As I have mentioned previously, after I publish my last “Drink & a Movie” post in early 2026 I plan to edit all of them into a book. My chief model for this endeavor will be Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails by “Dr. Cocktail” Ted Haigh, which features a blend of images, drink lore, and practical advice in perfect proportions and which is spiral-bound for ease of use as all recipe books should be! Haigh’s version of the classic East India Cocktail has been in heavy rotation at our house since the end of raspberry season, so it seemed like a logical choice for this month’s drink. Here’s how we make it:

3 ozs. Brandy (Frapin VSOP)

1/2 oz. Raspberry syrup (we use the recipe below from Jeffrey Morgenthaler’s The Bar Book)

1 teaspoon Maraschino liqueur (Luxardo)

1 teaspoon Ferrand Yuzu Dry Curaçao

1 dash Angostura Bitters

Make the raspberry syrup by simmering two cups of fresh raspberries with eight ounces of water in a medium saucepan for five to ten minutes until everything is approximately the same color, then strain. Add one cup of sugar while the mixture is still hot, stir until dissolved, let cool, then bottle and refrigerate. Make the cocktail by stirring all ingredients with ice and straining into a chilled glass. Garnish with a cherry.

The East India Cocktail is an elegant beverage. Haigh explains that it “was named not for the eastern part of India but for all of it and more: India, Burma, Malaya, Singapore, and the entirety of the British colonies.” This therefore struck me as a perfect opportunity to break out the bottle of yuzu Curaçao I picked up at The Wine Source in Baltimore last winter since I associate it with that corner of the world more than its West Indian cousin. The dominant flavor is of course cognac (there are three ounces of it, after all), but the other ingredients serve the same function as the atmosphere at the palace of Mopu, where most of this month’s movie Black Narcissus takes place: they exaggerate everything. So it’s fruitier, sweeter, more mysterious cognac. Speaking of which: considering how much of it you’re going to use, it’s definitely worth splurging on a good bottle! Frapin VSOP was a recommendation by someone at Ithaca’s always reliable Cellar d’Or and we like it here and to sip on its own quite a bit.

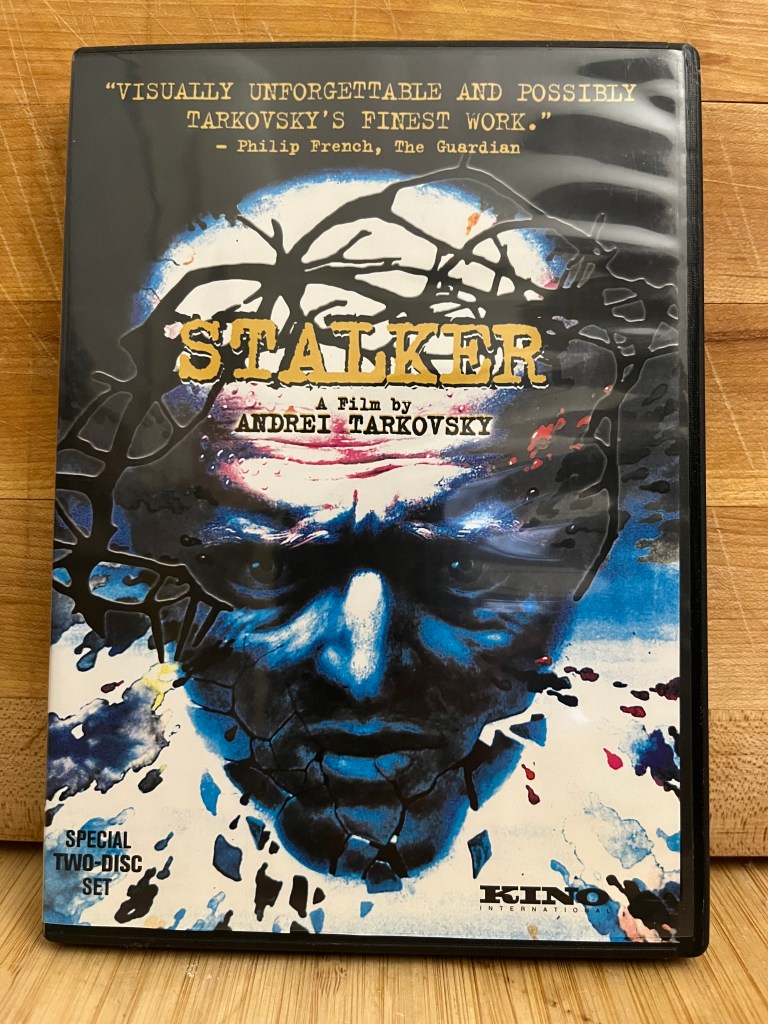

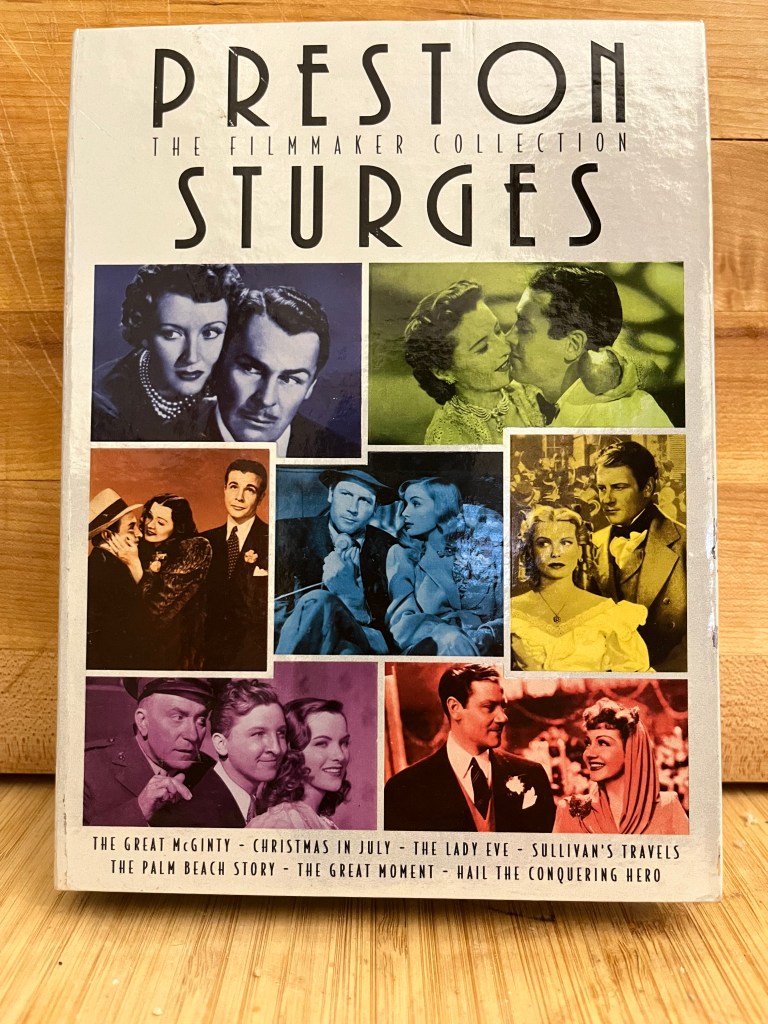

Black Narcissus is set in the part of the British Empire that the East India Cocktail is named after, and it has been on my mind ever since I was fortunate enough to see it at last year’s Nitrate Picture Show, so it was an obvious way to complete the pairing. Here’s a picture of my Criterion Collection DVD release:

It can also be streamed via The Criterion Channel and a number of other commercial platforms for free, with a subscription, or for a rental fee. Some people (including current Cornell University faculty, staff, and students) may have access to it through Kanopy via a license paid for by their local academic or public library as well.

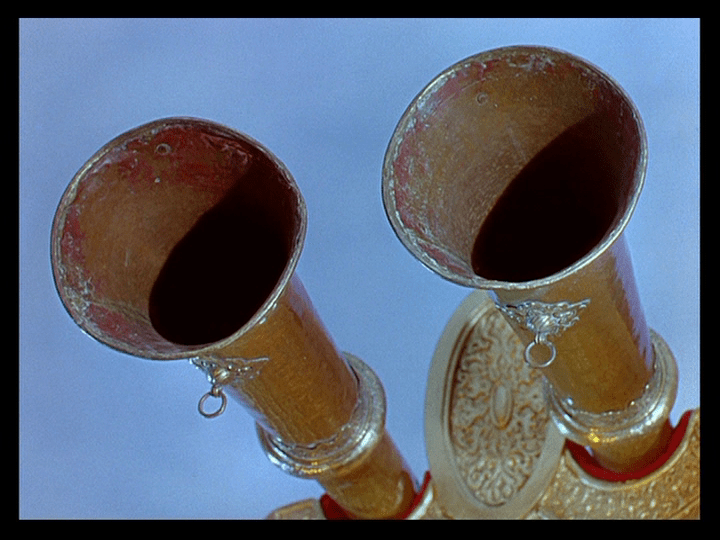

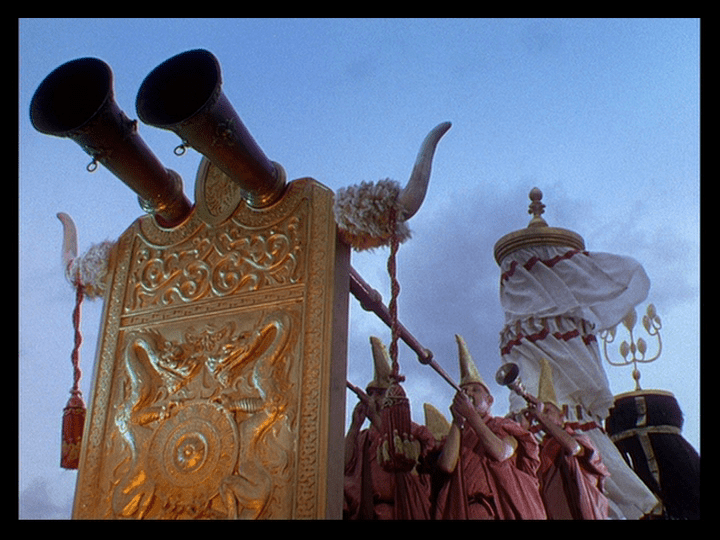

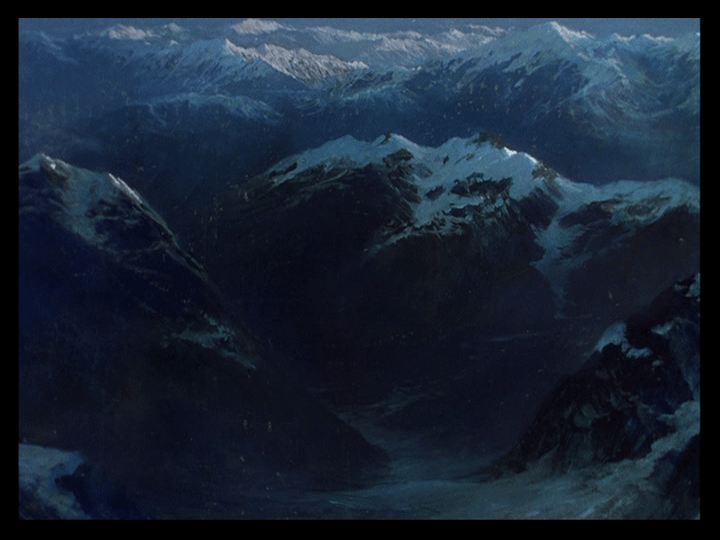

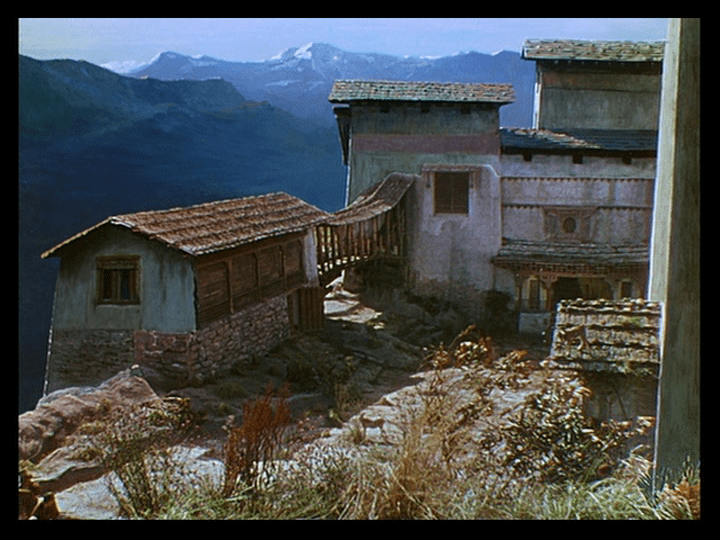

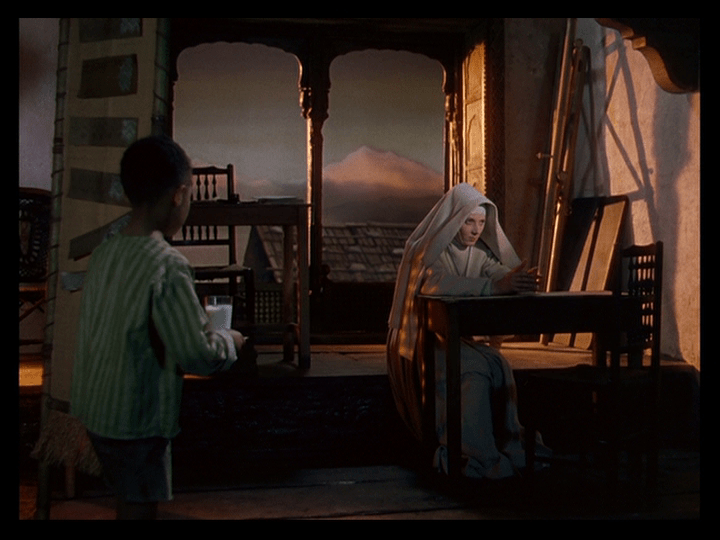

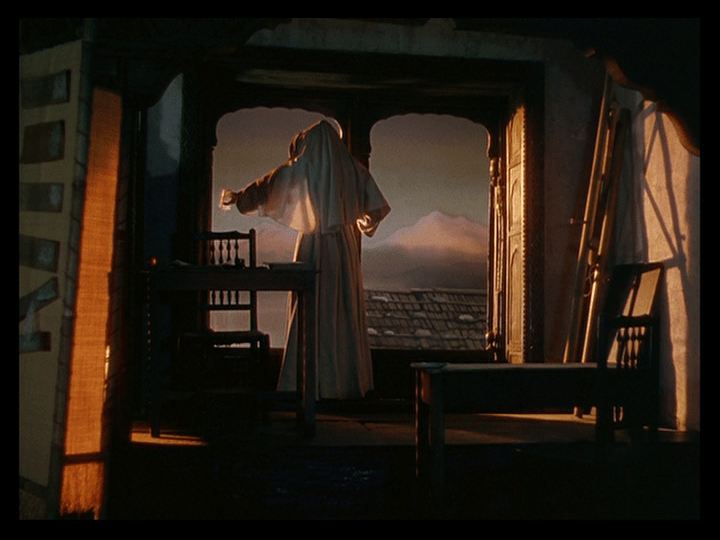

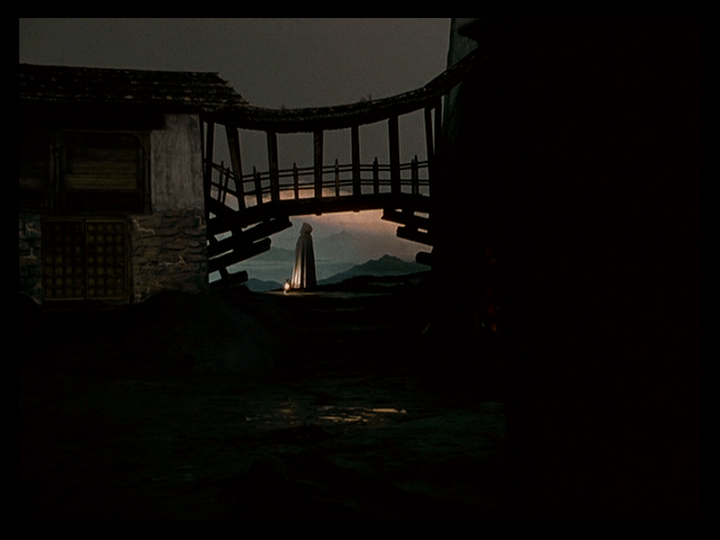

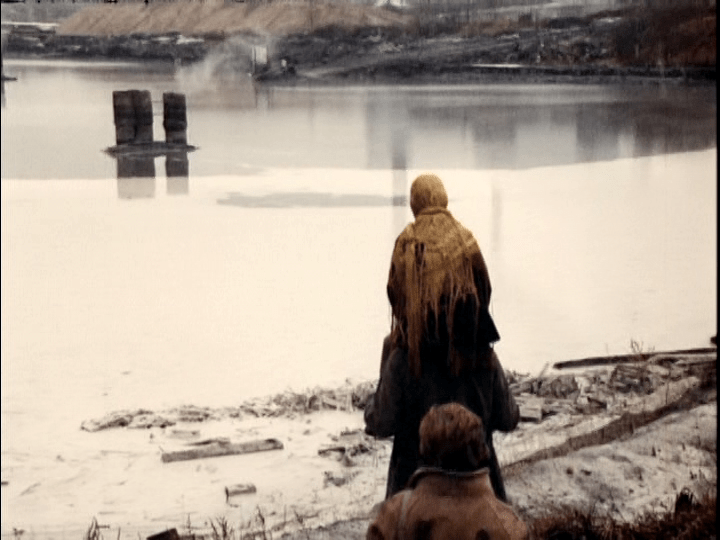

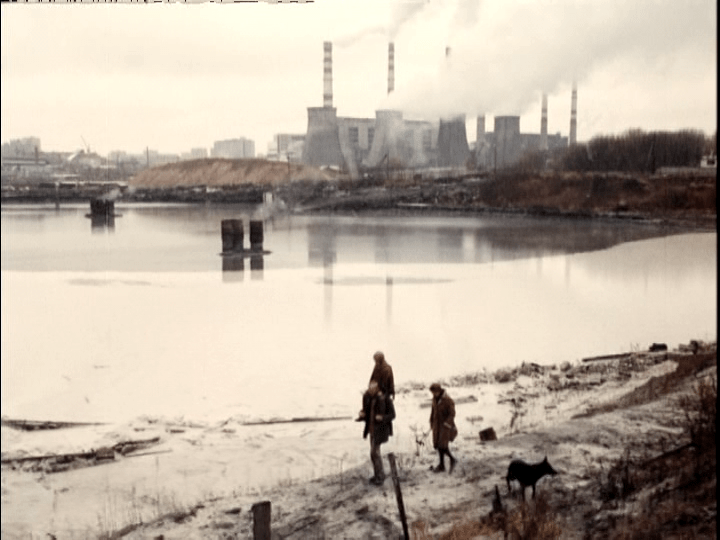

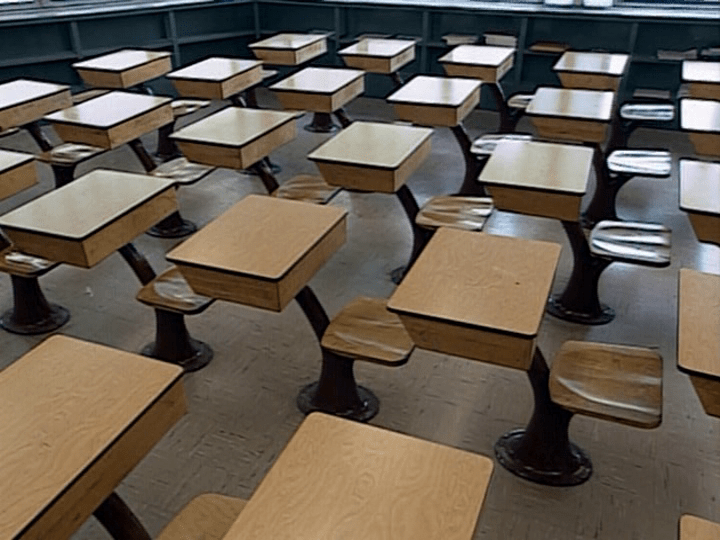

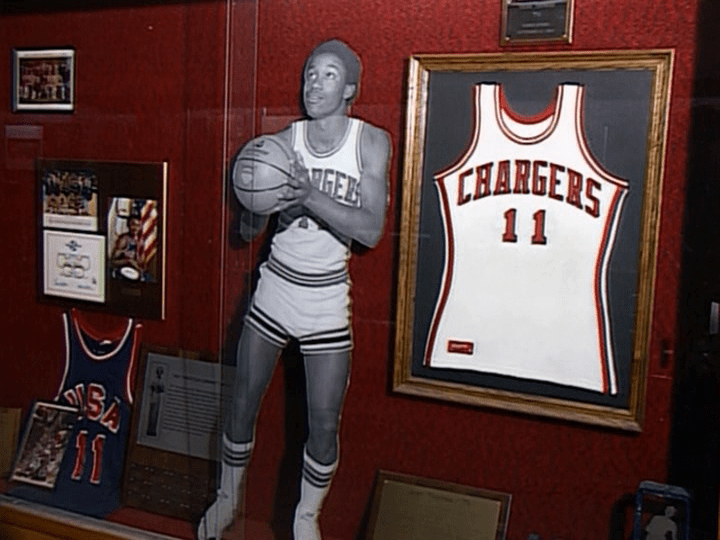

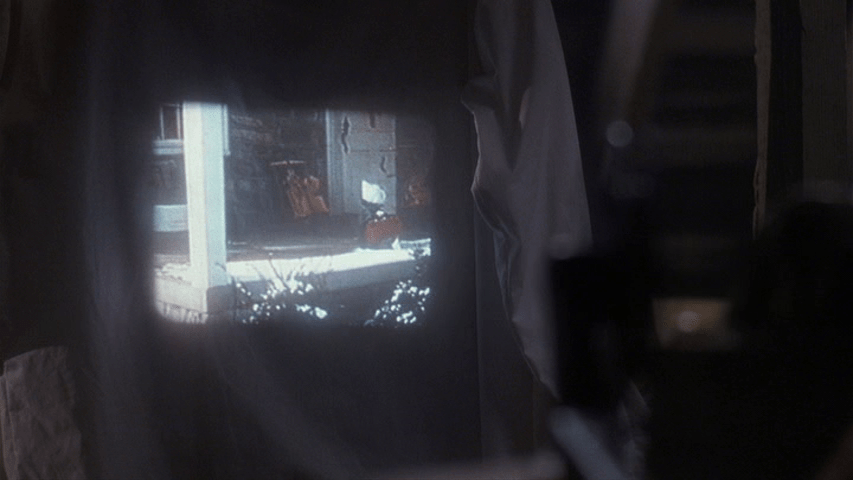

Thanks to brilliant Oscar-winning art direction by Alfred Junge and cinematography by Jack Cardiff, along with stunning matte paintings by W. Percy Day, Black Narcissus is one of the most transportative films ever shot entirely in a studio. It begins with a series of shots that establish the setting:

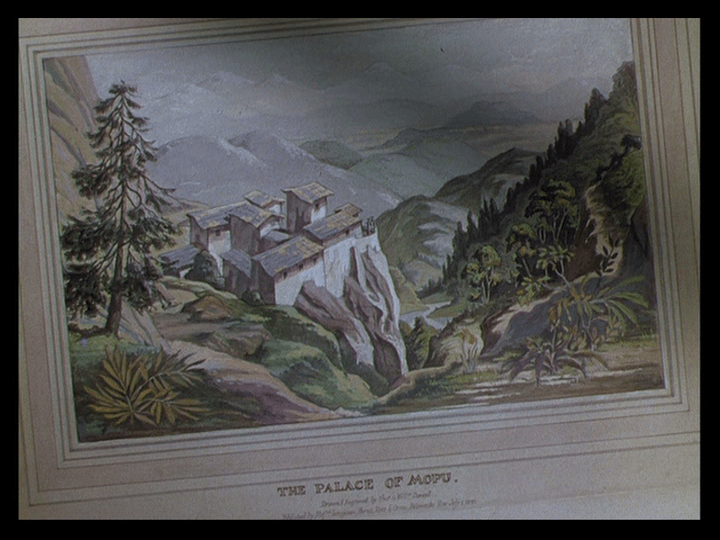

This is followed by an introduction to Mopu, which the Order of the Servants of Mary plans to convert into a convent, that Priya Jaikumar notes “is filtered through three people, all of whom are less than objective about the place and the nuns’ mission.” We see it first through the eyes of Reverend Mother Dorothea (Nancy Roberts), who ponders an illustration in a book:

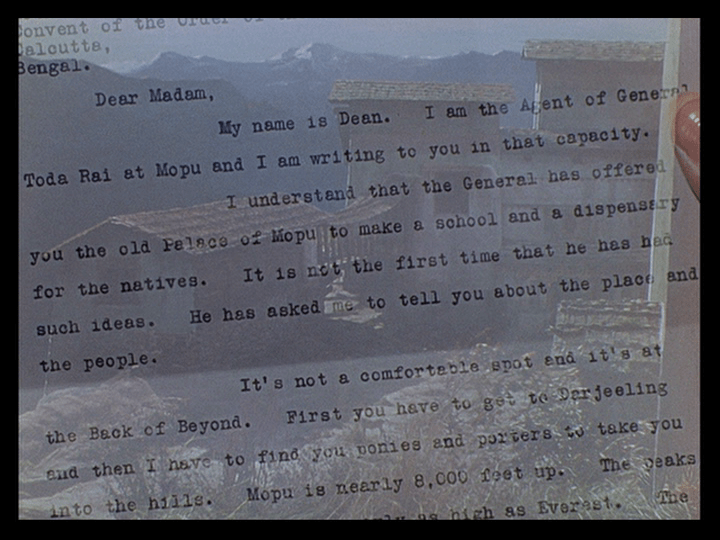

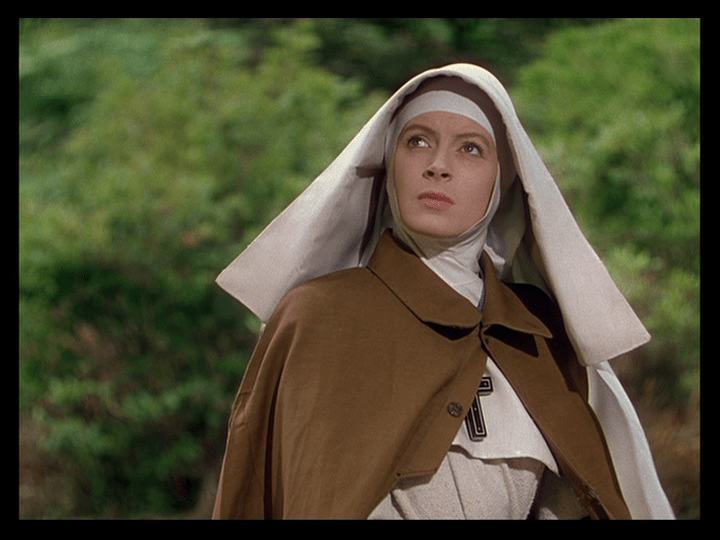

Then Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr), who is being sent there as the order’s youngest Sister Superior, imagines it as she reads a letter from Mr. Dean (David Farrar), the British agent of The Old General Toda Raj (Esmond Knight) who has given it to them:

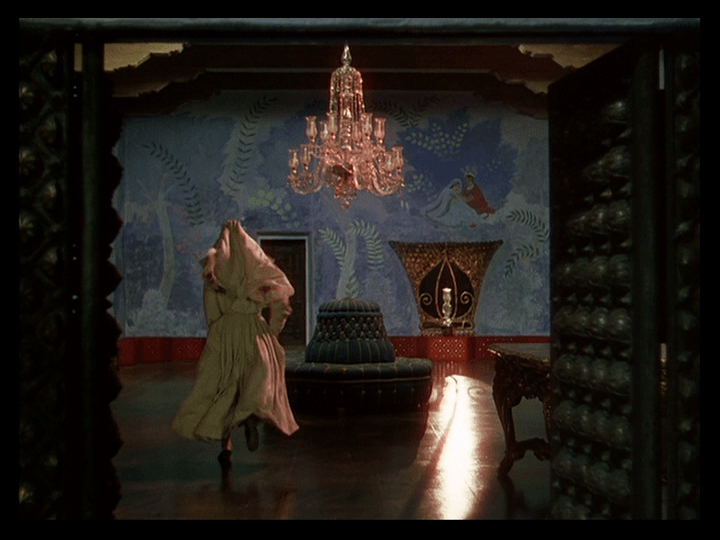

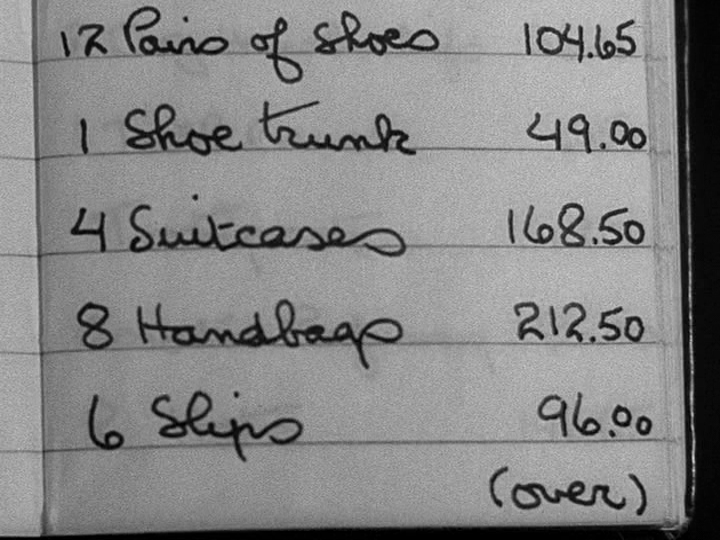

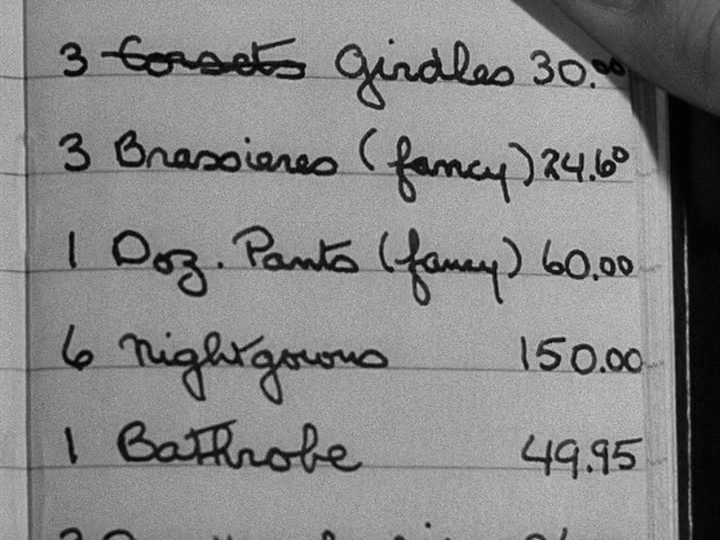

Mr. Dean’s letter reveals that the General’s father previously housed his concubines in Mopu:

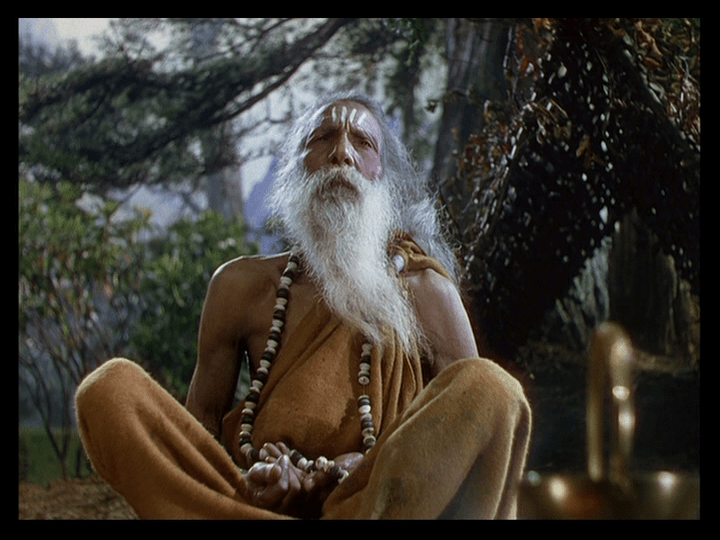

And introduces us to the local holy man who sits motionless day in and day out with his face to the mountains:

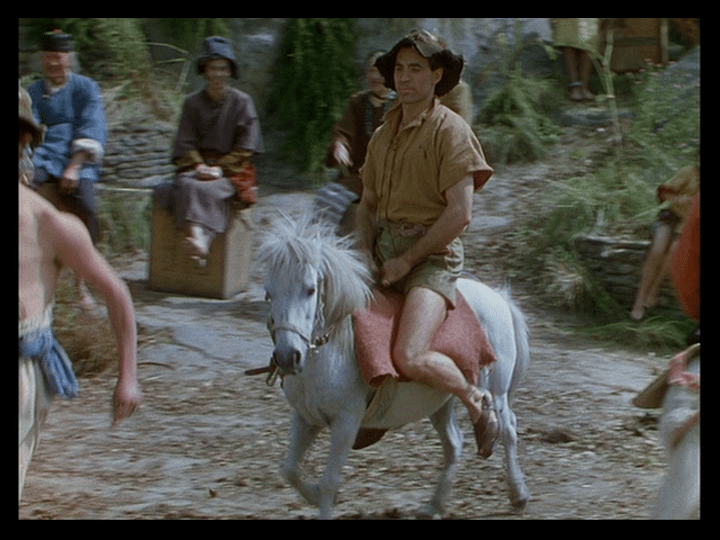

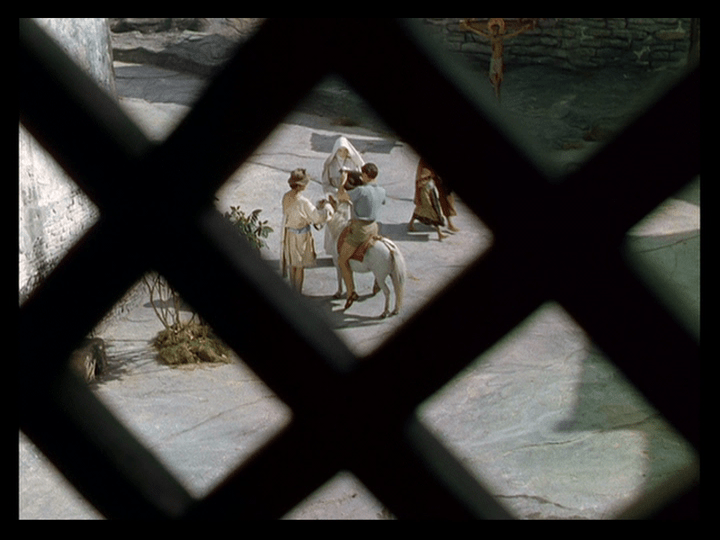

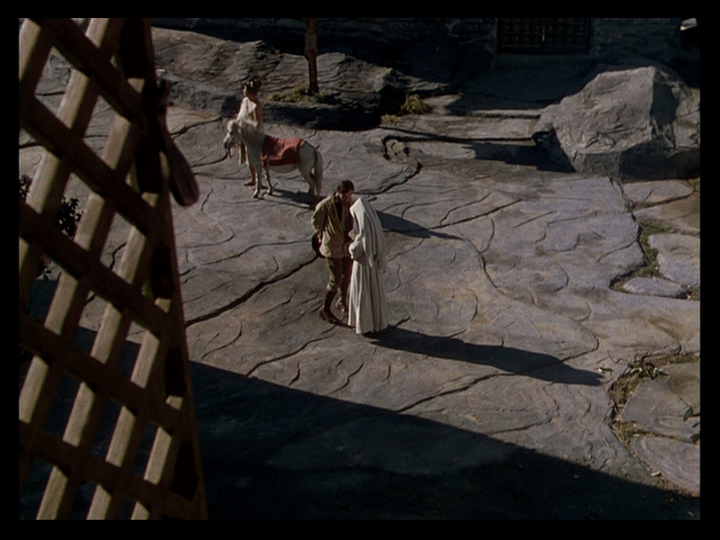

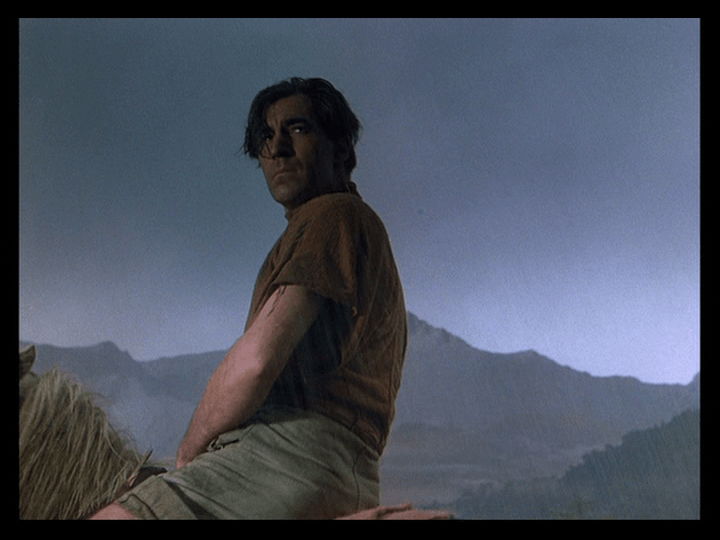

Before seamlessly transitioning into a depiction of the General giving instructions to Mopu’s housekeeper Angu Ayah (May Hallatt) and Mr. Dean, who we see for the first time riding a pony that is absurdly small for a man of his height:

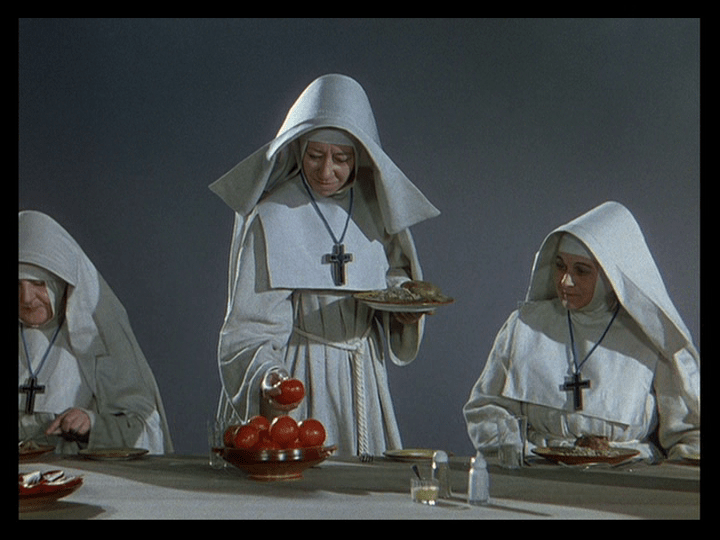

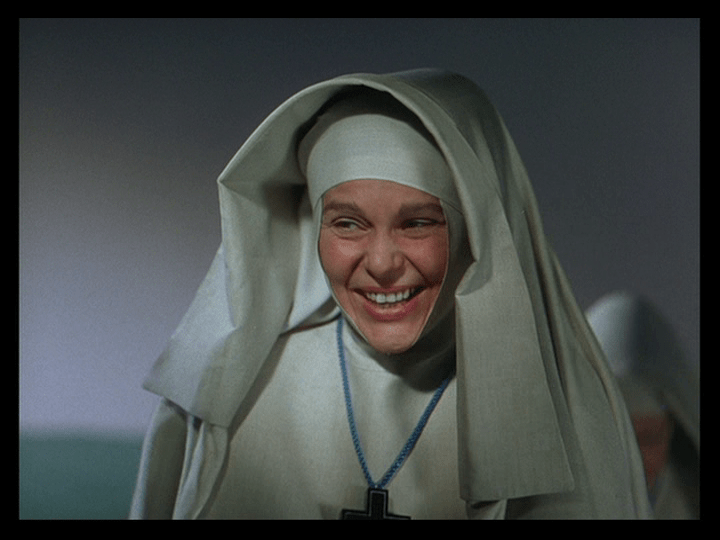

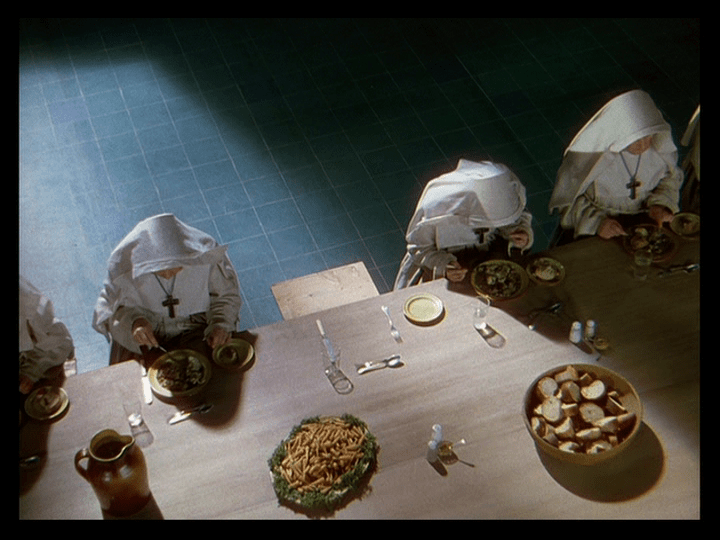

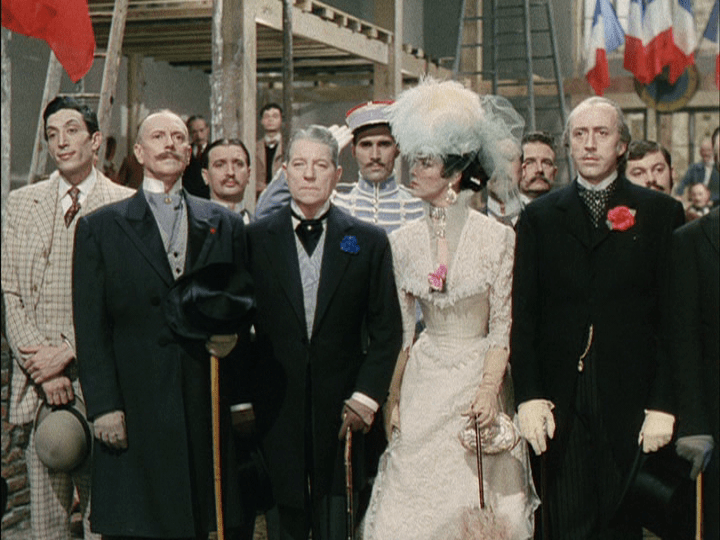

The rest of the nuns who will occupy Mopu, or Saint Faith as it is now to be called, are introduced in the next scene, which per Roderick Heath is reminiscent of “the kind of war movies where a team of talents is assembled for a dangerous mission in enemy territory.” There’s Sister Briony (Judith Furse), the strong one; Sister Philippa (Flora Robson) for the garden; and Sister Blanche or “Honey” (Jenny Laird), because Sister Clodagh will need to be popular:

As well as Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron) because “she’s a problem,” but “with a smaller community, she may be better.” Sister Ruth is initially represented as an empty place at the convent’s dinner table:

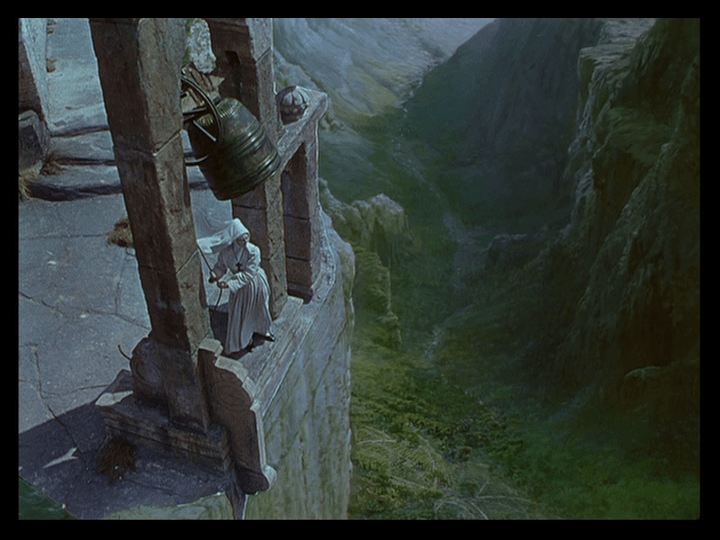

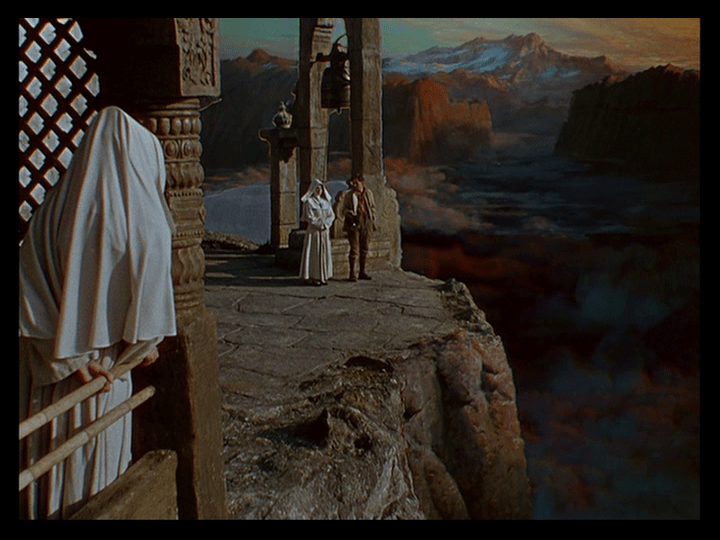

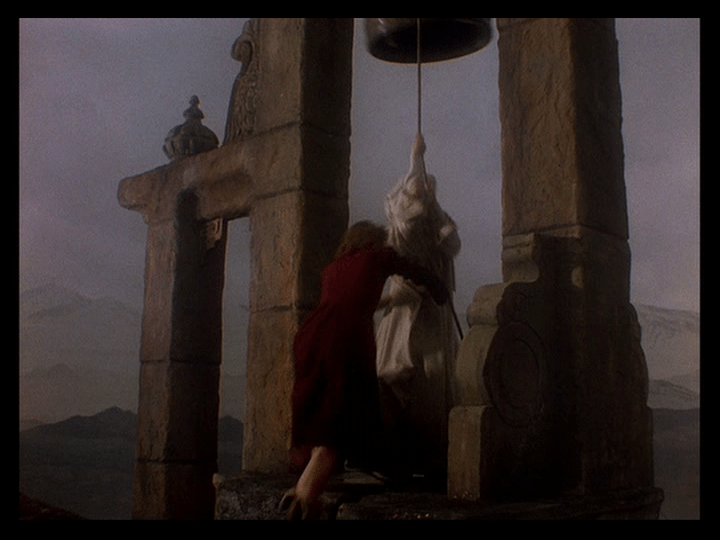

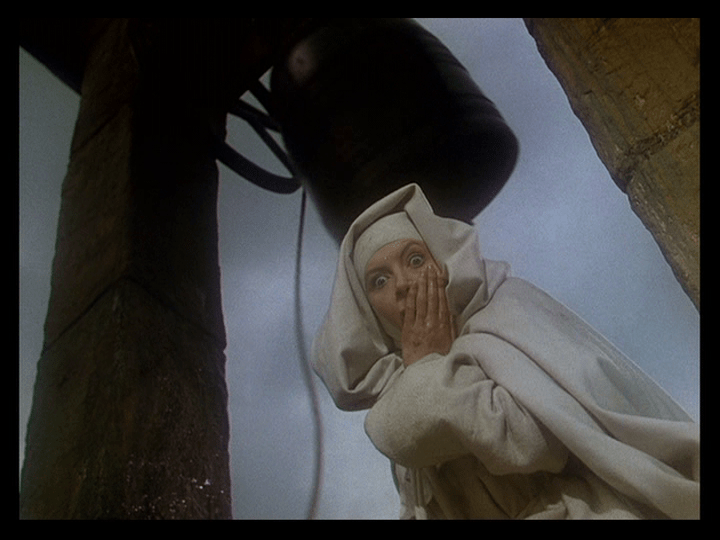

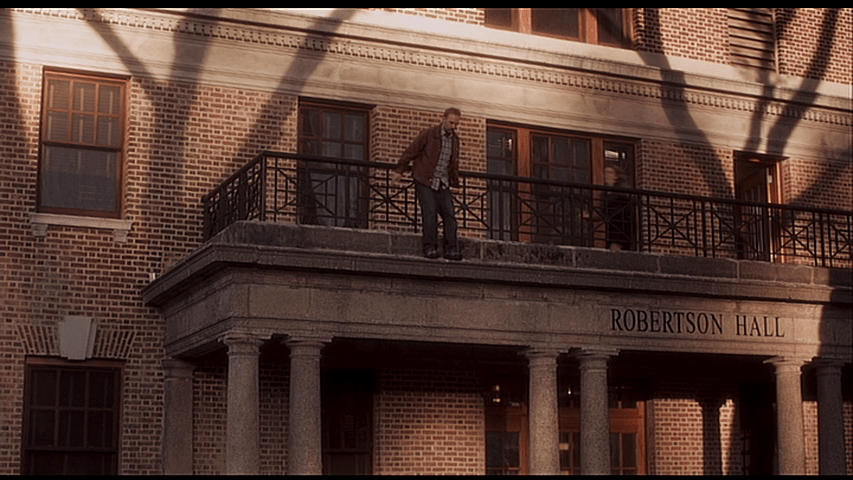

But she appears very soon afterward in corporeal form at Mopu ringing a bell perched at the end of a dizzying abyss which Bertrand Tavernier calls “absolutely breathtaking” in the DVD extra The Audacious Adventurer and an example of special effects that are more impressive than those of the digital era because “these seem to have a soul: they are not just the product of technology but are infused with emotion.”

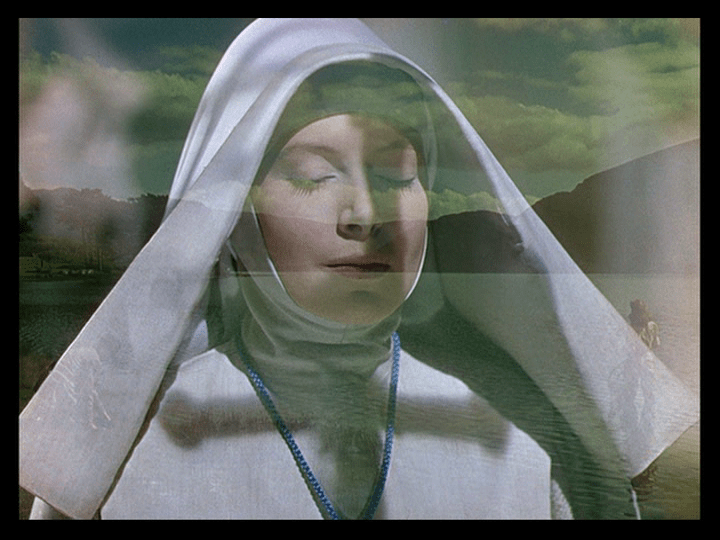

Dave Kehr observes that “despite the great wit and character of [Emeric] Pressburger’s dialogue, Black Narcissus is a film that develops almost entirely through formal rather than dramatic means.” One of my favorite examples of this is the way the past elbows its way into the sisters’ present the longer they remain at Mopu. Early on, Sister Clodagh’s flashbacks are signaled by dissolves, like this one:

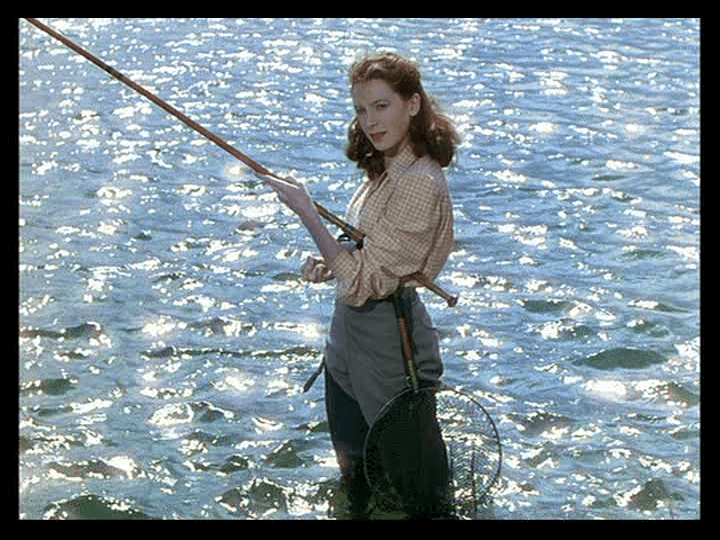

Which is followed by a medium shot of Clodagh fishing amidst a shimmering disco ball of sunlight glistening on the waves that Martin Scorsese accurately lauds in his DVD commentary track as “overwhelming” for those lucky enough to see the film on the big screen in a good print:

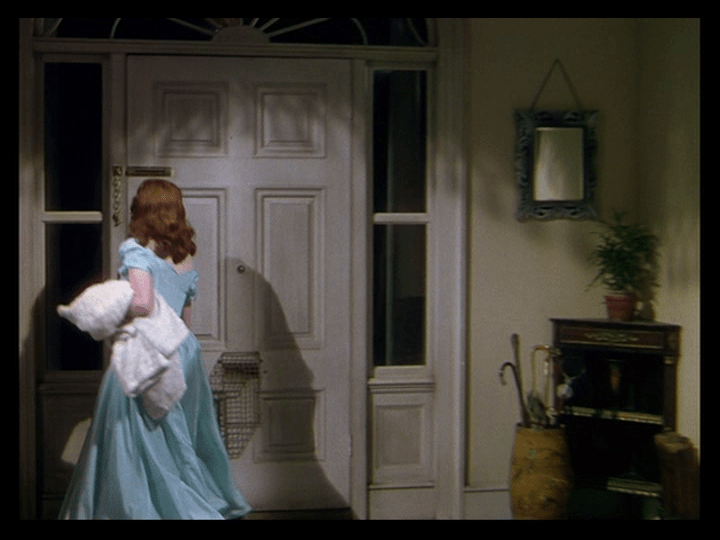

As the film progresses and her memories become as real as whatever she’s experiencing live, though, this is replaced by straight cuts, for instance from Sister Honey’s description of a jacket worn by the Old General’s heir (Sabu) as “just like my grandmother’s footstool” to this one from Sister Clodagh’s youth:

This sequence also ends with an astonishing moment which Ryland Walker Knight describes as transitioning “in one shot from technicolor beauty to the void, the loss of grounding becoming as powerful an edit as imaginable”:

Sister Philippa’s own struggles to combat the return of the repressed are similarly conveyed more by this image of her staring off into space:

And this close-up of her blistered and calloused hands:

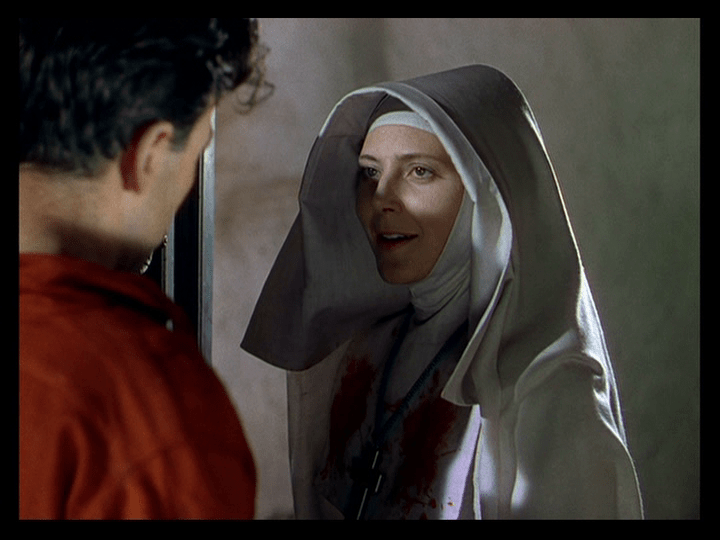

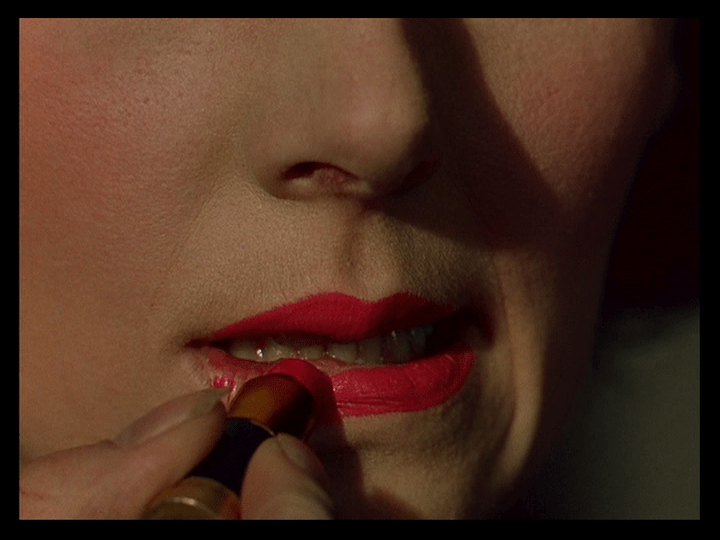

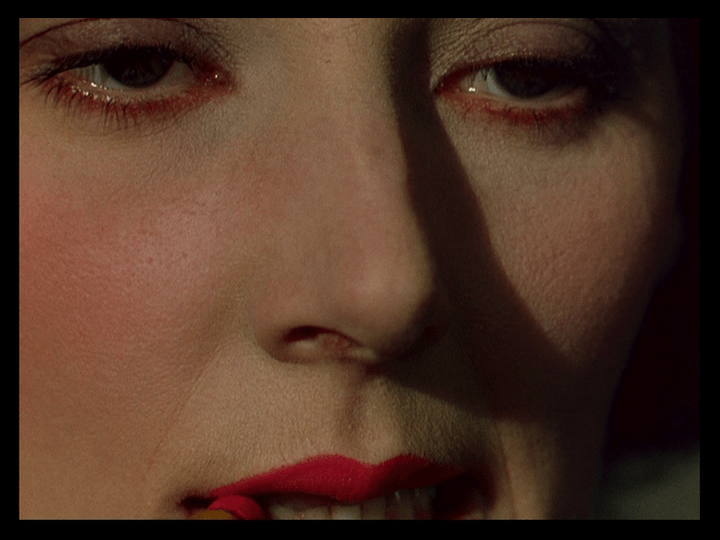

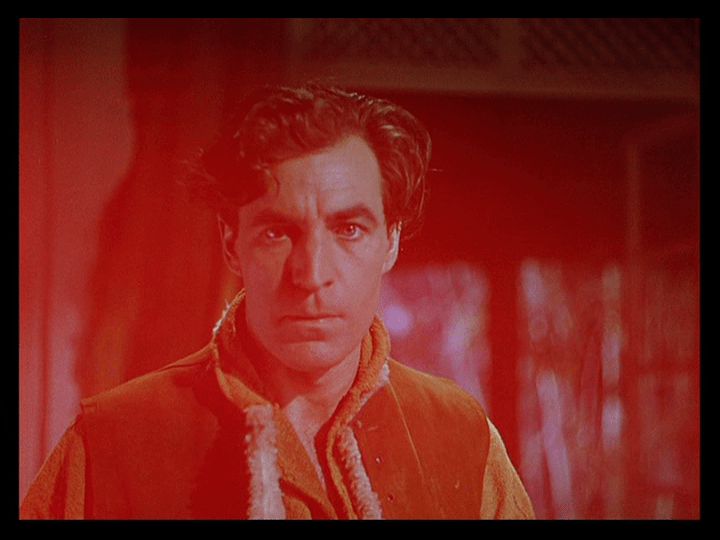

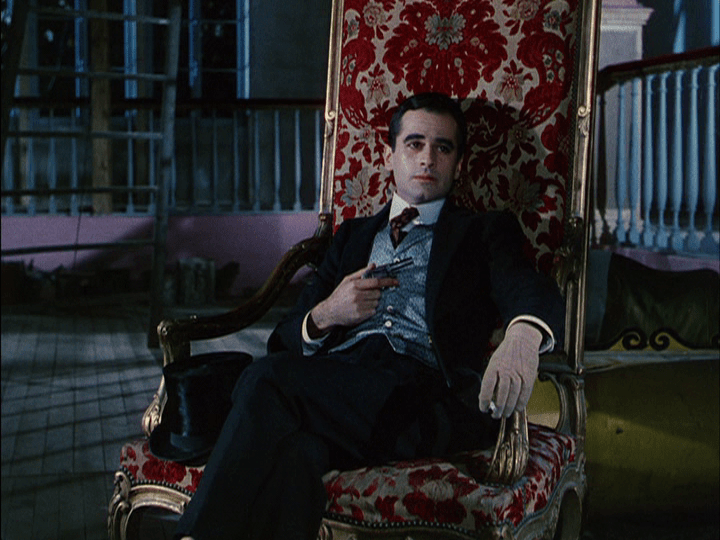

Than anything in the screenplay. But Kehr is right that this tendency is best exemplified in the incredible final sequence, where it’s “enough to see the bright, red lipstick that Sister Ruth has put on to know that the apocalypse is near.” He’s referring to the scene which follows her sudden appearance in a red dress to announce to put an exclamation point on her decision to not renew her vows (the Servants of Mary are only bound to their order for one year at a time):

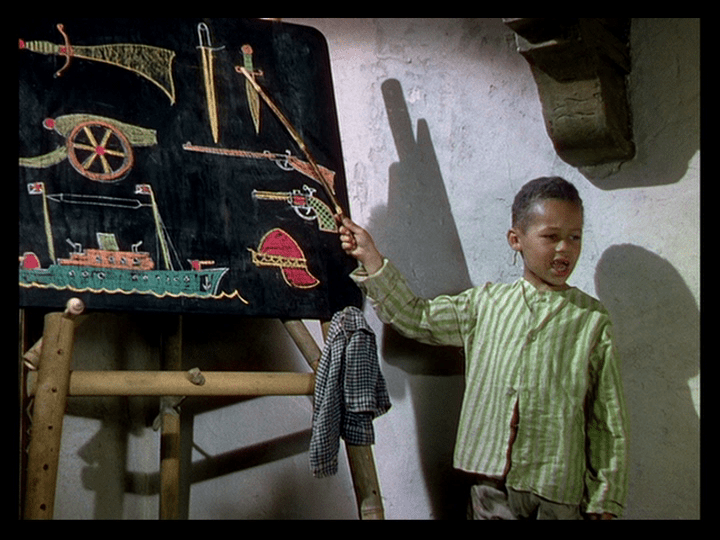

Which was foreshadowed much earlier by a shot of her watching Sister Clodagh speak to Mr. Dean while the convent’s young translator Joseph Anthony (Eddie Whaley Jr.) teaches students how to say the names of various weapons in English:

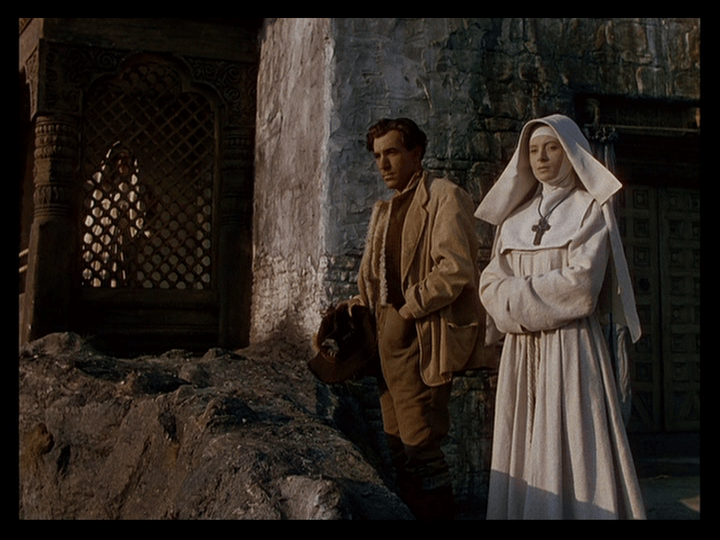

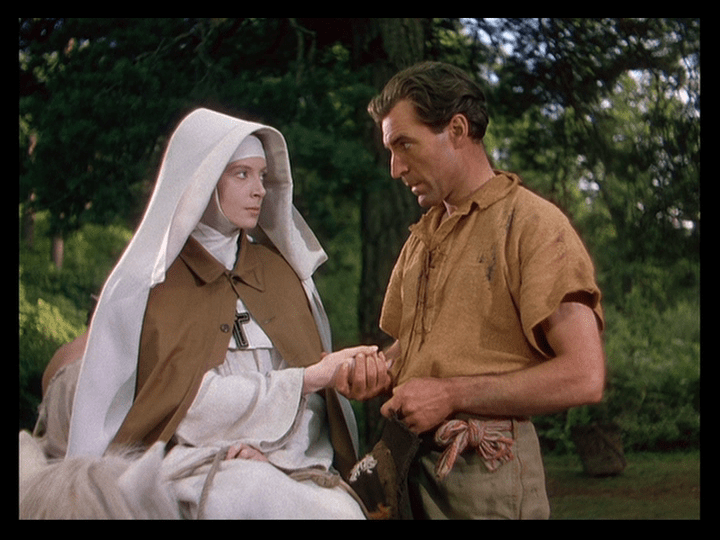

And set up by first a fatal act of attention and kindness by Mr. Dean, who thanks her for her misguided efforts to treat a woman bleeding to death in the convent’s hospital instead of immediately fetching the much more experienced Sister Briony:

And then a fatal decision by Sister Clodagh to ask Joseph Anthony to bring her a glass of milk:

Sister Ruth dumps it out, assuming that it’s poisoned:

And spots Sister Clodagh talking to Mr. Dean once again:

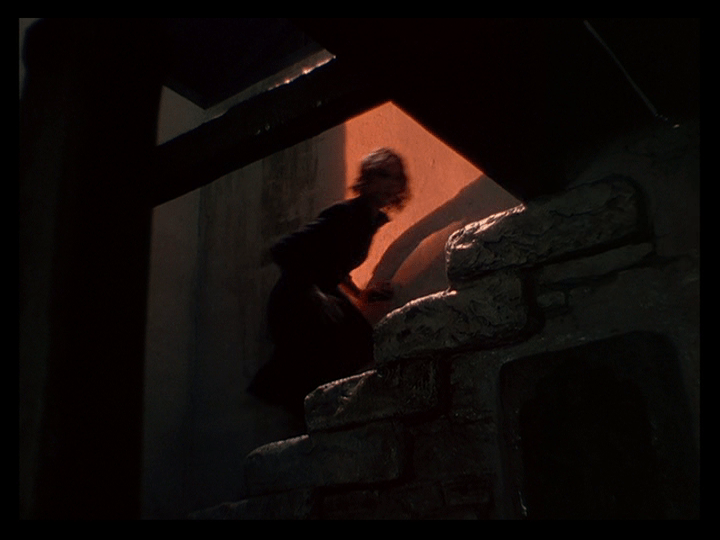

She rushes downstairs past a dramatic streak of sunlight on the floor that Kristin Thompson says in her video essay “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus“ Technicolor technicians lobbied Cardiff to remove from the film after they misidentified it as a lens flare:

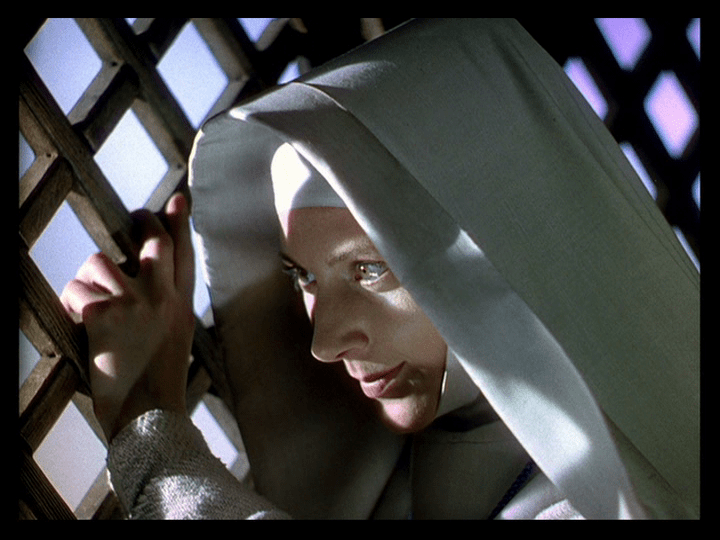

And takes up position behind a window so that she can eavesdrop on them:

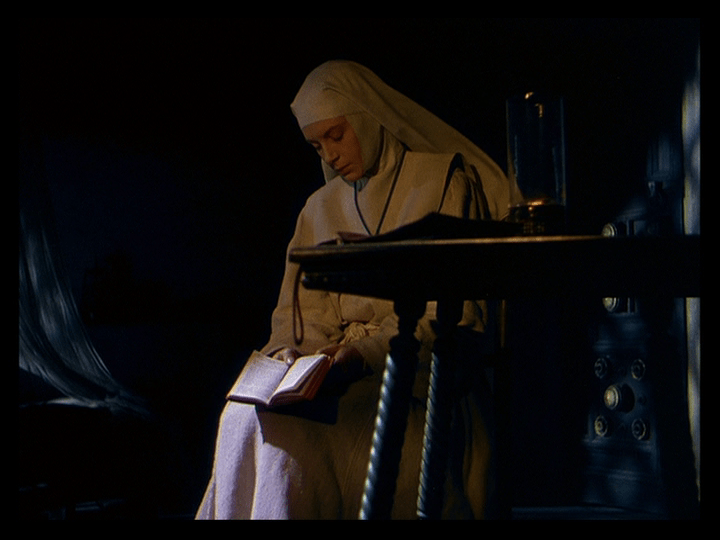

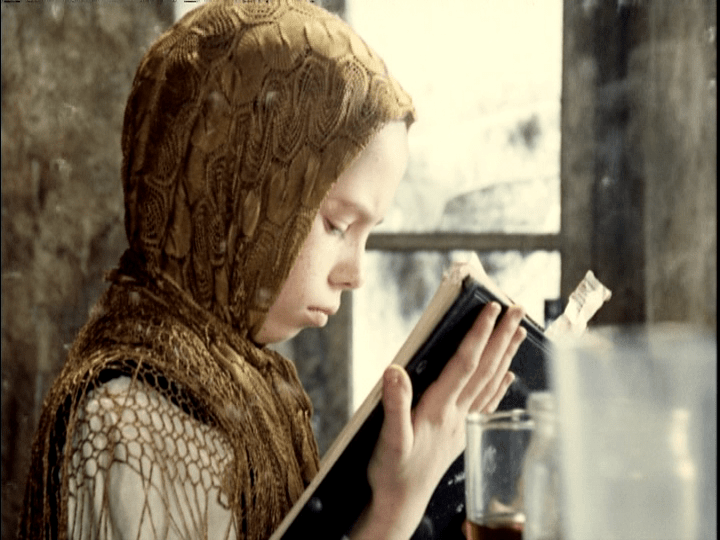

Hearing Mr. Dean console Sister Clodagh leads directly to Sister Ruth donning her red dress. Sister Clodagh implores her to at least wait until morning before departing Saint Faith. And so they settle in for a long night, Sister Ruth with her lipstick and compact and Sister Clodagh with her bible:

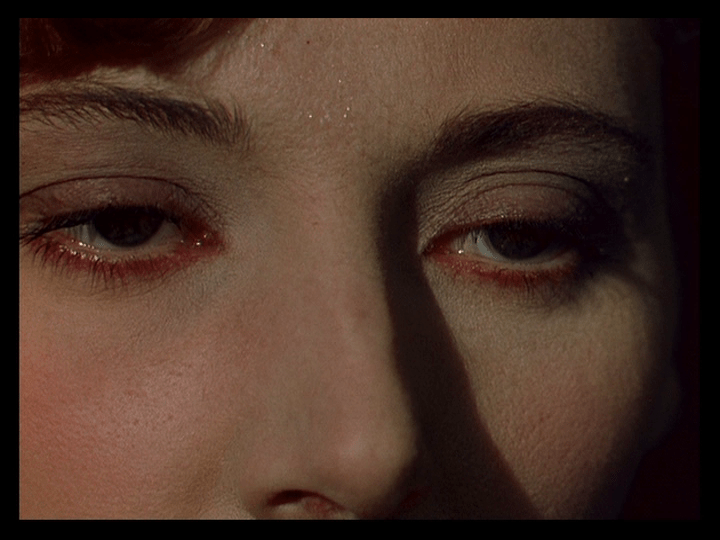

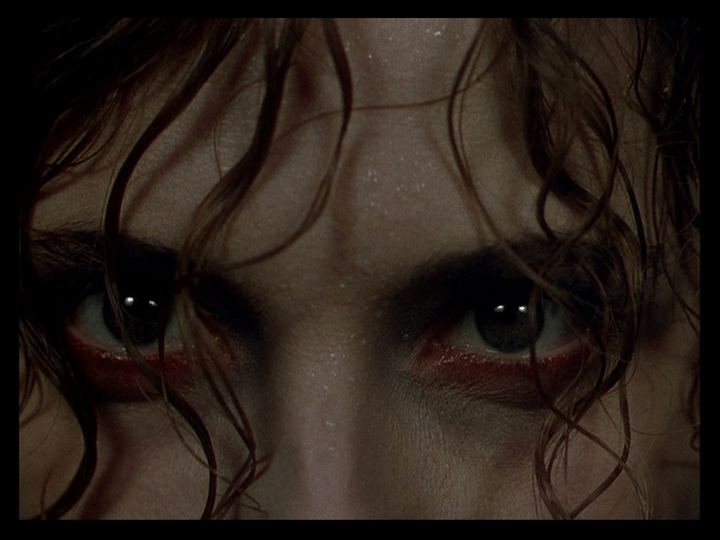

The camera tilts from Sister Ruth’s lips to her red eyes and a forehead dotted with beads of sweat:

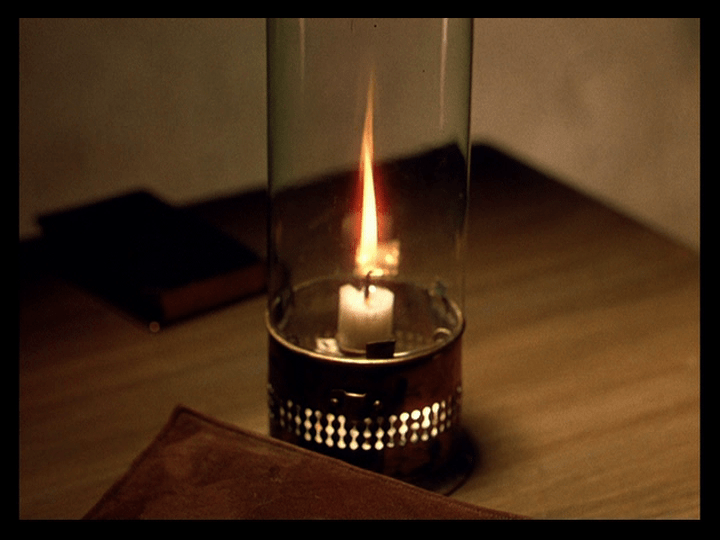

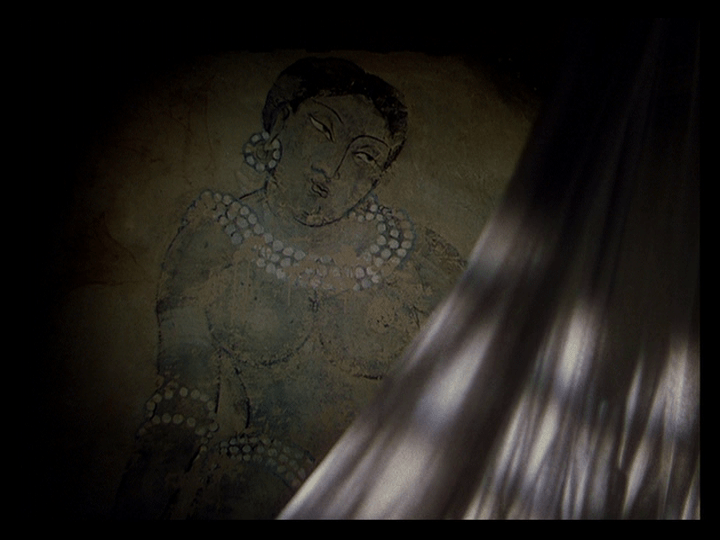

She outlasts Sister Clodagh in a staring contest of sorts in which the passage of time is indicated by cutting back and forth between a shrinking candle and the wall art in Mopu:

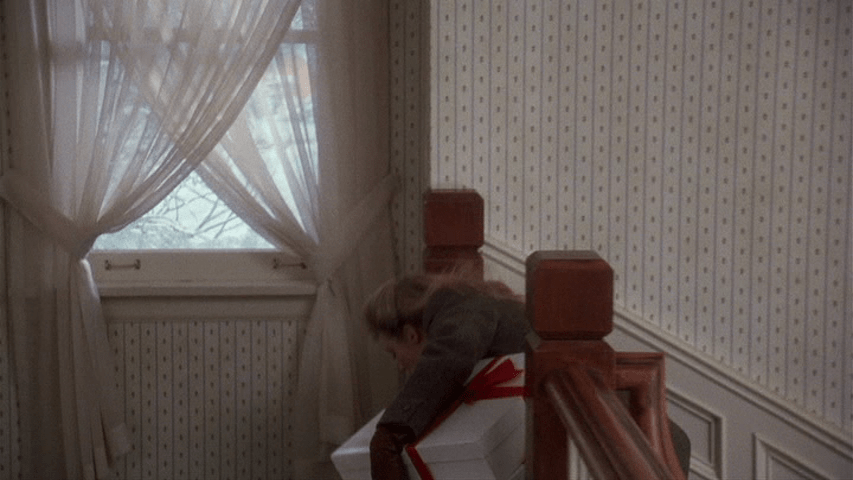

And makes her escape when Sister Clodagh finally succumbs to fatigue:

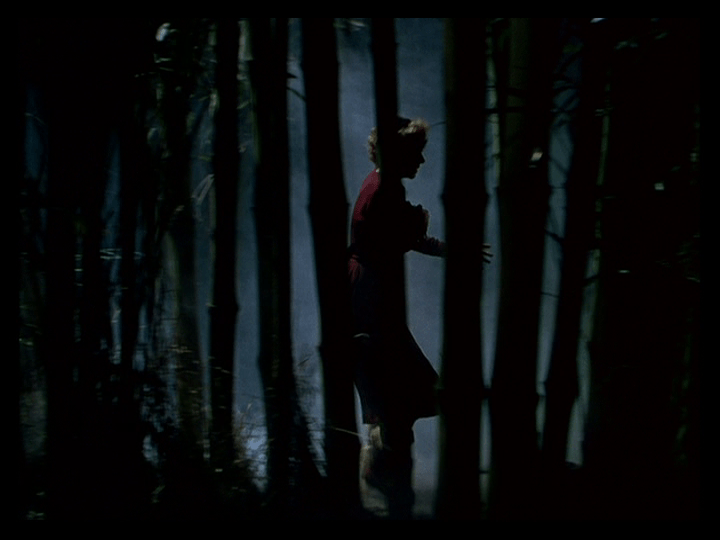

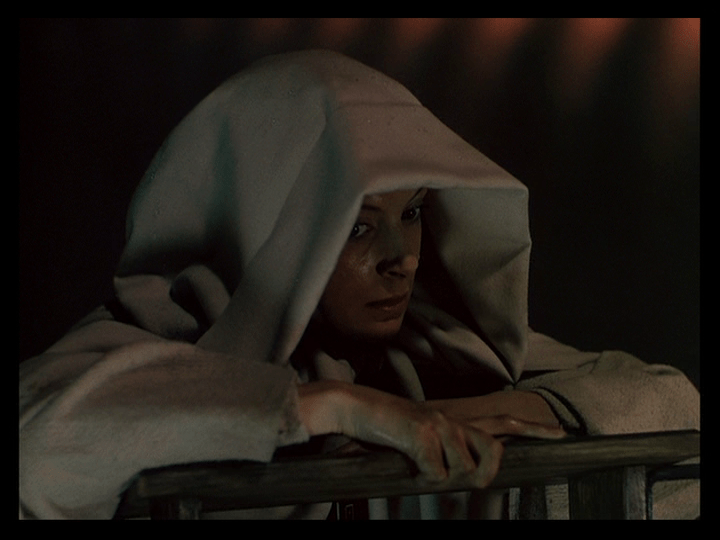

Sister Ruth treks through the jungle in a sequence which contains a shot that reminds me of one in Suspiria that I wrote about in my October, 2022 Drink & a Movie post:

And finally arrives at Mr. Dean’s bungalow, where she tells him she loves him. He rejects her, and she literally sees red and passes out:

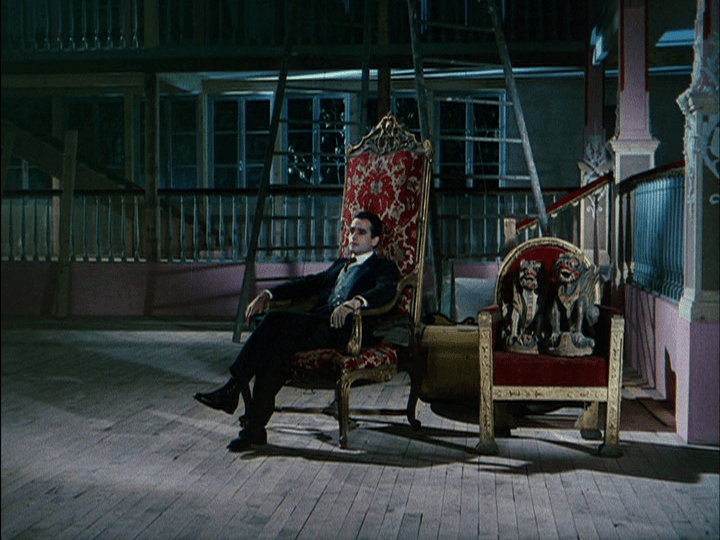

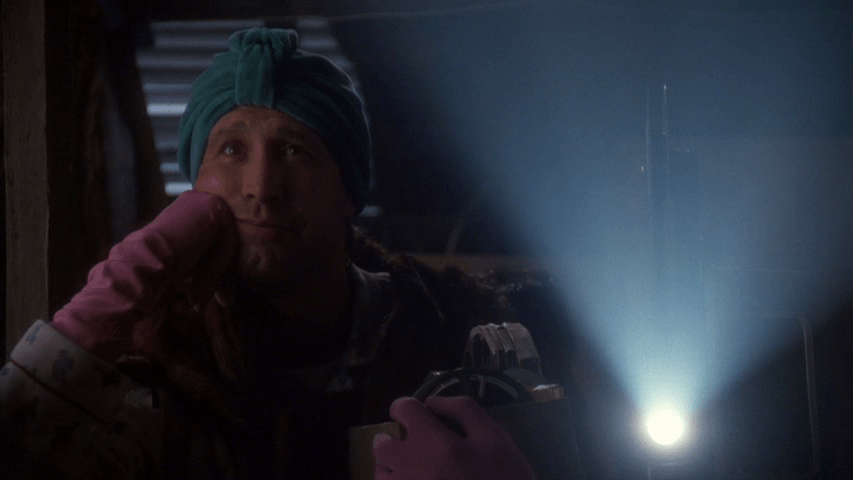

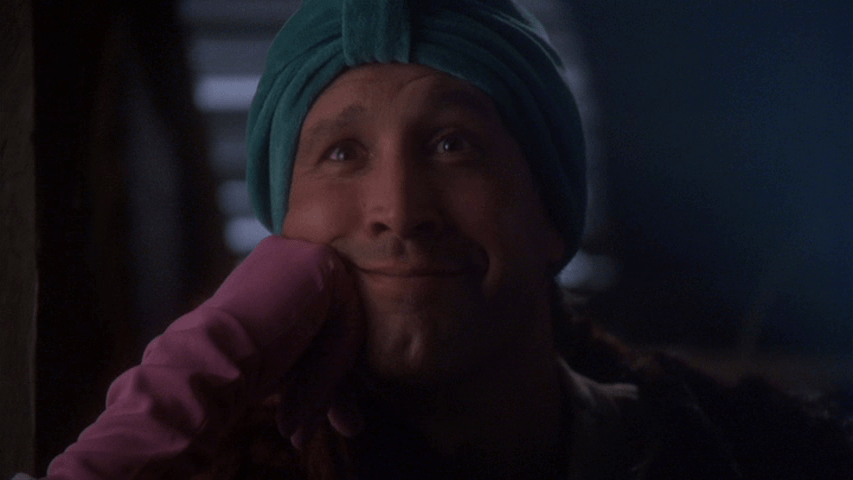

In his autobiography A Life in Movies, director Michael Powell describes the climax of Black Narcissus, which ensues after she comes to and returns to Mopu, as an experiment with “composed film” whereby the blocking and editing were timed to composer Brian Easdale’s music, as opposed to him creating this part of the score based on rushes. Reminiscent of a horror film, it begins with a two shot sequence of Sister Ruth watching Sister Clodagh intently in the predawn hours:

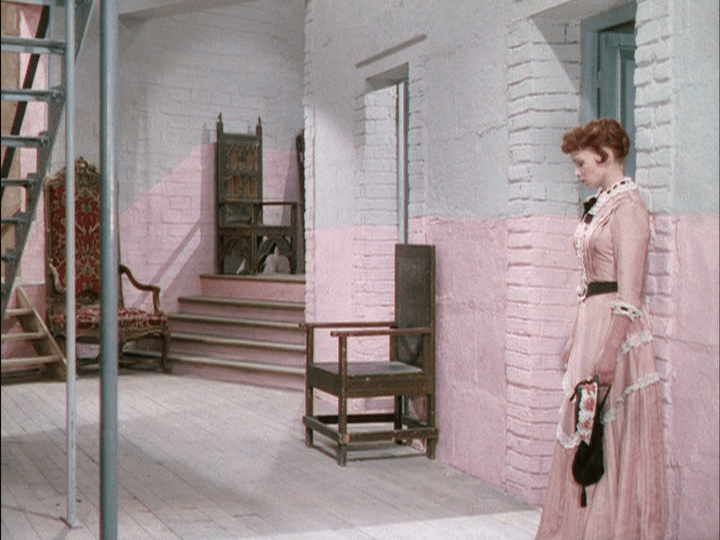

Sister Ruth stalks Sister Clodagh, her presence felt but never seen, as the latter woman attempts to go about a semblance of her morning routine:

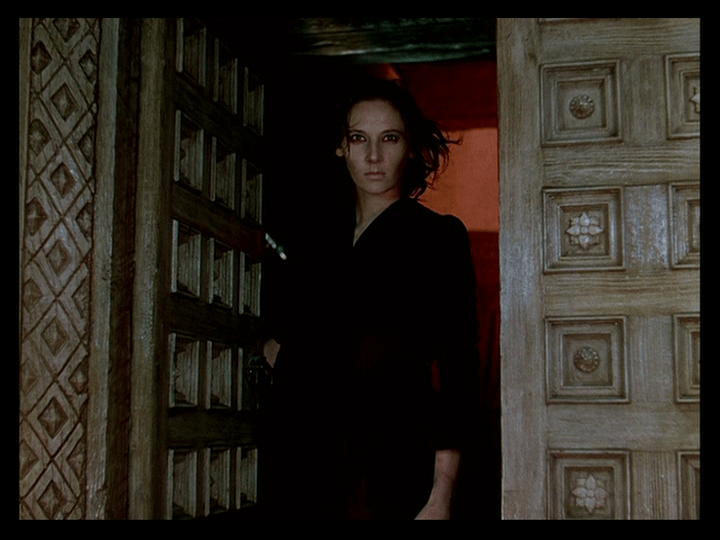

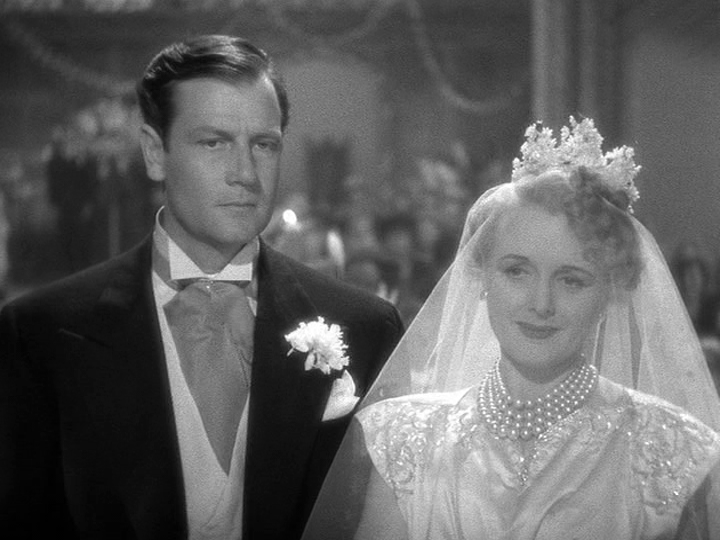

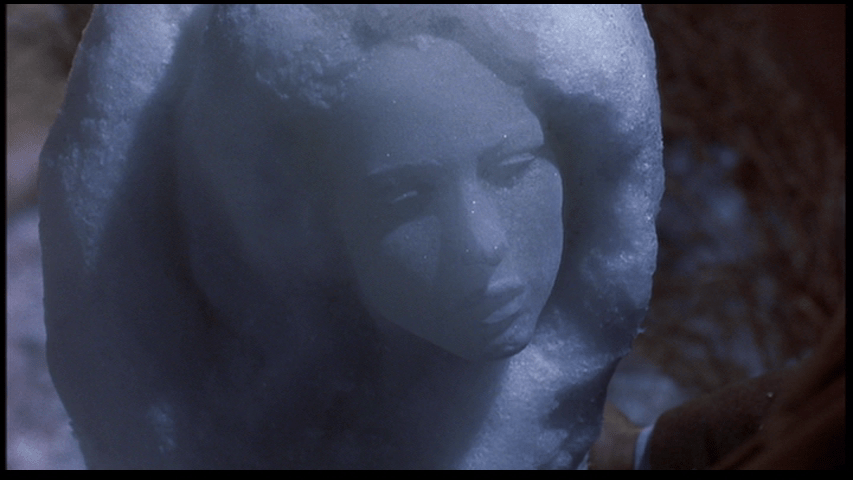

Finally, checking her watch and realizing what time it is, Sister Clodagh steps outside to ring the convent’s bell. This is followed by perhaps the film’s single most famous image:

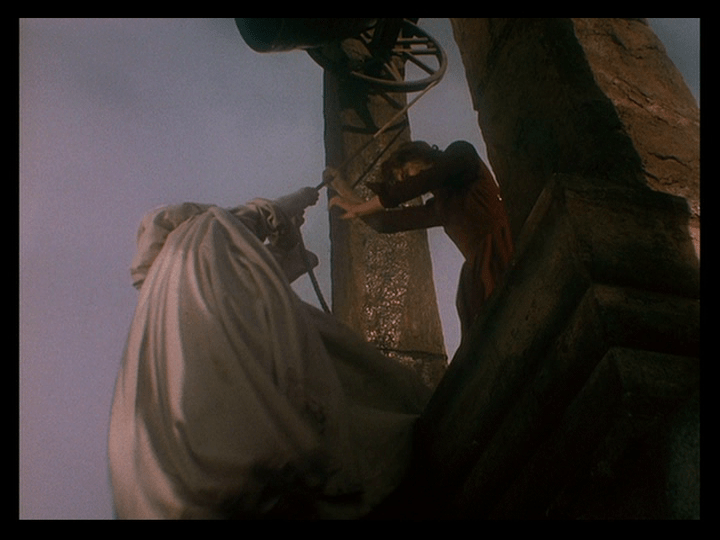

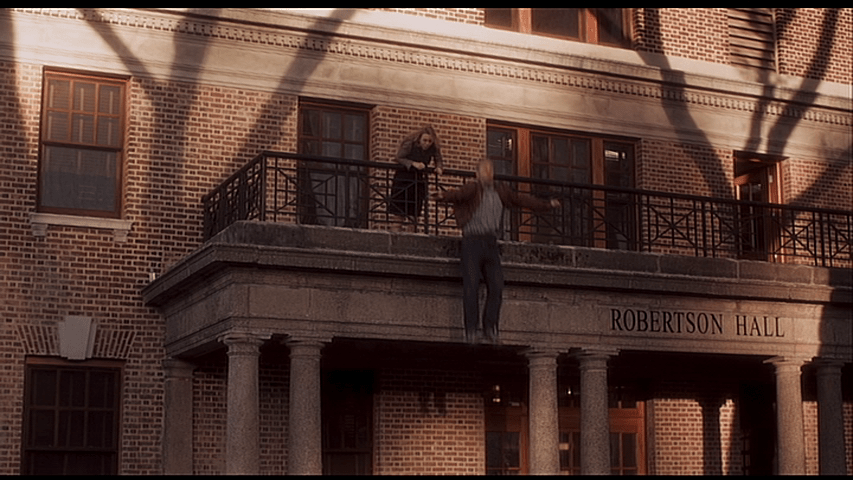

Sister Ruth attempts to push Sister Clodagh over Mopu’s cliffs:

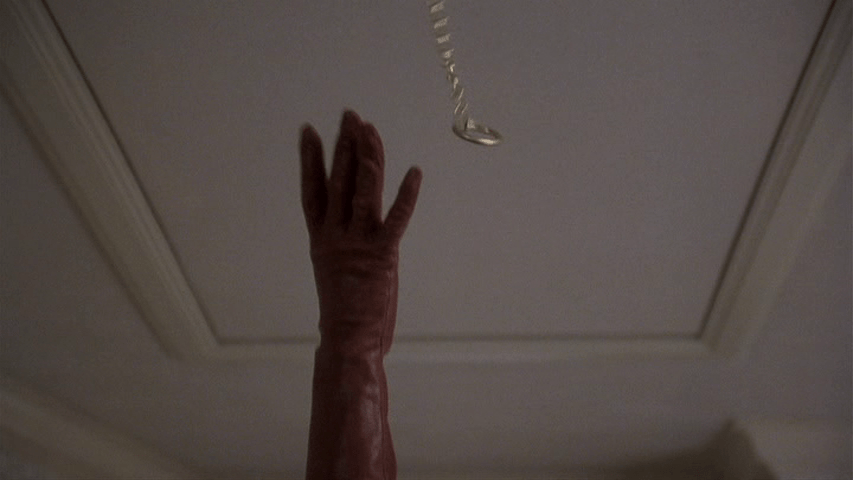

But Sister Clodagh maintains her grip on the bell’s rope:

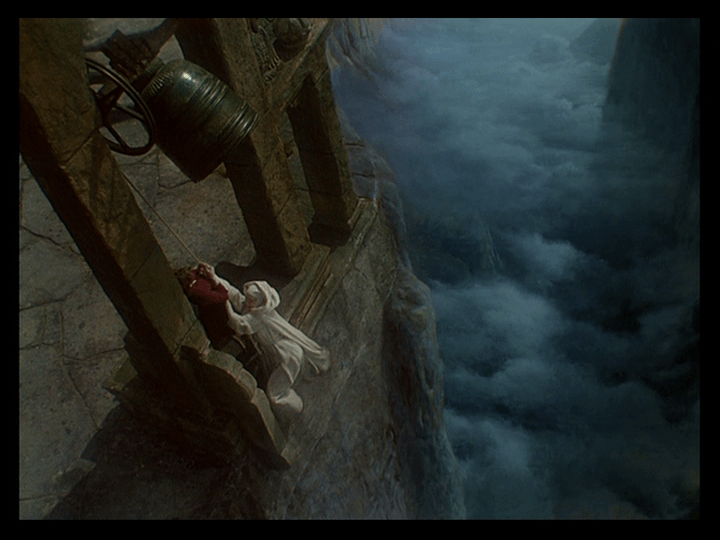

And in the ensuing struggle it is Sister Ruth who ultimately falls to her death:

Kehr notes that India achieved independence mere months after Black Narcissus‘s premiere on April 24, 1947 and suggests that the final images of a procession down from Mopu can be read as anticipating Britain’s departure.

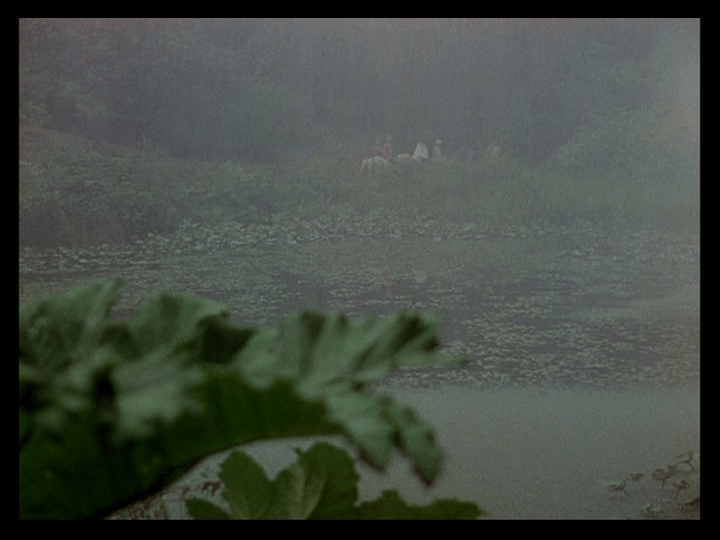

“For Powell and Pressburger,” Kehr writes, “these are not images of defeat, but of a respectful, rational retreat from something that England never owned and never understood. It is the tribute paid by west to east, full of fear and gratitude.” This reading is complicated for me by the fact that the film doesn’t end with Sister Clodagh looking back at Mopu as it’s covered by mist:

But rather with Mr. Dean bidding a tender farewell to her:

The rains beginning to fall, proving his prediction that the sisters wouldn’t last this long correct:

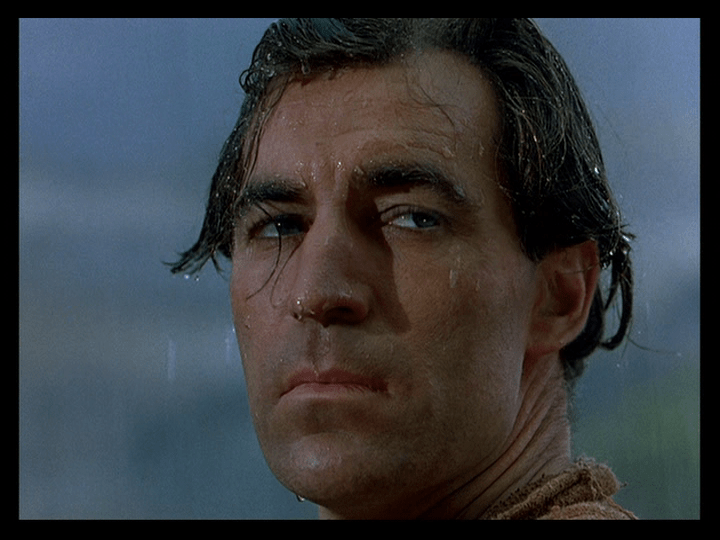

And finally him looking on as they ride away:

So, yes, the last image is of a British retreat, but it’s a POV shot from the perspective of an Englishman who will remain behind and who promises to take care of Sister Ruth’s grave. It therefore doesn’t play as a farewell to Empire for me so much as an elegy for a certain idea of Britishness, one caught impossibly between the two ways of living in a colonized land previously articulated by Sister Philippa: “either you must live like Mr. Dean, or . . . or like the holy man. Either ignore it or give yourself up to it.” Sister Clodagh intuits that there must be a third way, but cannot articulate what it is, which is why she and the surviving sisters must leave. It’s also why, for all of Black Narcissus‘s gorgeous and inspired cinematography, my favorite moment of all might be the simple scene in which Sister Philippa places the flowers she planted instead of vegetables like she was supposed to on Sister Ruth’s grave:

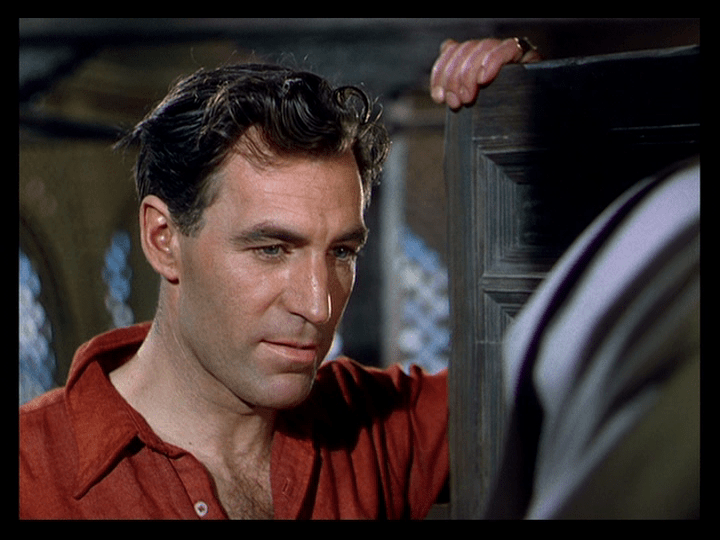

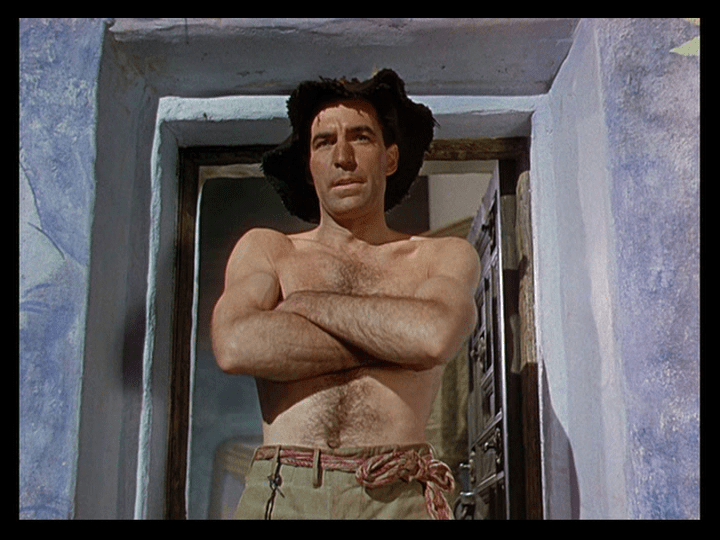

Here, more than the film’s actual final images, is the respect, fear, and gratitude that Kehr speaks of, as well as, appropriately, sadness. Which is too somber of a note to end a post in this particular series on, so here’s a shot of a shirtless Mr. Dean:

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka my loving wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.