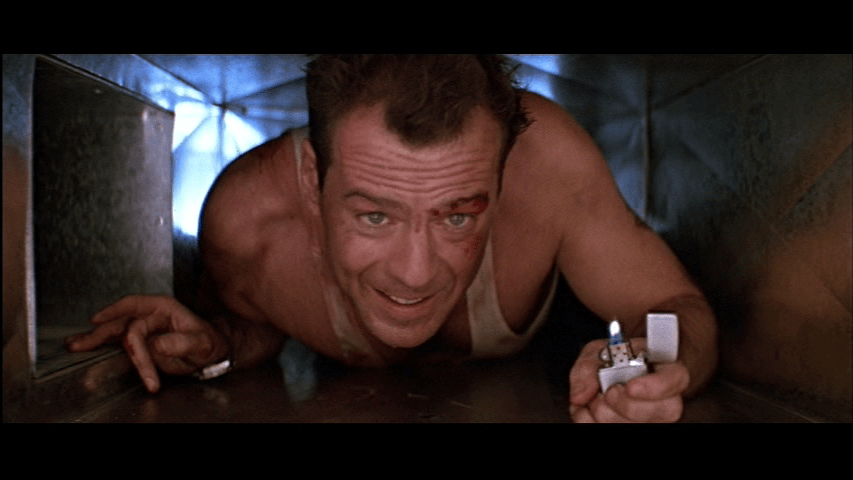

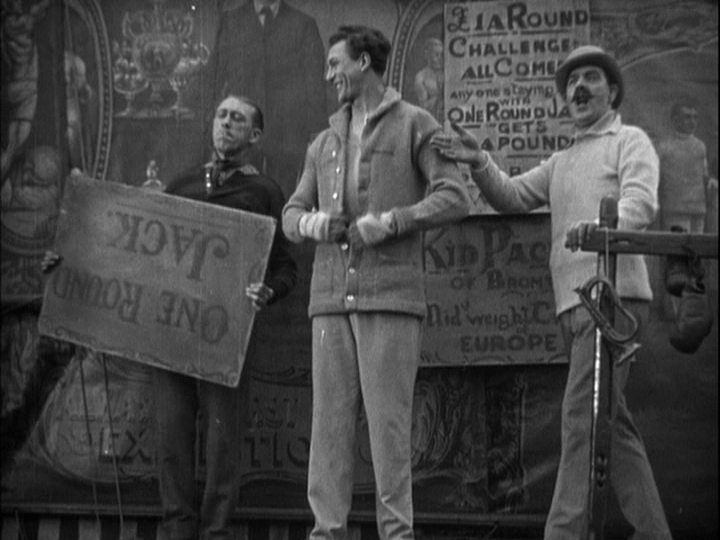

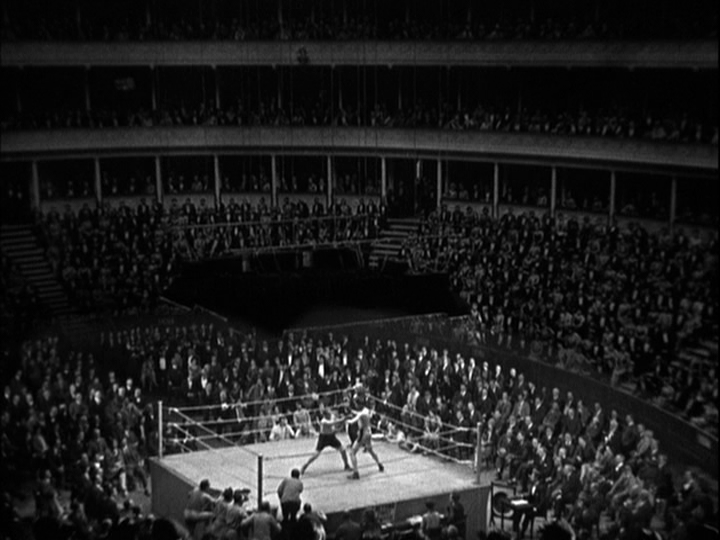

I started this series four years ago as a way to get back into the habit of regular writing. It proved to be so effective that by July I had made up my mind to keep it going through 2025 and supplement it with enough “bonus” posts to give me the equivalent of a year-long weekly film series. Eventually it occurred to me that if I added one more, I could edit everything into a self-published book complete with an introduction, and when I created a two-column landing page a 54th became inevitable. But now after 95,940 words and 1,746 screengrabs, we have finally reached the finish line! We end as we must with the most canonical drink I haven’t yet written about, the Martini. I’m pairing it with The Thin Man and the screen couple who may well be responsible for James Bond’s outdated impression that it’s supposed to be shaken instead of stirred, Nick (William Powell) and Nora (Myrna Loy) Charles. After all, that’s how Nick is preparing one when we first meet him at the end of a 50-second-long tracking shot that makes its way through a crowded dance floor before coming to rest on our hero:

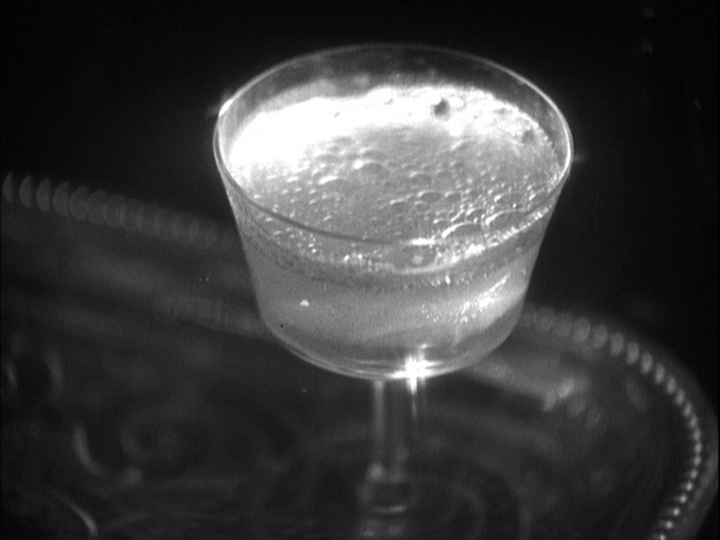

“You should always have rhythm in your shaking,” he tells the bartenders who watch him, rapt. “Now, a Manhattan you shake to foxtrot time.” He begins to strain the concoction into a glass:

“A Bronx to two-step time,” he continues, placing the drink on a tray:

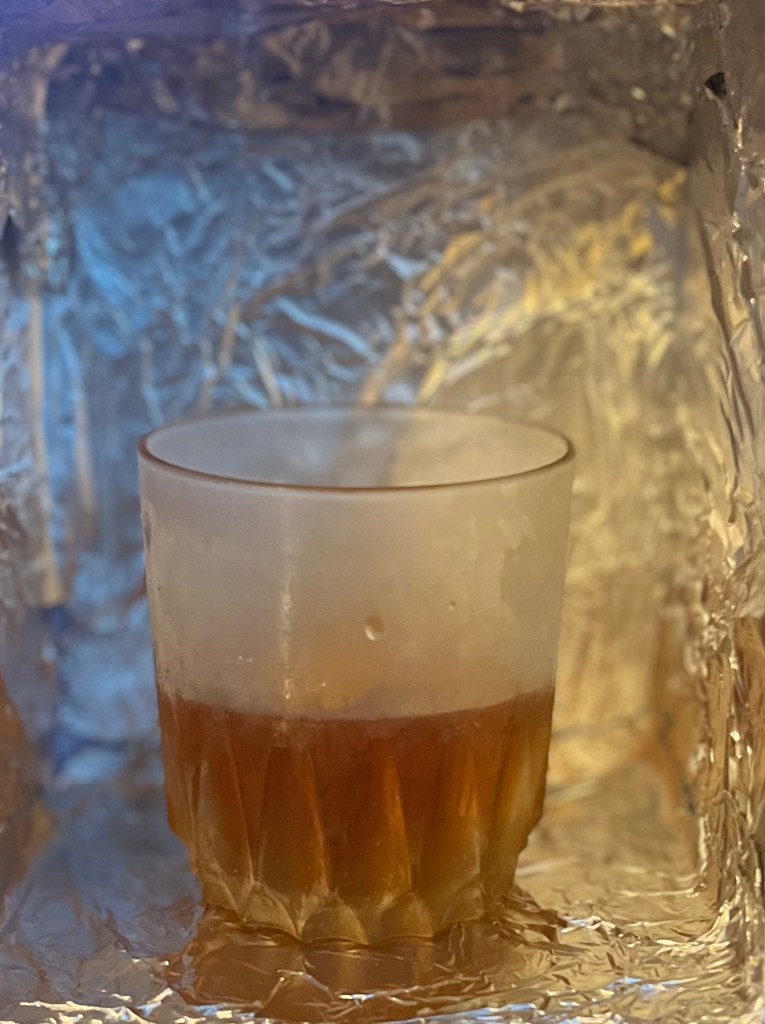

“The dry Martini you always shake to waltz time,” he concludes. Which: this *would* guarantee that the shaking is done gently, limiting aeration and dilution to acceptable levels, and I don’t think a barspoon is capable of anywhere near the same degree of bespoke sophistication, so maybe the technique is overdue for a revival! The Martini proportions in The PDT Cocktail Book are perfect as far as I’m concerned, but in a nod to the Christmas season (which is when The Thin Man takes place) we’ve been making ours with a dash of an extra ingredient and a festive garnish. Here’s how:

3 ozs. Plymouth gin

1 oz. Dolin dry vermouth

2 tsp. Élixir Végétal de la Grande-Chartreuse

Stir all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled Nick & Nora (of course!) glass. Garnish with three fermented Christmas cranberries on a cocktail pick.

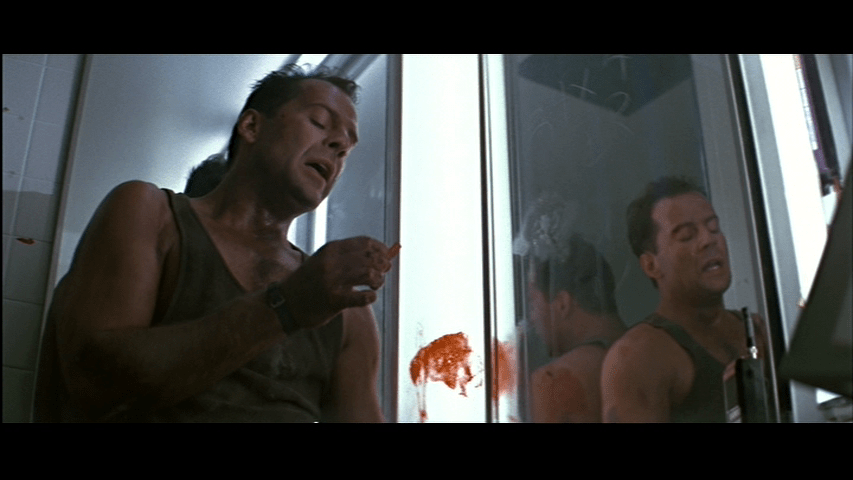

Élixir Végétal de la Grande-Chartreuse is the original product that its more famous descendants green and yellow Chartreuse are based on and a little goes a very long way. Here it contributes distinctive herbal notes to the nose and sip and, just as important for our purposes, a pale but pronounced green color that contrasts beautifully with the brick red garnish. The cranberries, in turn, provide just the slightest bit of effervescence, which accentuate the citrus notes of the Plymouth, but fear not: everyone we’ve served this to agrees that the little surprises we’ve added know their place and that our version has the classic finish of the one Nick proceeds to serve himself:

And savor:

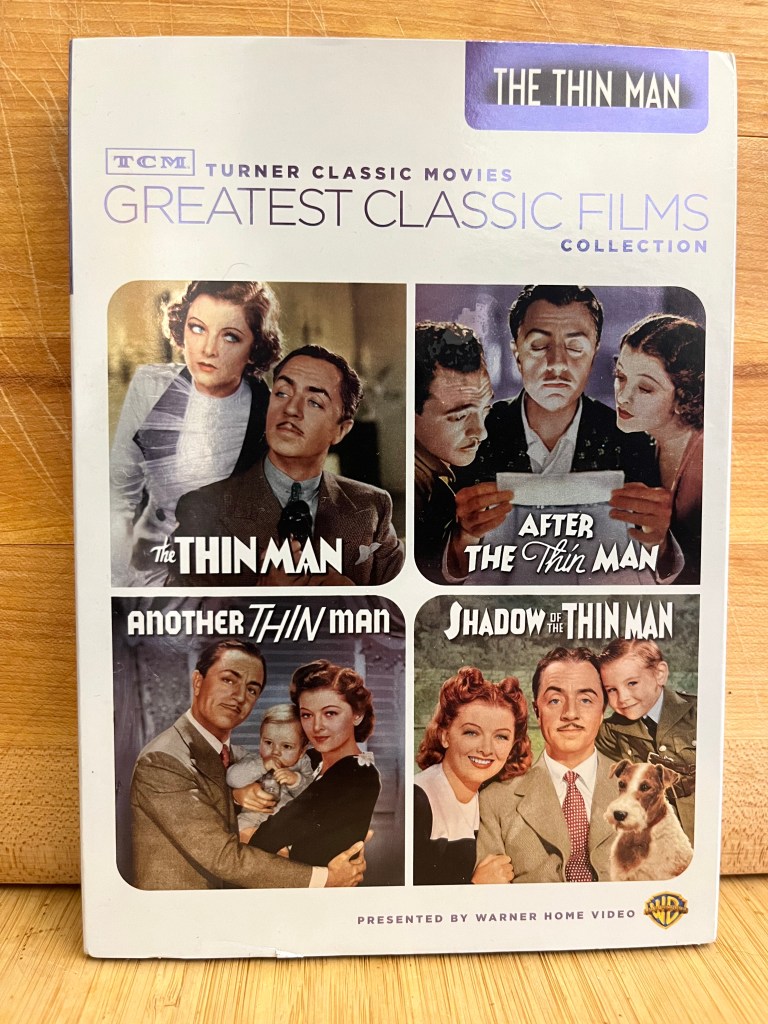

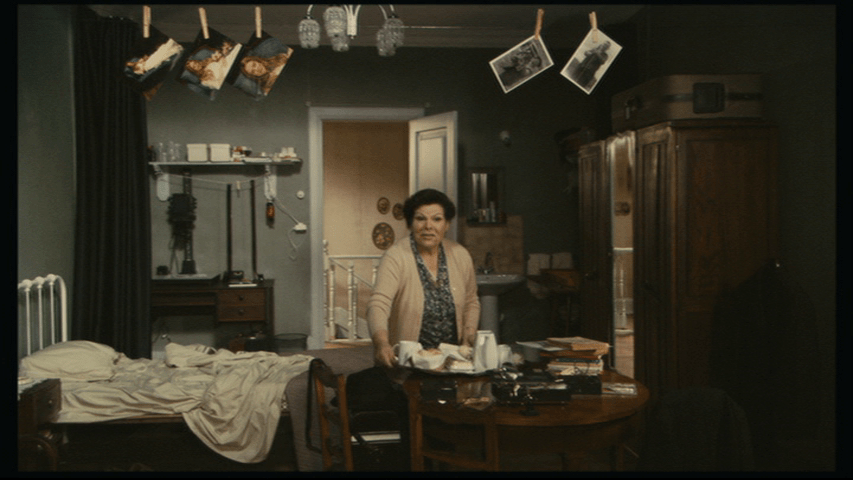

The images in this post all come from my TCM Greatest Classic Films Collection box set which includes the first three Thin Man sequels, too:

The original can also be streamed on Tubi for free if you don’t mind commercial breaks or rented and purchased from a variety of platforms if you do.

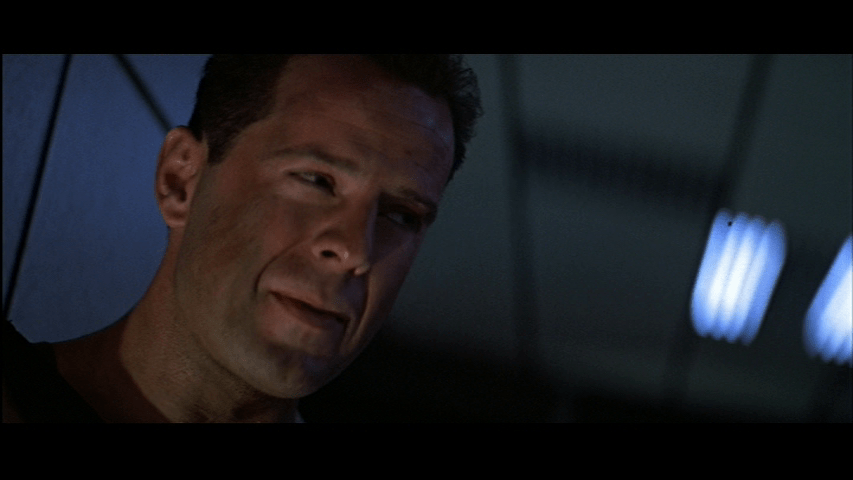

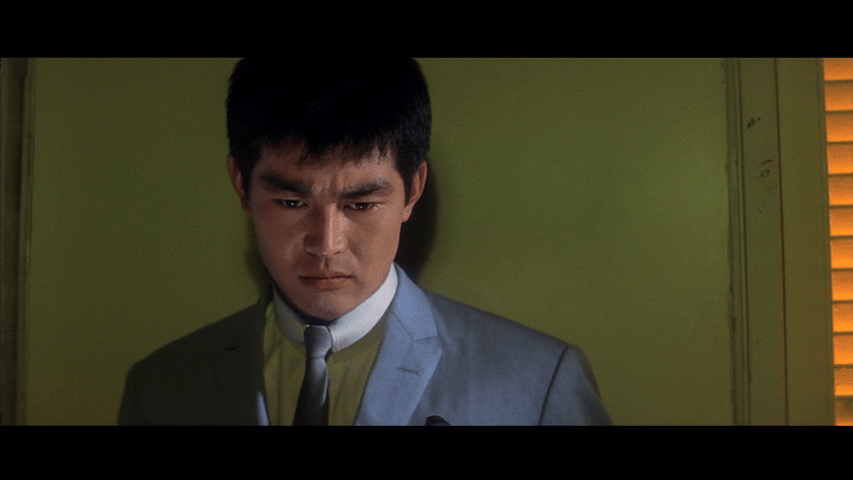

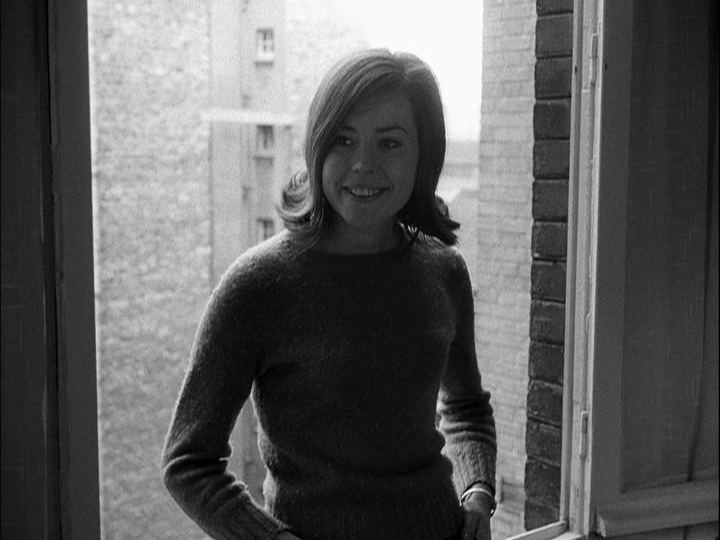

Martha Nochimson argues in her book Screen Couple Chemistry: The Power of 2 that The Thin Man “is not structured by Hollywood’s familiar gender formula: woman/body–man/mind.” She submits as evidence the fact that both Nick and Nora first appear from behind, him in the mixing ritual depicted above which “requires an atypical male absorption in his body,” while her entrance behind their dog Asta “uses the cliche of female closeness to animality and body to make a joke of Hollywood’s traditional images of female glamour”:

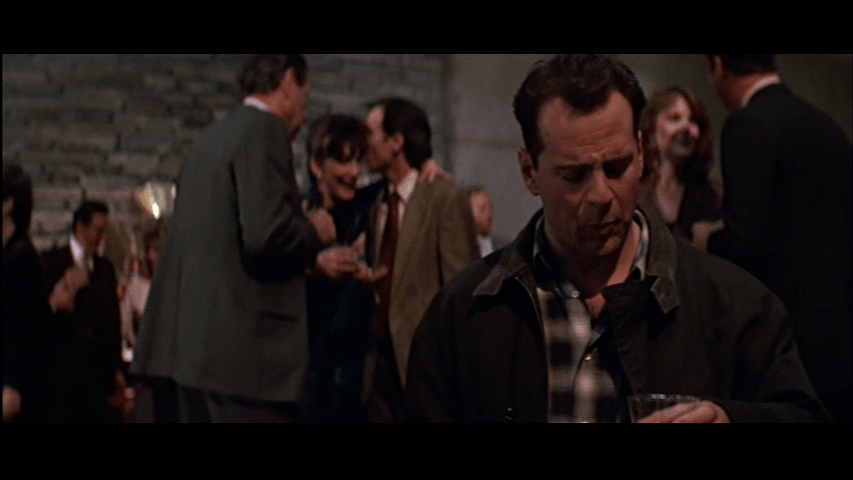

As Rob Kozlowski describes it in his book Becoming Nick and Nora, their first conversation “takes place over the course of a single, forty-seven-second shot” that has nothing to do with the murder mystery that the film is ostensibly about “but everything to do with showing us this marvelous relationship.” It is preceded by Nick, who is visibly but amiably tipsy throughout this scene and much of the movie, forgetting the word “cocktail” but still managing to make himself understood to a waiter as he invites Nora to sit down and join him in one:

The long take which follows is, per Kozlowski, “very economical,” but also “absolutely the correct approach from a narrative standpoint”:

Because:

By holding both Nick and Nora in the frame, we’re able to see them both speaking, and both listening, at the same time. Nora, adorned in a fur coat with her chin resting in her hand, perpetually amused by the sight of her besotted and blotto husband, has her focus entirely on him. Nick, with his arms resting on the table, his hands inches away from hers, has his focus entirely on her.”

The scene ends with Nora asking Nick how many he has had. “Six martinis,” he replies. Her response is to immediately order five more to catch up, which to Kozlowski captures the essence of what makes theirs “the friendliest, most fun marriage ever captured on screen.”

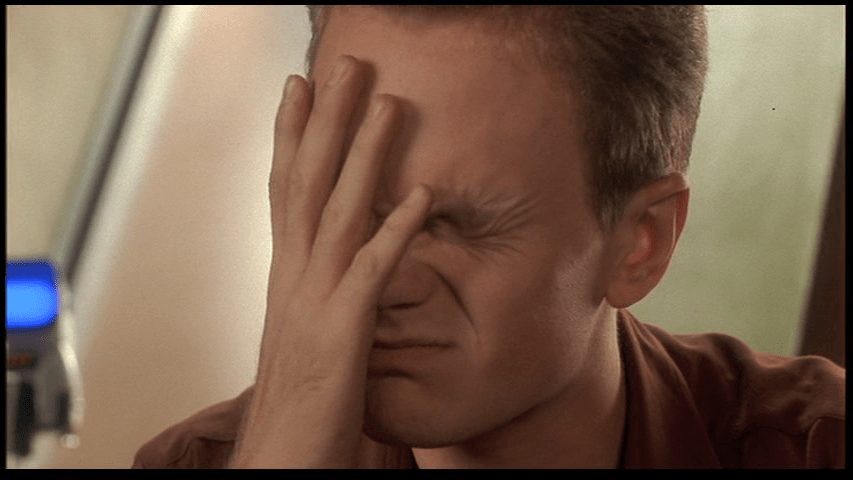

“They’re almost always playing,” he explains, “and they’re equals on top of it all.” Nochimson agrees with him about this sequence, which she calls paradoxically “both archly witty and genuinely earthy,” but also notes that while “time has veiled Nick and Nora in sentimental nostalgia,” upon closer inspection “their abrasive qualities burst off the screen.” In a not-quite-but-almost-acknowledgement of the darker side of drinking, the latter wakes up the following morning with a hangover (instead of alcohol poisoning, which might be more realistic), but rather than make her more relatable, the ice bag she wears like an elegant hat only serves to reinforce Nochimson’s description of her as “tall, slim, condescending, and always appareled in stunning, regal, intricately designed and infuriating (for those in the audience who will never be able to afford such things) ‘outfits'” who “stands with that ramrod carriage that summons images of young girls schooled relentlessly in balancing books on their heads”:

Meanwhile Nick, whose speech is already beginning to slur from what appears to be a breakfast of Scotch and soda, does indeed have “the loose-jointed bearing of a man just about to fall into a heap” as he first flicks her nose:

Then pantomimes smacking her in retribution for a well-deserved slap on the back of the head:

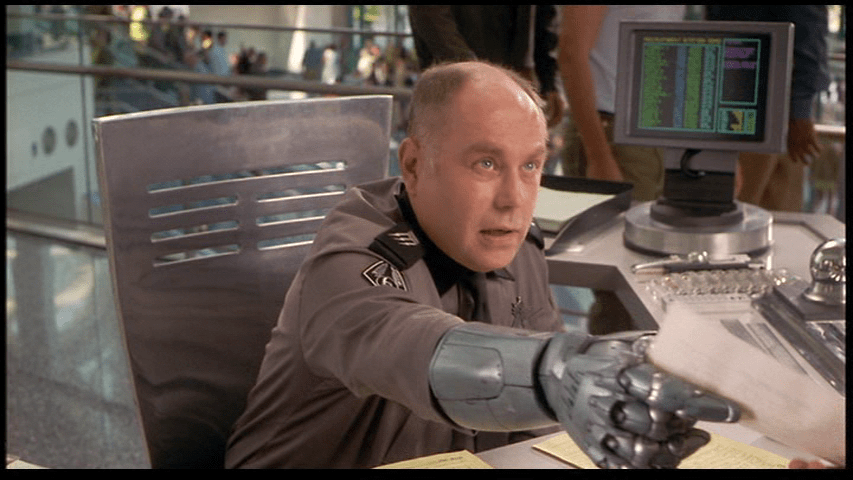

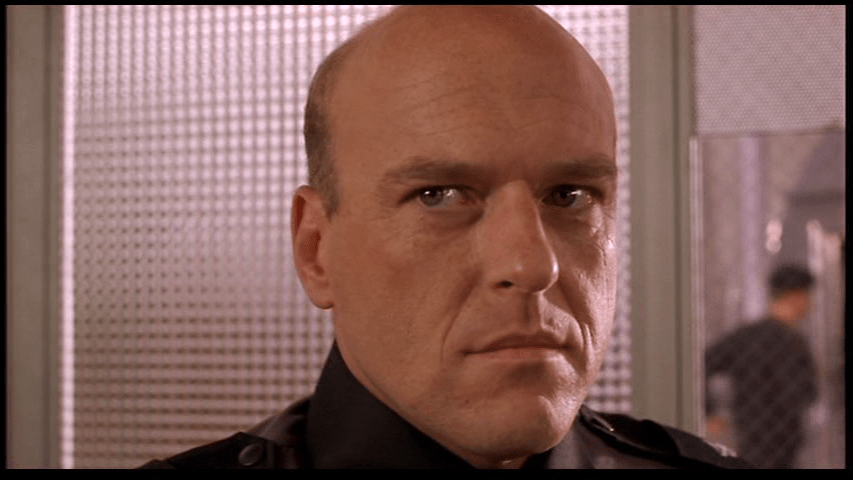

The man on the phone in the foreground is Herbert MacCaulay (Porter Hall), lawyer to inventor Clyde Wynant (Edward Ellis), who we see here working in his laboratory:

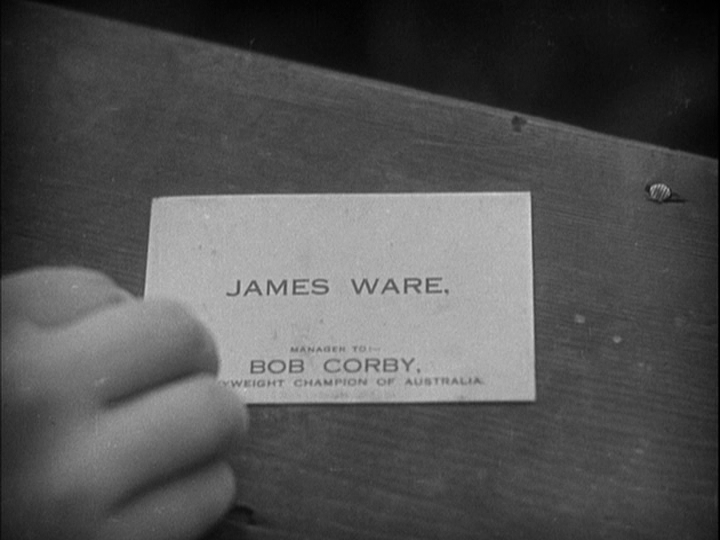

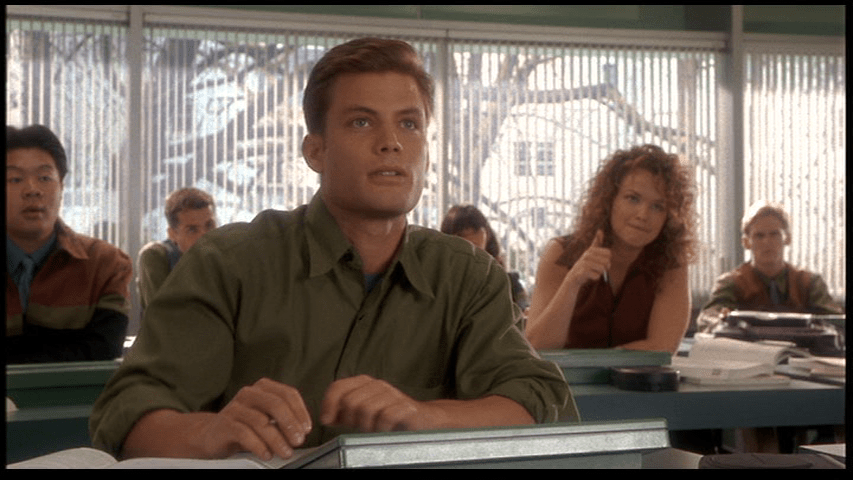

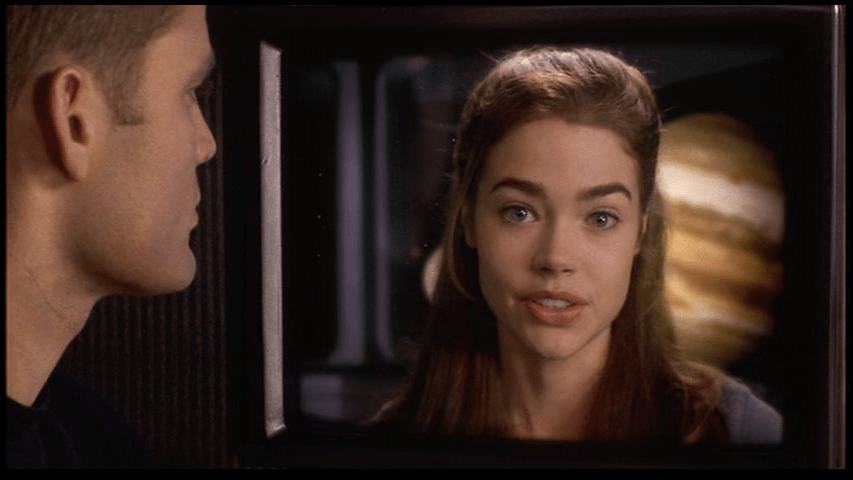

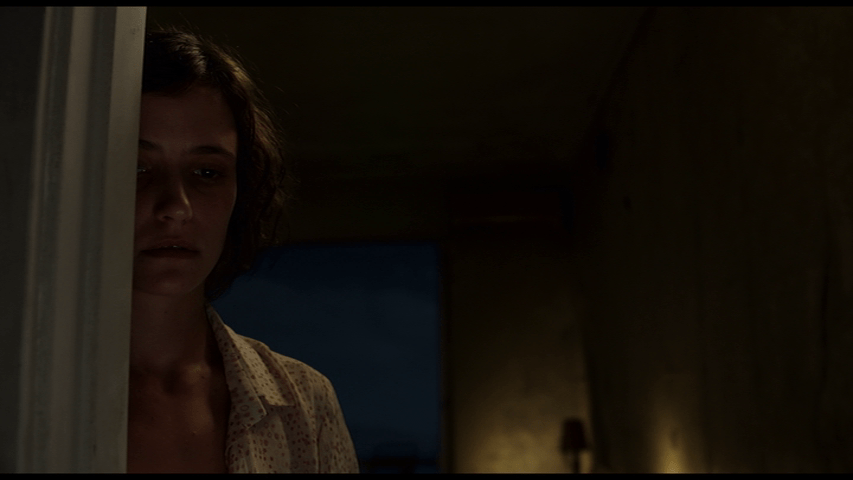

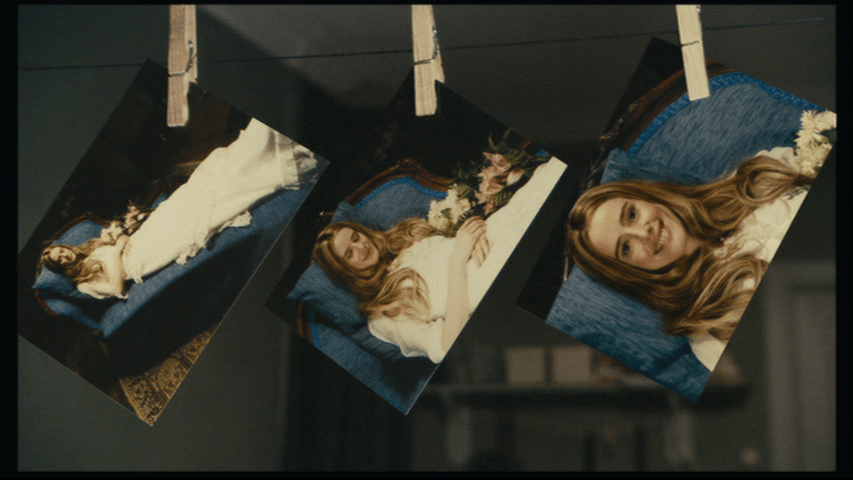

And the mixology lesson we started this post with was interrupted by Wynant’s daughter Dorothy (Maureen O’Sullivan), who remembers Nick, a former private detective, from a case he worked on for her father in her youth:

You see, Clyde has disappeared. Or maybe he hasn’t: the phone call MacCaulay takes informs him that Wynant is back in town and wants to meet. Except that Wynant doesn’t show, and in the meantime his secretary-cum-mistress Julia Wolf (Natalie Moorhead) turns up dead. Coincidentally, she had just agreed to meet Wynant’s ex-wife Mimi Jorgenson (Minna Gombell), Dorothy’s mother, who upon discovering the body first screams:

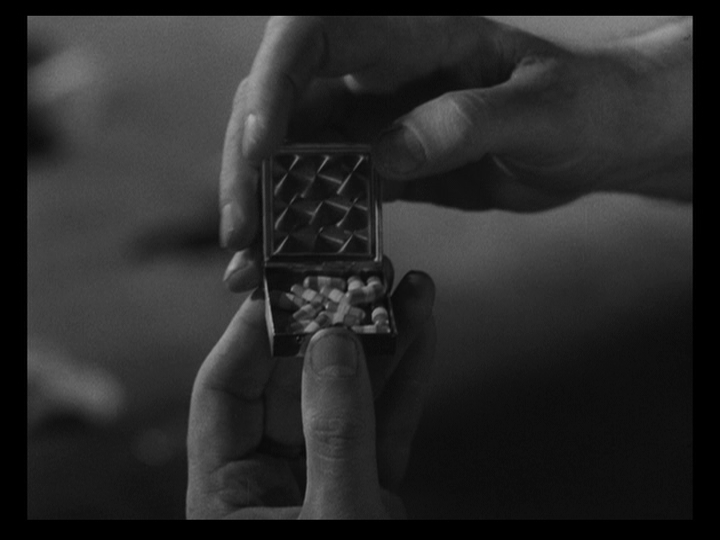

But then makes a face and leans forward to remove something from the crime scene:

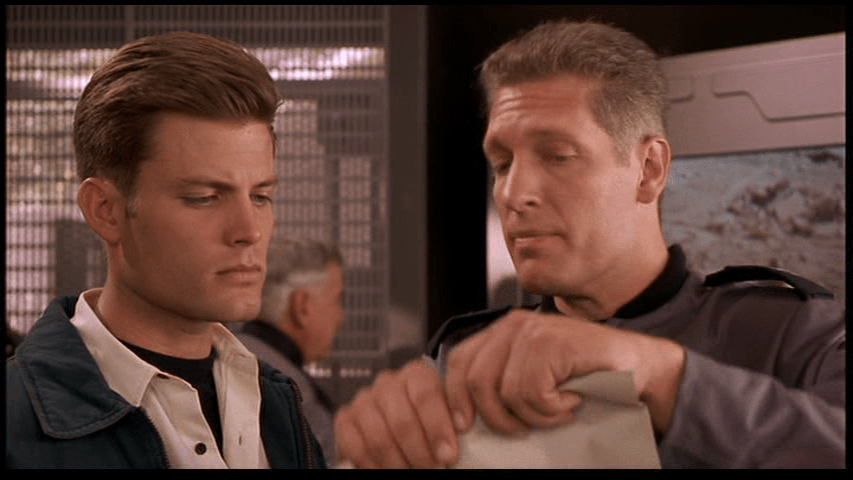

Upon revealing to Dorothy, who suspects her mother of robbing Wolf, that what she took was a metal chain known to belong to Wynant:

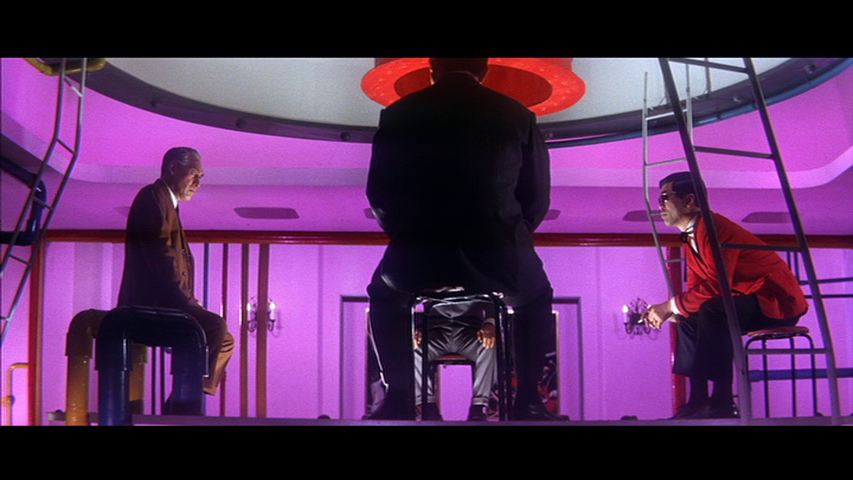

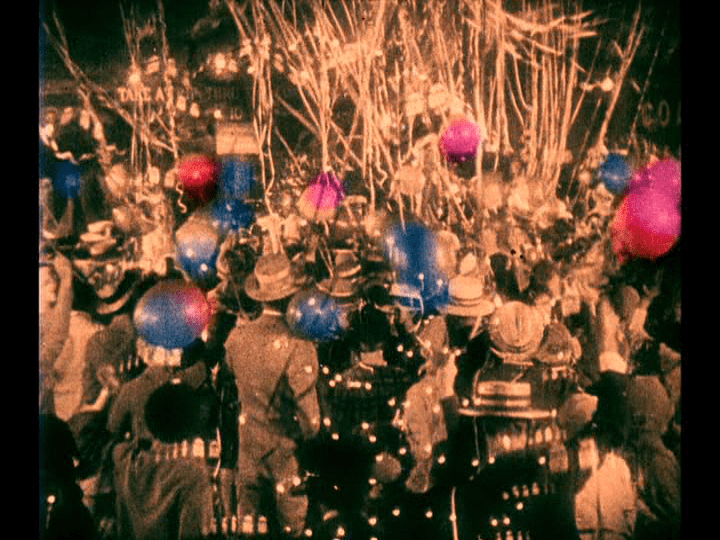

They and Dorothy’s brother Gilbert (William Henry) all descend on a Christmas party that Nick and Nora are hosting in their apartment for an eclectic collection of colorful figures from Nick’s former life. During the festivities a shady figure named Nunheim (Harold Huber) calls in with information related to the case:

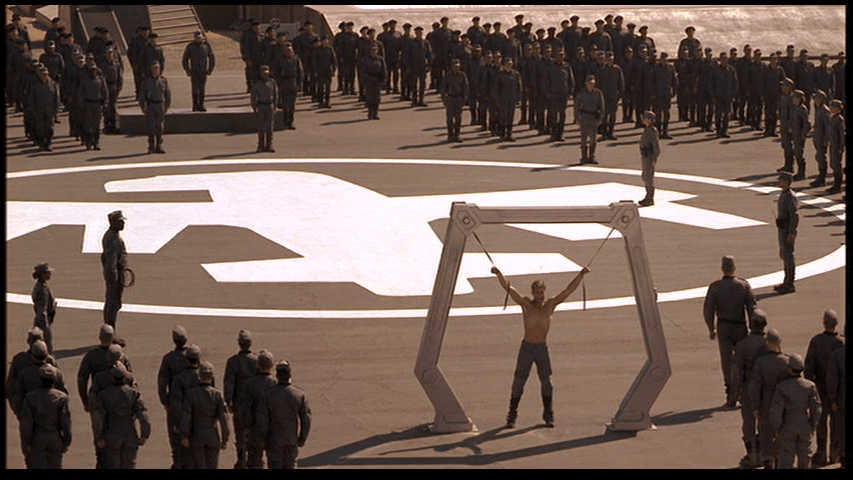

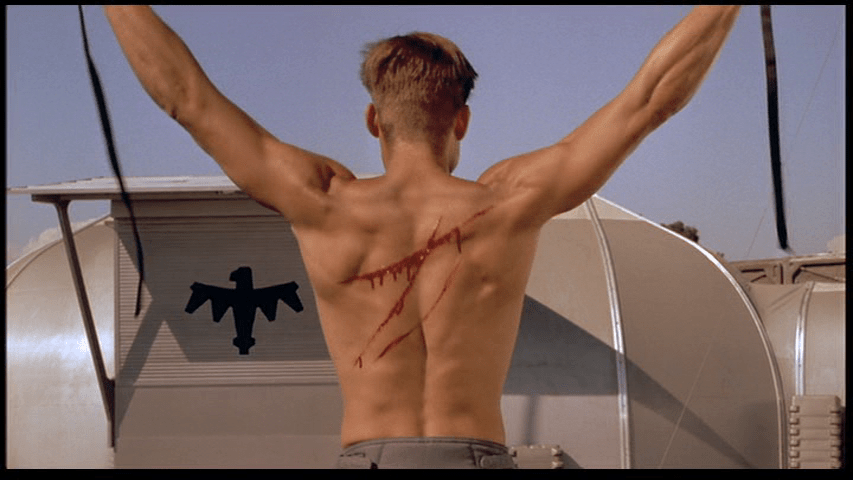

As described by Fran Mason in his book Hollywood’s Detectives, the result of all of this is to “disorder Nick’s world, most obviously when Mimi slaps Dorothy in front of Nick and Nora because she believes that Dorothy has revealed information that thwarts her plan to blackmail Wynant on his expected reappearance”:

And although it isn’t until after they leave that the party “degenerates into an anarchy of tuneless singing, drunken disagreements and maudlin sentimentality,” Mason argues that “it is implied that they cause the disorder by bringing their world of crime, venal desire and pathologies to the hotel room to disturb the small world of Nick and Nora.” Thus when Nora sighs, “oh Nicky, I love you because you know such lovely people” at the end of the evening:

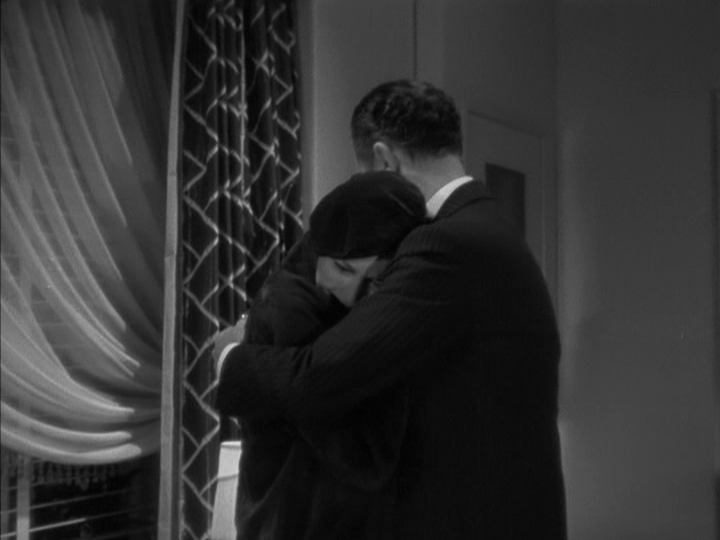

The line “applies as much to the Jorgensens and people like them as it does to the working class and underworld figures from among Nick’s acquaintances who are still present.” This sequence also again showcases the strong bond between the central couple when Nora walks in on Dorothy embracing Nick, which Kozlowski notes director W.S. Van Dyke “stages as if it would become one of those dramatic incident in which a wife sees her husband with another woman in her arms”:

He follows it with two quick pans, though, one to Nick making a face at his wife:

And then one of her crinkling her nose at him in return:

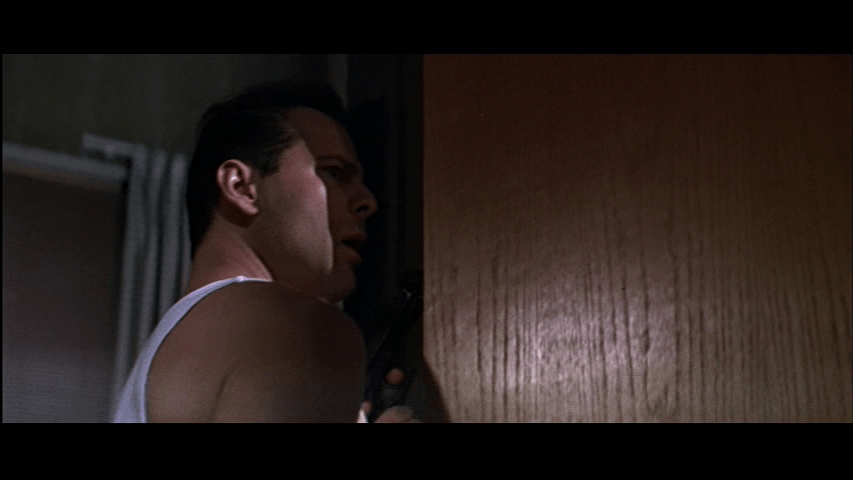

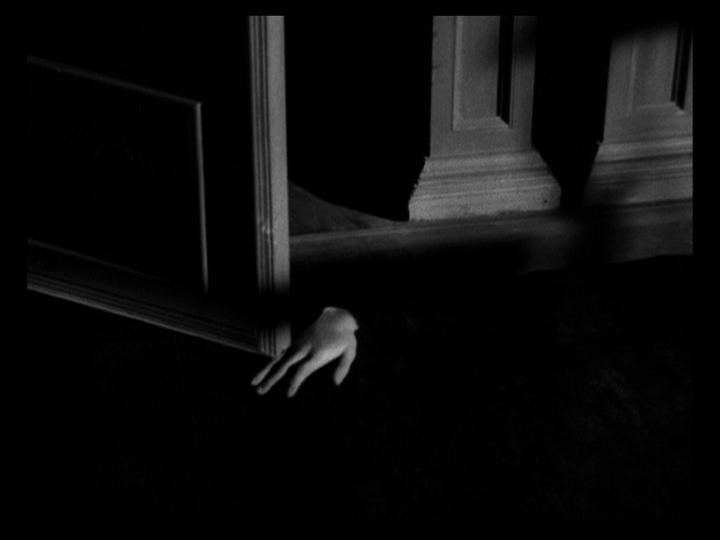

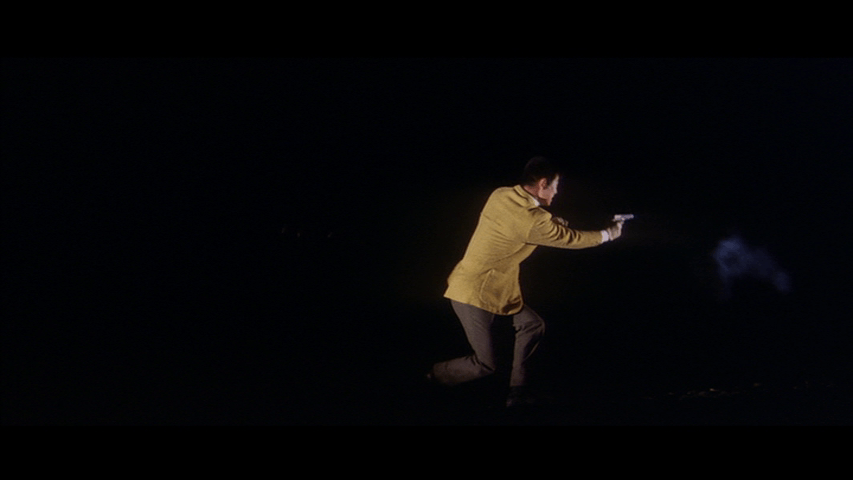

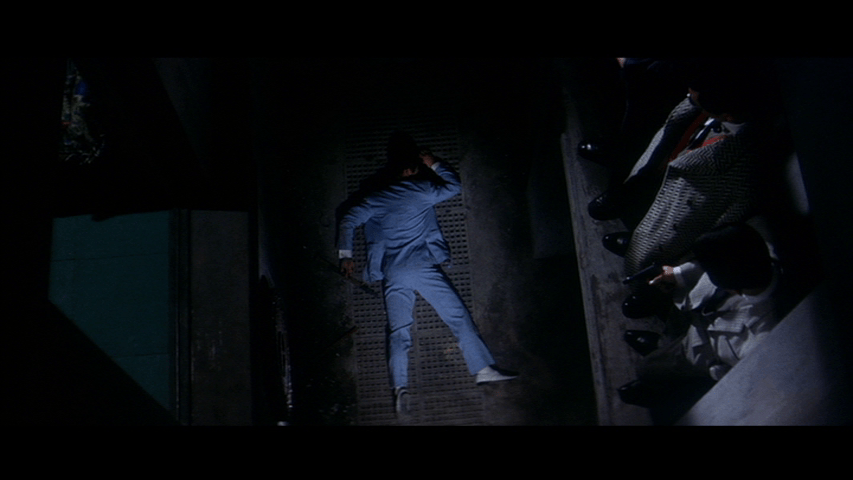

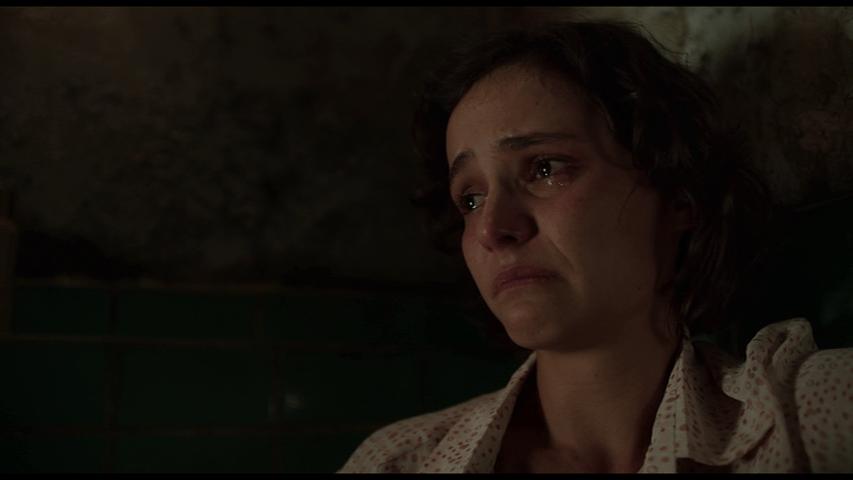

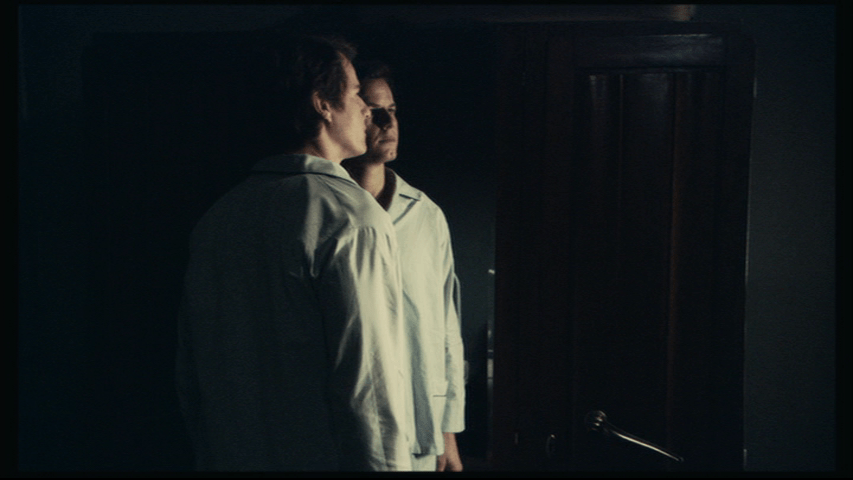

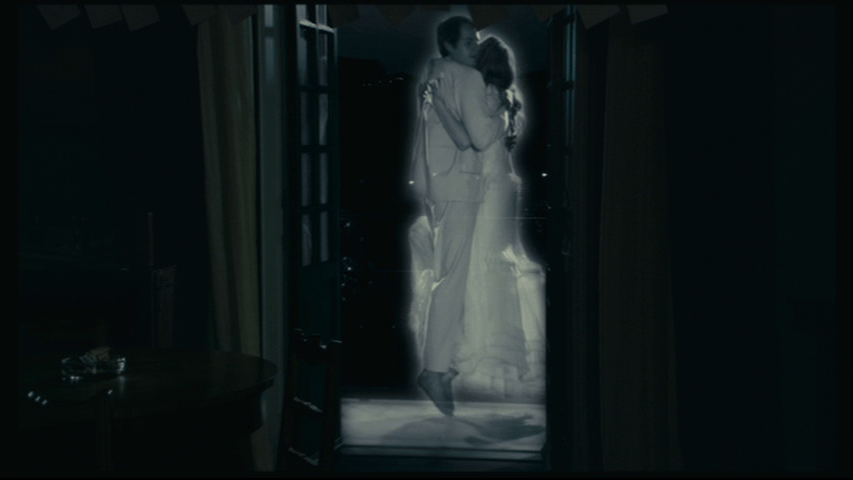

“By panning between the embrace and Nora’s reaction rather than cutting between them,” Kozlowski observes, “again we have Nick and Nora as one unit rather than being edited apart from each other, and we establish again that this married couple trusts each other completely.” That night Nick saves Nora’s life by knocking her out before the man who has broken into their apartment (Edward Brophy) can shoot her:

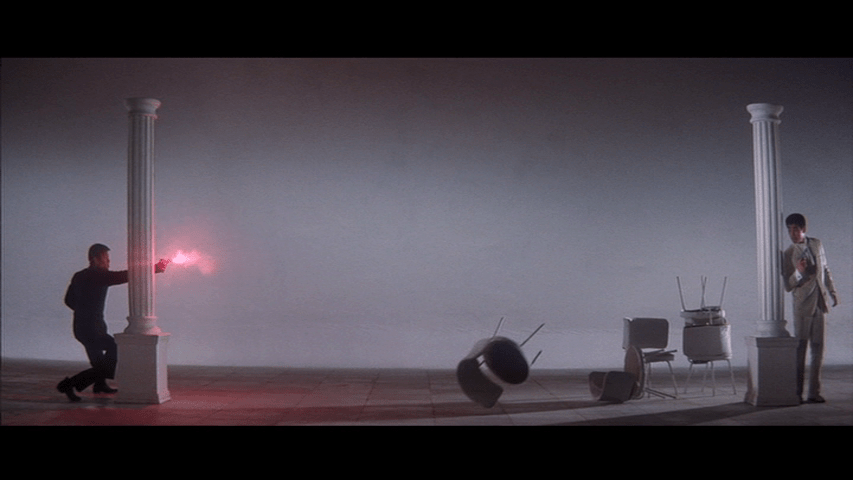

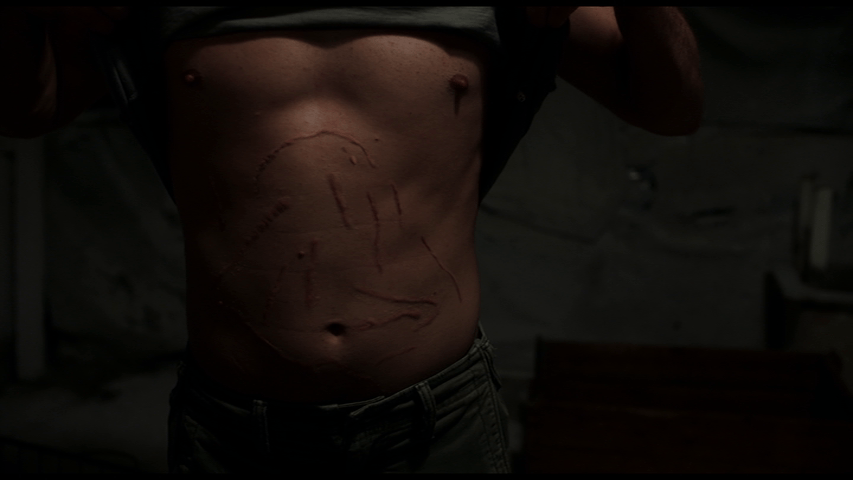

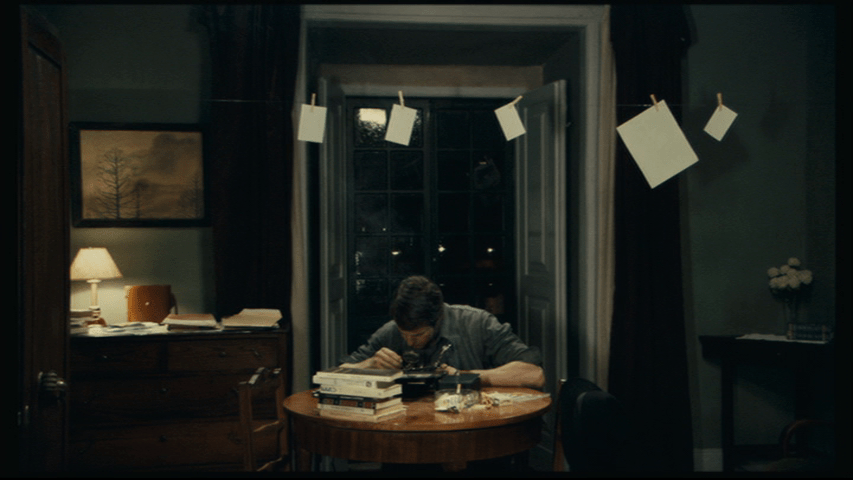

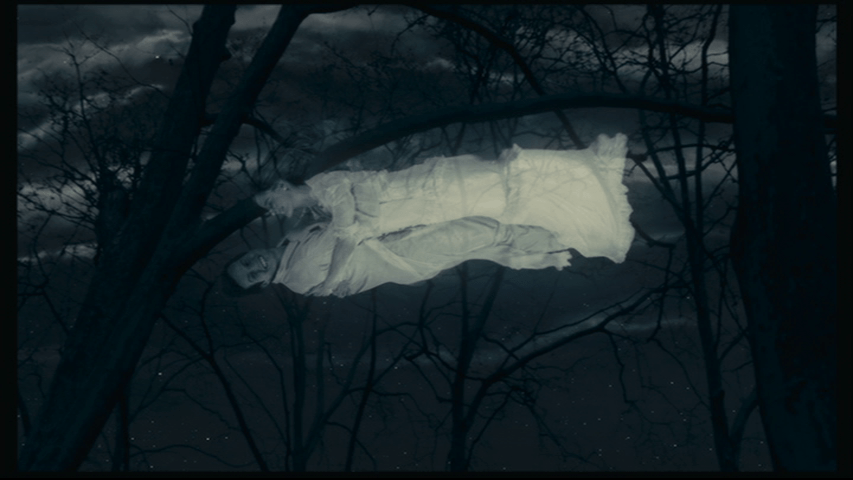

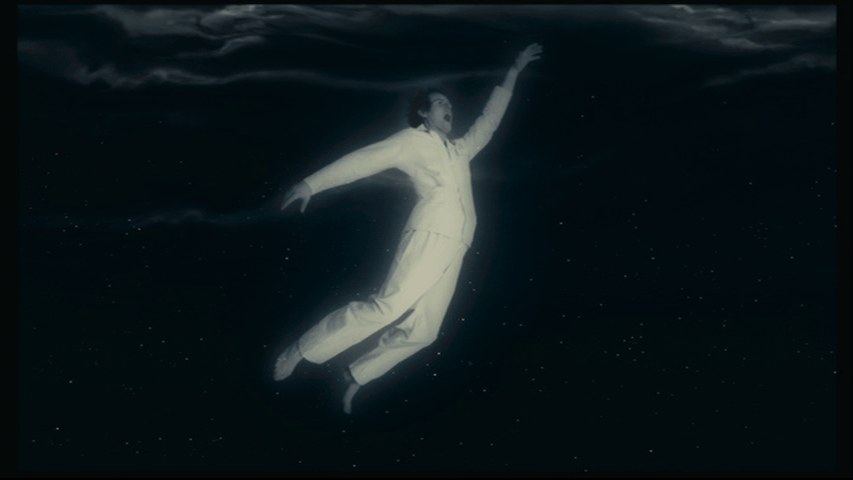

Now well and truly implicated in the case, Nick proves his mettle by solving it in relatively short order with an assist from Asta, who locates a body in Wynant’s factory when Nick decides to visit it on a hunch:

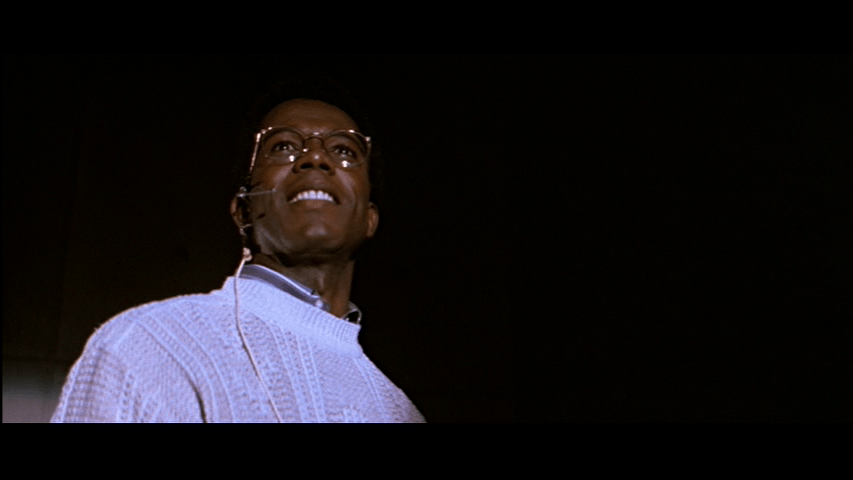

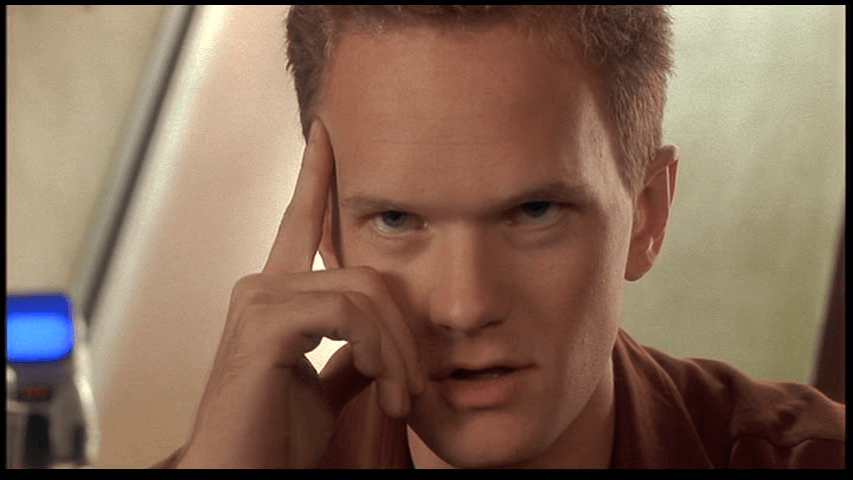

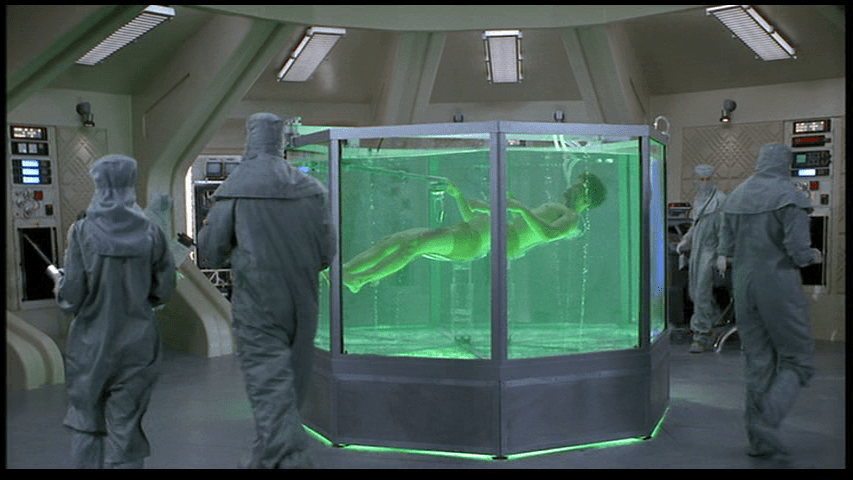

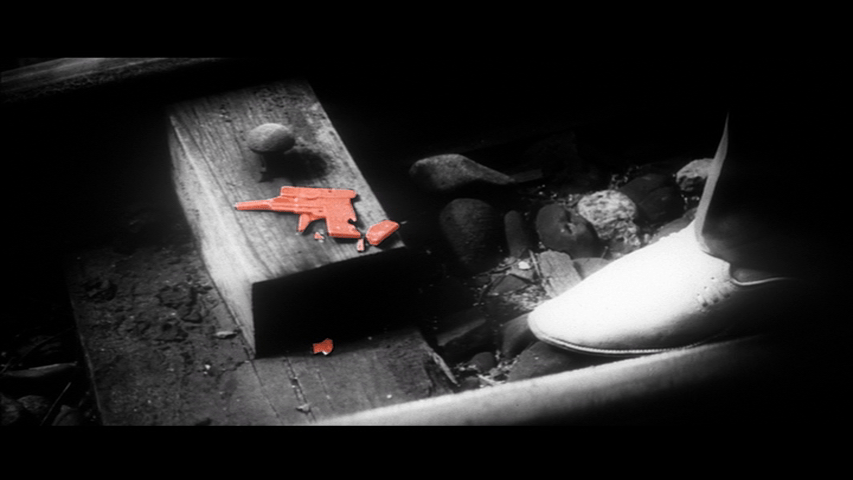

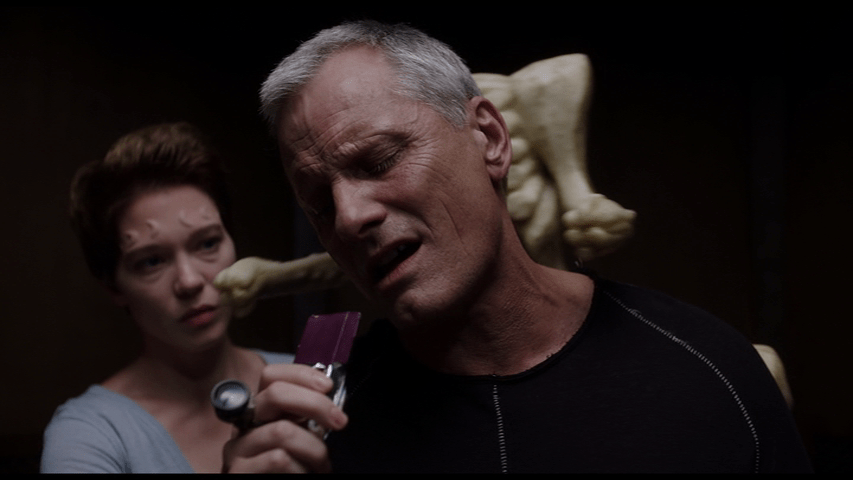

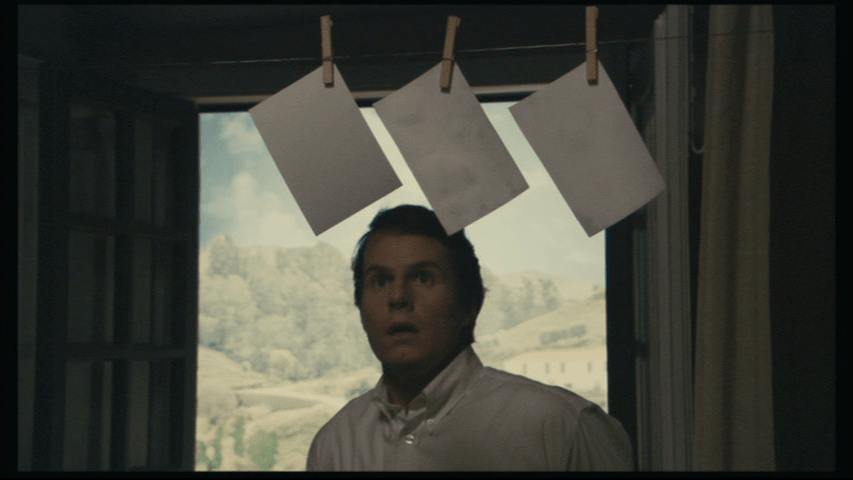

The police fall for the false clues buried with it and conclude that they’ve found someone else who was killed by Wynant, who at this point is their number one suspect, but Nick recognizes a piece of shrapnel visible in fluoroscopy:

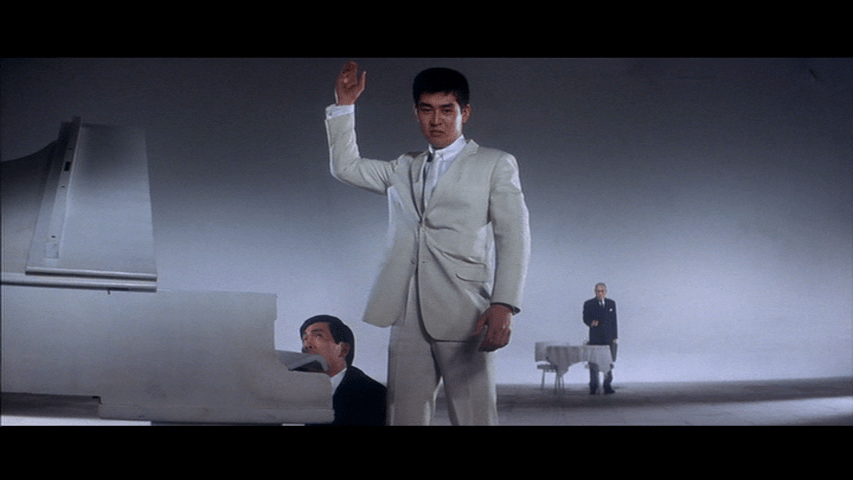

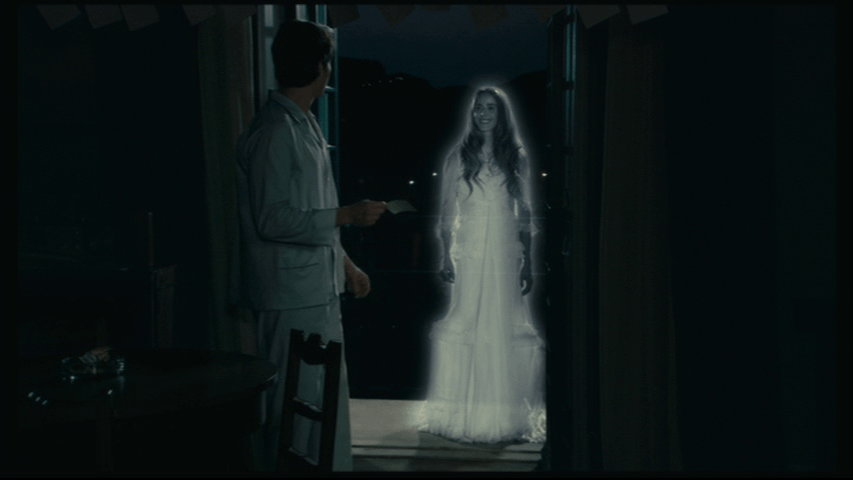

And in classic murder mystery style organizes an elaborate dinner party to reveal who *did* do it, but not before he asks if Nora has a “nice evening gown” to wear to it, which per Nochimson confirms that he shares her “forthright understanding of glamour as armor and costume that the two of them manipulate.”

She does, and it is indeed “a lulu”:

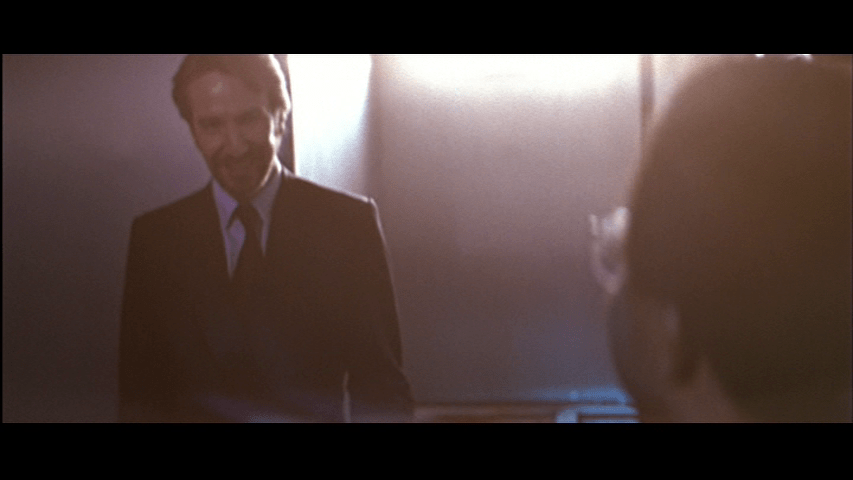

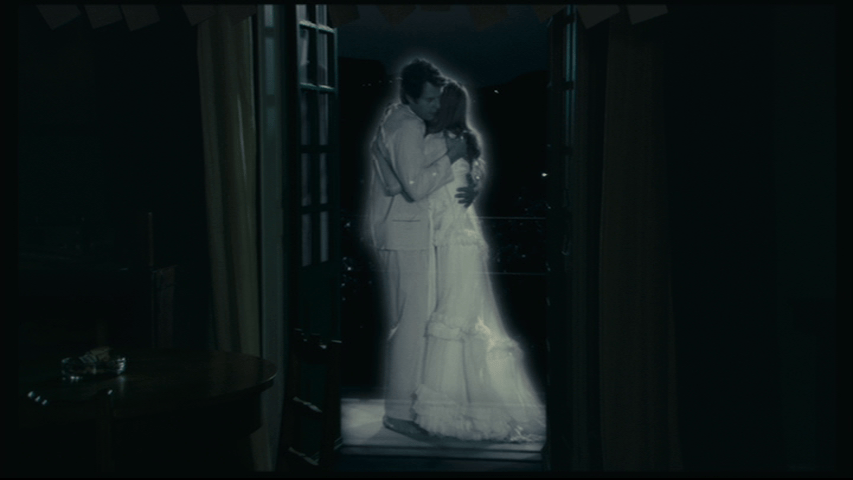

After sadistically torturing nearly every guest by suggesting that they are the guilty party, Nick provokes the real killer into incriminating themself before the main course is even served:

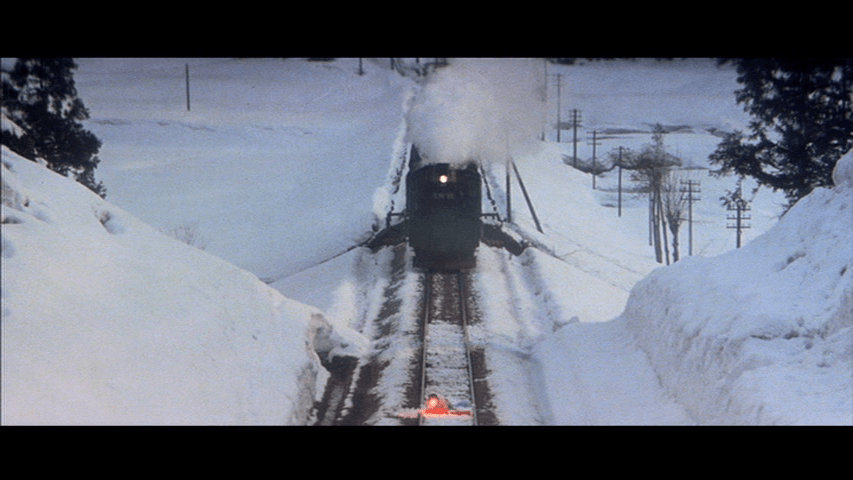

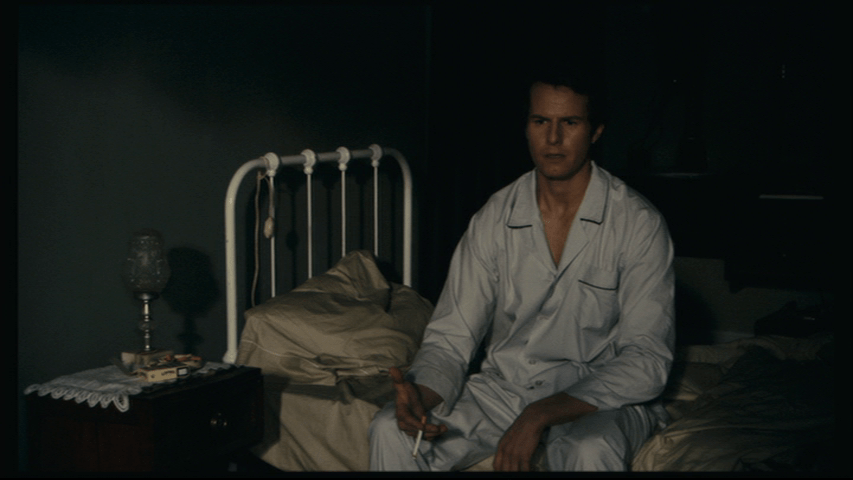

And the movie’s penultimate scene finds Nick and Nora in the sleeping car of a cross-country train toasting their success with Dorothy and her new husband Tommy (Henry Wadsworth) in an off-center composition by cinematographer James Wong Howe that makes it clear the Charles’s have overstayed their welcome by including the door:

Hopefully the honeymooners have been paying attention, because their elders have been giving them and us a master class on the art of a happy marriage. As summarized by Elizabeth Kraft in her book Restoration Stage Comedies and Hollywood Remarriage Films, the central theme is that “it is a supremely adult activity and requires both maturity and common sense, along with the opposite ability, that is, the childlike ability to play and invent and enjoy.” Which come to think of it reminds me of my description of Drink & a Movie #1 The Tamarind Seed as “a thoroughly grown-up film to enjoy with your adult beverage”! I’m not sure whether or not there’s an overarching theme there, but it strikes me as a fine place to leave off regardless. As mentioned above I’m planning to turn these posts into a book, which I think will involve a lot of cutting. A graphic designer friend has offered to help me, and I’m optimistic that the end result will make for an attractive and useful Christmas present for family and friends, so with any luck I’ll be done before next New Year’s Eve. I’ll order a few extra and sell them at cost from this site, so stay tuned if you’re interested! In the meantime, my liver has earned a good, long rest for services rendered, and I’m planning to abstain from alcohol for the duration of 2026–after all, even Nick Charles himself eventually confined himself to cider for the entire runtime of The Thin Man Goes Home! This means no cocktail commentary for awhile, but I do intend to keep up my pace of one illustrated long-form post about movies per month on average. It isn’t midnight yet, though, so I have time for one last Martini before then. Here’s to you for reading!

Cheers!

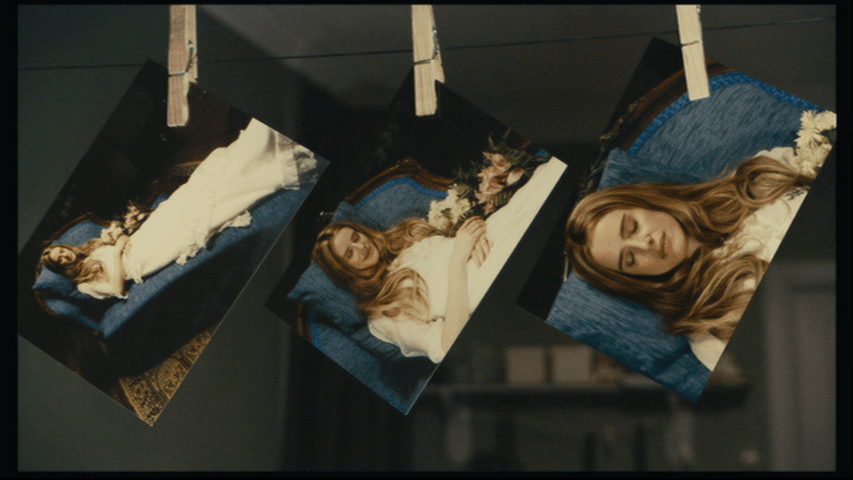

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.