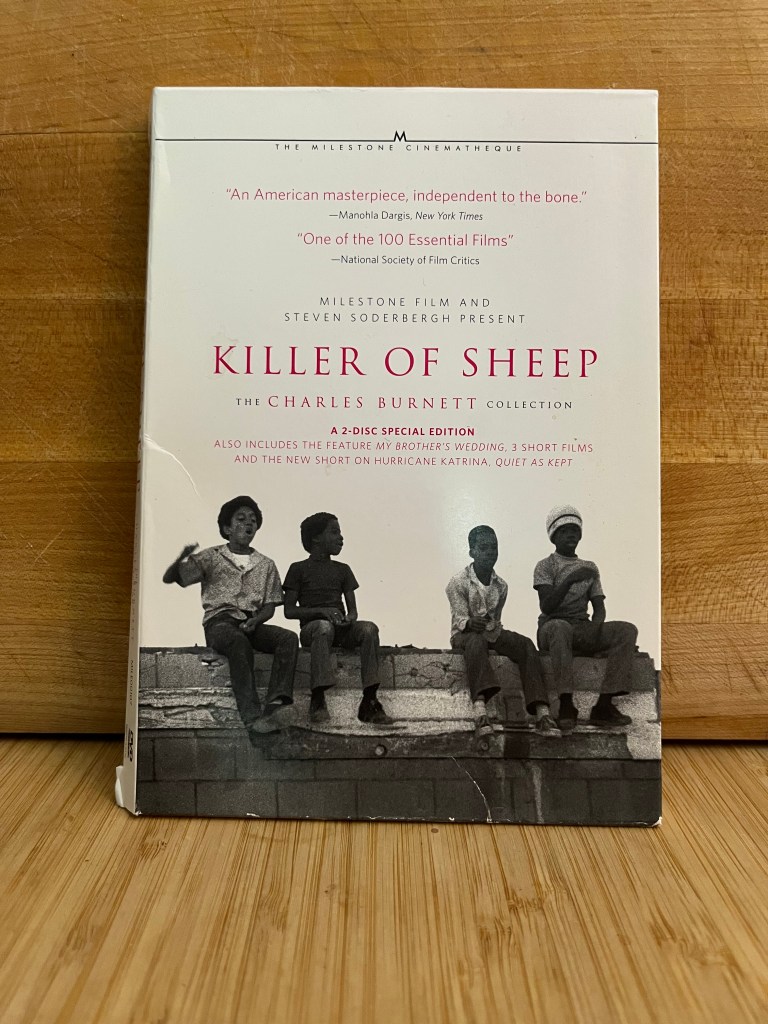

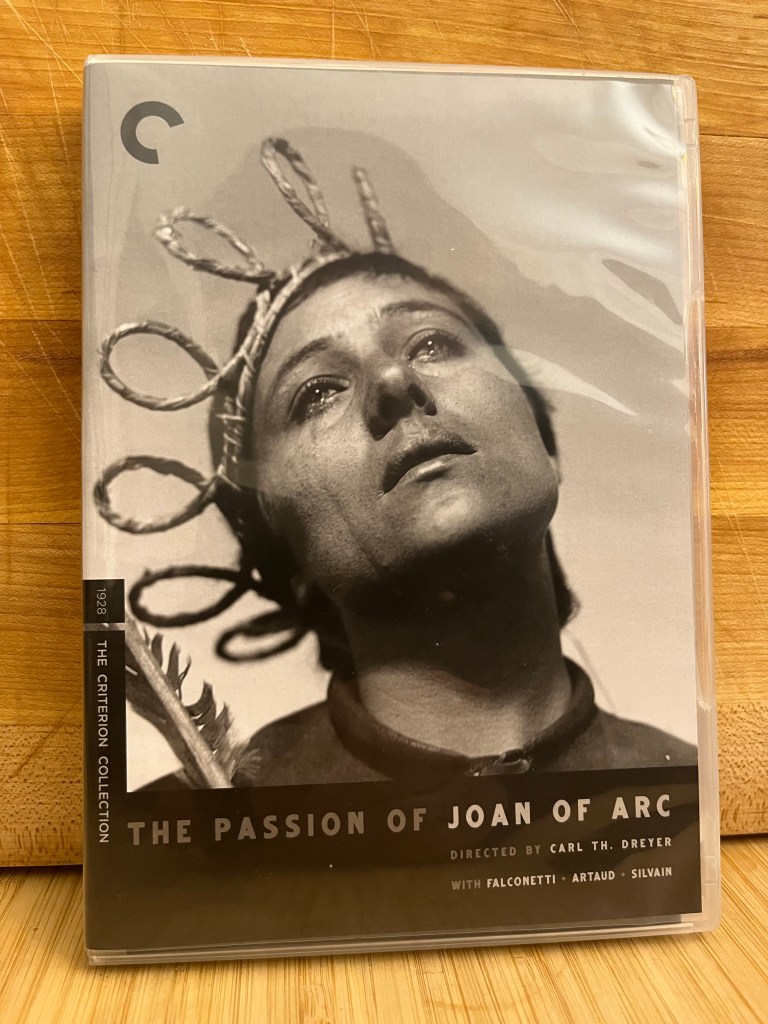

The screengrabs in this post come from a copy of the Yash Raj Films DVD release which I borrowed via interlibrary loan:

I actually own a DVD copy of the film released by Ultra Media, but it has a persistent watermark in the top left corner (yuck!) and I was thrilled to get my hands on the edition that DVDBeaver identified as being the best one available. It can also be streamed on Prime Video for a rental fee.

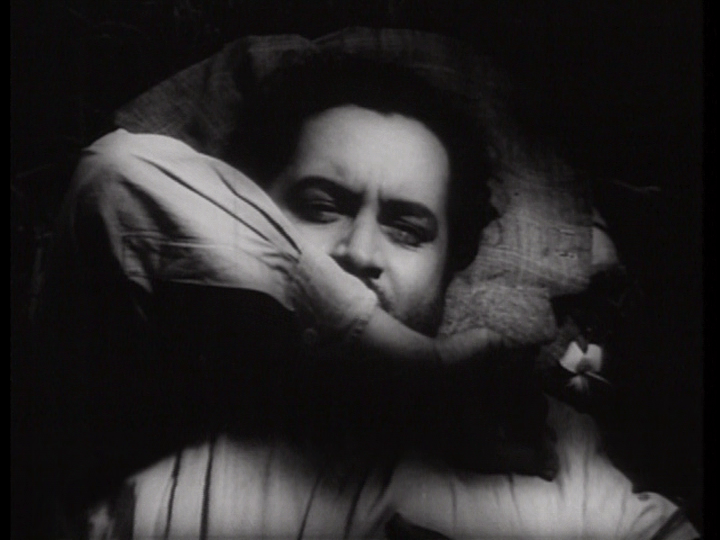

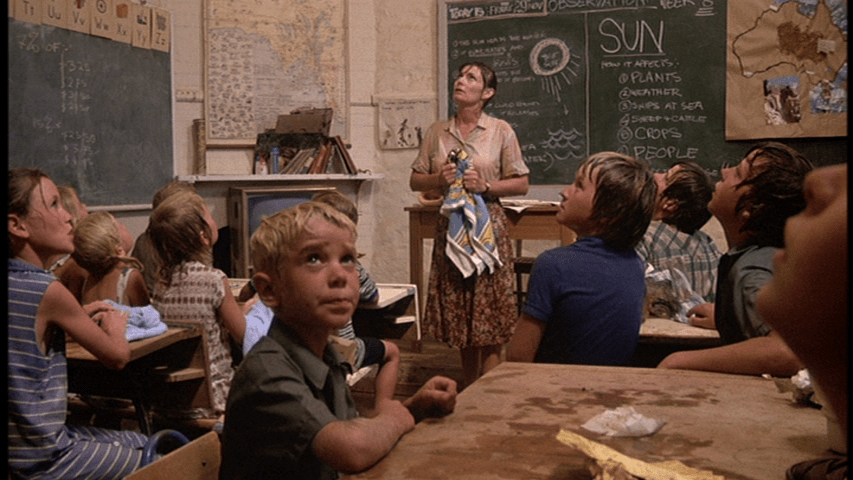

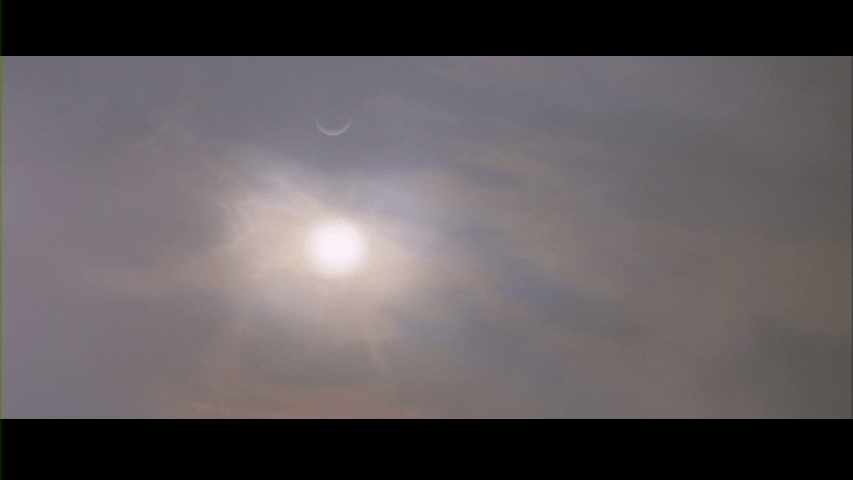

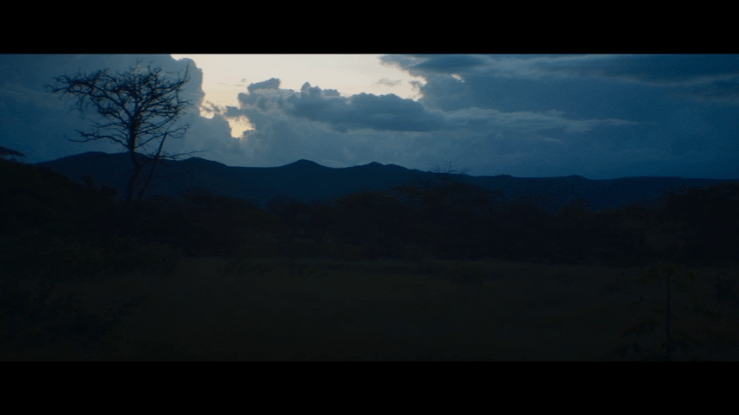

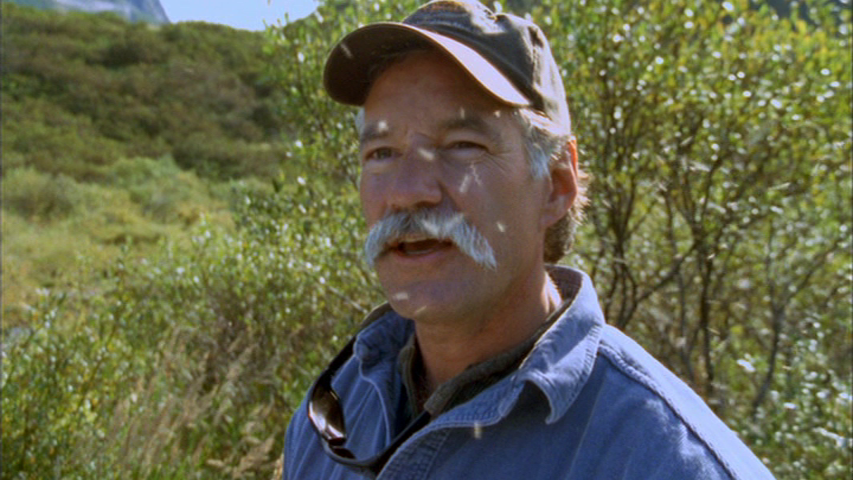

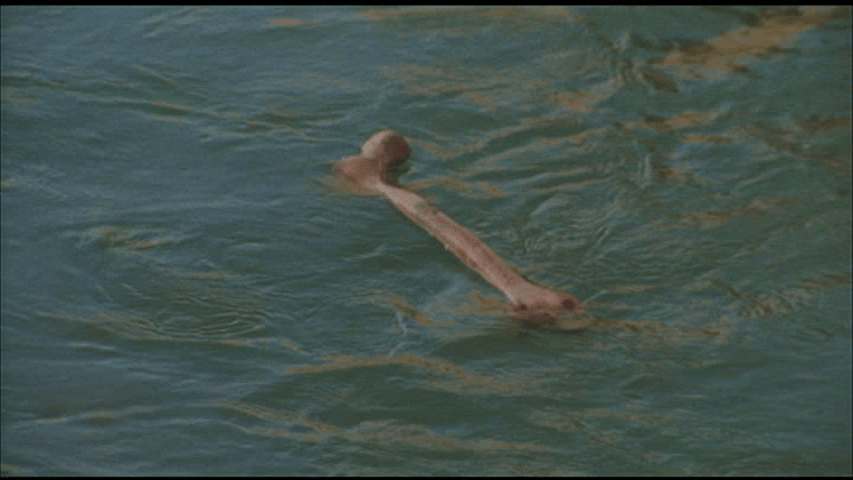

Pyaasa begins with falling blossoms waking Dutt’s Vijay up from a night spent sleeping rough in a park:

The beauty of nature moves him to compose a poem: “These smiling flowers/These fragrant gardens/This world filled with glorious colours/The nectar intoxicates the bees/What little have I to add to this splendor save a few tears, a few sighs.”

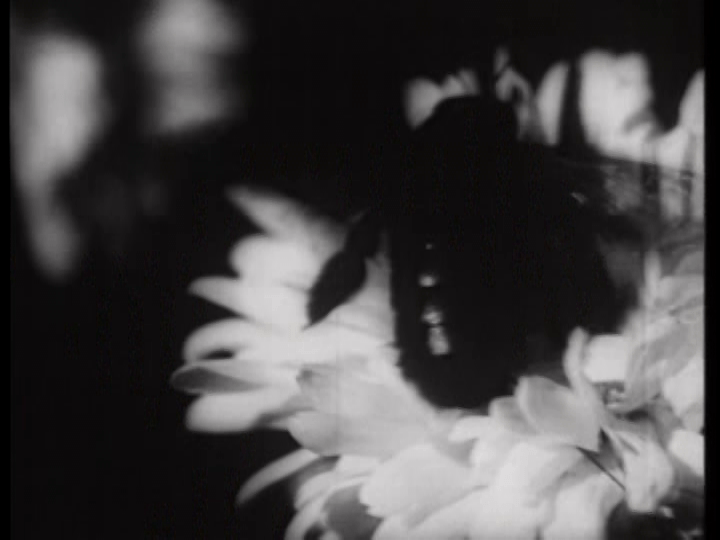

But then, as he watches, a bee lights on the grass, where it is trampled by one of his fellow Kolkatans:

This may be for me the best example of what I think scholar Corey Creekmur is writing about in his chapter on the film for editor Lalitha Gopalan’s book The Cinema of India when he says it “may well be the Hindi Citizen Kane (1941), a work whose audacious style, autobiographical resonance and lasting impact on filmmakers have exceeded its initial success.” The scene is a subliminally effective stage-setter on the first viewing. It struck me as perhaps a bit heavy-handed on the second. Beginning with the third, though, all sorts of interpretations start to open up: the bee is Guru Dutt! It is a worker bee! One bee alone may be helpless to oppose a shoe, but consider the swarm!

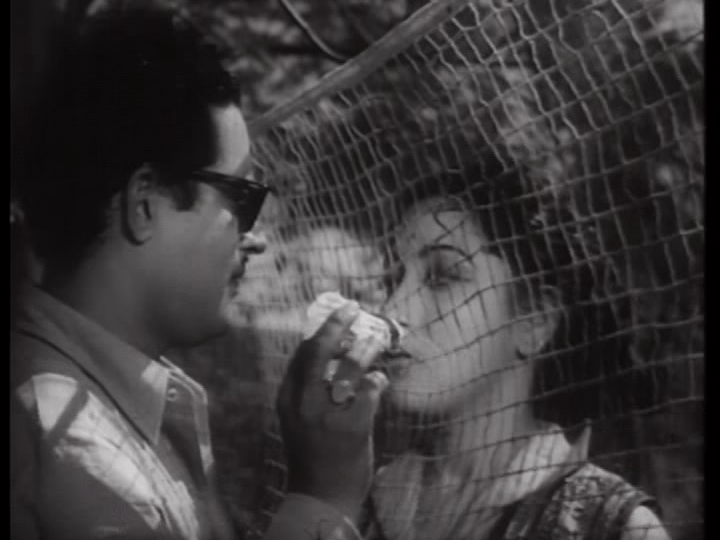

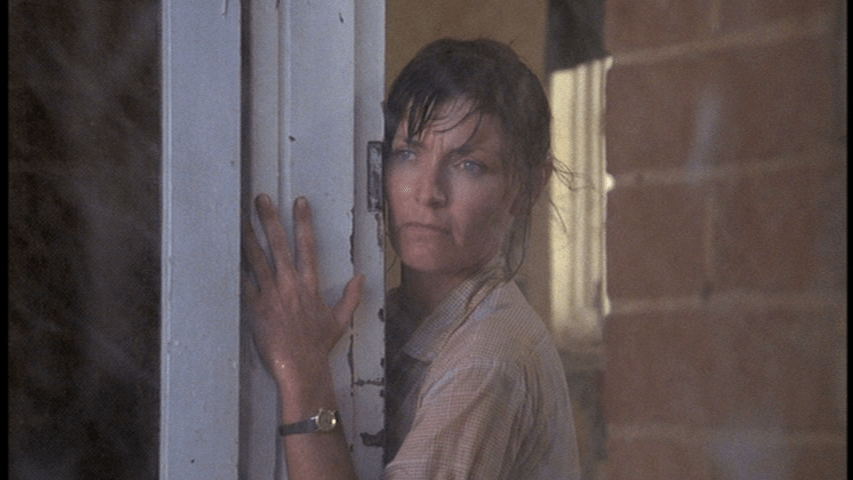

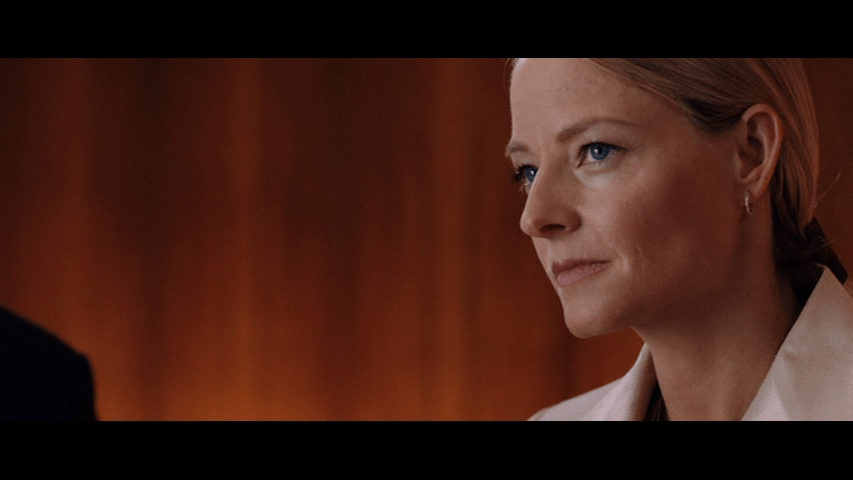

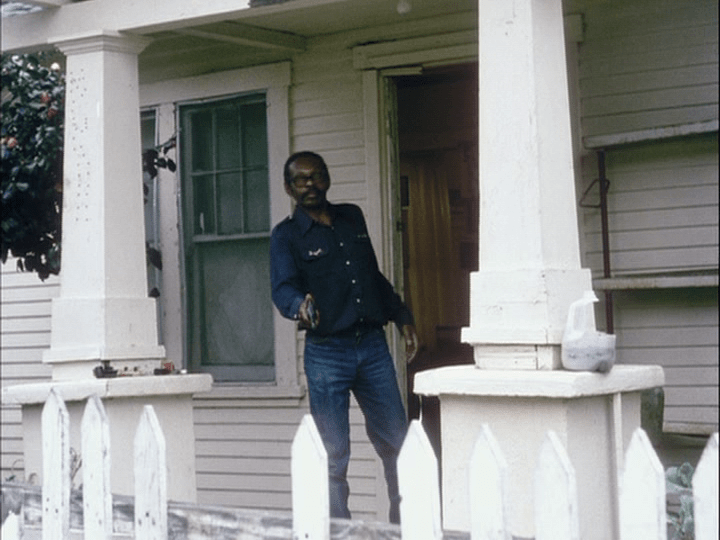

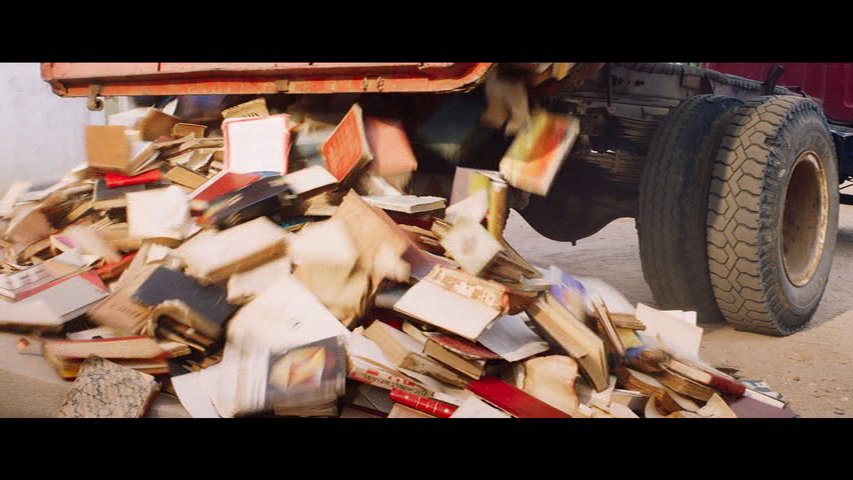

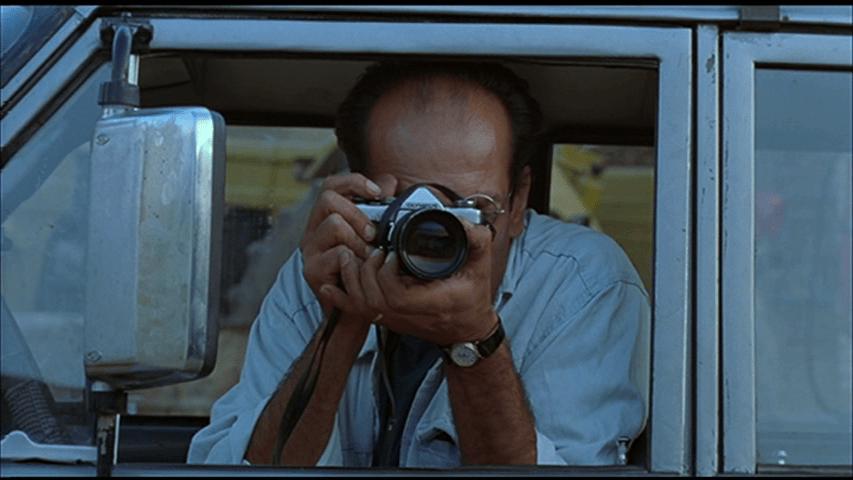

The story is fairly straightforward. Vijay can barely afford to feed himself because no one will buy his poems, except when his half-brothers sell them as wastepaper. Gulabo (Waheeda Rehman) is a prostitute who chances upon them and recognizes their worth. They meet cute when, thinking he’s a potential customer, she tries to seduce him with his own composition in a scene which uses columns and shadows well to hide and reveal her face:

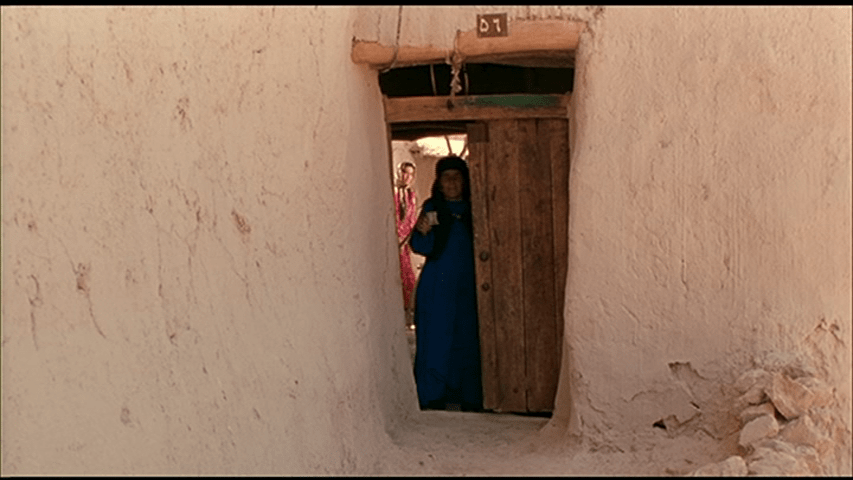

Vijay is initially oblivious to her affection both because he’s consumed with his work, and because his first love Meena (Mala Sinha) reenters his life in the following scene, which includes a flashback to the two of them in college:

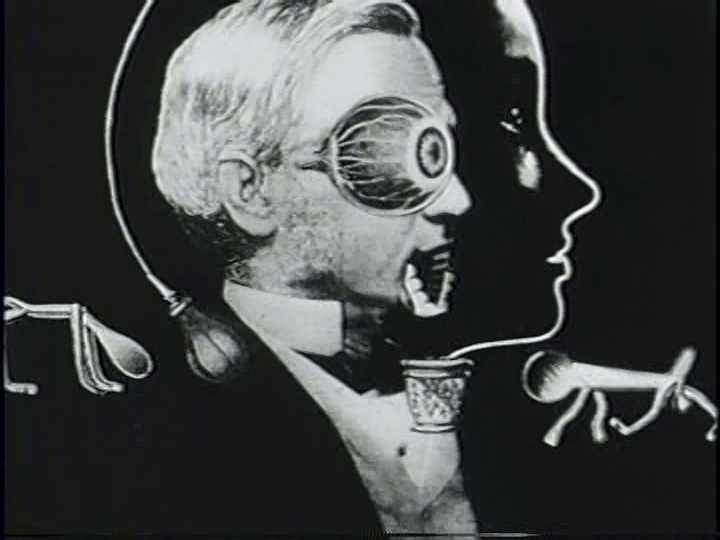

As scholar Carrie Messenger notes in a chapter on the film in editor Marlisa Santos’s book Verse, Voice, and Vision: Poetry and the Cinema, this is a reworking of the themes of Saratchandra Chattopadhyay’s novel Devdas with poetry taking the place of alcohol as an “addictive and destructive” force in the protagonist’s life. Messenger adds that the triangle of Meena/Vijay/Gulabo would have reminded many contemporary viewers of gossip that Dutt, Rehman, and playback singer Geeta Dutt constituted a real-life love triangle and that Pyaasa “features song sequences where the voice of Guru Dutt’s actual wife is channeled through the body of the lover, both through Gulabo and through Meena, a tension that disembodies the voice at the same time that it also creates the strange embodiment of an idealized creation, a Frankenstein, the best of both of these women as well as Geeta Dutt’s voice,” which is fascinating.

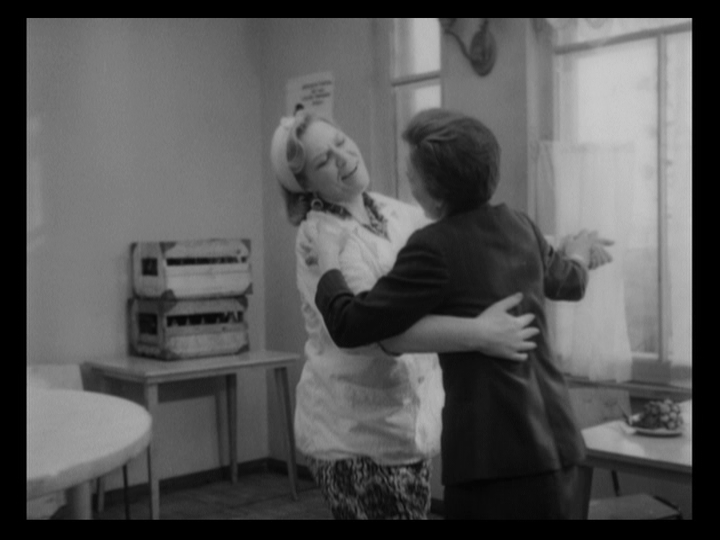

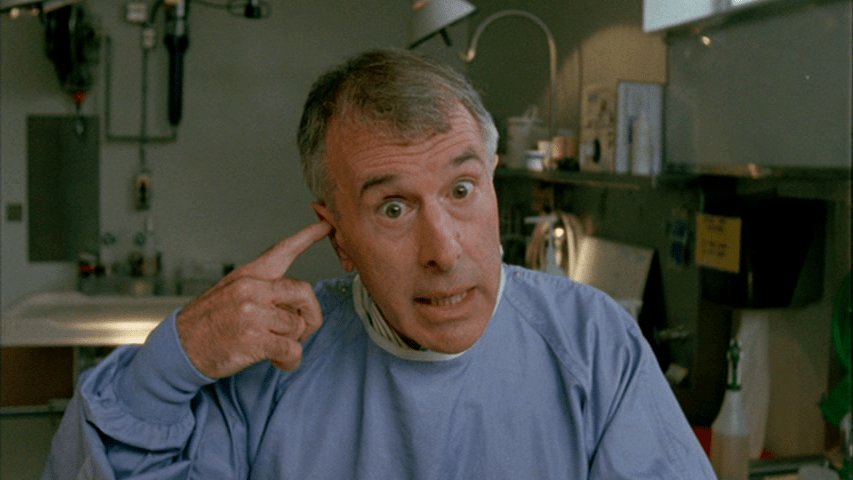

The songs are one of the best parts of the film. My favorite is probably “Sar Jo Tera Chakraye,” which is sung by Mohammed Rafi and set to a comic set piece featuring Johnny Walker, a member of my personal character actor hall of fame.

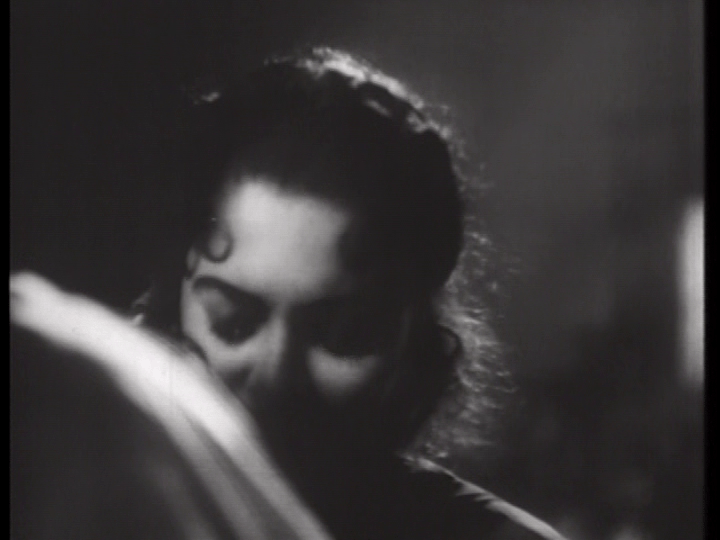

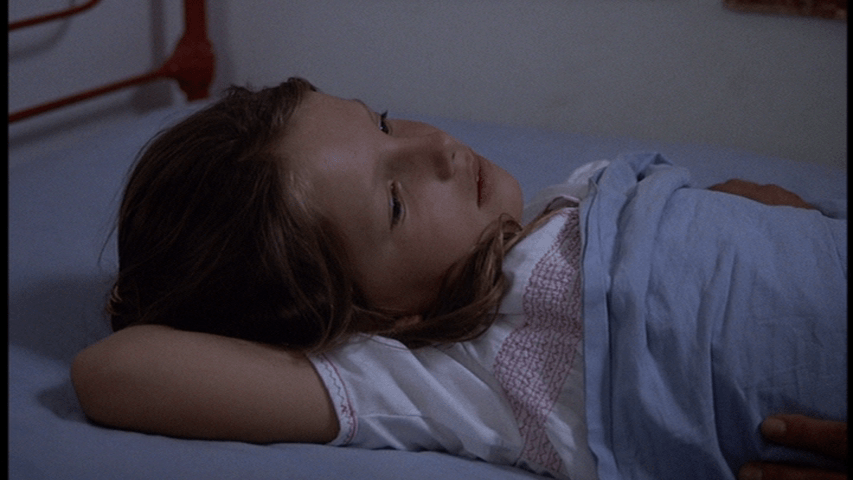

“Aaj Sajan Mohe Ang Laga Lo” features some first-rate unrequited longing, which I’m a total sucker for–Gulabo actually isn’t resting her head on Vijay’s shoulder here, but rather hovering just above it, and he has no idea she’s there:

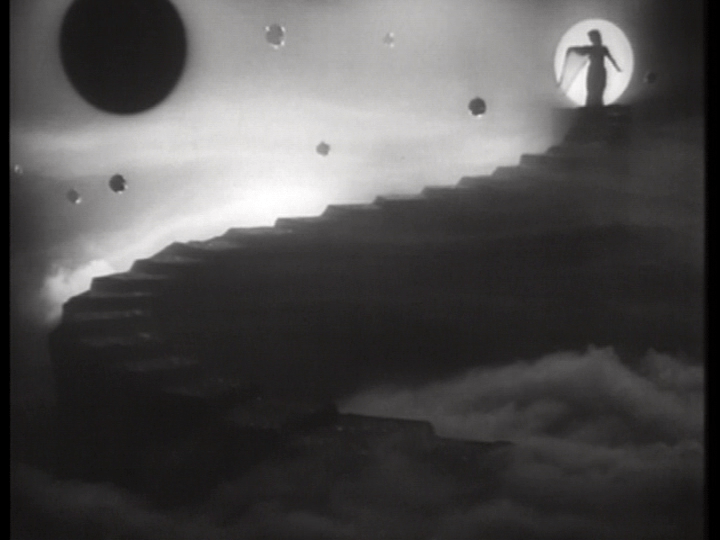

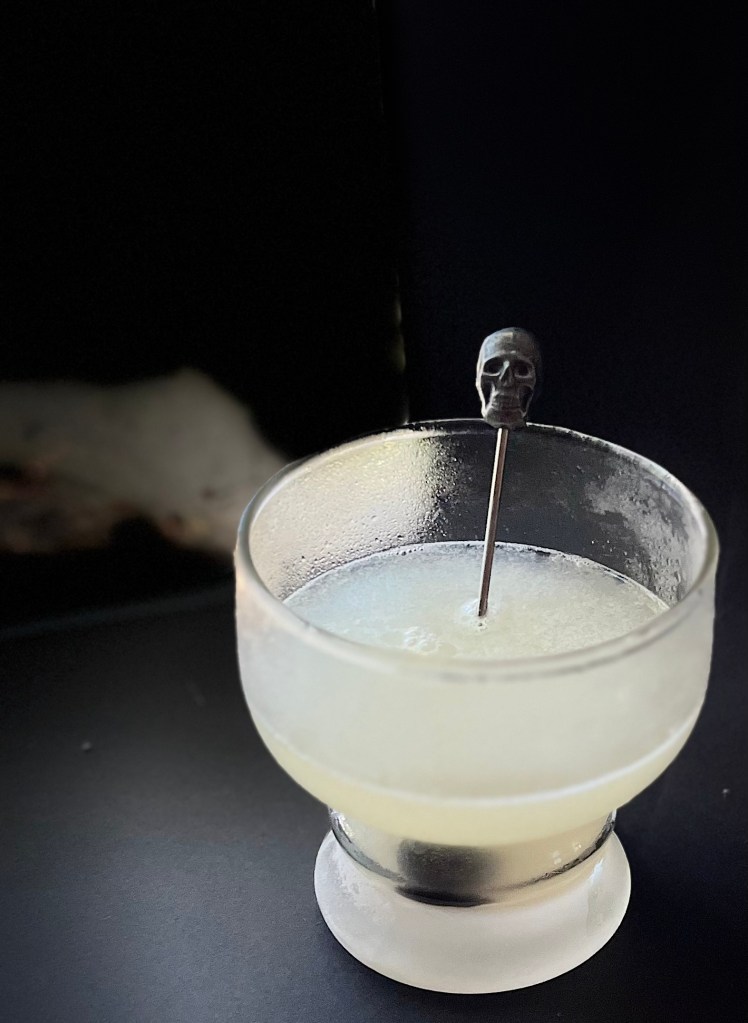

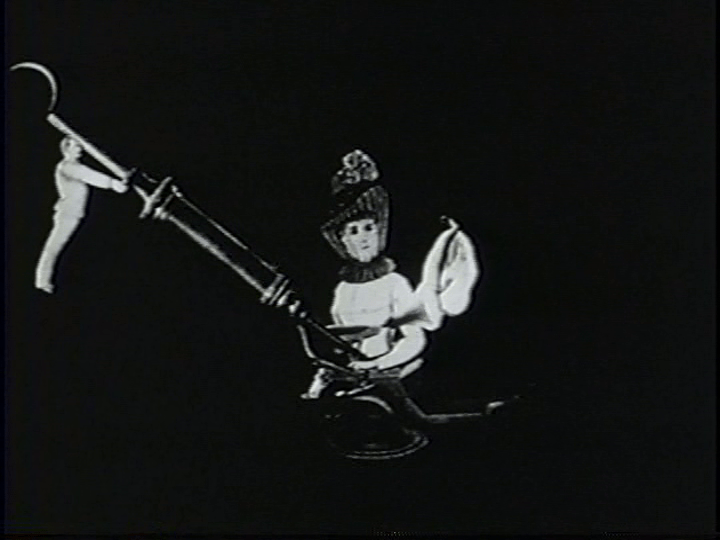

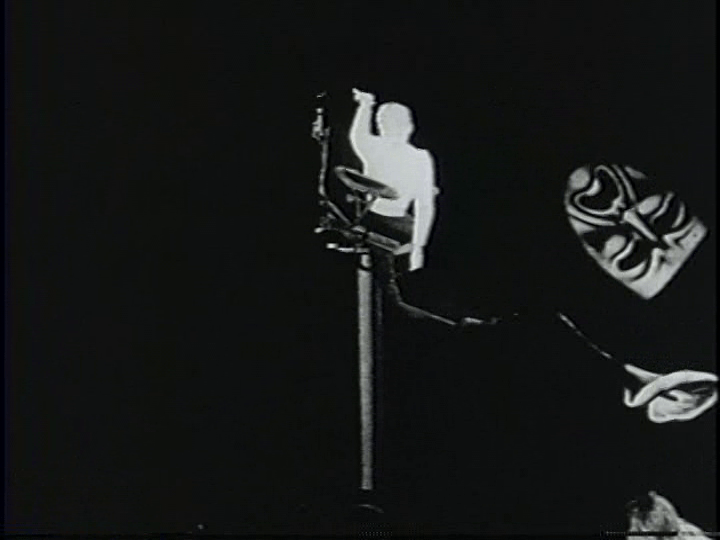

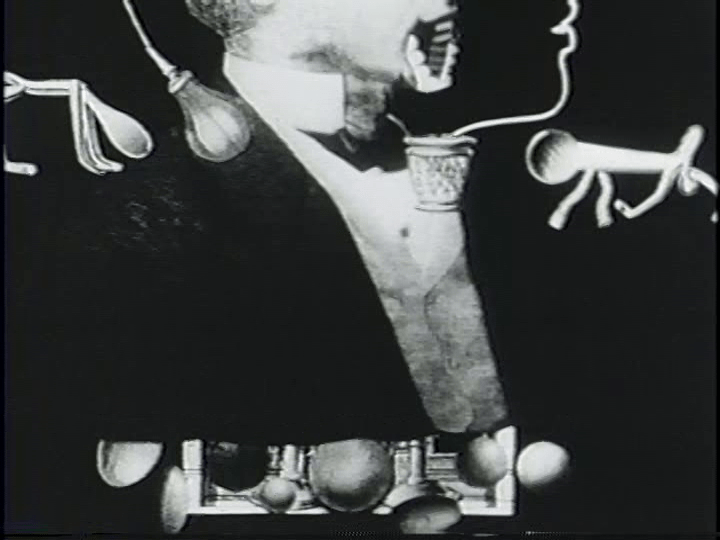

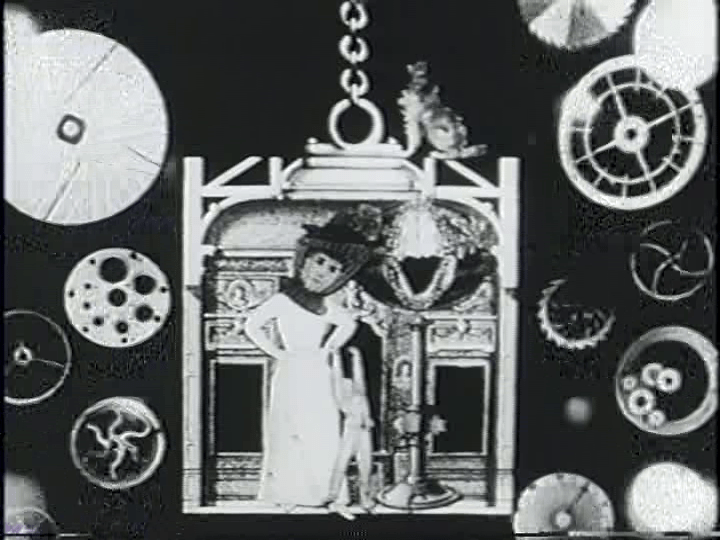

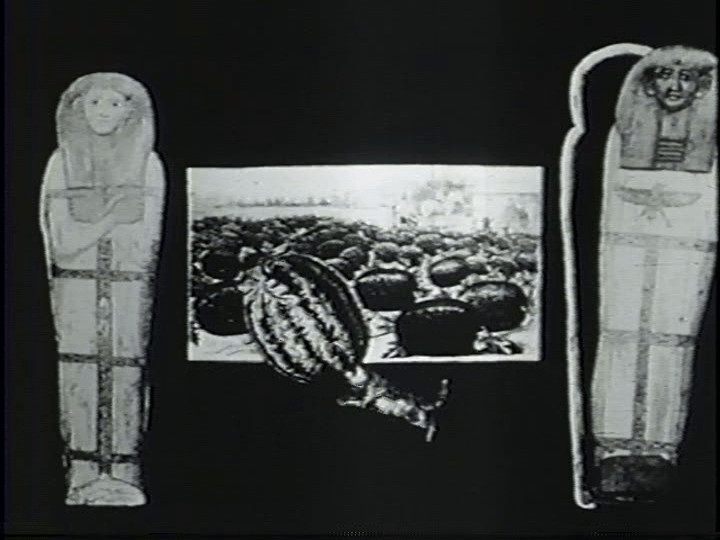

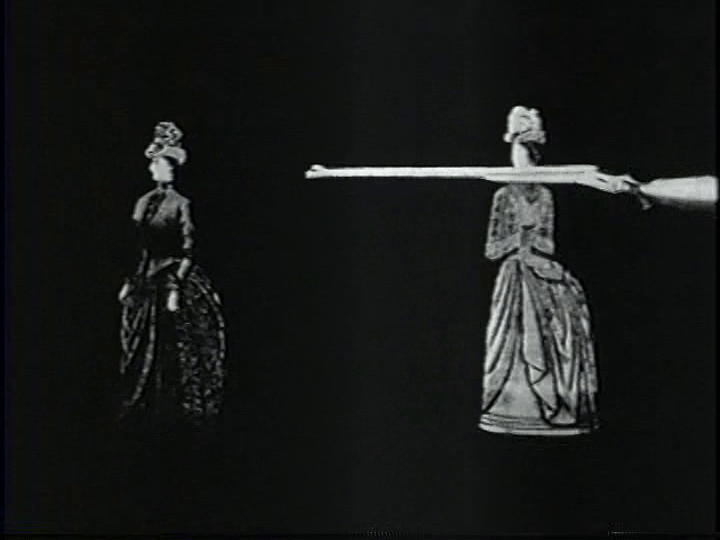

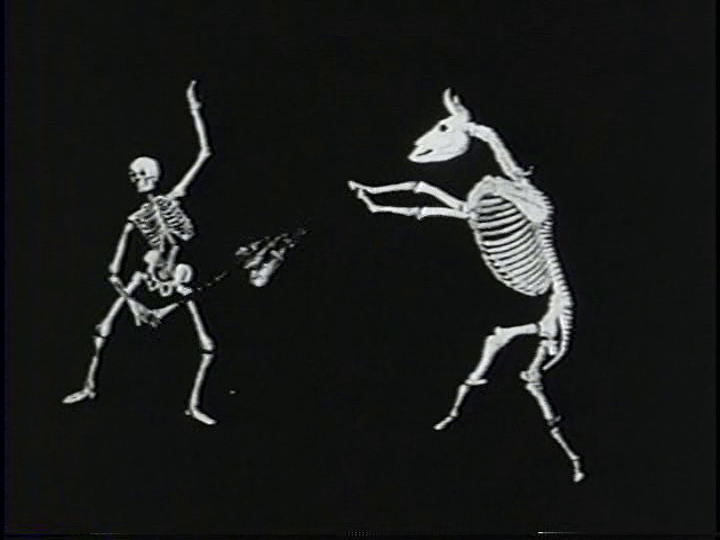

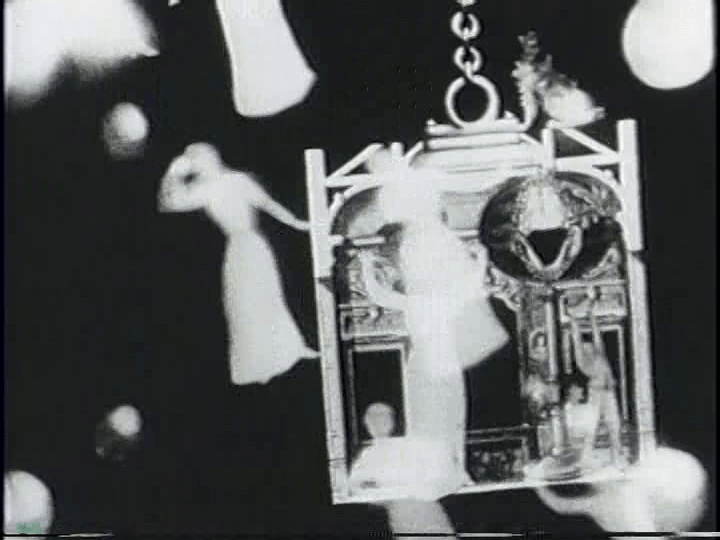

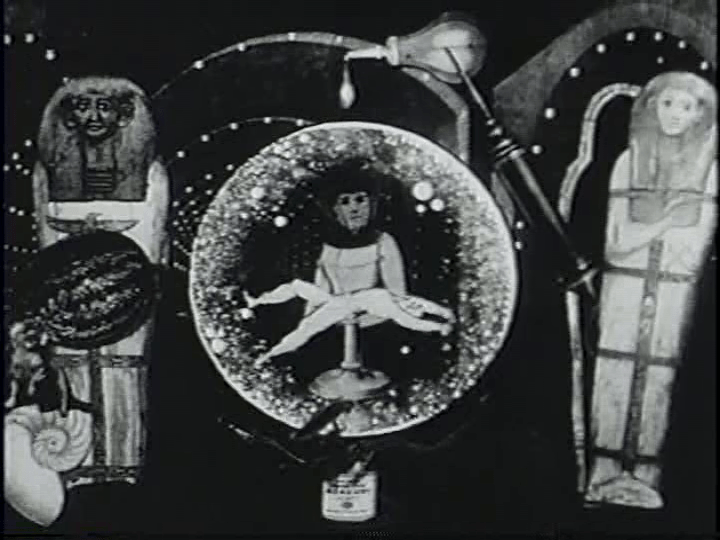

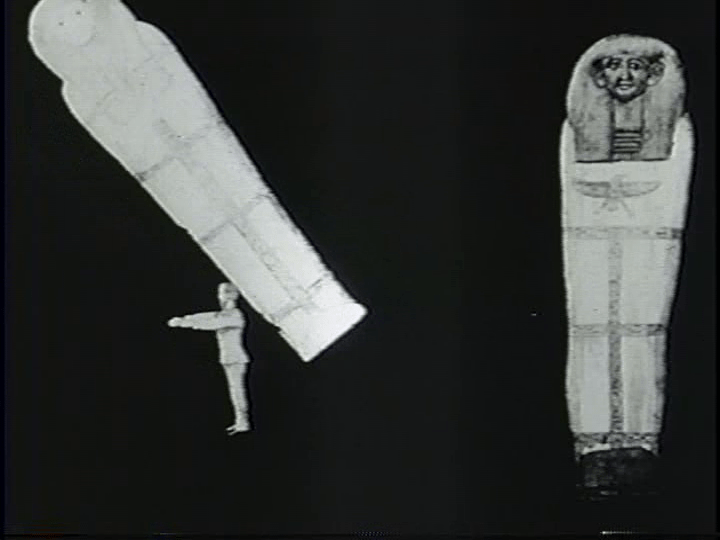

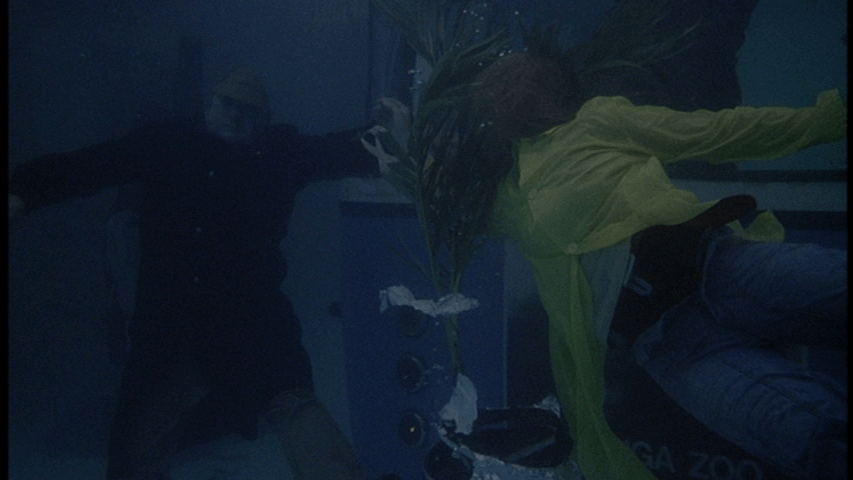

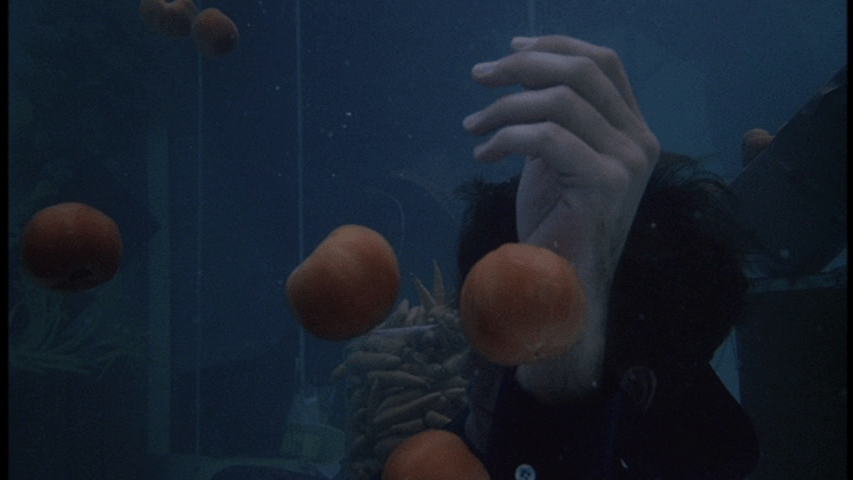

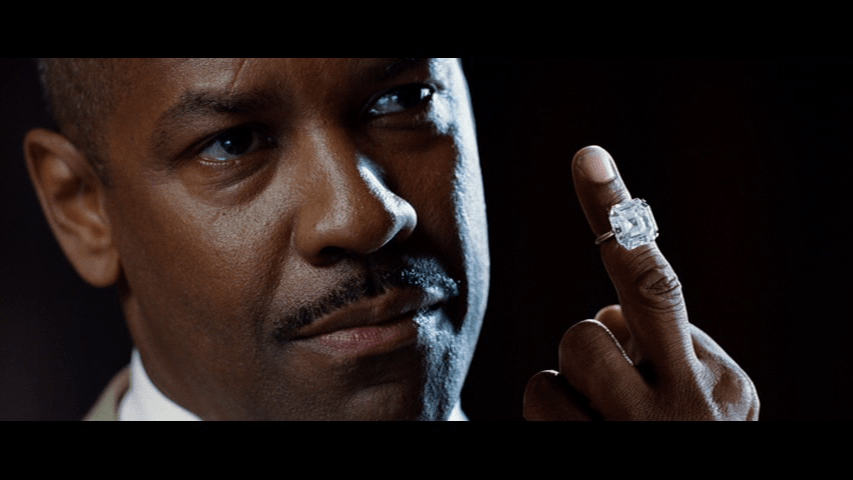

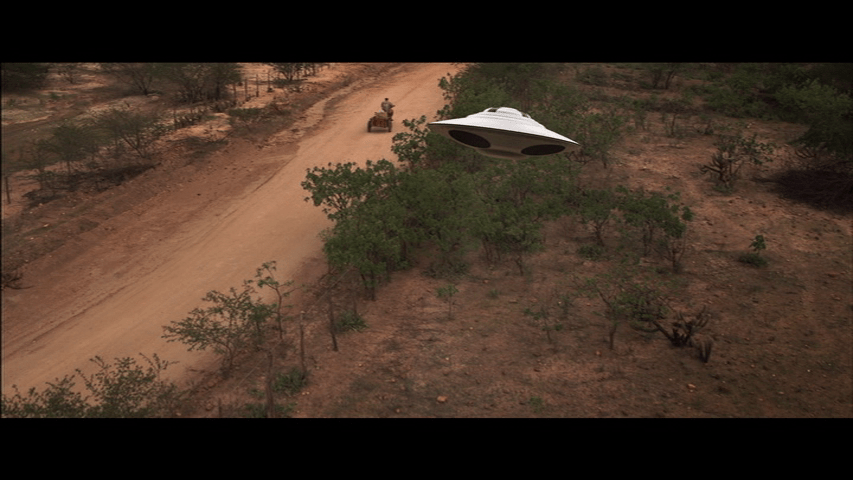

And the extravagant production design in “Hum Aap Ki Ankhon Mein,” which obviously inspired our Last Word photograph, is exactly what a daydream sequence within a flashback (!) calls for:

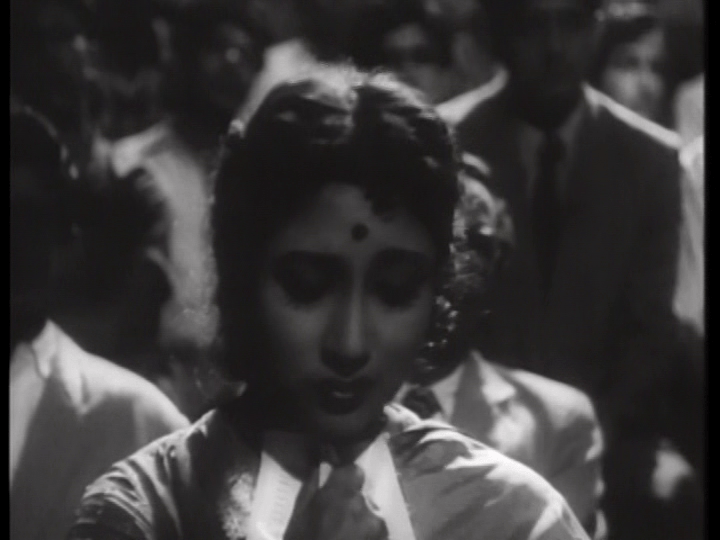

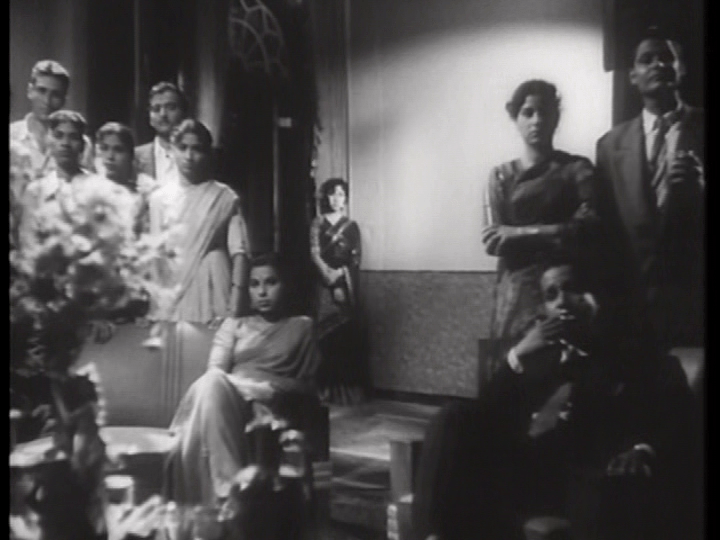

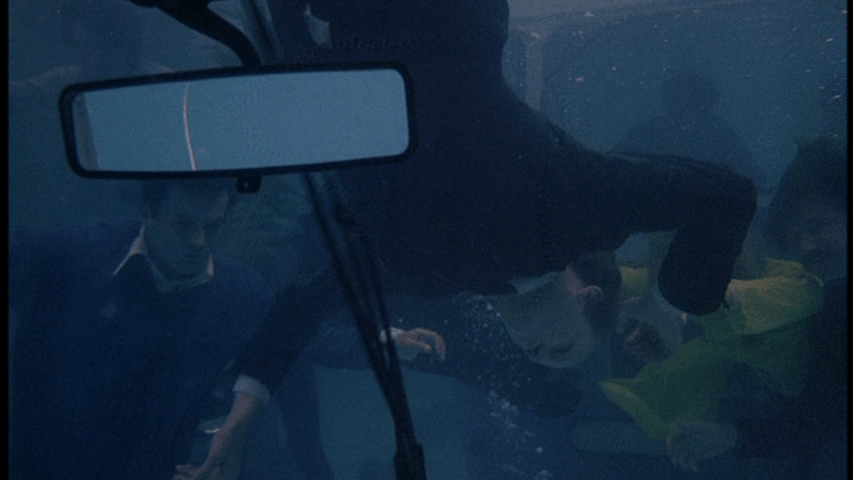

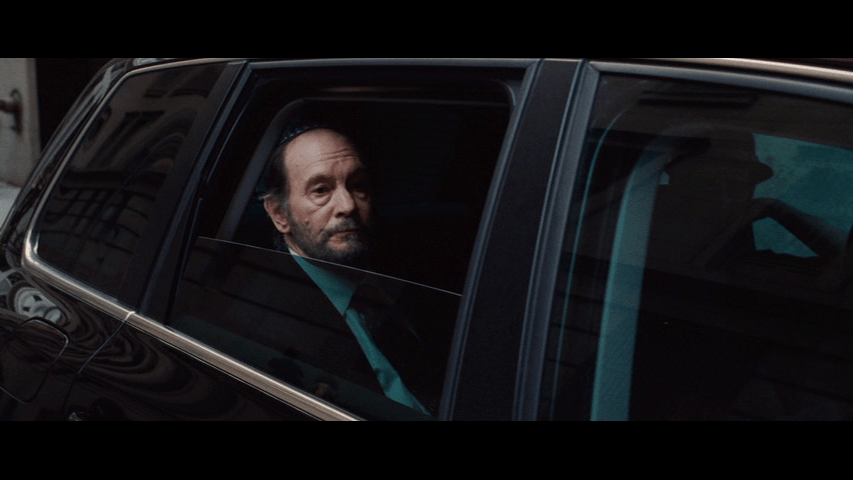

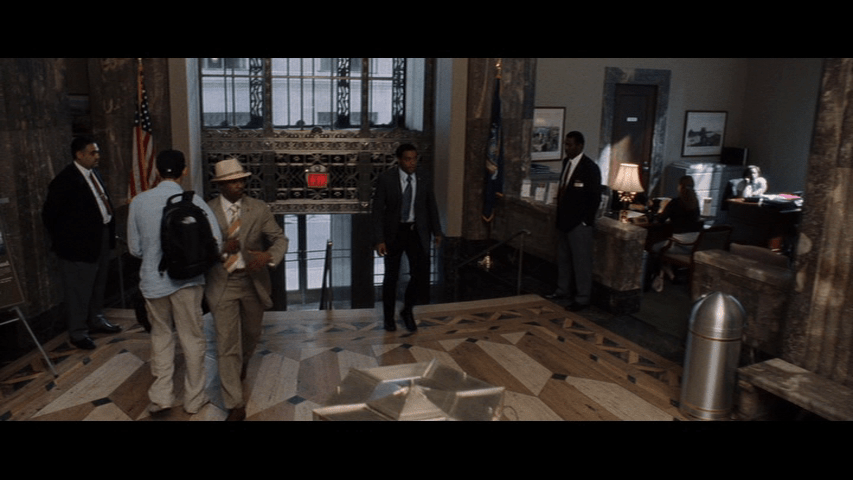

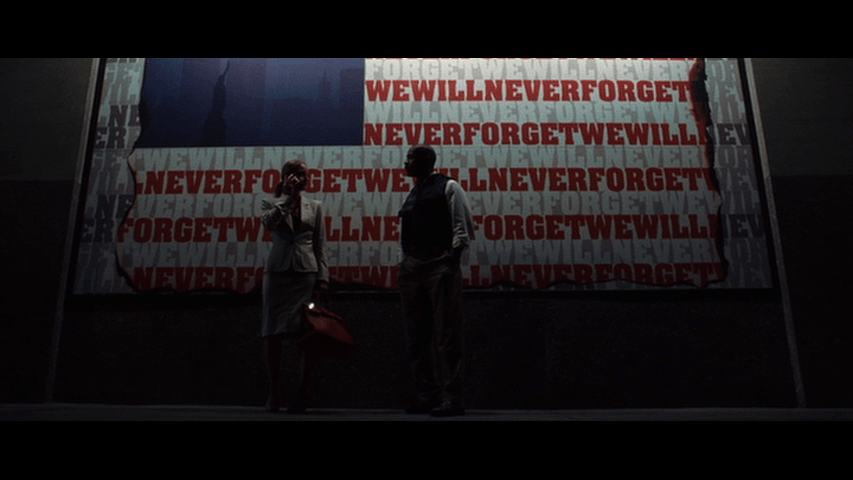

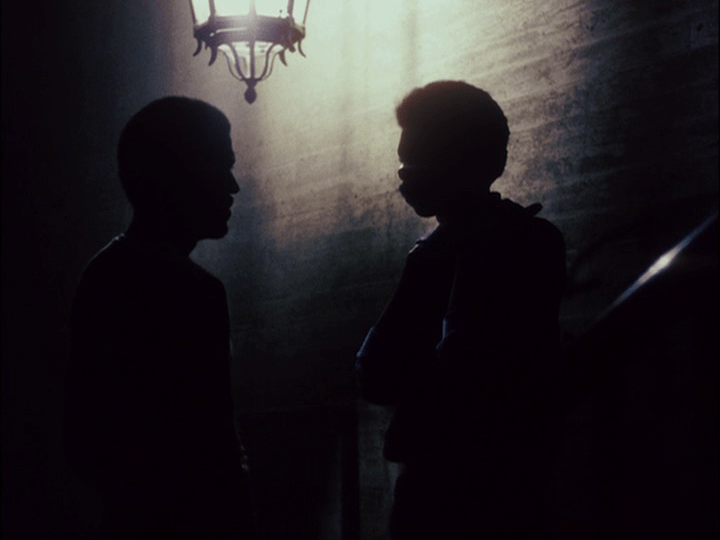

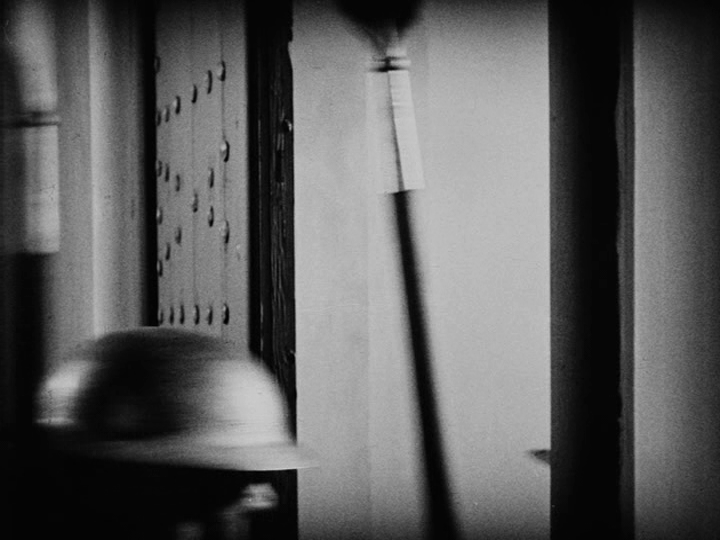

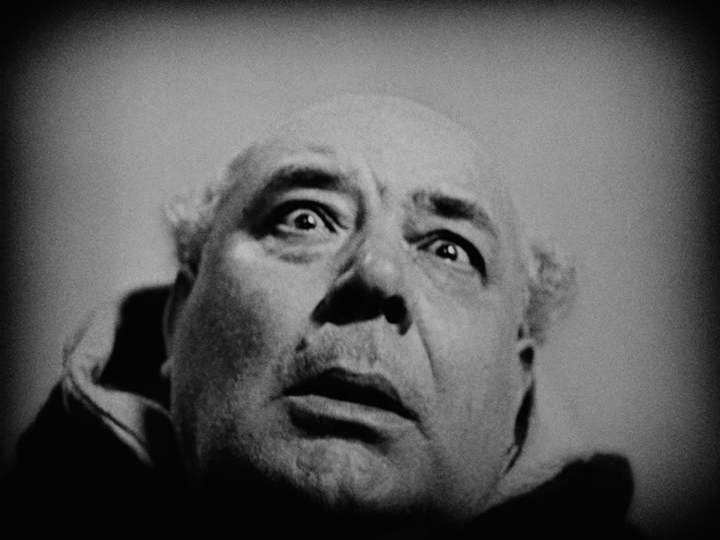

Dutt saves the best for last, though. “Yeh Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaye To” builds to a crescendo in some of the most incredible marriages of image and music ever captured on film. The scene takes place at a ceremony commemorating what is presumed to be the one-year anniversary of Vijay’s death. Mr. Ghosh (Rehman Khan), the publisher who organized it and the man who Meena married for money, breaking Vijay’s heart, knows that he is very much alive, as do Vijay’s half-brothers and his childhood friend Shyam (Shyam). Everyone else is shocked when the poet they only know through best-selling book that Gulabo paid Ghosh to publish “posthumously” appears at the back of the auditorium and begins reciting a verse railing against the corruption of the world:

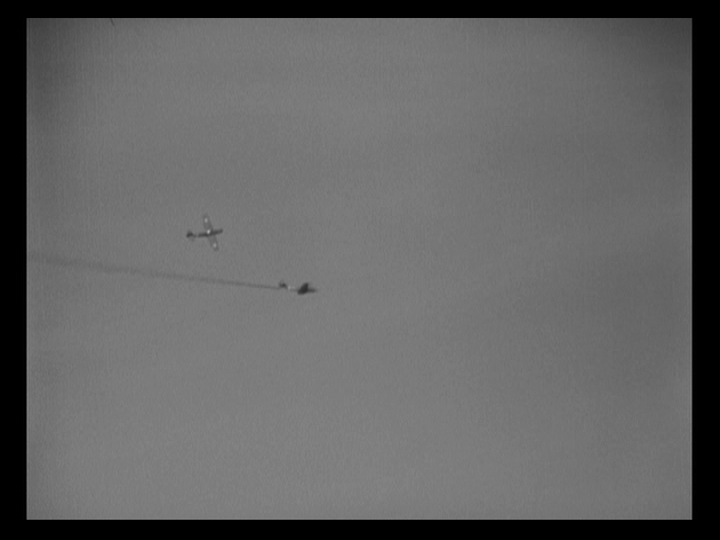

As Ghosh’s henchmen try to drag Vijay away, he breaks free of them and rushes forward as the camera pulls away from him, singing “burn this world! Blow it asunder!”

This scene is, in fact, primarily constructed of tracking shots, and they appear all throughout this film and the next and final one Gutt directed, Kaagaz Ke Phool. I consider them to be some of the most expressive camera movements in all of cinema. Creekmur says that “when the camera moves in and out throughout Pyaasa, it seems to replicate the physical act of breathing, or the opening and closing of the heart’s valves.” This is just about perfect, but it misses an important element: the velocity of the camera often changes during the movement, creating a disorienting effect like being on an elevator or a roller coaster, which to me feels like my heart skipping a beat or getting caught in my throat.

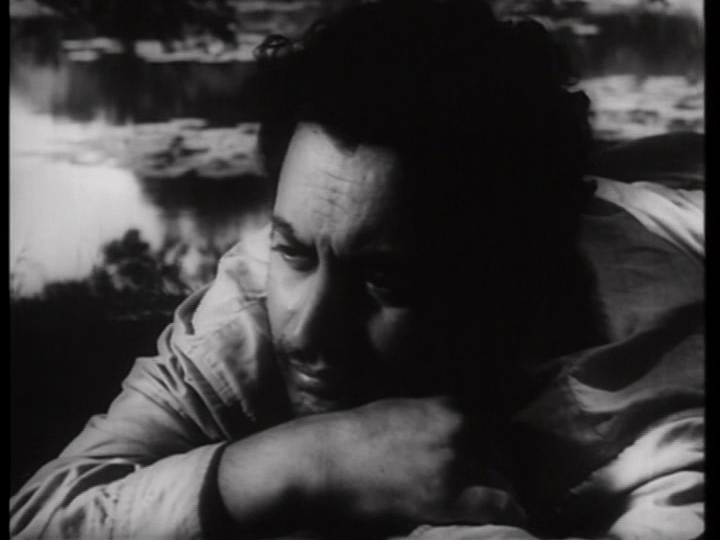

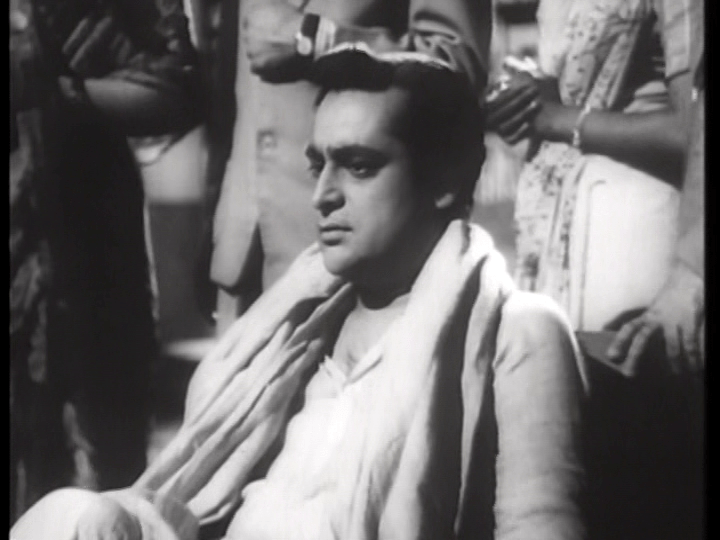

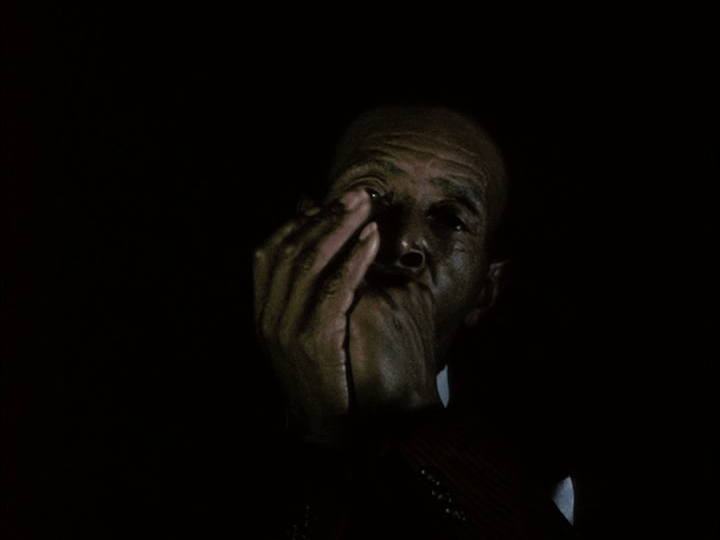

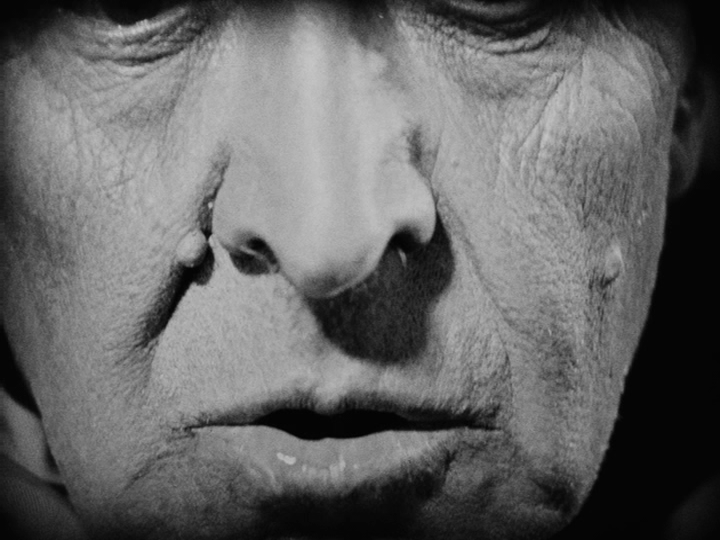

One of the best places to study these shots is during the scene where Vijay recites a poem for a reunion that his classmate Pushpa (Tun Tun) has told him about. As he spots Meena in the crowd, the camera tracks in to a close-up of his face then cuts to one of her which continues the motion:

As he begins to speak (“I am weary of this troubled life . . . “) the camera tracks away from him:

Then toward Meena and Ghosh, who is watching her intently, in the kind of rhythmic back-and-forth described by Creekmur:

The same thing happens as Vijay says “today I break all belief with the illusion of hope,” but with the addition of a sudden acceleration:

These shots also figure prominently in a scene in which Vijay, who Ghosh has hired to work as a servant at a literary party he is throwing, is moved to recite one of his own works in response to poems by two honored guests. Here and elsewhere the movements sometimes parallel each other, as when the camera tracks in first on Meena, then Ghosh:

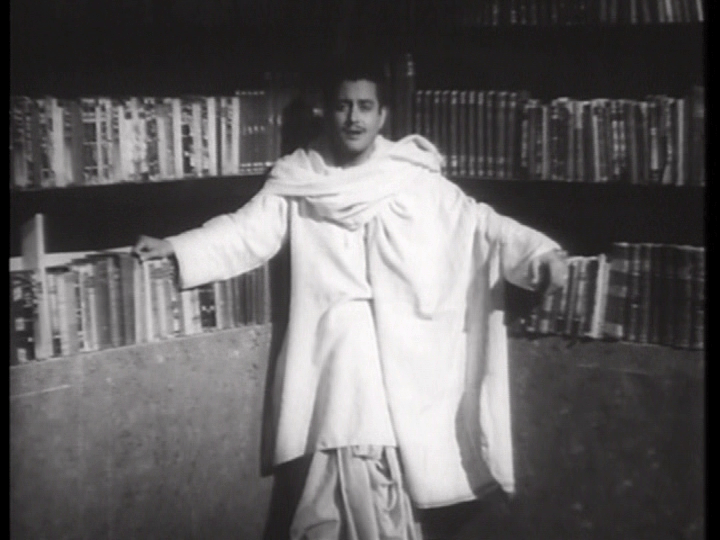

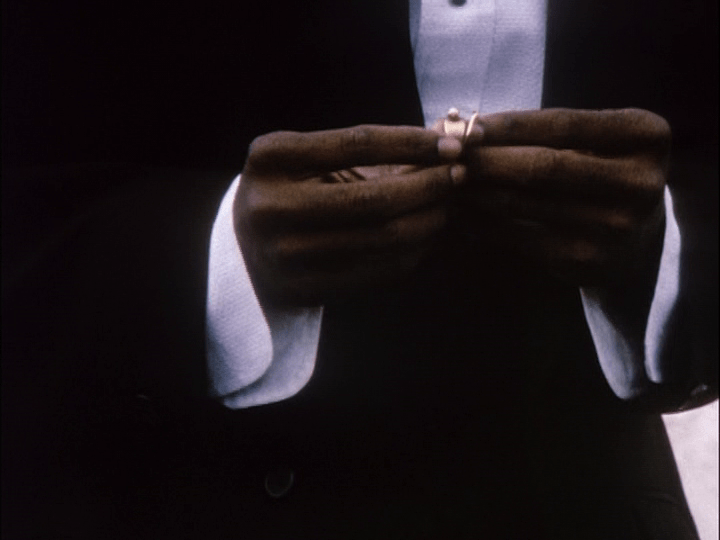

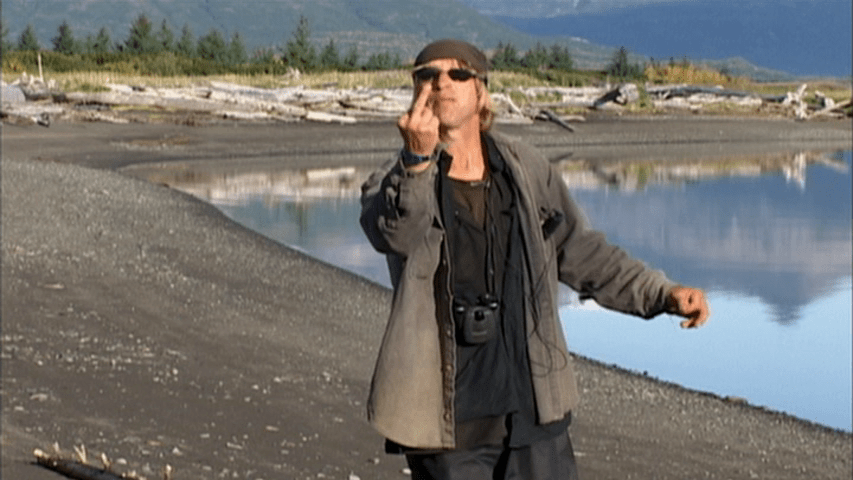

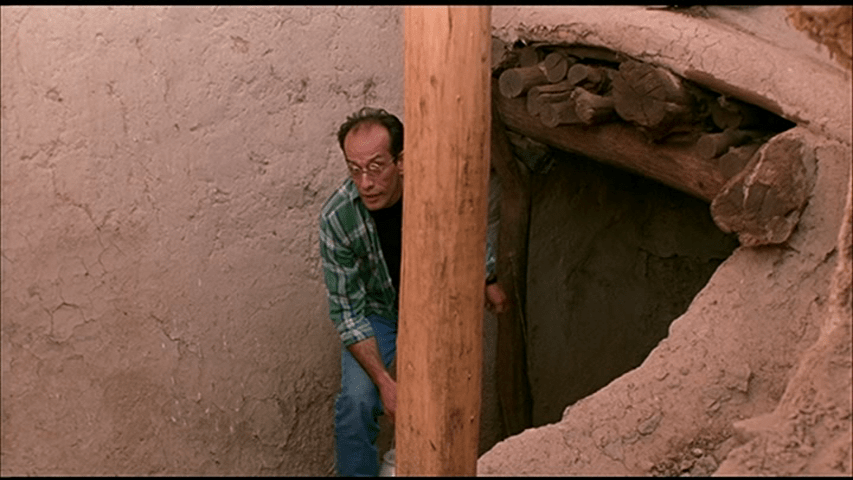

In both cases the effect is to link the emotional responses of characters to a common event, here Vijay’s manifestation as a savior who could rescue Meena from her unhappy life if only she could transcend her desire for wealth and high position in society. Any doubts that a first-time viewer might have about whether this should be considered a deliberately Christ-like pose:

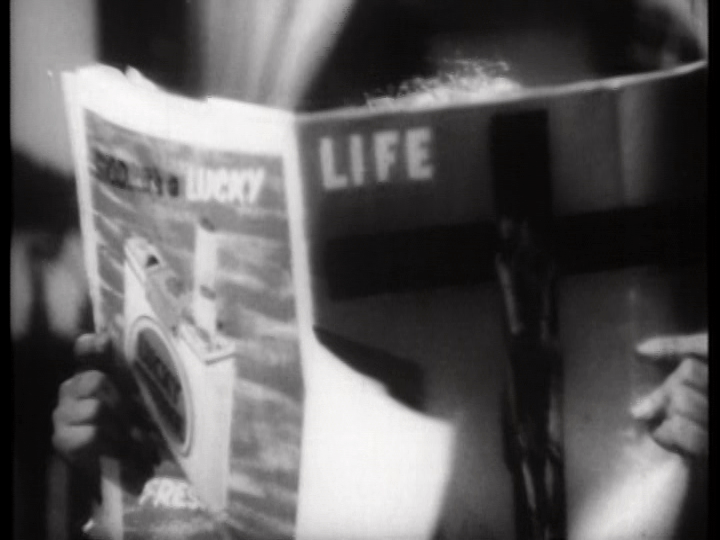

Will be laid to rest in either the next scene, in which Meena denies her love for Vijay to Ghosh three times, or if not then, when this Life magazine cover makes an appearance a bit later on:

Vijay spreads his arms wide again in the final reel:

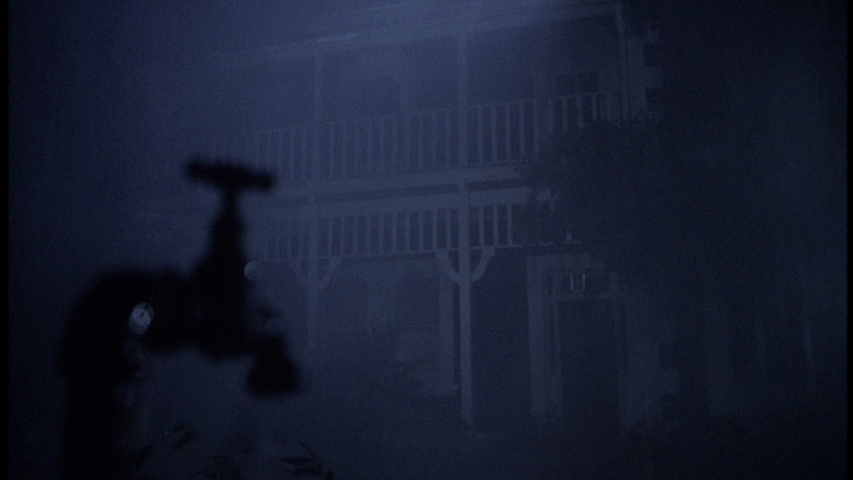

Which also contains a direct callback to Pyaasa‘s opening sequence when Gulabo falls and someone steps on her:

As was the case with the bee, I found the Christ imagery amusing at first, then precious, but ultimately embraced it as representing more than meets the eye. Jesus died so that the world’s sins could be forgiven; Vijay doesn’t die and as a result its hypocrisy is laid bare. This is at worst an intriguingly cynical inversion, but I agree with scholar Arun Khopkar’s (as translated by Shanta Gokhale) in-depth argument in Guru Dutt: A Tragedy in Three Acts that its use here is far more complex.

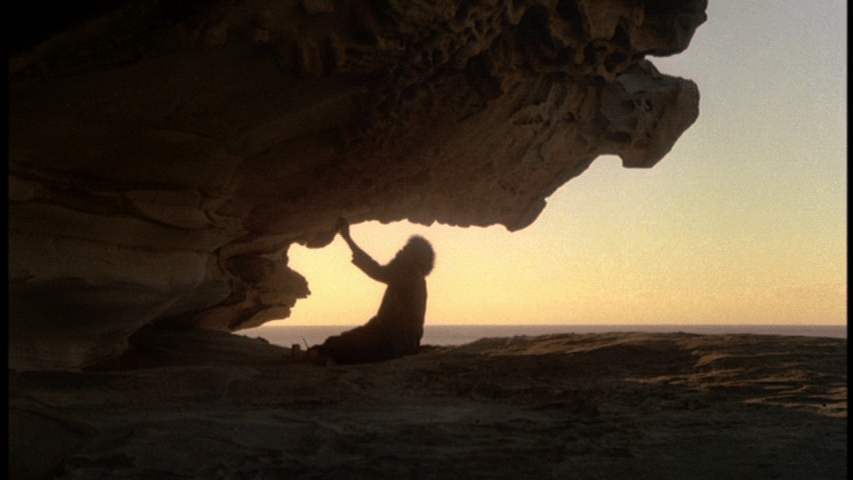

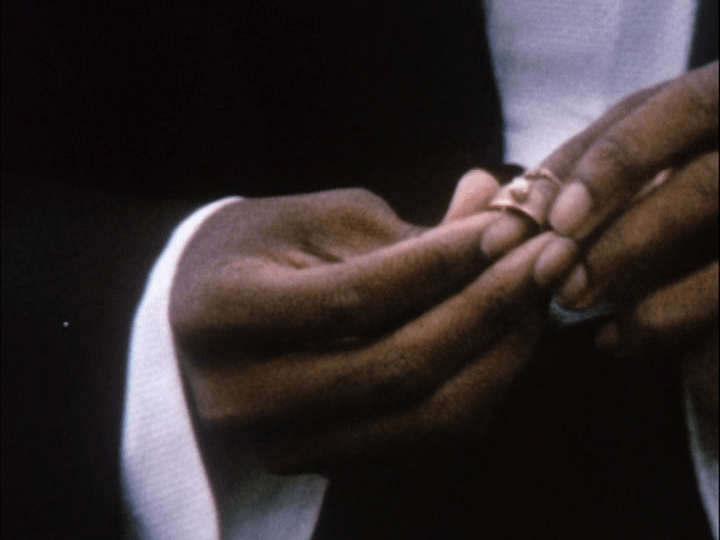

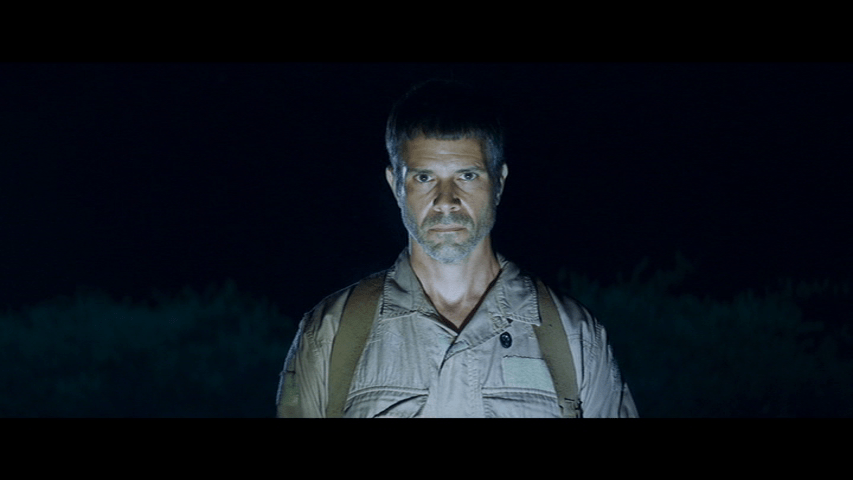

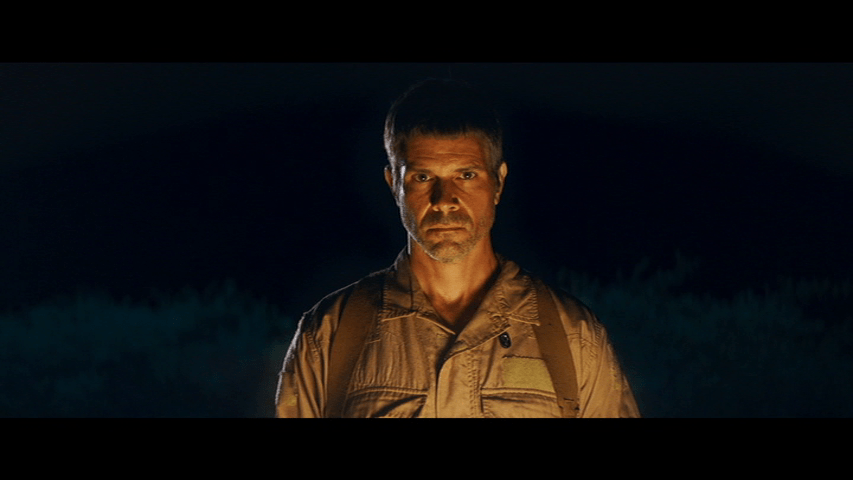

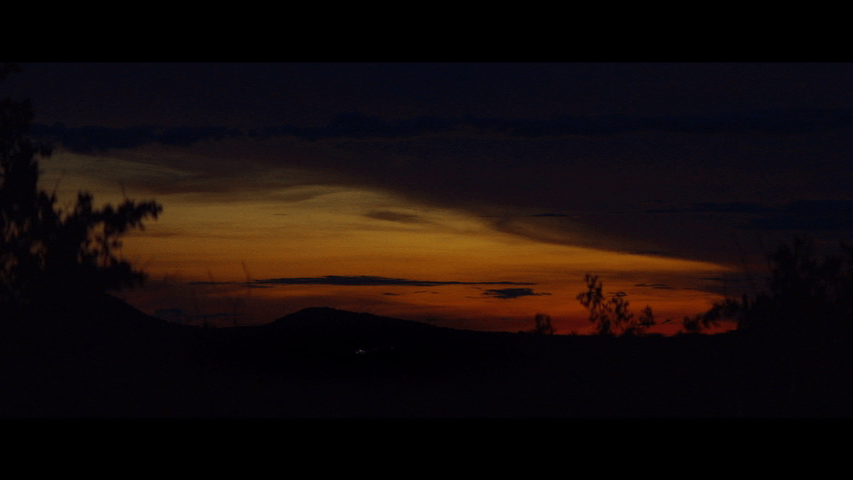

Pyaasa ends with Vijay and Gulabo literally holding hands and disappearing into the sunset together:

Guru Dutt’s younger brother Devi describes it brilliantly in a quote included in Guru Dutt: A Life in Cinema by Nasreen Munni Kabir as “a sort of [my italics] happier ending” than the one originally planned for the film. Here’s screenwriter Abrar Alvi’s account of it from the same book:

I believed that Vijay should not leave and go away in the last scene of the film, but that he should stay and fight the system. I told Guru Dutt, ‘Wherever Vijay goes he will find the same society, the same values, the same system.’ We discussed the scene at length, but I was overruled by Guru Dutt. So I wrote the ending in which Vijay comes to Gulab and tells her to go away with him to a place from where he will not need to go any further. I asked Guru Dutt, ‘Where does such a place exist in this world?’ But Guru Dutt put his foot down.

The 5,327,708.80 rupee question is, I think: will Vijay find it satisfying to, in the immortal words of Eden Ahbez, simply “love and be loved in return?” If I could wave a magic wand and conjure up a lavish Criterion Collection release of any film, it would be a box set of Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool. Perhaps I’ll wish for an essay answering this question to include in the booklet while I’m at it!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka my loving wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.