Starship Troopers was released on November 7, 1997. Three days later I turned 16. I don’t remember exactly how long after that it took me to earn my driver’s license, but there couldn’t have been much of a pause, because my friends and I saw it four times during its initial theatrical run. And so it was that this special effects extravaganza about an interstellar war against “the Bugs” became forever linked in my mind to both autumn and my childhood home of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. This month’s drink, the Witch’s Kiss cocktail from [Jim] Meehan’s Bartender Manual, honors that connection to the past through the saffron in Liquore Strega–it’s grown in southeastern PA, believe it or not–and updates it to the present via apple butter that I make with fruit from the tree in our backyard prepared à la Simply Recipes. Here’s what else is in the cocktail:

2 ozs. Cinnamon-infused reposado tequila (Espolòn)

3/4 oz. Lemon juice

1/2 oz. Strega

1/2 tsp. Agave syrup

1/2 tsp. Apple butter

To infuse the tequila, add a four-inch cinnamon stick to a one liter bottle and let stand for twenty-four hours, then remove. Shake all ingredients with ice, then fine-strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with a lemon twist.

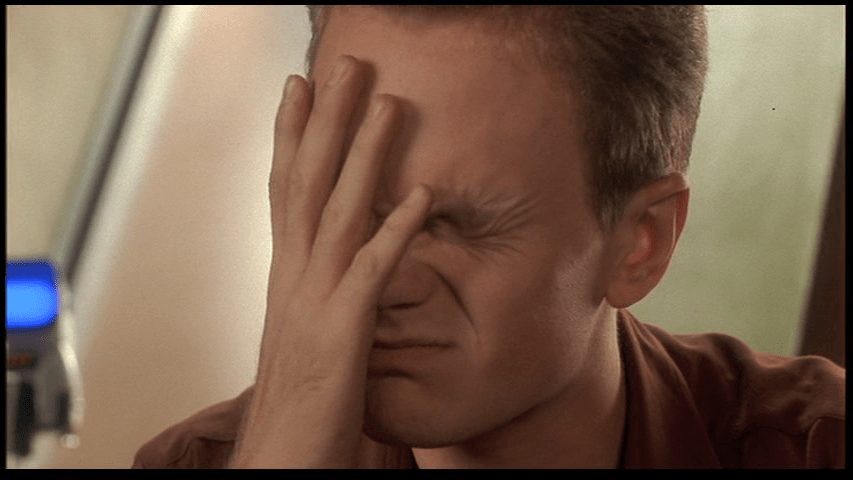

Per Meehan, “while tequila shines brightest in a summer Margarita, the aged bottlings mix beautifully with fall fruits and vegetables.” The Witch’s Kiss is case in point. The first impression is all apple-cinnamon with a touch of minerality from the Strega, but the Margarita vibes come through loud and clear on the finish: it’s autumn in a glass, but *early* autumn specifically. I’m not going to pretend that the drink has anything more than a purely associational connection to Starship Troopers, so here’s a picture of my Columbia Tristar DVD copy of the movie, which is still going strong after more than 25 years:

It’s also currently streaming on Netflix with a subscription and is available via a number of other platforms for a rental fee.

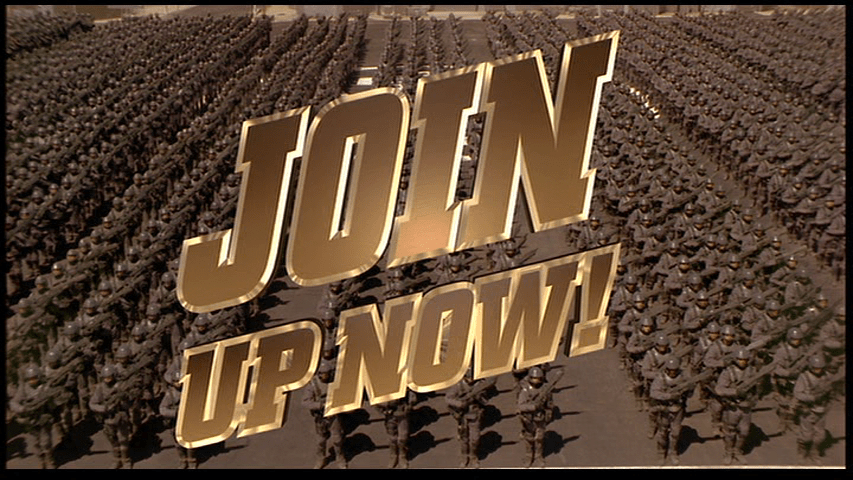

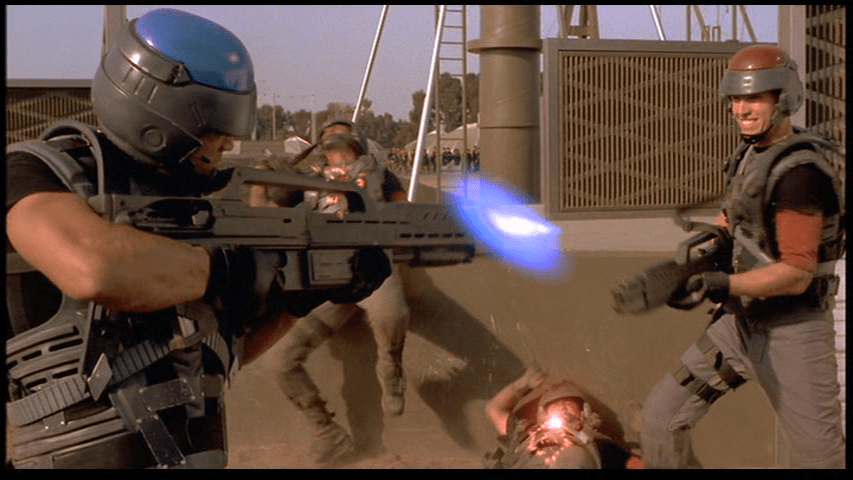

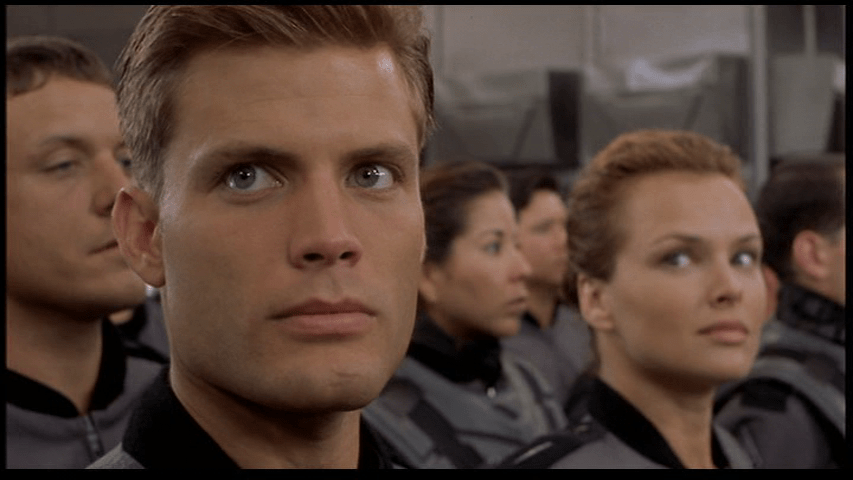

Starship Troopers begins with its most iconic recurring motif, a series of “Federal Network” newsreel-style vignettes which first implore the viewer to “do their part” and enlist:

Then celebrate new planetary defenses against “Bug meteors,” which are described in slightly greater depth when “we” use our cursor to answer the question “do you want to know more?” in the affirmative:

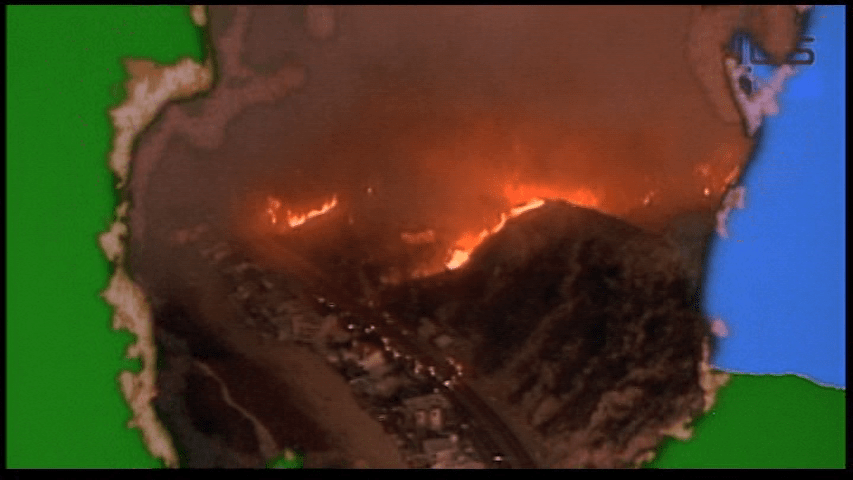

Before finally “breaking Net” to take us live to our adversary’s home planet of Klendathu, where an invasion is underway:

We cut to a reporter (Greg Travis) on the surface who soon gets ripped in half by a Bug warrior:

After which a human soldier named Johnny Rico (Casper Van Dien) addresses the camera and tells the person holding it to “get out of here now”:

Then himself appears to die in combat:

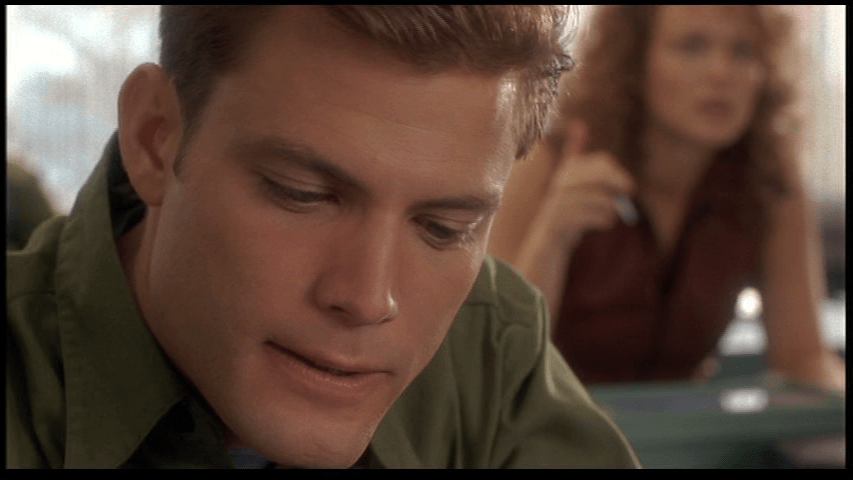

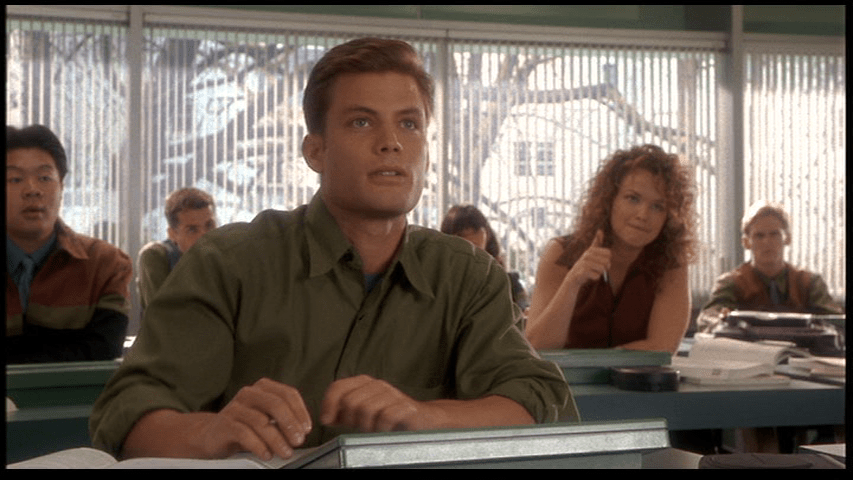

Static gives way to a title card reading “one year earlier,” which yields in turn to a shot of Johnny in school in Buenos Aires, where a teacher named Rasczak (Michael Ironside) redirects his attention from amorous doodles:

To a lecture summarizing the main points of the History and Moral Philosophy class which is about to conclude in a scene that Todd Berliner argues in his book Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema “contains perverse elements that complicate its genre identity and garble its ideological position.” As he explicates further:

The ideological perversity of the scene results from the fact that Rasczak is lecturing his students about the failure of democracy. He says that the present governing state, which separates people into “civilians” and “citizens,” has restored peace after years of strife caused by “social scientists of the 21st century.” He is describing, in short, a fascist utopia, a military state that affords citizenship only to those who serve in the armed forces.

No straightforward ideological proposition can make sense of the classroom scene because genre cues point in two opposing directions–making Rasczak look alternately like a liberal educator or a fascist ideologue.

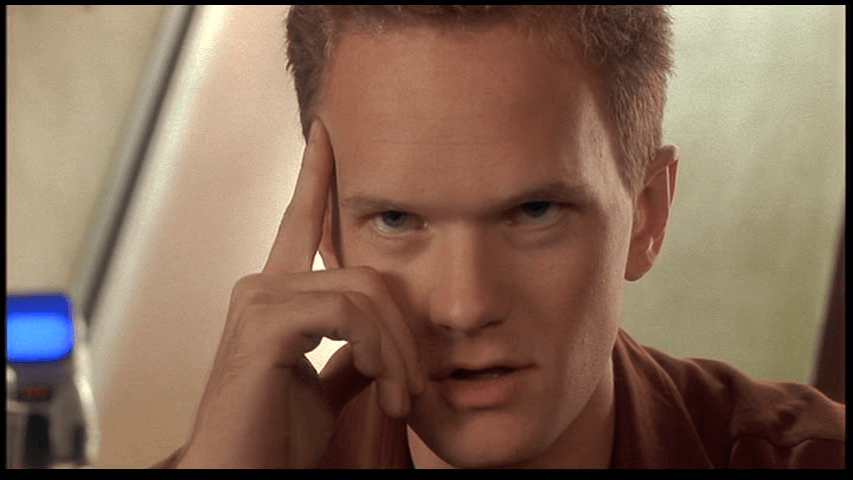

After the final bell rings, Johnny participates in a federally-funded research study testing for psychic abilities conducted by his best friend Carl (Neil Patrick Harris):

Wins the big game with this teammate Dizzy Flores (Dina Meyer), who has a crush on him:

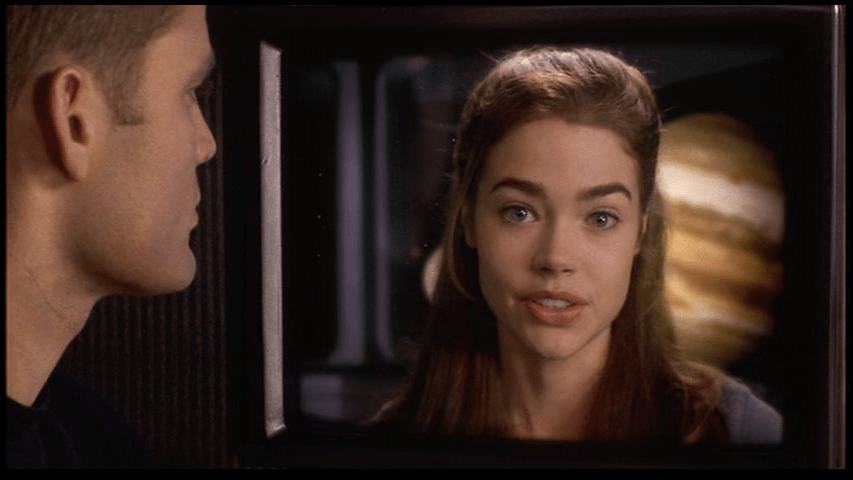

And goes to the prom with his girlfriend Carmen Ibanez (Denise Richards), an aspiring pilot who responds to him telling her that he, too, has decided to enlist even though it means his wealthy family will disown him by whispering “my father’s not home tonight” in his ear:

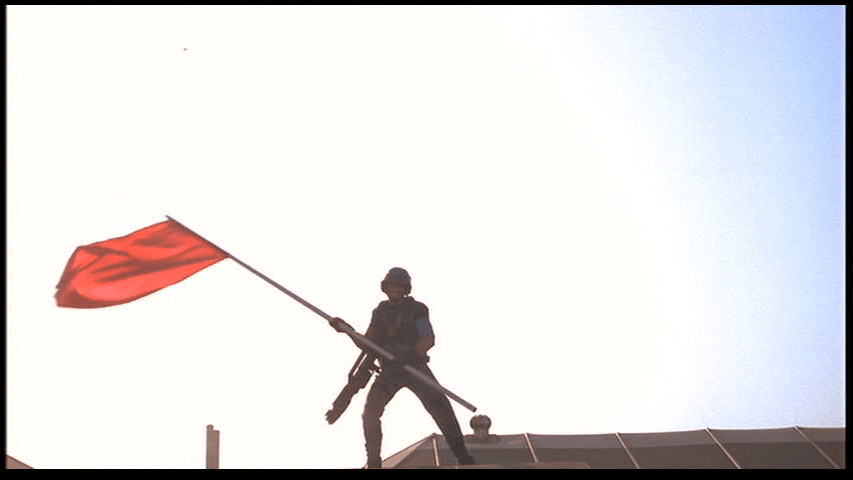

A long shot of them kissing during the last dance dissolves into a close-up of the flag of the Terran Federation, then the camera tilts down to show Johnny, Carl, and Carmen taking an oath:

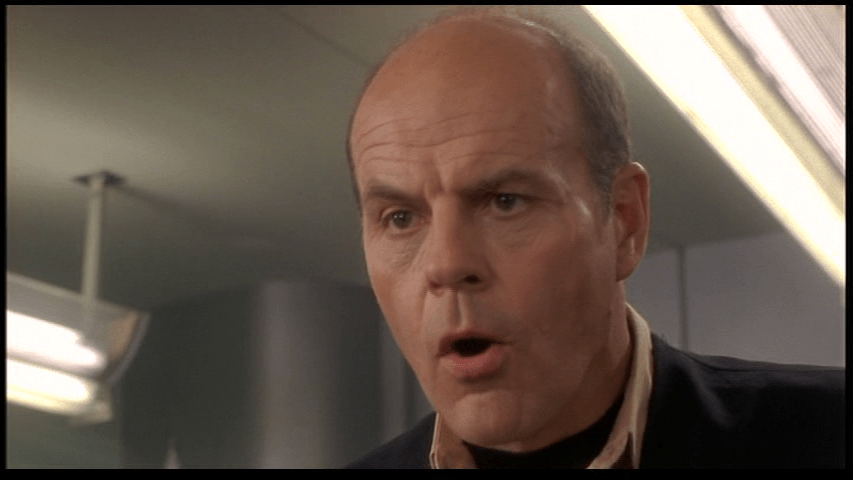

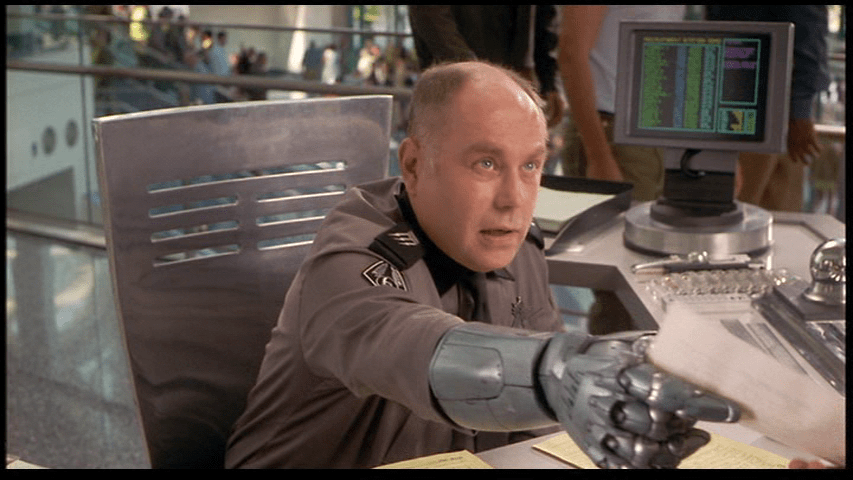

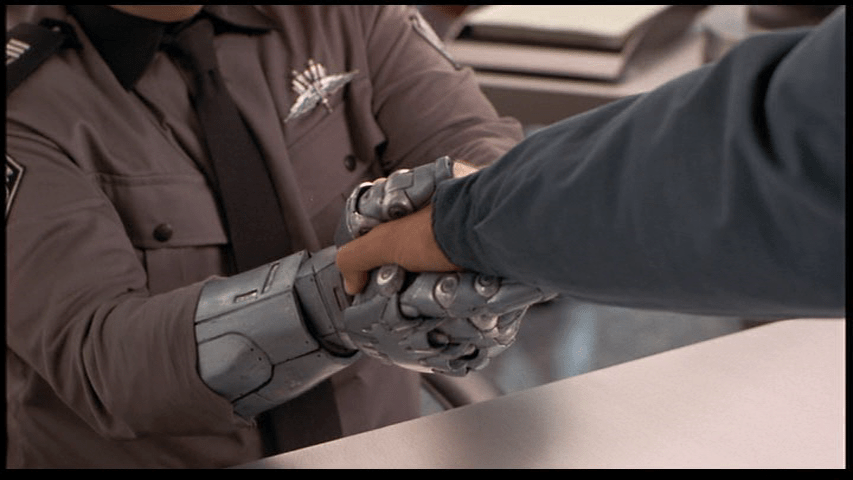

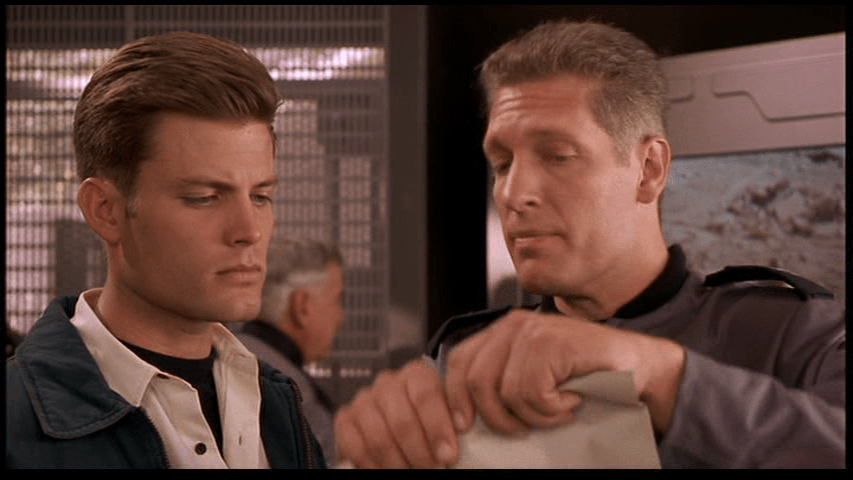

When a recruiting sergeant (Robert David Hall) with a robotic arm asks for their orders, we learn that Carmen has been assigned to Fleet like she hoped. Carl says he has been selected for Games & Theory aka military intelligence, to which the officer says, “next time we meet, I’ll probably have to salute you!”

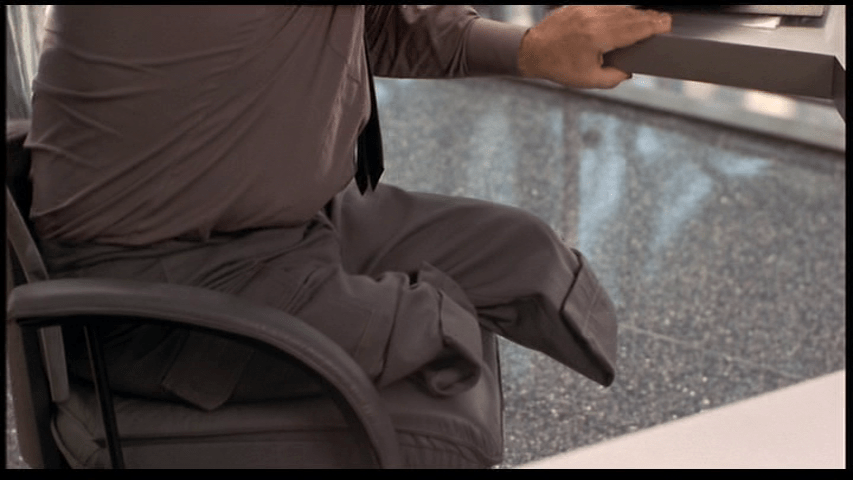

However, he reserves his strongest reaction for Johnny. “Good for you!” he exclaims when he finds out what branch Johnny will be going into, gripping his hand. “Mobile Infantry made me the man I am today.” Then he pushes his chair back to reveal that he’s also missing both of his legs.

Dizzy winds up at the same boot camp as Johnny and helps him earn the coveted title of squad leader by suggesting that they run one of their old football plays in a scene screenwriter Ed Neumeier identifies as an homage to The Dirty Dozen (which also featured war games between a blue team and a red team) on his DVD commentary track with director Paul Verhoeven:

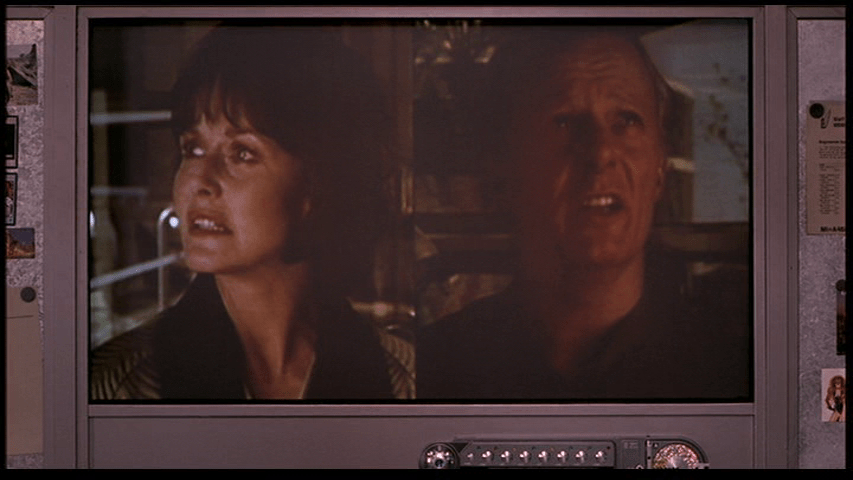

But Carmen dumps him in a video Dear Johnny (!) letter in the very next scene because she has decided to “go career”:

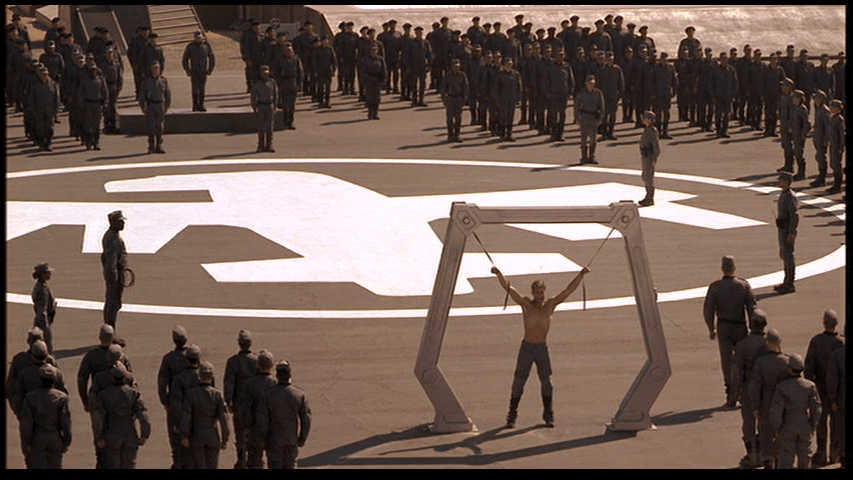

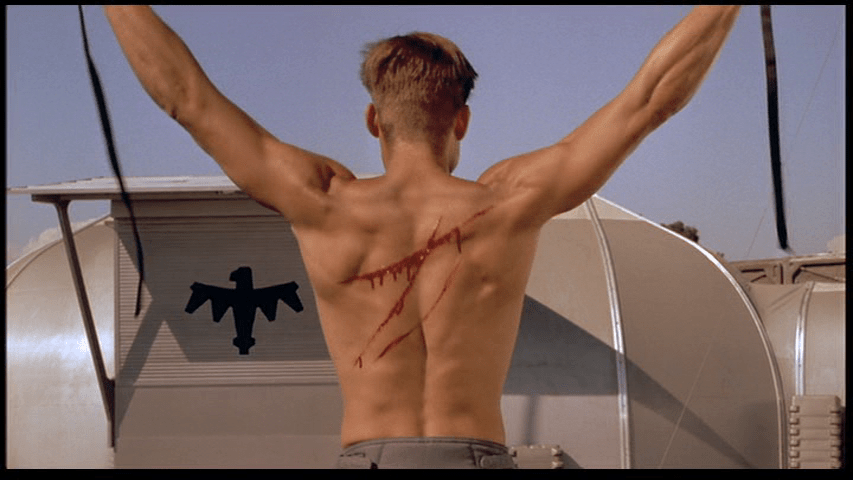

Then he is relieved of command of his squad following the death of a team member in a training accident and sentenced to “administrative punishment”:

After which he resolves to quit despite Dizzy telling him that it only proves he doesn’t “have what it takes to be a citizen.” His phone call home to deliver the good (from their perspective) news to his parents (Lenore Kasdorf & Christopher Curry) gets disconnected, though:

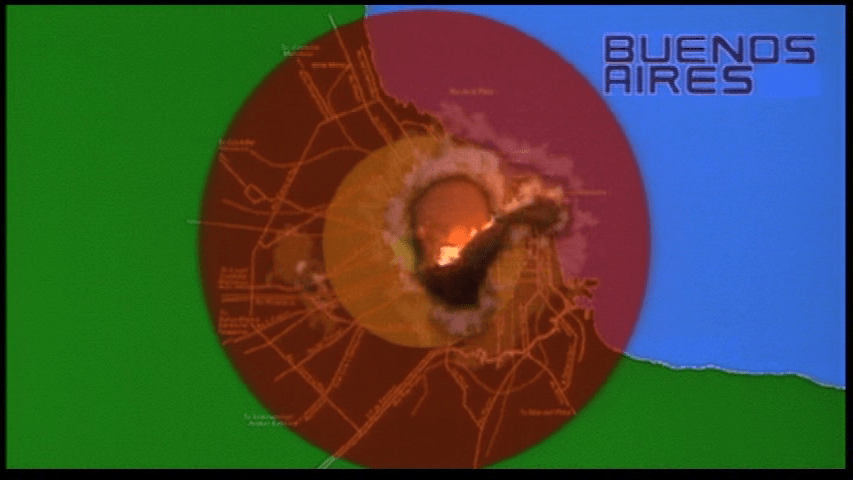

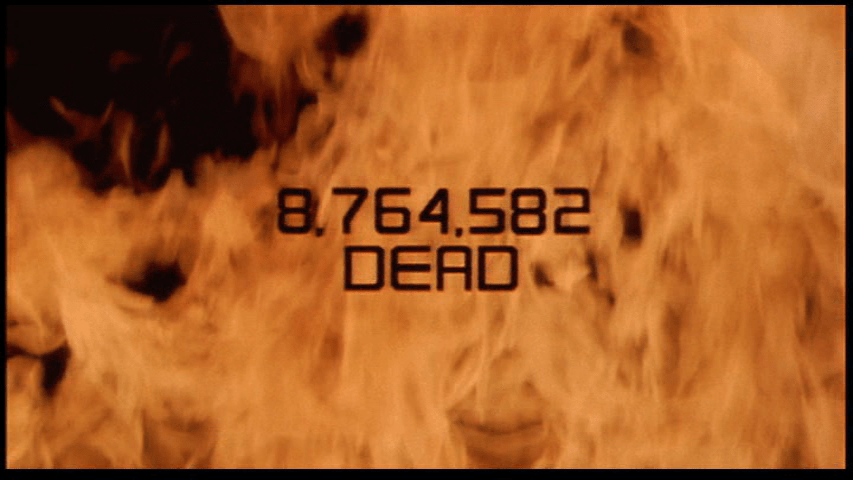

Moments later he learns why: Buenos Aires has been destroyed by one of those meteors we heard about earlier and the Federation is going to war.

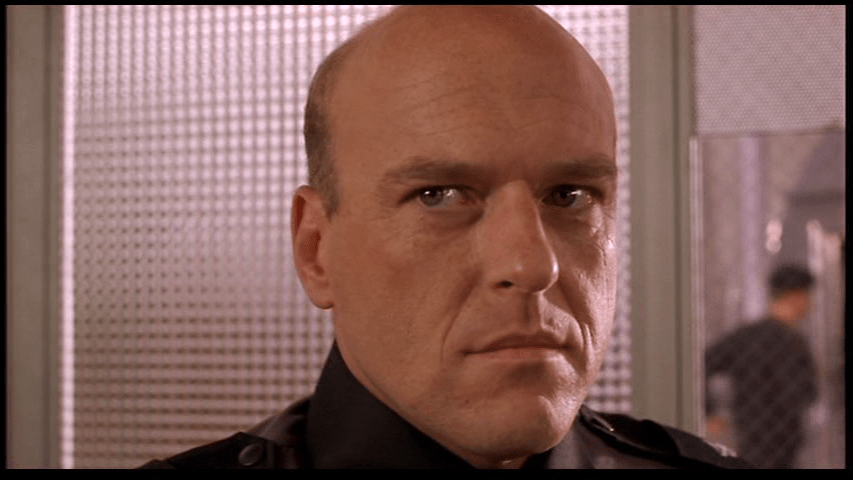

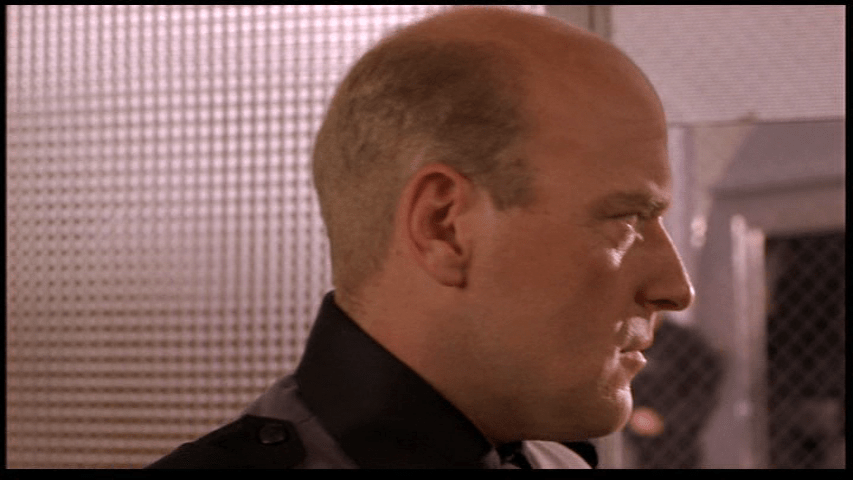

Johnny’s commanding officer (Dean Norris) looks the other way as his drill instructor Sergeant Zim (Clancy Brown) tears up his letter of resignation:

And following a FedNet sequence featuring a woman giddily clapping her hands and cheering as a group of children “do their part” by stomping on a bunch of presumably innocent insects:

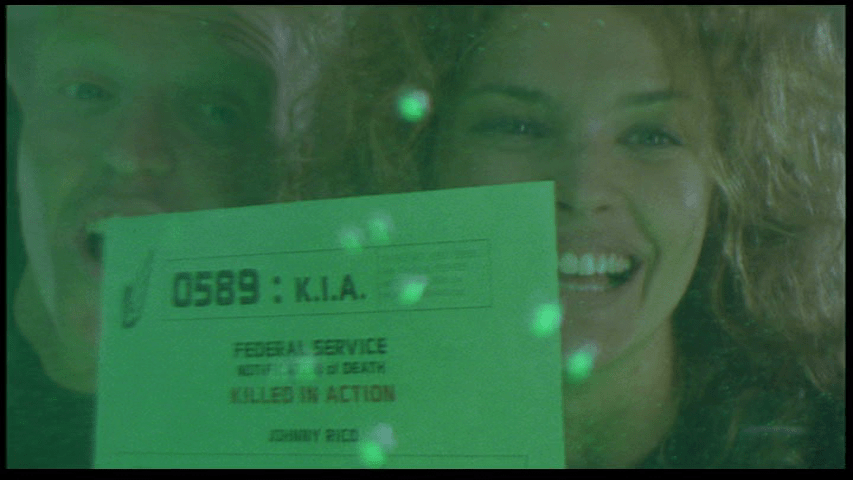

We find ourselves on “Fleet Battle Station Ticonderoga, deep inside the Arachnid Quarantine Zone,” where the men and women of the Federal Armed Services prepare to attack.” This is where we came in, as the fella says. Johnny survives, of course, even though official records list him as killed in action:

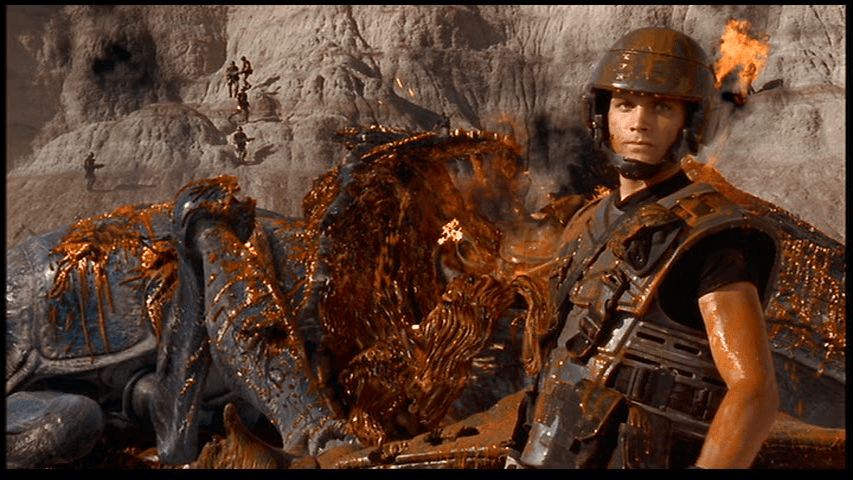

And the second half of the film chronicles the completion of his and his former classmates’ transformation from teen magazine idols into something harder and, especially in the case of Carl, who we last see decked out in garb that would clearly identify him as one of the bad guys if this was a World War II movie, verging on sinister.

In a chapter in the book The Literature/Film Reader: Issues of Adaptation, J. P. Telotte contends that a key difference between Starship Troopers the movie and the novel by Robert Heinlein it’s based on is that while the latter “is a first-person narrative told from Johnny Rico’s vantage point, Verhoeven’s film unfolds, not from the perspective of any individual, but rather from the point of view offered by the audiovisual culture itself,” which enables it to “establish a rather different authoritarian voice, and indeed a subtly tyrannical power, one that is the real heart of its satiric vision.” Andrew O’Hehir said something very similar in his remarkably astute contemporaneous review for Sight & Sound, noting that while Heinlein’s “fascist-flavored Utopia” was “a deadly earnest prescription,” in Verhoeven’s hands “it becomes an aesthetic and ideological field of play.” They’re thinking not just about the FedNet sidebars which explicitly reference historical propaganda pieces:

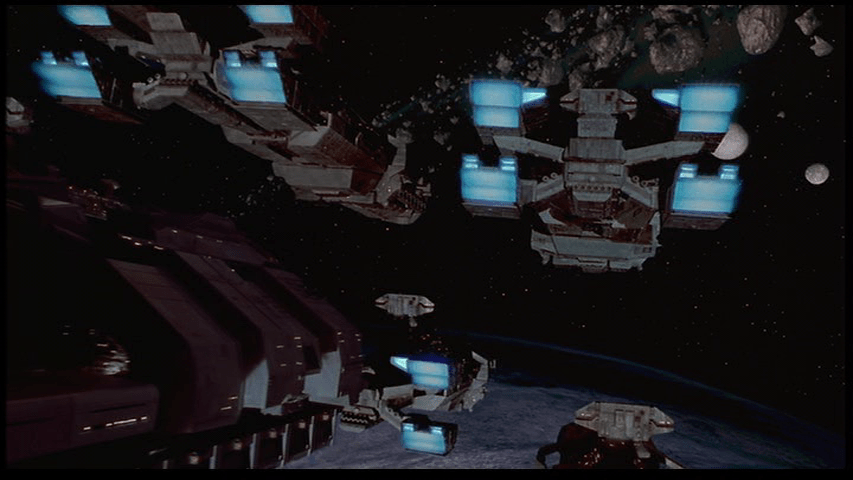

And are also, as Neumeier explains in his DVD commentary, “meant to evoke CNN coverage of the Gulf War,” but the rest of the film as well. I think it only really works if you sincerely enjoy it on its own merits for the amazingly undated special effects in scenes like the wreck of Carmen’s ship the Rodger Young:

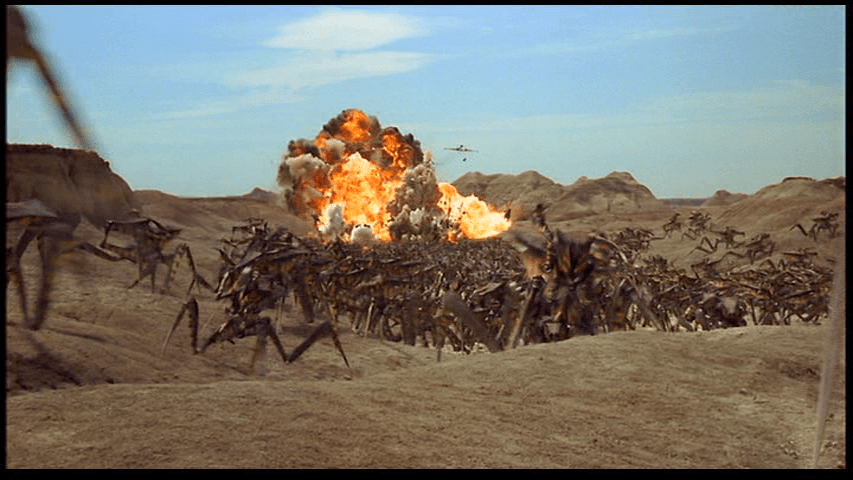

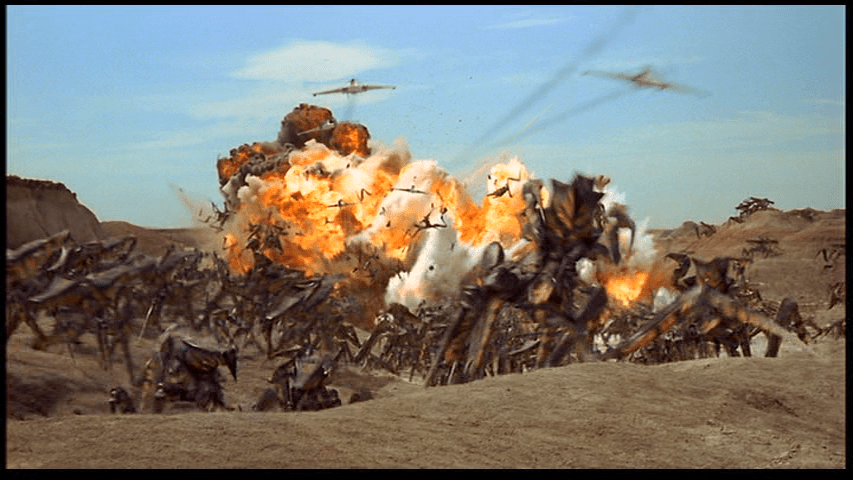

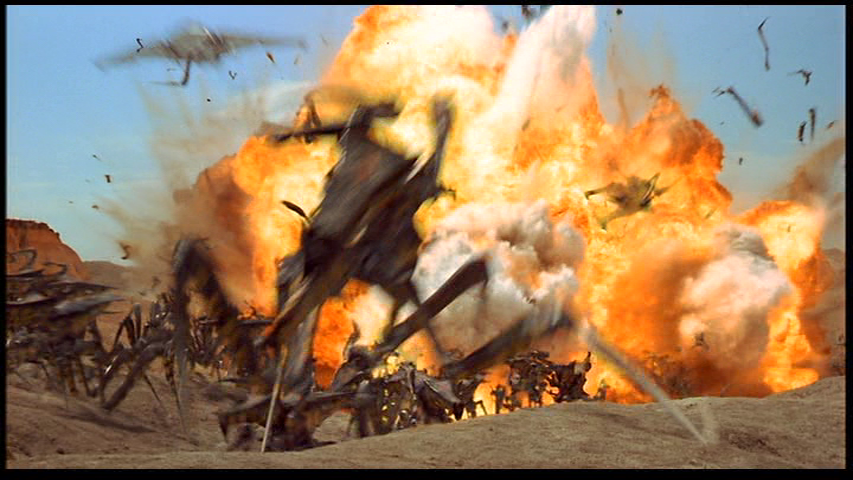

And the attack on Planet P which surely must have been inspired by the movie Zulu:

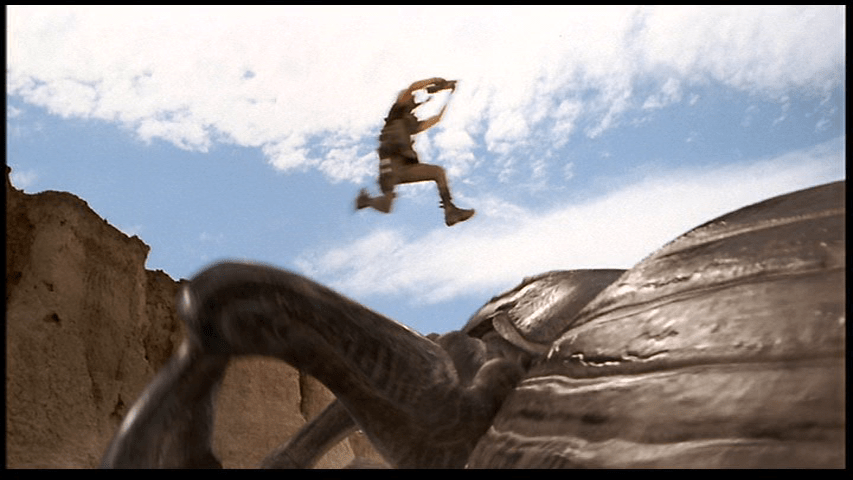

Action sequences like Johnny single-handedly taking out a giant “Tanker” Bug with a grenade:

And endlessly-quotable lines like a panelist on a Crossfire-like program (Timothy McNeil) declaring, “frankly I find the idea of a bug that thinks offensive”:

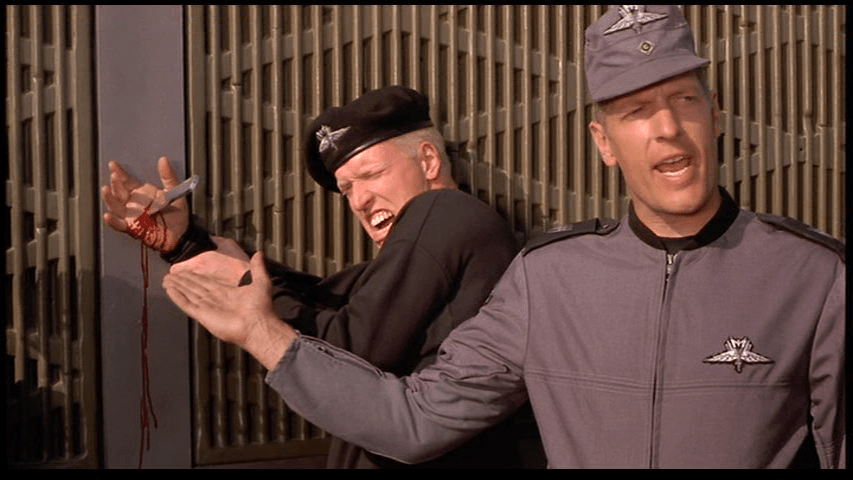

And Sergeant Zim answering a question from Johnny’s skeptical fellow trooper Ace Levy (Jake Busey), about the utility of hand-to-hand combat in an age of nuclear weapons by pinning his hand to a wall with an expertly-thrown knife and declaring, “if you disable the enemy’s hand, he cannot push a button!”

I do, obviously, and that’s why, like Jamelle Bouie, I’m able to read it as an artifact “made by the human government of the film to rally the populace in a losing war against the Bugs” (which a footnote in this 2001 journal article by Lene Hansen indicates was supported by the film’s no-longer-extant late-90s website) or, as O’Hehir suggests, a fable from an alternate universe in which Hitler won. I am genuinely moved by Johnny and Dizzy’s surprise when they discover that their new Lieutenant is their old teacher:

Johnny’s eulogy for Dizzy after she dies in his arms:

And his reaction to hearing his unit described as “Rico’s Roughnecks” for the first time after he assumes command when Rasczak also dies in combat:

Because I am moved, I am also disturbed; because I am disturbed, I am on my guard against being manipulated by these same techniques in other contexts.

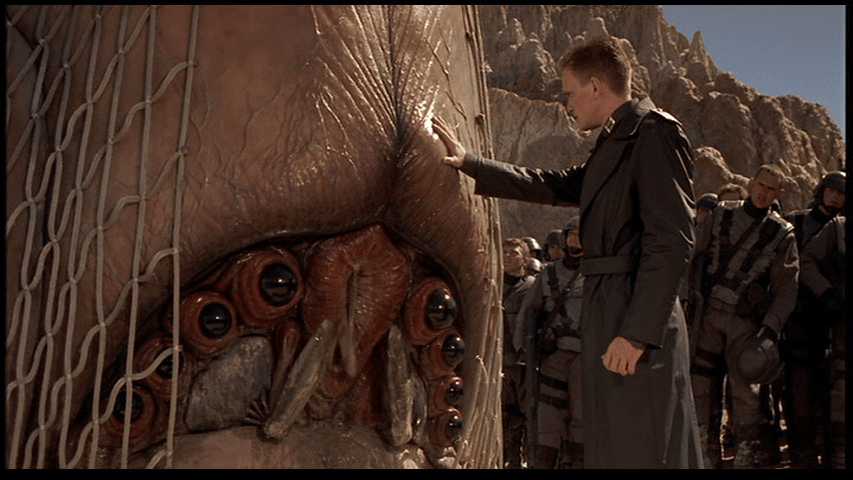

Telotte notes that for all its deviations from the book it’s adapted from, “the film still follows the Heinlein pattern of youthful education, in large part because, the movie implies, we have all become very much like juveniles in the process of being molded by today’s media culture.” This strikes me as similar to Neumeier’s commentary track observation that “Carl has become like an insect here” when the image above of him placing his hand on the “Brain Bug” Sergeant Zim has captured to read its mind appears on the screen. Early in the film, Carmen pushes back against a teacher’s (Rue McClanahan) statement that insects are superior to us in many ways on the grounds that “humans have created art, mathematics, and interstellar travel.”

The rebuttal focuses just on the third item on this list, but as O’Hehir points out, “for all the movie’s humans know, there are arachnid poets greater than Milton.” This is where Starship Troopers *really* starts to get interesting for me. While also still in school, Carl refers to his psychic abilities as “a new stage in human evolution,” which reminds me of two of my previous Drink & a Movie selections: Crimes of the Future, which regards such a possibility in a positive light, and Stalker, which is more circumspect. Neumeier means to criticize Carl by comparing him to an insect, but as Ed Howard observes in a 2009 blog post, his director “focuses equally on the casualties of humans and aliens alike” and “keeps subtly reminding his audience that the aliens are not simply expendable cannon fodder,” for instance in this scene where “Verhoeven’s composition deliberately recalls popular representations of the Pearl Harbor attack and of American napalm bombing raids in Vietnam”:

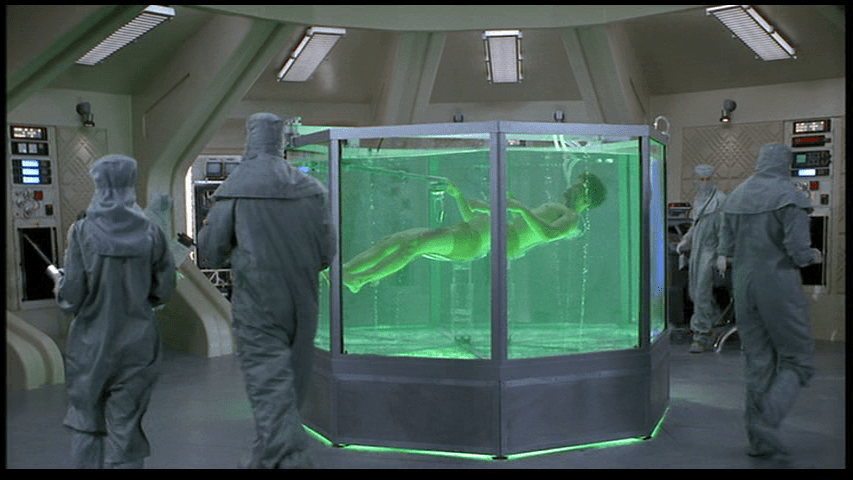

Similarly, although O’Hehir is right that “of course, we’ll root for the human race against a teeming hive of insects,” scenes like this:

And this:

Nonetheless inarguably constitute torturing prisoners of war, and our species’ reaction to Carl’s triumphant announcement that the captured Brain Bug is afraid is also shameful:

Heinlein obviously intends insect society as a metaphor for America’s Cold War Communist enemies; Neumeier and Verhoeven flip this around and equate the Bugs with fascism. More important than specific ideologies, though, is the universal truth that the harder you try to vilify a supposed enemy, the likelier it is that you will come to embody their “worst” tendencies yourself. Or to quote another movie I saw in high school, 8MM, “if you dance with the devil, the devil don’t change–the devil changes you.”

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka my loving wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.