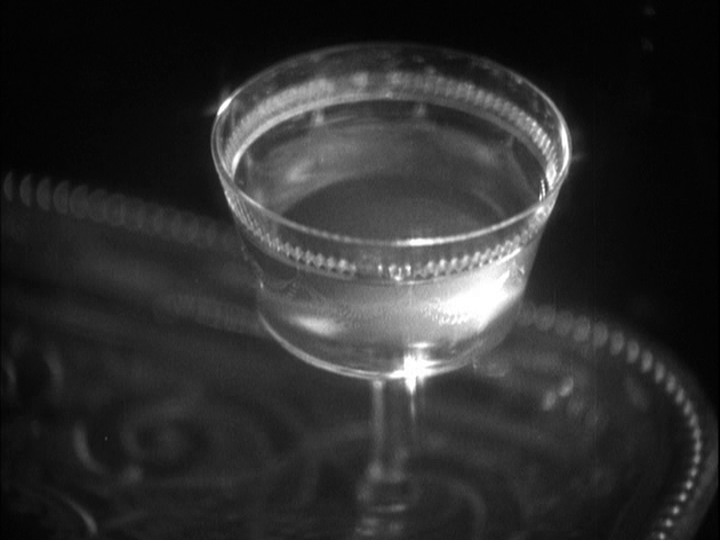

If you’ve been following this series from the start, it is no doubt obvious to you by now that when it comes to both drinks and movies, there’s nothing I prize more than thoughtful twists on familiar templates. I’ve been keeping one of my very favorites in reserve, but with fall in full swing it’s finally time to raise a glass to the Normandy Cocktail invented by novelist and famous tippler Kingsley Amis as a cheaper apple-based alternative to the classic Champagne Cocktail. As he says in his book Everyday Drinking, “Calvados is a few bob dearer than a three-star cognac, but the classiest cider is a fraction of the cost of the commonest champagne.” Amis originally penned those words in England in the early 1980s, and while they may not still be true today, his description of his creation as “a delicious concoction, deceptively mild in the mouth” absolutely is. Here’s how we make it using ingredients from closer to home:

2 ozs. Laird’s 10th Generation Apple Brandy

3 ozs. South Hill Cider’s Baldwin

1 dash Angostura bitters

1 tsp Demerara syrup

Stir the brandy, bitters, and syrup with ice and strain into a chilled champagne coupe. Add the sparkling cider and garnish with an apple slice.

The Normandy has an apple candy nose, but champagne flavors from the cider, which South Hill’s website accurately describes as “bone dry,” dominate on the way down. This includes toasty notes that I like a lot. The finish is all tart apple (“like a MacIntosh,” said My Loving Wife), though, reminding you what you’re drinking and of the season. The Cornelius Applejack I featured in my September, 2022 Drink & a Movie post is an even more local option for upstate New Yorkers, but I like the extra oomph you get from the higher ABV of the Laird’s; it does, however, result in a quite boozy cocktail that as Amis writes “tends to go down rather faster than its strength calls for,” so be careful lest you too end up with “heads in the soup when offering it as an apéritif”!

The movie I’m pairing it with also has an English provenance and is positively drenched in bubbly. Here’s a picture of my “Alfred Hitchcock: 3-Disc Collector’s Edition” DVD box set by Lions Gate which includes The Ring:

It is also streaming on Tubi and a variety of other free platforms, albeit not as many as I would have expected considering that it entered the public domain in the United States a few years ago.

Director Alfred Hitchcock famously referred to The Ring in François Truffaut’s book-length interview with him Hitchock/Truffaut as “the next Hitchcock picture” after The Lodger; as nearly everyone who writes about it inevitably notes, it’s also the only one in his long career that he ever directed from his own original screenplay (although most sources agree that his wife Alma Reville contributed to it as well). It begins with a series of images from a carnival that Christopher D. Morris characterizes as “a vertiginous multiplication of circles, of frantic and enforced gaity” in his book The Hanging Figure: On Suspense and the Films of Alfred Hitchcock that includes an opening close-up of a drum followed by a shot of children on a swing ride:

A point-of-view shot from the perspective of a woman on a gondola ride:

A grotesque extreme close-up of a barker’s mouth:

And two sadistic little boys throwing rotten eggs at a Black man in a dunk tank under the eye of a police officer that only becomes watchful when a higher, disapproving authority figure appears:

It becomes obvious in the very next scene that the fellow standing behind the two hooligans in the first image above, who we will eventually learn is named Bob Corby (Ian Hunter), is one of our main characters. He spots a woman through the crowd whom a title card identifies only as The Girl (Lillian Hall-Davis), but who a telegram will later reveal is named Mabel:

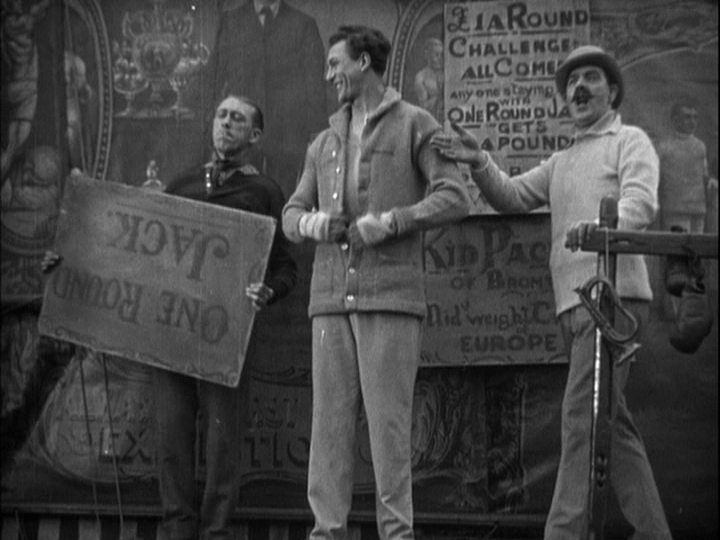

Alas for him, she’s romantically attached to her co-worker “One-Round” Jack Sander (Carl Brisson), who takes on all comers with the promise that if they can last just a single round in the ring with him, they’ll win a pound:

In a scene that Raymond Durgnat praises in his book The Strange Case of Alfred Hitchcock for the way it “picks out the variety of types who make a crowd; none, in themselves, highly original or individual; but the whole is more than the sum of its parts,” a number of men either confidently step forward to fight Jack like this burly sailor:

Or reluctantly allow themselves be cajoled into do like this henpecked husband:

Corby appears to be a variation on that theme, given that he seemingly only throws his hat in the ring after Sander goads him into it when he spots him flirting with Mabel:

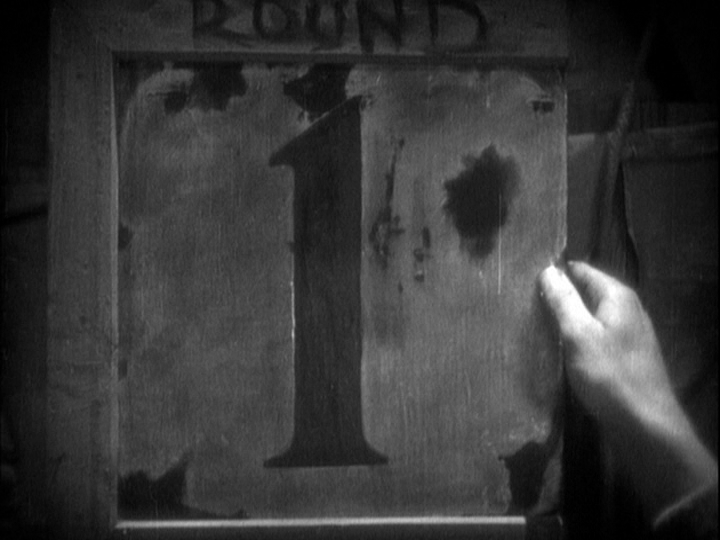

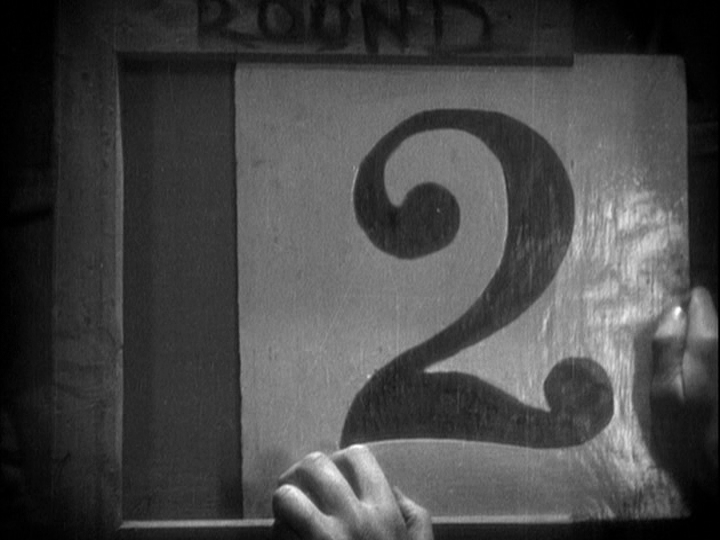

But we soon realize that he’s a different animal entirely from his fellow challengers through a device that Hitchcock (“winningly,” per Durgnat) sounds quite proud of when describing it to Truffaut: “at the end of the first round the barker took out the card indicating the round number, which was old and shabby, and they put up number two. It was brand-new! One-Round Jack was so good that they’d never got around to using it before!”

Much of the fight is shown from Mabel’s perspective, which means we don’t actually see much since she’s watching from her post at the ticket booth:

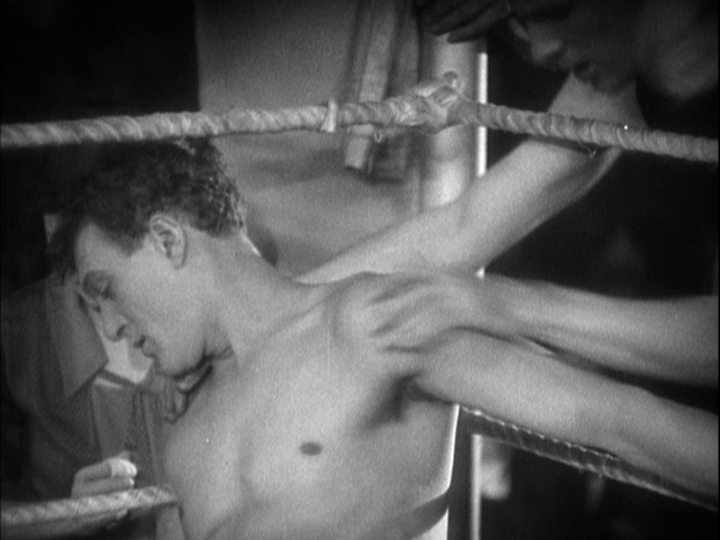

But we do cut to an interior medium long shot for its final moments:

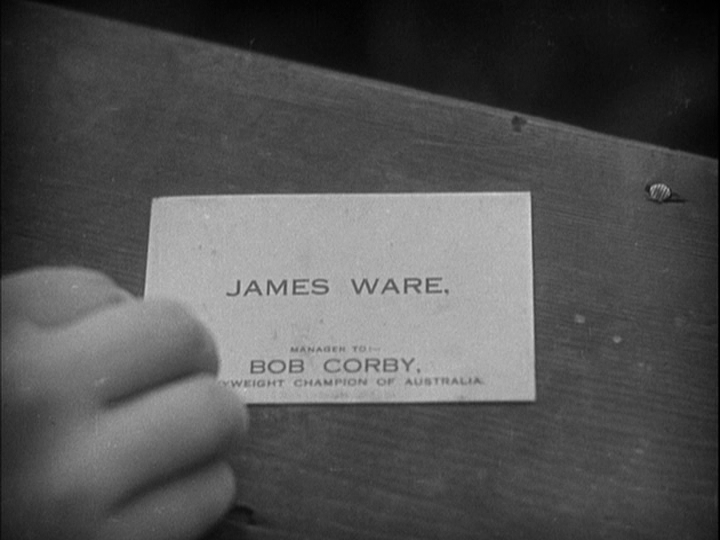

Mabel is initially pretty displeased at the result. “We were hoping to get married, and now you’ve probably lost him his job!” she tells the victorious Corby and his companion (Forrester Harvey):

But is all soft-focus smiles when they reveal who they are:

When they return that evening to offer Sander a job as Corby’s sparring partner, the latter presents Mabel with an armlet, which Hitchcock cleverly portrays as being part of a single devil’s bargain:

A fortune teller (Clare Greet) sees the whole thing and tries to warn Mabel (to paraphrase Don Henley and Glenn Frey) not to draw the king of diamonds, girl, because the king of hearts is always her best bet, but Sander blunders in and declares, “that’s me. Diamonds–I’m going to make real money now.”

He remains oblivious through the armlet falling into a pond right in front of him when Mabel explains that because Corby purchased it with money he won from fighting Sander, “it was really you who gave it to me”:

And the boorish toast Corby makes after Sander and Mabel finally wed: “I think the prize at the booth should have been this charming bride; anyway, now he’s my sparring partner I shall take my revenge”:

But it isn’t until the film’s near-exact halfway point that he finally gets wise and acknowledges that, “it seems as though I shall have to fight for my wife, after all”:

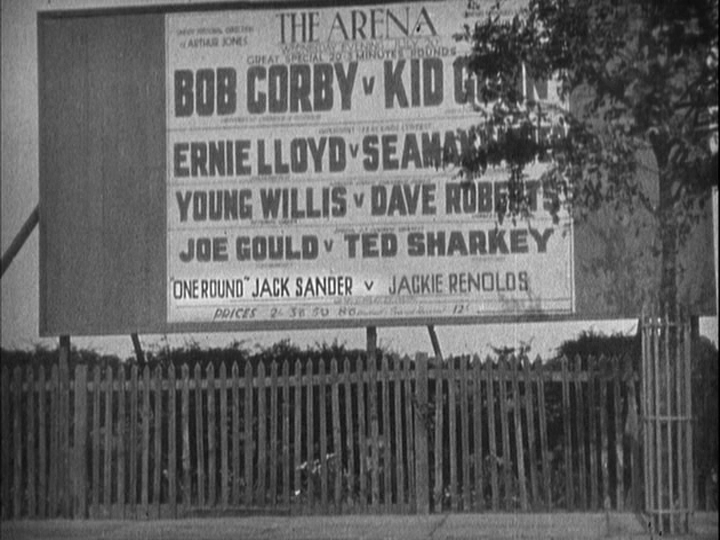

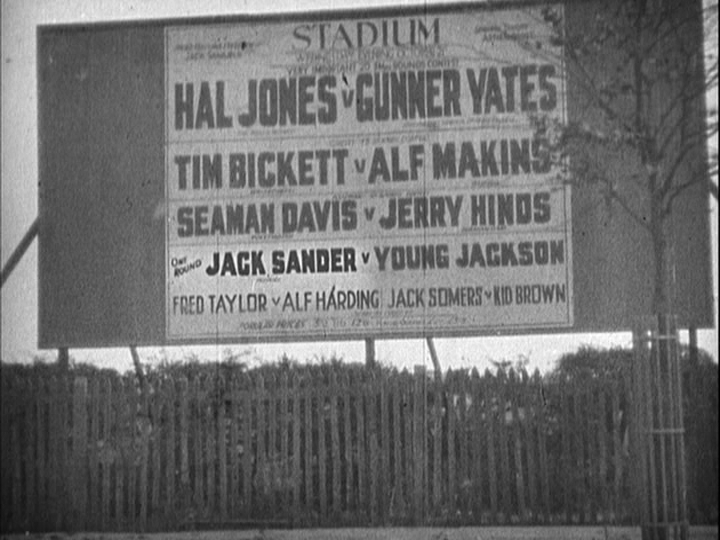

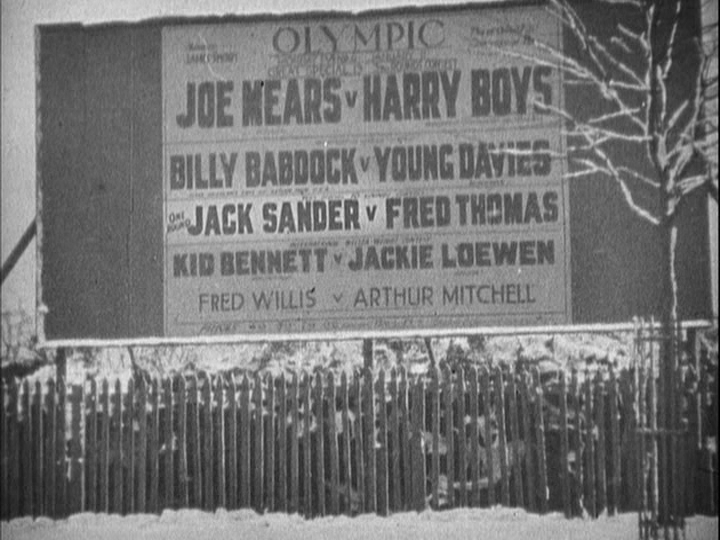

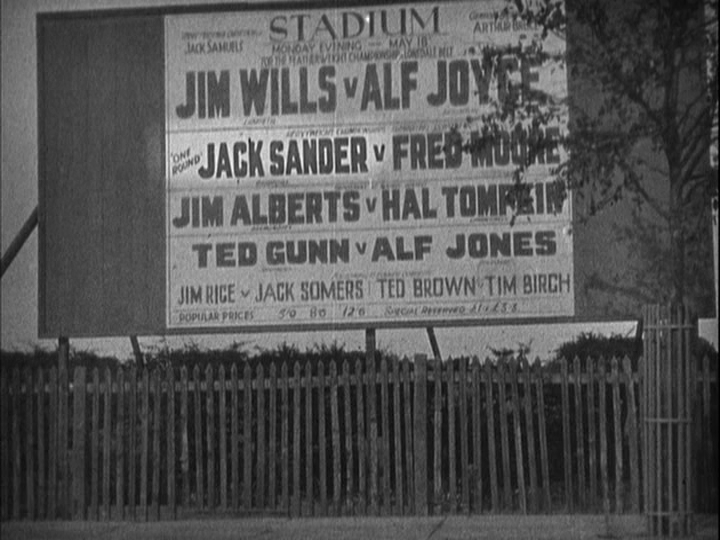

This is followed by another montage technique that Hitchcock claims credit for inventing in his interview with Truffaut: “to show the progress of a prize fighter’s career, we showed large posters on the street, with his name on the bottom. We show different seasons–summer, autumn, winter–and the name is printed in bigger and bigger letters on each of the posters. I took great care to illustrate the changing seasons: blossoming trees for the spring, snow for the winter, and so on.”

Sander is by now plagued by surrealistic nightmare visions of adultery:

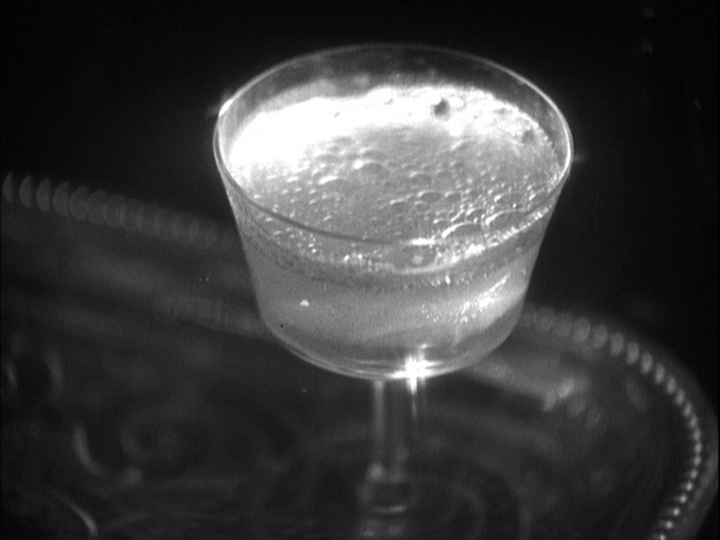

But nonetheless manages to win his next fight, securing him a title bout with Corby. Mabel isn’t there when he arrives home to celebrate, though. He pours champagne for his friends, who stare at it as intently as starving men ogling the first food they’ve seen in weeks:

But expecting her arrival any minute, he insists that they wait. “And so,” as Hitchcock tells Truffaut, “the champagne goes flat”:

Not content with merely wasting their contents, an enraged Sander finishes off the glasses themselves when Mabel finally gets home by throwing a framed photo of Corby at them:

She uses the photo as a shield after he rips her dress a few seconds later and flees:

Sander goes looking for Corby and upon finding him continues his vendetta against sparkling wine by way of rejecting a peace offering:

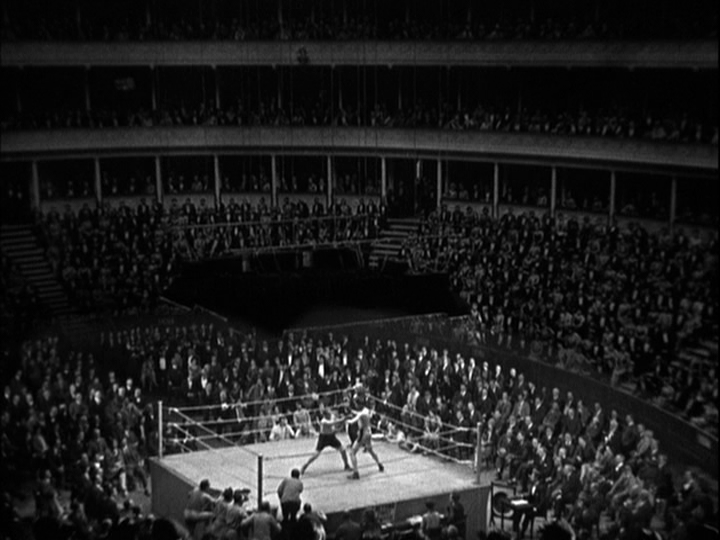

They basically decide to settle things in the ring, and that’s where most of rest of the film takes place. In his monograph on Hitchcock, Patrick McGilligan calls this sequence, which is set in Albert Hall, “a triumph of illusion, indebted to the recently invented Schüfftan process, first exploited by Fritz Lang in Metropolis, and which Hitchcock had brought home from Germany as his most valuable souvenir.” Per McGilligan, this technique allowed the director “to stage scenes in public places, without the expense (or permission) of actually filming there, by blending live action in the foreground against miniatures, photographs, or painted scenery.”

The fight is also noteworthy for Hitchcock’s documentarian eye for things like canvas preparation:

And a film crew getting ready to record it:

The judicious use of first-person shots to heighten the drama of big hits like this one:

And another bubbly being opened and dumped on Sander’s head to revive him ahead of the penultimate round:

At this point it looks like our hero is on his way to another loss, but the tide turns when Mabel discards the fur coat Corby gave her and goes to Sander before the final bell:

“I’m with you . . . in your corner,” she tells him. What’s interesting is how he becomes aware of her presence. Here’s how Michael Walker describes it in his book Hitchcock’s Motifs:

By now, Jack is too dazed to realise she is beside him, reassuring him that she’s back, but as he looks down at his pail of water, he sees her reflection. In fact, Hitchcock films this subjective image ambiguously: since Mabel’s image in the water dissolves into a reflection of Jack looking at himself, it is not certain that her reflection really is there or whether Jack has conjured it up from hearing her voice.

This is, perhaps, why the tender look Mabel and Sander exchange after he knocks Corby out doesn’t seem to presage a happily ever after.

As Walker says, “the connection between Mabel and water suggests her elusiveness: she becomes as difficult to hold on to as her reflection.” Of course, although we fade to black, this isn’t the movie’s final shot! Hitchcock instead chooses to end with Corby in his changing room. “Look what I found at the ring-side, Guv’nor,” says a member of his team, holding up the armlet he gave Mabel:

Corby contemplates it for a single beat:

Then flips it back to the person who found it and resumes adjusting his collar:

“It’s this lazy, sharp, sensible, apathetic gesture which, retrospectively, gives the film its asperity,” Durgnat says. “Since the affair didn’t matter much to him, it shouldn’t have mattered much to anybody.” Jack E. Cox’s fight cinematography is decades ahead of its time; ending a sports movie with an athlete utterly unconcerned about his defeat either literally in the ring or symbolically in the game of love would be a remarkable decision even today. Which also describes Kingsley Amis’s inspired substitution of apple spirits for grape ones in The Normandy and is the very definition of “timeless,” is it not?

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.