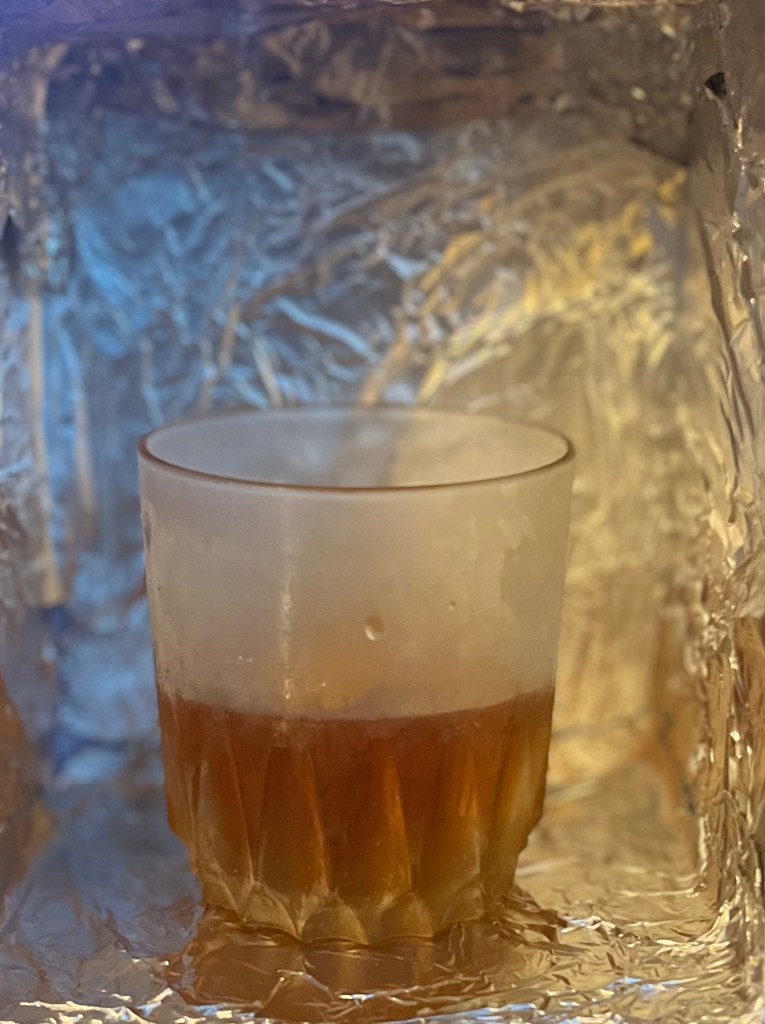

Fear not: this is not yet another polemic weirdly way too invested in convincing you that Die Hard is a Christmas movie! It *is* part of our household’s regular holiday rotation, though, so I’ve been saving a December slot for it and the Chain Smoker from Sother Teague’s I’m Just Here for the Drinks. The pairing is, of course, inspired by Bruce Willis’s John McClane, who quaintly lights a cigarette immediately after disembarking at Los Angeles International Airport approximately two minutes into the film:

Then proceeds to consume at least a full pack before the end credits roll. Here’s how you make it:

2 ozs. Mezcal (Del Maguey Vida de Muertos)

3/4 oz. Dry vermouth (Dolin)

1/4 oz. Zucca Rabarbaro

2 dashes Cocktail Punk smoked orange bitters

Stir all ingredients with ice and chain into a chilled rocks glass. Garnish with a flamed orange twist.

Teague describes the Chain Smoker as “basically a smoky mezcal Manhattan augmented with Zucca, an Italian aperitif, which has a natural smoky flavor from the dried Chinese rhubarb that serves as its base ingredient.” He notes that “the bitters add a subtle citrus note as well as another layer of smoke,” which is what dominates the nose. Flamed twists have always struck me as being more about theater than flavor or aroma, but both Teague and Frederic Yarm swear the burnt oils are a factor here as well. Regardless, agave and grape on the sip give way to a dry finish with roaring fireplace vibes, suggesting that Hart Bochner’s Harry Ellis could serve it with the “nice aged brie” he mentions while clumsily hitting on McClane’s wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia):

The image above and those which follow all come from my Sony Pictures Home Entertainment Die Hard Collection DVD set:

It’s also available on Hulu and Prime Video with a subscription.

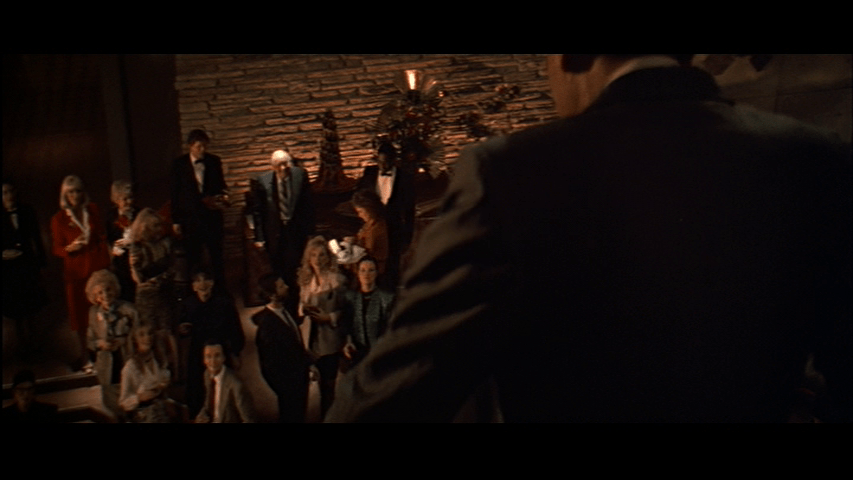

The late, great David Bordwell suggested in 2019 that Die Hard “changed ideas of just how well-wrought an action picture could be.” One way it did this was through the “ingenious ways” it finds to “let the audience’s eye go with you” in its widescreen format, which begins with the scene that immediately follows the image that begins this blog post: Holly’s boss Joseph Yoshinobu Takagi (James Shigeta), president of Nakatomi Trading, addresses the company holiday party, but with his back to the camera because we’re meant to follow Holly as she wends her way through the crowd from the elevator (in its first of many appearances) at the right side of the frame at the start of the shot:

To the hallway at the left, which is where Ellis ambushes her with his offer of old cheese and flames:

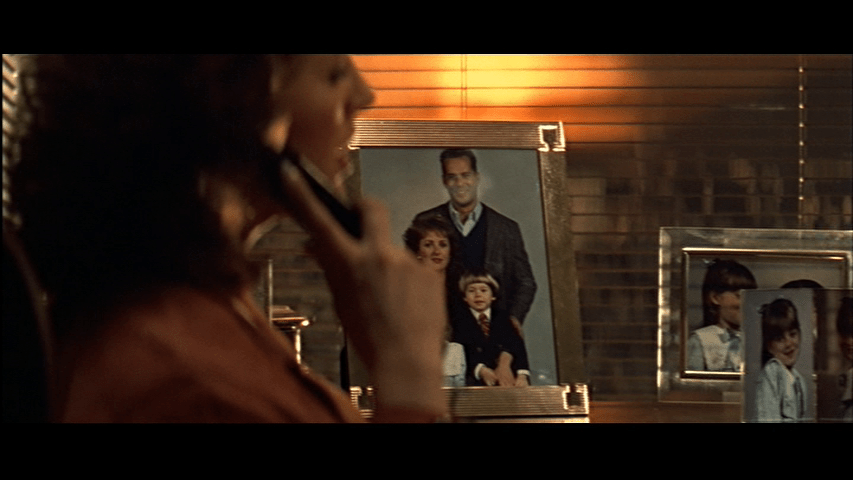

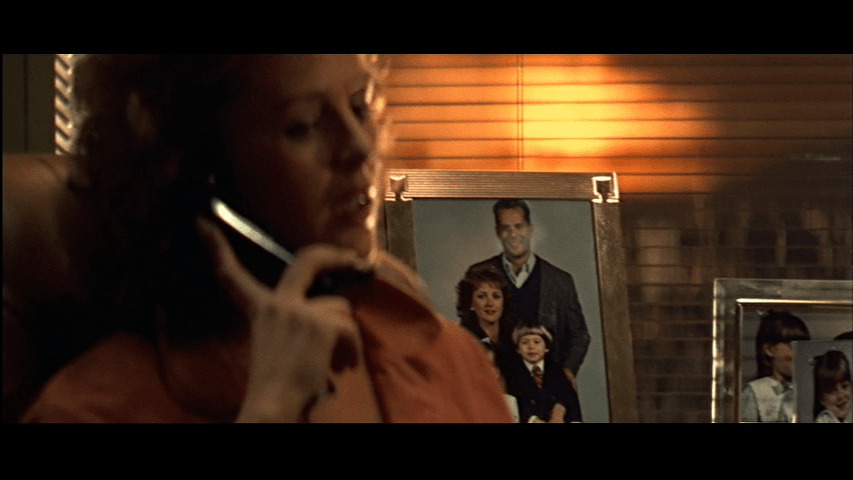

Bordwell also lauds Die Hard as “one of the great rack-focus movies,” and that technique makes an early appearance as well during a telephone call when Holly’s daughter Lucy (Taylor Fry) asks, “is Daddy coming home with you?”

“We’ll see what Santa and Mommy can do,” Holly replies. The maneuver is reversed after she hangs up:

And followed by a cut to a close-up of a family portrait upon which Holly takes out her frustration with her husband, who hasn’t communicated his travel plans to her, by slamming it down:

The photo will reappear nearly exactly one hour later, making it perhaps the most prominent example of what Bordwell calls “felicities” which mark Die Hard as a “hyperclassical film” that “spills out all these links and echoes in a fever of virtuosity.” But I’m getting ahead of myself! First McClane rides in a limo for the first time and is introduced to the holiday classic “Christmas in Hollis” by his driver Argyle (De’voreaux White), who being new to the job also doesn’t realize that it’s customary for passengers to sit in the back:

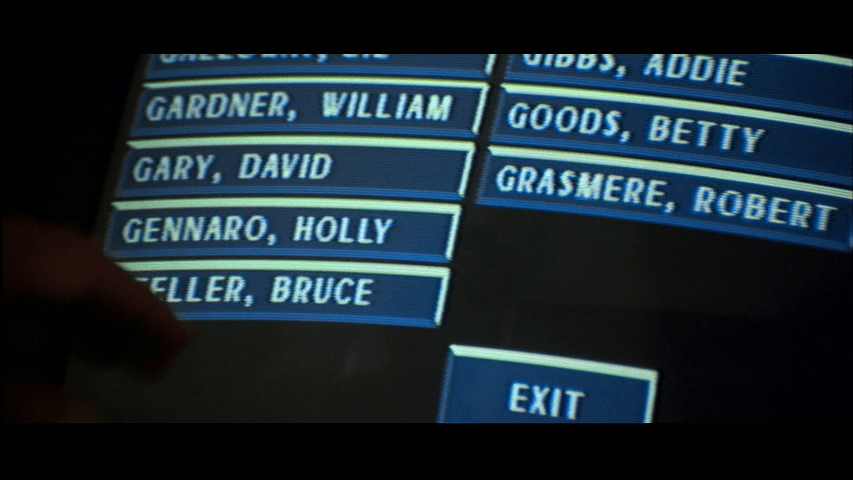

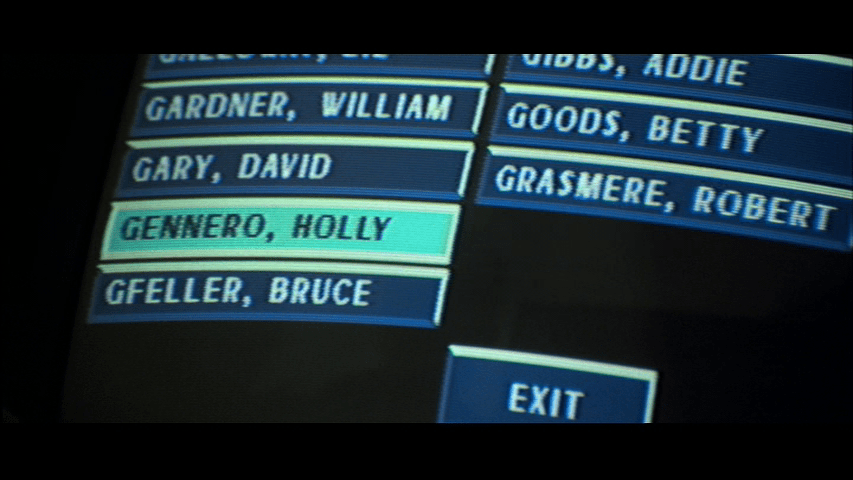

Upon arrival at Nakatomi Plaza he discovers that Holly has started going by her maiden name again when he looks her up on a computer system that may be so advanced that “if you have to take a leak, it will help you find your zipper,” but isn’t much of a consistent speller:

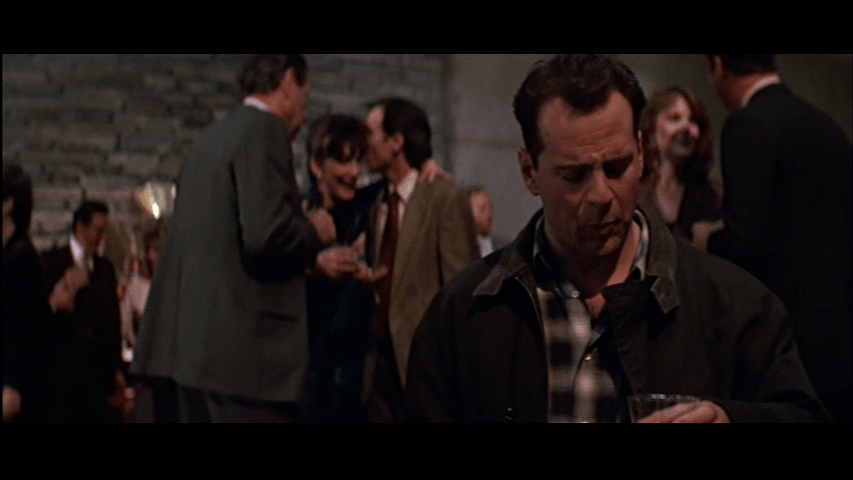

McClane joins a storied cinematic lineage with this reaction to a sip of “watered-down champagne”:

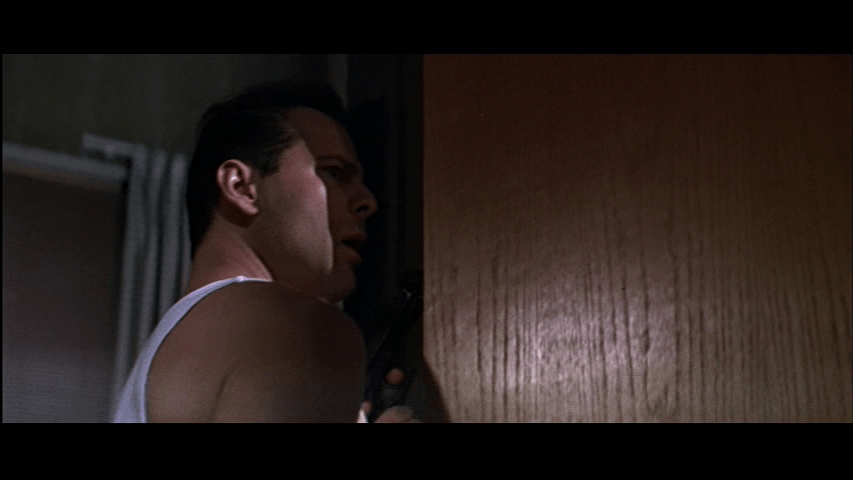

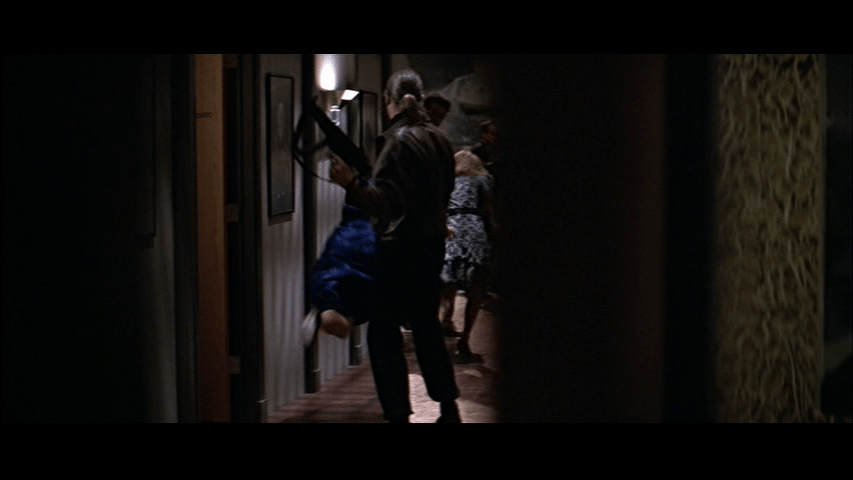

And is in Holly’s office “making fists with his toes” with his shoes off to dispel his jetlag per the advice of the “Babbit [sic] clone” (per the screenplay) he’s sitting next to in the film’s opening scenes when suddenly gunshots ring out. Grabbing his sidearm and rushing to the door, McClane ascertains that a hostage situation is underway:

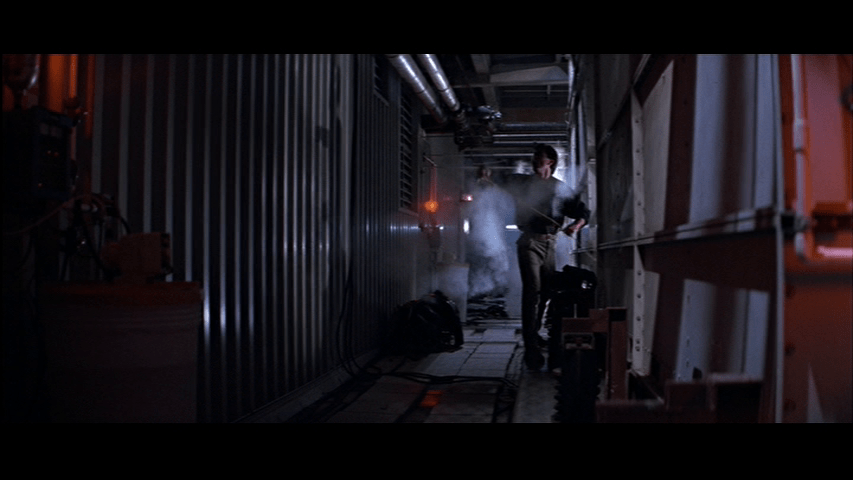

Then takes advantage of the distraction afforded by a topless partygoer to escape into what according to James Mottram and David S. Cohen’s Die Hard: The Ultimate Visual History production designer Jackson De Govia saw as the “steel jungle” of the not-yet-complete Nakatomi building’s stairwells, thus setting in motion what he calls “a survival drama in the context of architecture that’s under construction.” As criminal mastermind Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman) carefully lays his plans, which include wiring the roof with plastic explosives so that he and the members of his team (all of whom, as Nick Guzan details in a terrific blog post ranking their wardrobes, “have distinctive roles, attitudes, and aesthetics”) can eventually fake their own deaths:

And convincing the FBI that he’s a terrorist by way of manipulating them into cutting the power to the building and automatically releasing the last, otherwise unbreakable, lock guarding the company’s vault:

McClane adapts to his new environment. He uses an elevator as a duck blind to scout his foes without being seen:

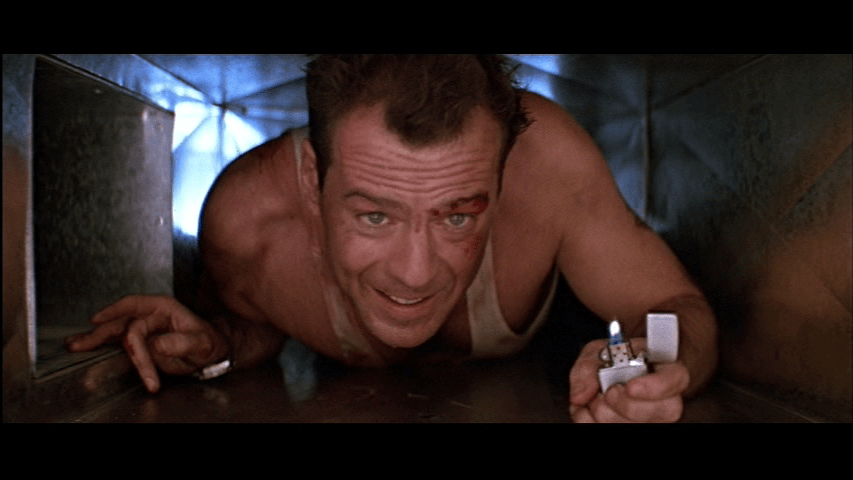

Hides in the cave-like vents that inspired this month’s drink photo:

Sets traps:

And successfully navigates a shootout through a conference table that De Govia chose for the way it “moves like a river”:

That altercation ends with McClane taking a bag of explosives off the body of one of his fallen adversaries while he identifies himself to Gruber over a walkie-talkie as “just the fly in the ointment, Hans, the monkey in the wrench.”

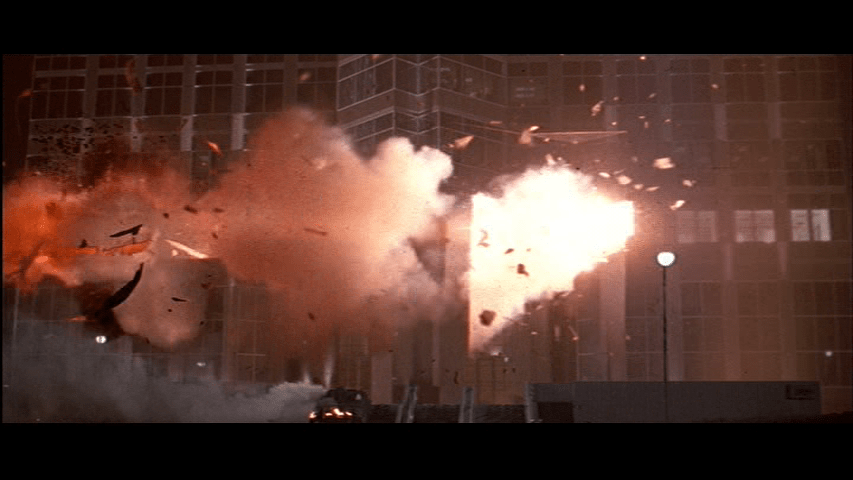

From this point forward they oppose each other more directly. First McClane retaliates against Gruber for firing a second anti-tank at an already disabled police vehicle just to make a point by strapping a bomb to a chair and dropping it down an elevator shaft, taking out two of Gruber’s men:

Then Gruber shoots Ellis, who not understanding what he’s up against, foolishly tries to convince McClane to turn himself in:

McClane meets Gruber face to face in a scene replete with unsettling canted angles when the latter goes to check on the explosives on the roof, but initially fails to recognize him when Gruber cleverly clocks a floor directory and pretends to be a hostage named Bill Clay:

Gruber also notices that McClane is shoeless and is able to hobble him by summoning his henchman Karl (Alexander Godunov) and ordering him to “shoot the glass”:

While McClane tends to some of the most painful-looking wounds in cinema history:

Gruber takes advantage of his absence to achieve his goal of gaining access to the $640 million worth of bearer bonds in Nakatomi Trading’s vault in a scene that Robynn J. Stilwell argues in a 1997 Music & Letters article “clearly constructs [him] as a sympathetic, heroic figure as aural and visual cinematic cues and narrative drive come together,” including the “rhythmic speech” of hacker Theo (Clarence Gilyard Jr.) building with the music toward a full-throated statement of Gruber’s Beethoven-based theme, a shot from a “low, powerful angle” of him rising “slowly, awestruck, to his feet, a little breeze ruffling his hair in the halo of the brilliant emergency light”:

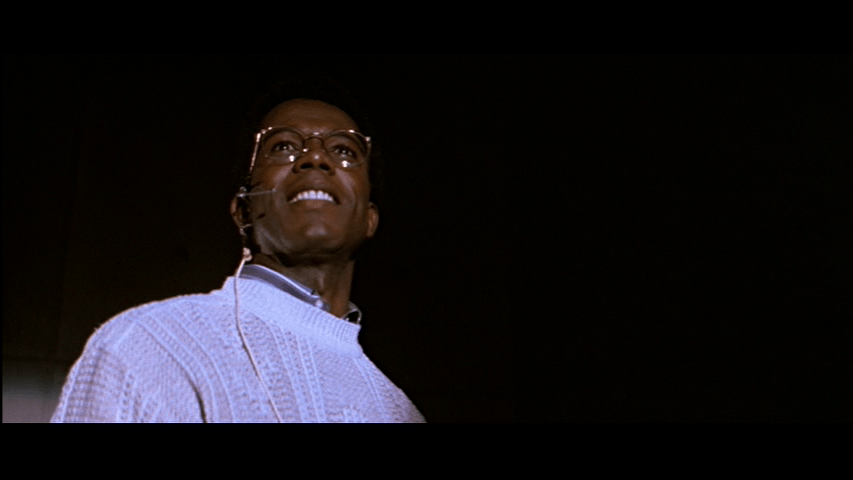

Theo whispering “Merry Christmas” in another striking low-angle composition which dramatically sets him and his white sweater off against the pitch black of the rest of the frame:

And a euphoric tour of the vault’s contents that follows a shot of FBI agents Johnson (Robert Davi) and Johnson (Grand L. Bush) foolishly gloating that “those bastards are probably pissing their pants right now”:

Which makes sense when you remember that, as screenwriter Steven E. De Souza told Dan Frazier in an interview, “if you’re doing genre, the protagonist is the villain.” But while we may be “given every possible opportunity to read Hans as the hero of a caper film,” as Stilwell puts it, “classic Hollywood closure […] demands two things: that Hans die, and that Holly and John McClane are reconciled.” And so Die Hard doesn’t end here. Instead, McClane puts all the pieces together and heads back upstairs, where he battles Karl to the death, saves the hostages from being blown to smithereens, and leaps off the roof of Nakatomi Plaza:

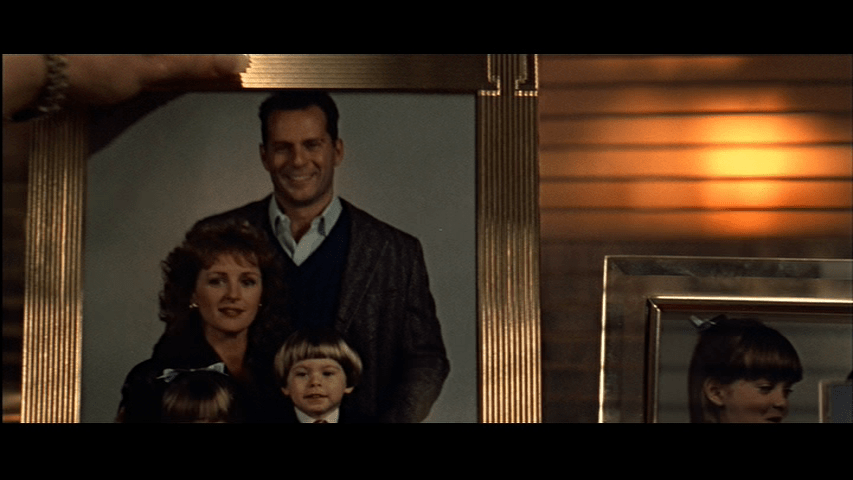

Meanwhile, Gruber solves a puzzle himself when he discovers the picture we talked about earlier and finally figures out how a New York City cop came to be in position to interfere with his California heist:

“Mrs. McClane, how nice to make your acquaintance,” he says, setting the stage for a final showdown.

In his introduction to Mottram and Cohen’s book, director John McTiernan reveals that the inspiration for Die Hard came from a surprising source:

In this case, it was easy. It was right in Shakespeare. He wrote a bunch of plays he called comedies. They weren’t funny ha-ha the way we mean it. They were fun. Basically, fun adventures. And I was pretty sure that one of them fit.

It was about a festival night on which something crazy happens–and for everybody involved, the world is turned upside down. The princes become asses, and the asses become princes, and in the morning the world is put back right and the lovers are reunited.

Now the plot of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is way more complicated than that, but don’t look at that. Look at the totality. It was right there: Tell the story not of the cop and the terrorists but of the people who are part of the event. Let the audience sit back and watch the craziness as a whole. Let them enjoy it.

To Matt Zoller Seitz, writing on the occasion of the film’s 25th anniversary, this sense of fun is what makes the Die Hard great. Citing this shot of a S.W.A.T. team member pricking himself on a thorn as a particularly memorable example:

Zoller Seitz notes that “there’s a strain of satire coursing through the picture” and that “more often than not, what’s being made fun of is machismo itself.” He observes that “McClane is mostly spared this sort of scrutiny, but not always,” which to me is crucial to understanding its ending. First, there’s the specific manner of Gruber’s demise: he plumets to his death only after McClane unclasps a Rolex watch that Holly was given by her employer, which Roderick Heath describes as “a symbolic wedding ring to the new age of rootless money-worship” in a turn of phrase that reminds me of last month’s Drink & a Movie selection.

Afterward McClane spots the beat cop Sergeant Al Powell (Reginald VelJohnson) who supported him throughout his ordeal across a crowded courtyard:

He introduces Holly as “my wife Holly . . . Holly Gennaro,” but she corrects him with a line that understandably rubs a lot of people the wrong way: “Holly McClane“:

In this moment they both clearly think they’ve changed, sure, but why should *we* believe it? After all, as Stilwell points out, “despite the ‘happy ending’ in this film, Holly is still not back ‘in her place’ in the sequels,” evidence perhaps that McClane has more John Wayne in him than Roy Rogers after all. Maybe, to paraphrase Puck’s final speech in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, we should instead think but this, so all is mended, that we have but slumber’d here while these last few visions did appear. Certainly that would make Karl’s subsequent improbable reappearance easier to stomach!

So light ’em if you got ’em, or pour yourself another Chain Smoker if you don’t, and let it snow, let it snow, let it snow!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.