We planted red shiso in our herb garden a couple of years ago as a novelty. It unexpectedly came back the following spring and basically took over, which we soon discovered poses a bit of a challenge because it has such a distinctive color and flavor that most recipes you find it in use only a small quantity, so it’s hard to dispatch in bulk. Luckily, although it still pops up all over our yard, the amount competing for space with other edible plants is now more or less under control and it has returned to being a valued occasional guest on our summer meal plans in dishes like Marc Matsumoto’s twist on capellini pomodoro and as one of the “fresh tender herbs” in our house salad dressing, Food & Wine magazine’s whole lemon vinaigrette.

Like the mint we also grow, though, the place it really shines is a drink component and garnish. Our favorite such beverage is the Shady Lane from Brad Thomas Parsons’ Bitters book, which has long been part of our home mixology library but somehow hasn’t yet made an appearance on this blog. Here’s how to make it:

1 1/2 ozs. Gin (Roku)

3/4 oz. Lillet Rouge

1/2 oz. Blackberry-lime syrup

1/2 oz. Lime juice

2 dashes Scrappy’s Lime bitters

3 Blackberries, plus more for a garnish

3 Shiso leaves, plus more for a garnish

Club soda

Make the blackberry-lime syrup by combining one cup of blackberries with one cup each of sugar and water and the zest of two limes and bring to a simmer, stirring occasionally and mashing the berries with a wooden spoon. Remove from heat, cool completely, and strain, reserving the solids. To make the cocktail, muddle the blackberries and shiso leaves in the bottom of a shaker with the syrup. Add ice and all of the other ingredients except the club soda and shake, then strain into a chilled rocks glass. Top with club soda and garnish with additional blackberries and a shiso leaf.

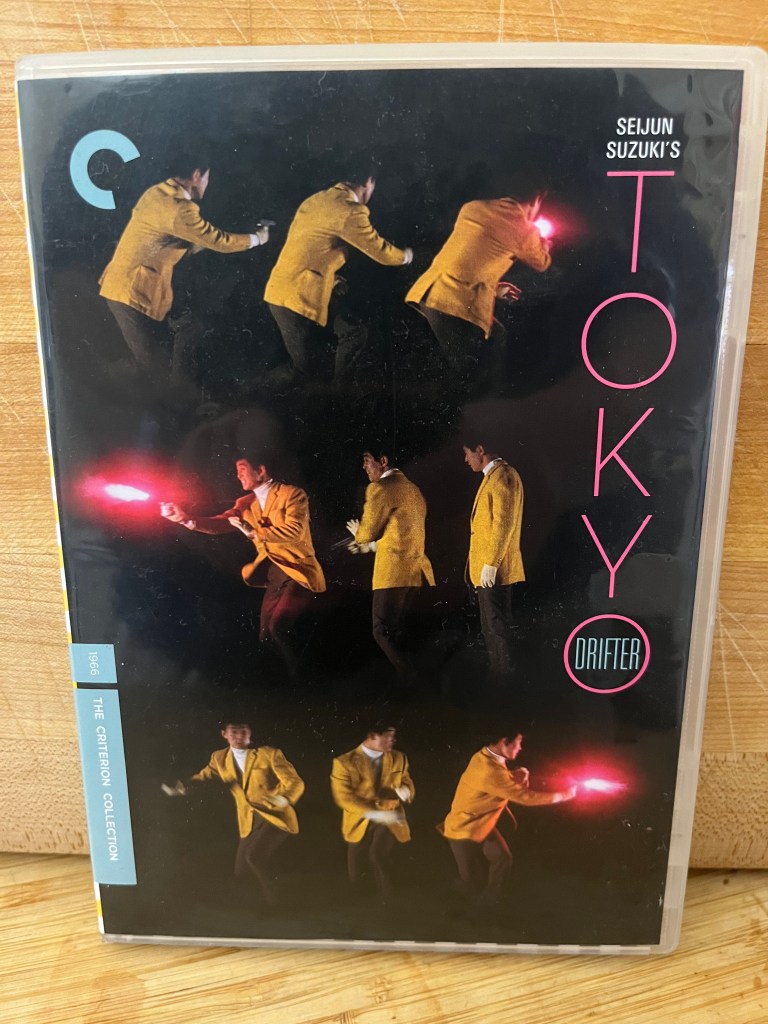

First off, despite what Parsons says, DO NOT DISCARD THE SOLIDS AFTER MAKING THE SYRUP: hey are absolutely delicious with yogurt and granola! Shiso is a difficult flavor to describe to people not already familiar with it. Writing for the New York Times in 1995, Mark Bittman went with “it has a mysterious, bright taste that reminds people of mint, basil, tarragon, cilantro, cinnamon, anise or the smell of a mountain meadow after a rainstorm,” which, sure, I guess, but the quote by Jean-Georges Vongerichten four paragraphs later also gets the job done: “I like it a lot.” Whichever way you want it, that’s what dominates the first sip of a Shady Lane, but this immediately slides gracefully into dark fruit, lime zest, and juniper. The drink’s balance is absolutely perfect–it doesn’t register as particularly sweet or tart–and the effervescence from the club soda and spiciness of the Japanese gin make it a great summer sipper. Parsons explains that he named this concoction after the classic Pavement song, so it would be a great choice to pair with the film about them that recently debuted on Mubi, but its brilliant purple hue reminded me of the garish colors of Tokyo Drifter, so that’s what we’re going with. Here’s a picture of my Criterion Collection DVD copy:

It’s also currently streaming on the Criterion Channel with a subscription and available via a number of other platforms for a rental fee.

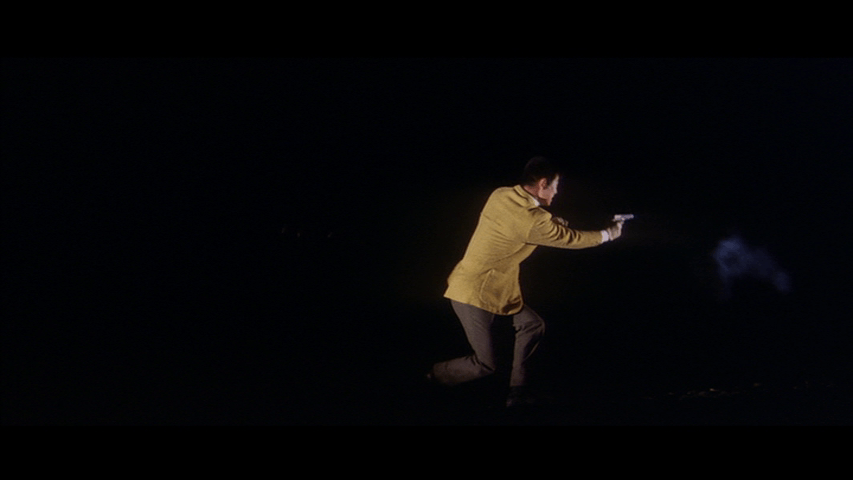

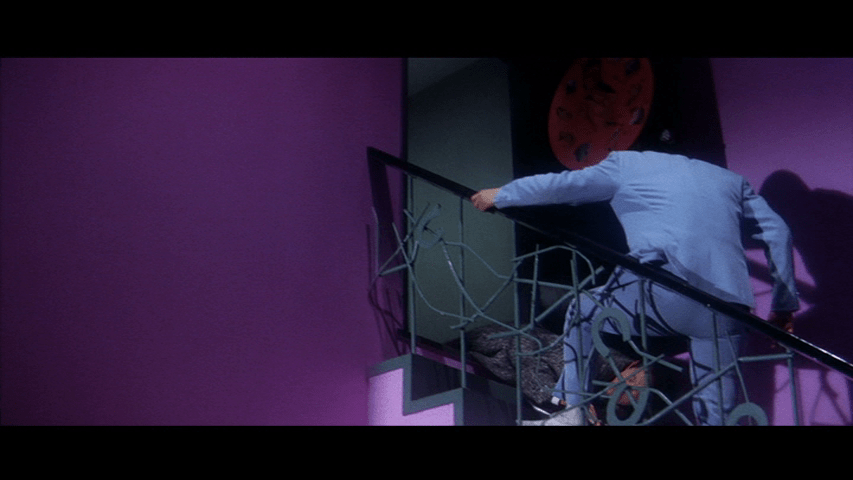

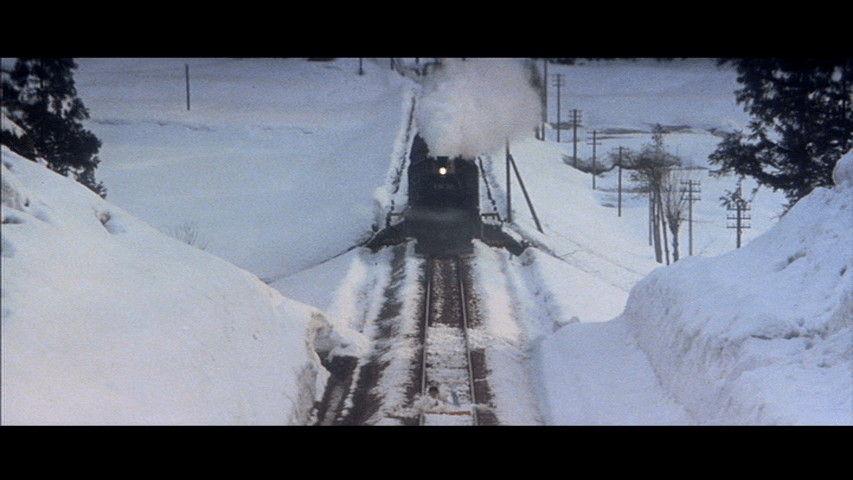

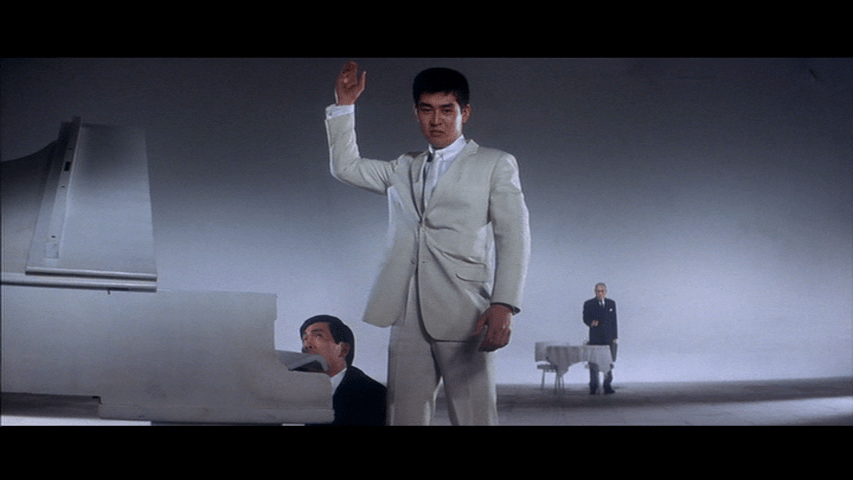

As Tom Vick writes in his book Time and Place are Nonsense: The Films of Seijun Suzuki, “Tokyo Drifter begins with a gesture more at home in experimental than commercial cinema: grainy, high-contrast, black-and-white opening scenes that were shot on expired film stock.” A man wearing a light-colored suit with white shoes and gloves walks toward the camera along a railroad track:

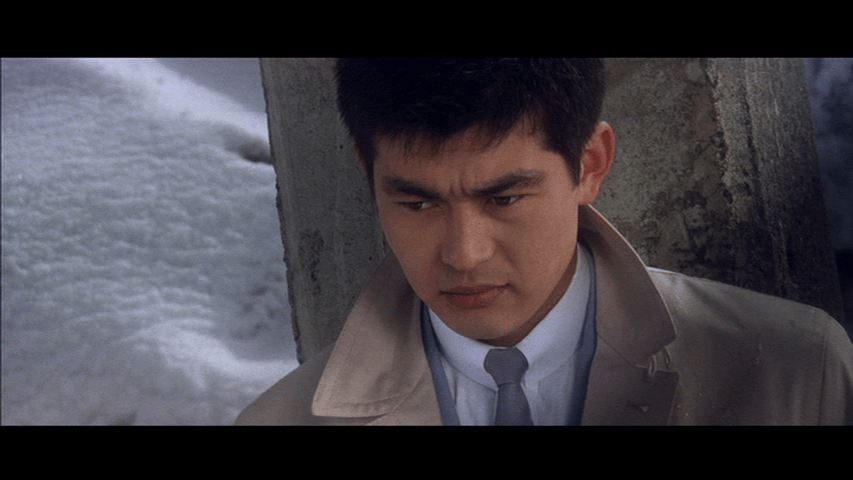

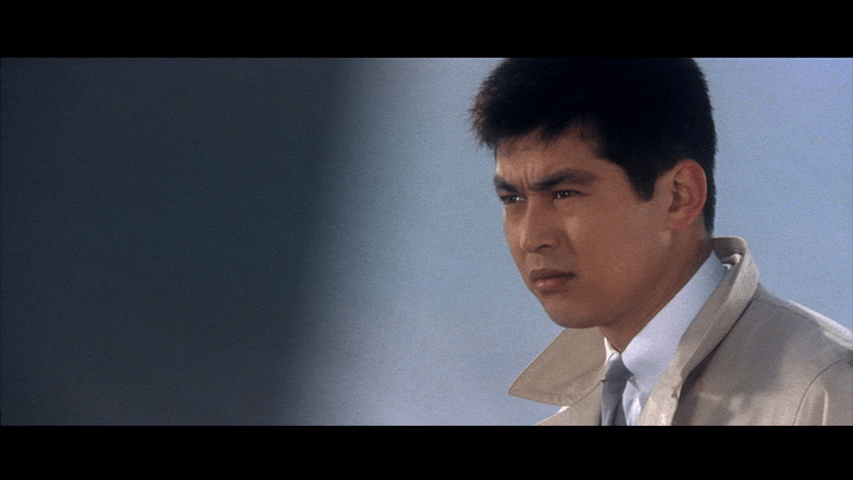

He is “Phoenix” Tetsu (Tetsuya Watari) and until recently none dared mess with him or his yakuza boss Kurata (Ryûji Kita). They’ve gone straight, though, and Kurata’s rival Otsuka (Eimei Esumi) has decided to test Tetsu’s resolve by ambushing him:

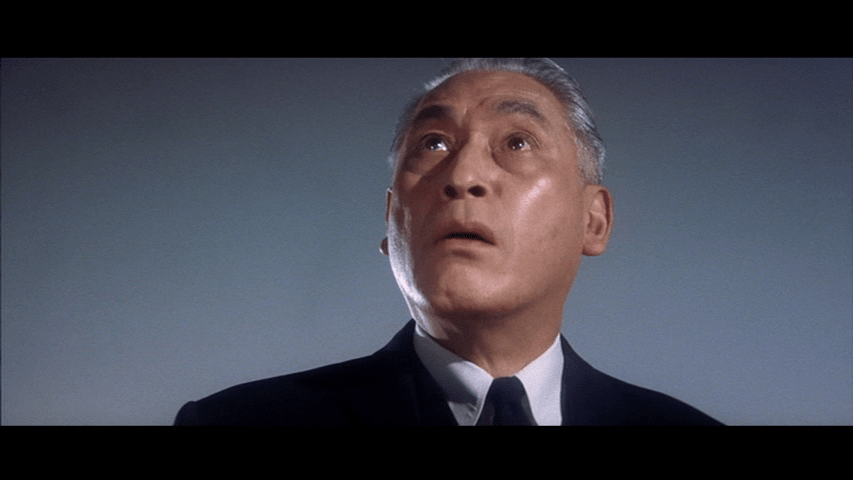

Otsuka watches from a nearby car:

And predicts that Tetsu will “get knocked down three times, then rise up like a hurricane” in a voiceover that accompanies the brief color fantasy sequence that Criterion chose as the basis for their cover art:

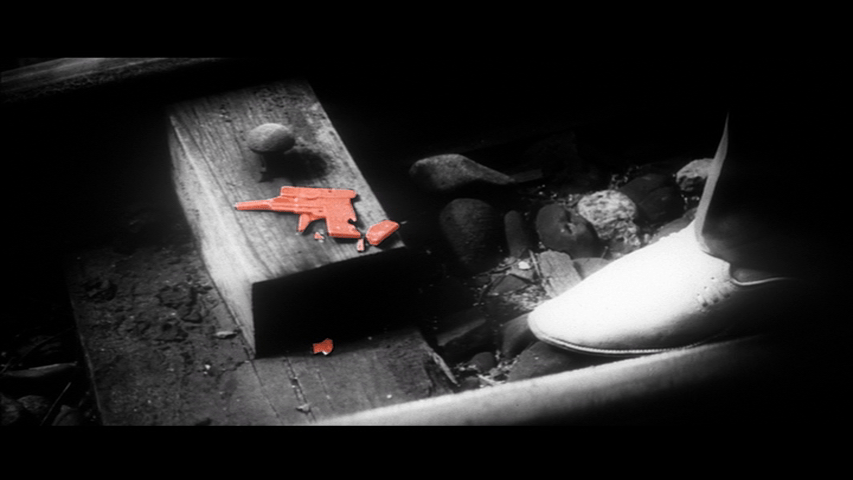

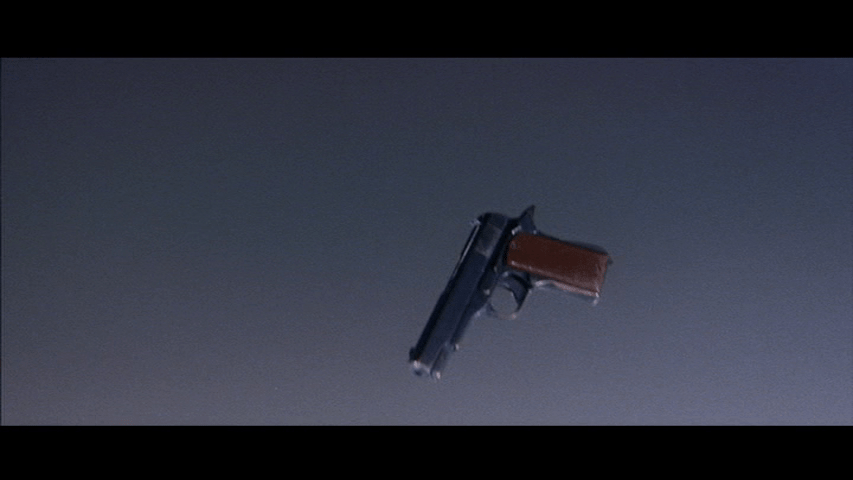

But when Tetsu stubbornly refuses to fight back he says, “I see. So we can do anything we want.” The sequence ends with another splash of color when Tetsu, having staggered to his feet after his beating, looks down and spies a broken gun which is obviously a prop and glows red against a monochrome background:

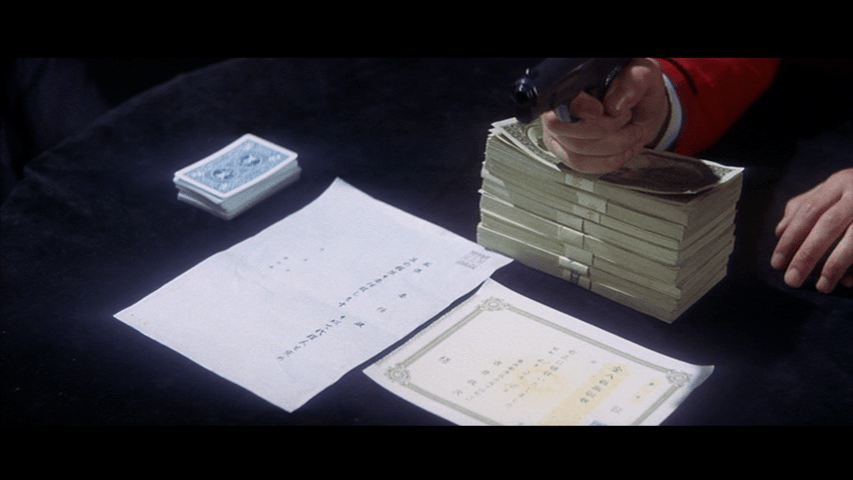

Which Peter Yacavone contends “promotes a consciousness of cliché” in his book Negative, Nonsensical, and Non-Conformist: The Films of Suzuki Seijun. Whatever Otsuka wants turns out to be stealing a building from Kurata by forcing his business partner Yoshii (Michio Hino) to sign a sizeable debt over to him at gunpoint:

Then shooting him:

Tetsu arrives moments too late to help:

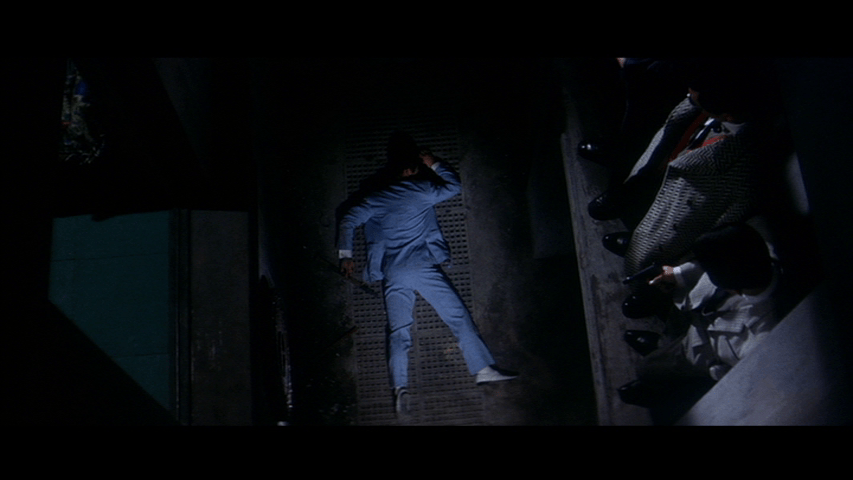

And is knocked out in the skirmish that follows:

He revives in time to save Kurata from signing over the building to Otsuka:

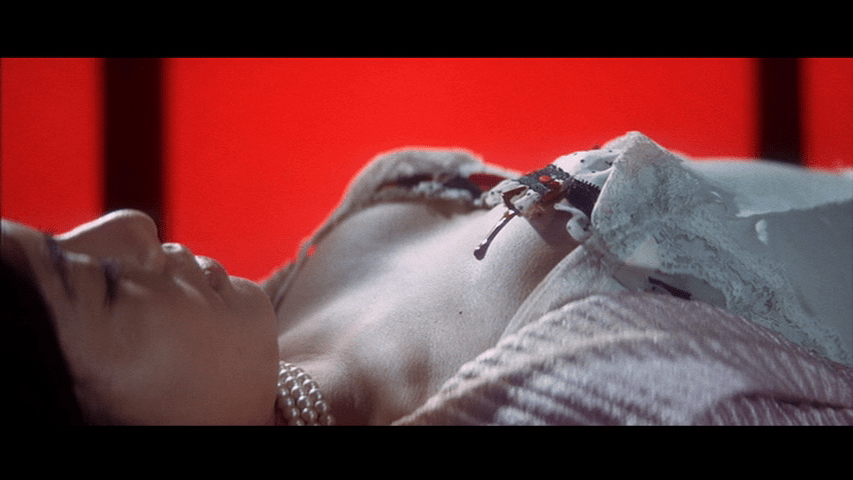

But not before Kurata accidentally kills Yoshii’s secretary Mutsuko (Tomoko Hamakawa) while trying to shoot Otsuka:

Tetsu confronts Otsuka’s henchman Tatsu “the Viper” (Tamio Kawachi) in a junkyard sequence that includes a largely gratuitous depiction of a car being demolished:

As well as Tetsu singing the movie’s insanely catchy titular theme song:

Tetsu informs Tatsu that he intends to take the rap for Mutsuko’s murder should Otsuka attempt to finger his boss, and that if he is arrested he’ll let the police know who killed Yoshii. Otsuka responds by sending an emissary to Kurata to propose a trade: if he hands over Tetsu, they’ll return the deed to his building. He refuses:

And moved by his gesture, Tetsu, who overheard the conversation, decides to leave town:

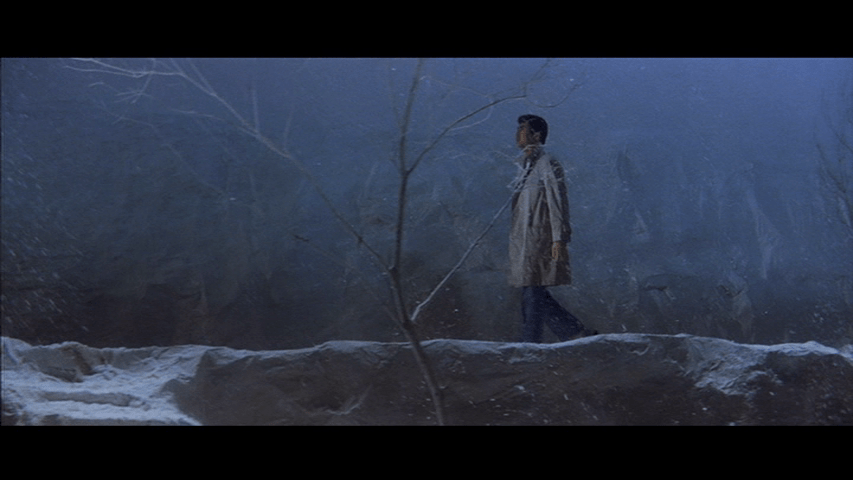

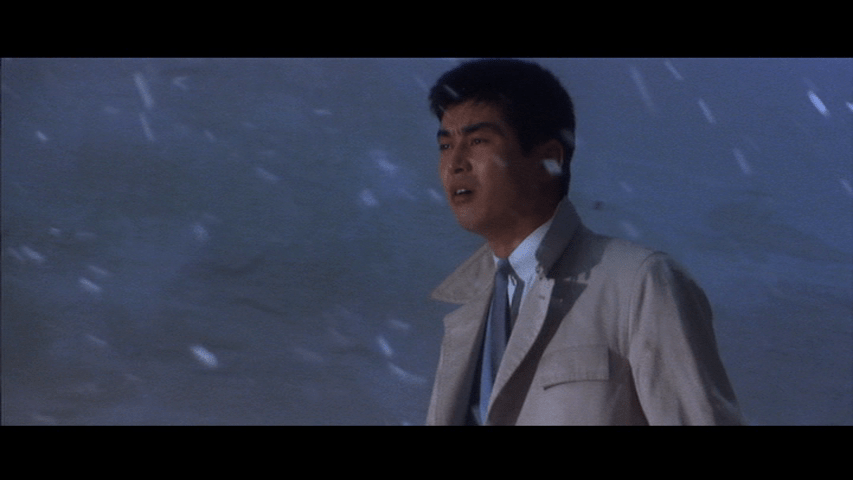

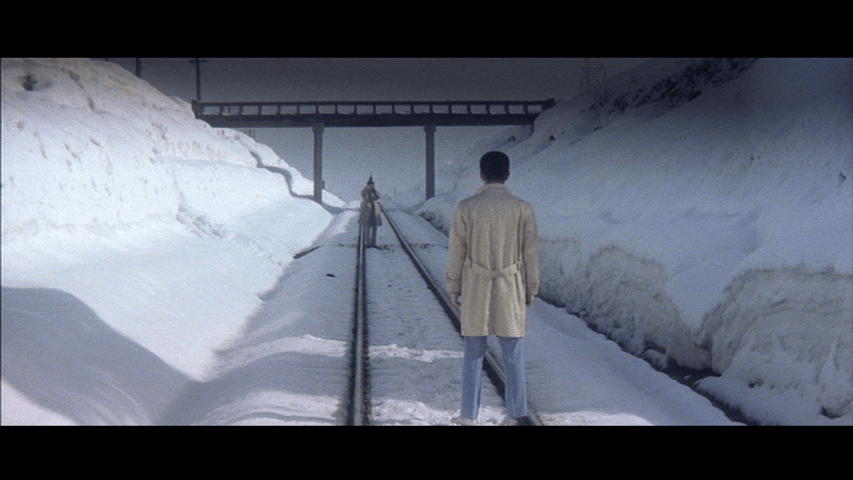

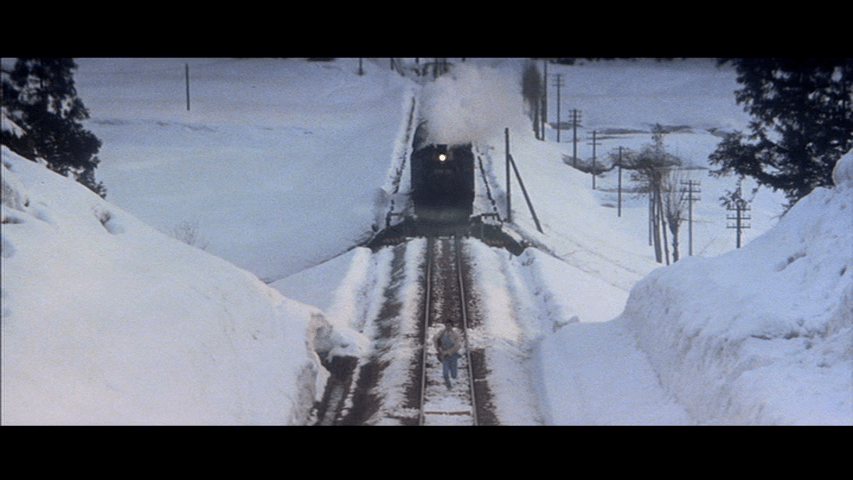

Tony Rayns, writing in the book Branded to Thrill: The Delirious Cinema of Suzuki Seijun, argues that “the ultimate fascination of Tokyo Drifter is that despite the apparently wilful ‘deconstruction’ of the genre, it none the less works as a thriller.” One great example of both parts of this proposition is a duel fought in front of a train speeding down on the combatants shortly after Tetsu arrives in Shonai, home of one of Kurata’s allies, with Otsuka’s men hot on his heels. When they attack he signals his presence by again singing the film’s theme song as he walks through the snow:

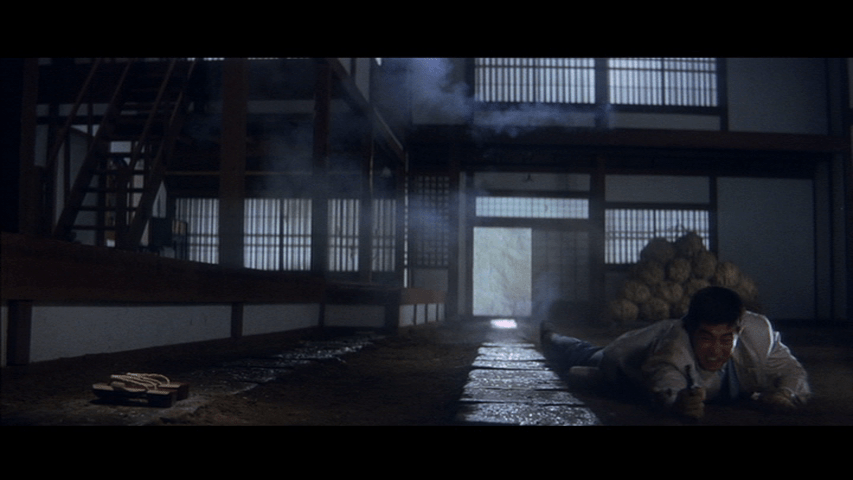

Then joins the fray. As he takes cover behind some bales of hay, voiceover narration signals his thoughts: “my range is under ten yards.”

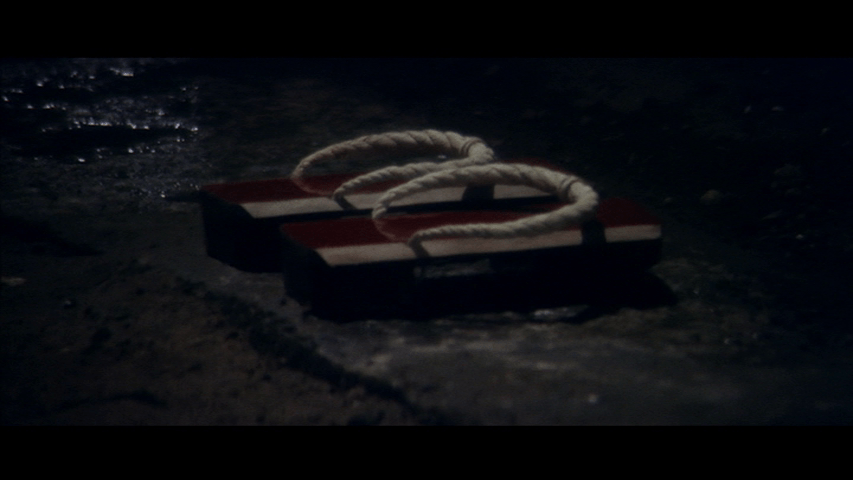

Suddenly, he spots a pair of geta in a shaky cam POV shot:

The idea, of course, is that they are ten yards away from Tetsu’s enemies, which explains why he leaps toward them moments later:

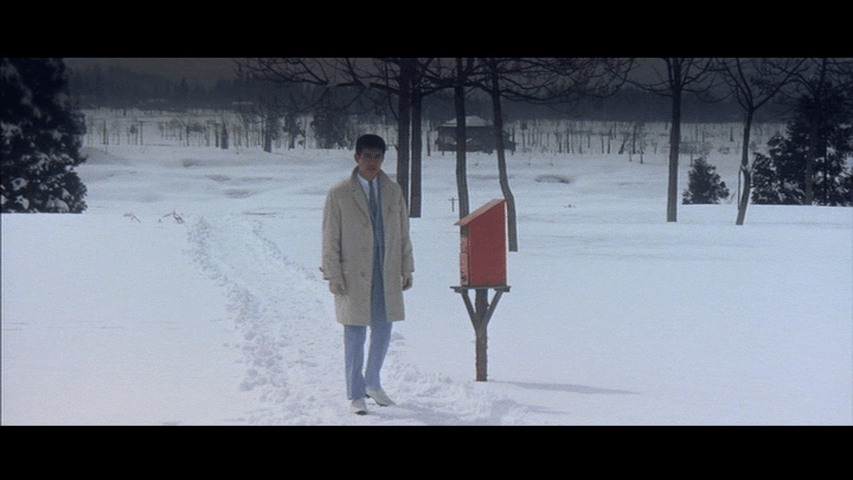

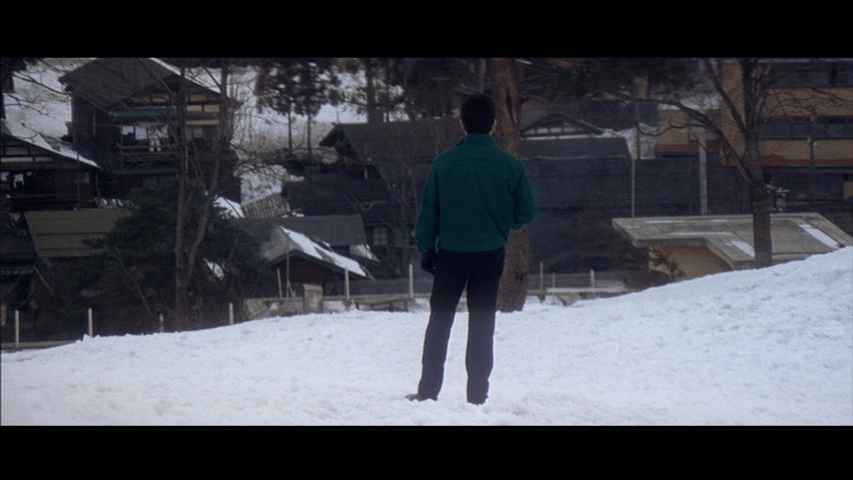

Fast forward to the next scene. It begins with Tetsu trudging through a field covered in snow, which cinematographer Shigeyoshi Mine and production designer Takeo Kimura identify as the movie’s true protagonist in a delightful anecdote about an alcohol-fueled creative session by director Seijun Suzuki that I’m grateful to Vick for including in Time and Place are Nonsense:

Kimura has confidence in Mine’s talent, with whom he is able to create an image like a sumi-e [a traditional ink-wash painting]. But the characters of the two men do not harmonize well. Mine is impulsive, Kimura is complex. One trait they have in common is that they are both egotists. … When they are drinking sake, their ego emerges with greater force. …They discuss the photography of [Tokyo Drifter], in which the snow is the protagonist of the story. I’m being canny. I wait until they stop arguing. Sometimes they turn to me, but I don’t respond, because for me it is enough to decide at the time when the camera has to be set up. The snow already has provoked something in these men, whichever image of the snow will eventually transpire.

Anyway, as Tetsu walks he realizes he’s being followed:

No explanation is offered for either the way he vanishes from his pursuer Tatsu’s sight in between shots or the apparently nondiegetic triangular shadow that appears at the same time:

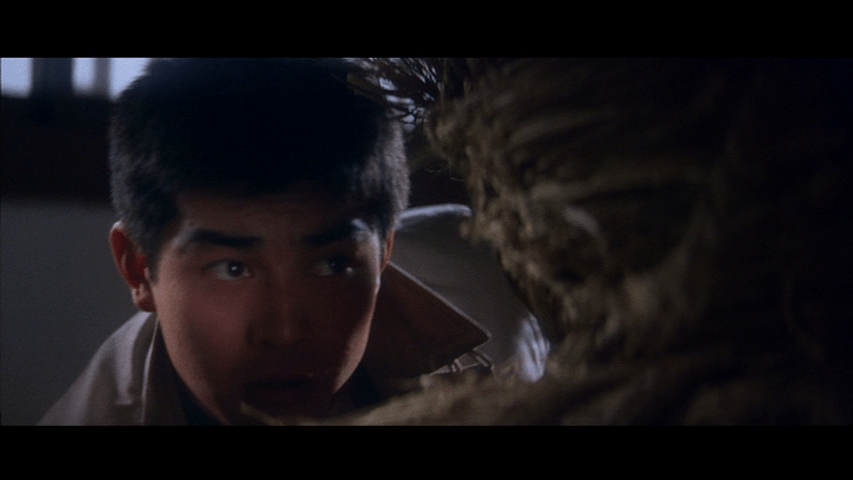

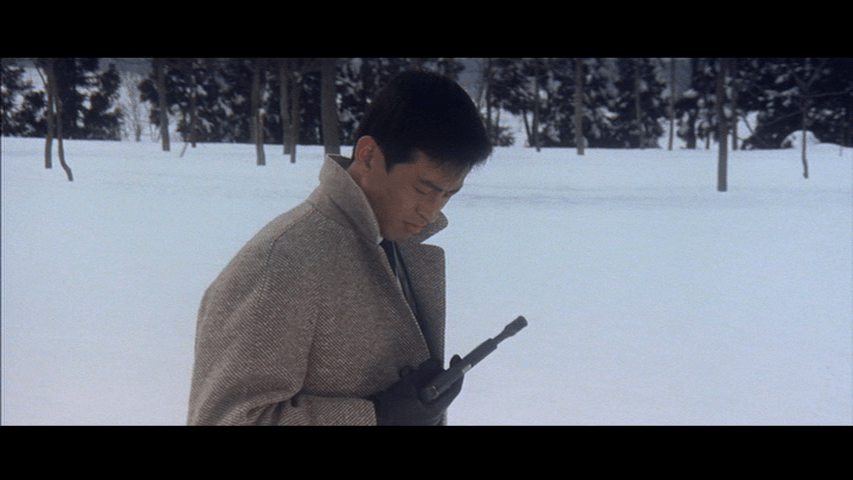

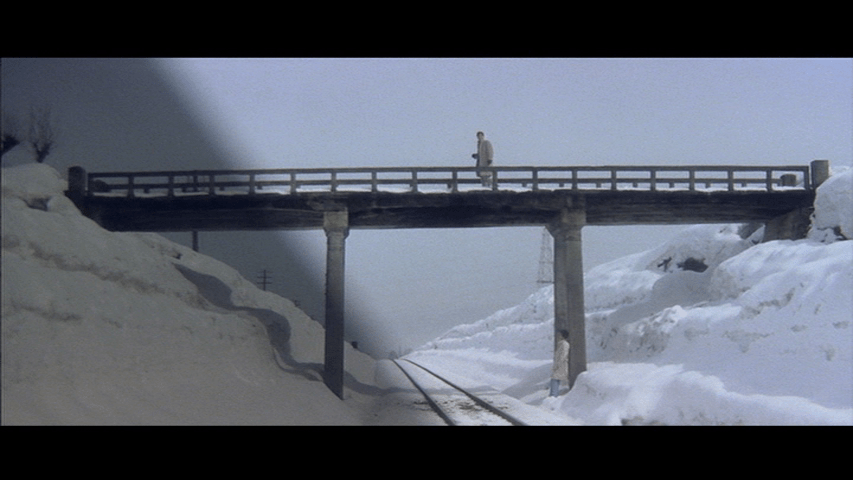

But the next thing we know Tetsu has gone from prey to predator and awaits Tatsu under a bridge:

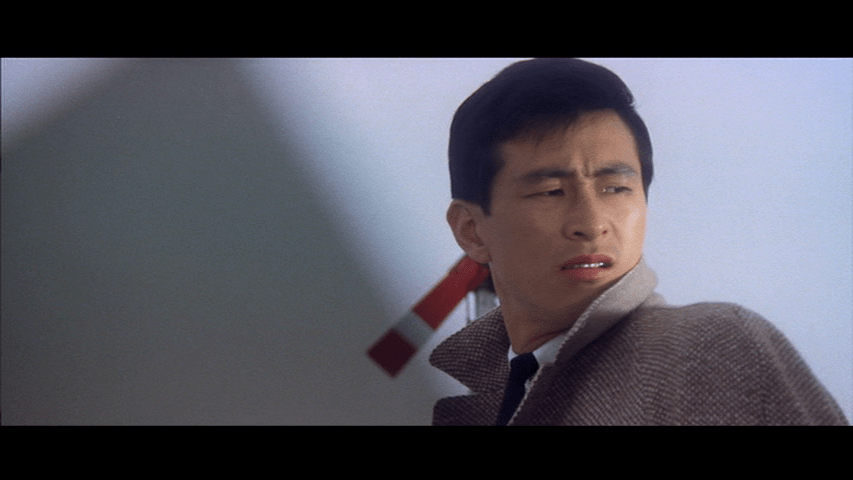

There’s a close-up of Tatsu standing in front of a railway signal:

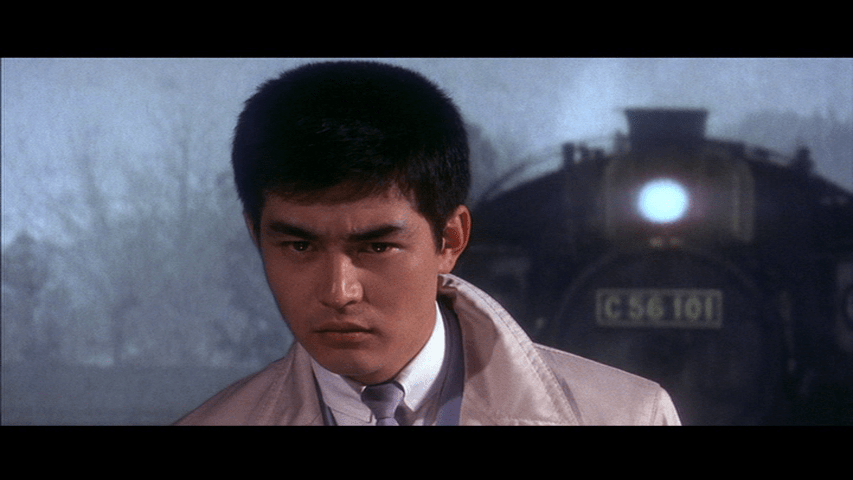

Followed by one of a train:

And suddenly the Viper is aiming his gun at the Phoenix:

In quick succession there’s a close-up of Tatsu, followed by one of Tetsu, followed by a shot of a steam engine’s boiler:

Still Tatsu waits:

As the train continues to draw closer to Tetsu, Suzuki switches to wonderfully artificial-looking back projection:

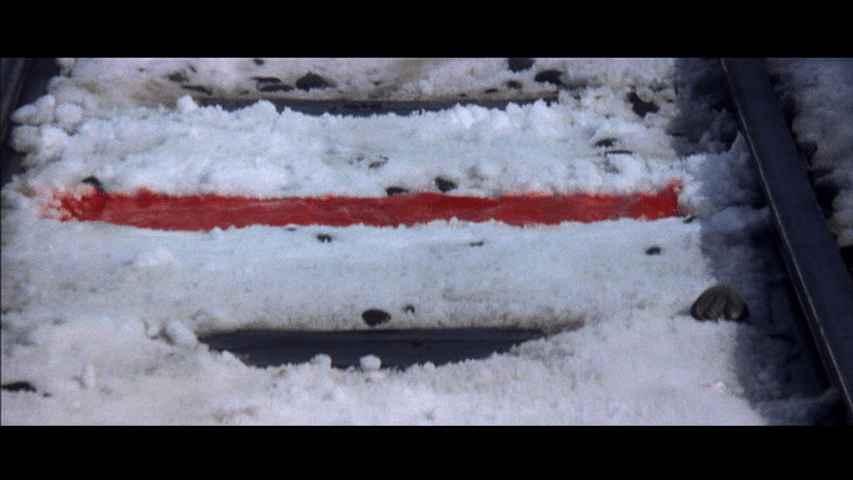

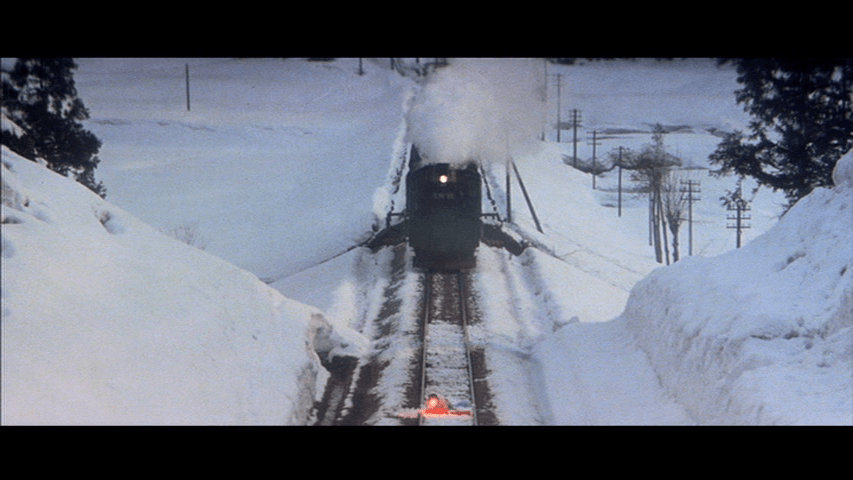

Cut to a POV shot from Tetsu’s perspective as he counts railway ties: “15 yards, 14, 13, 12 . . . 10.” The end of the list is marked by a red line in the snow defining what we learned earlier is the limit of his range:

As Tetsu makes his move, Tatsu finally starts to fire:

Tetsu runs toward him and dives to the ground, shooting back:

Cut first to close-up of the train, then to a long shot of Tetsu walking away, apparently having won:

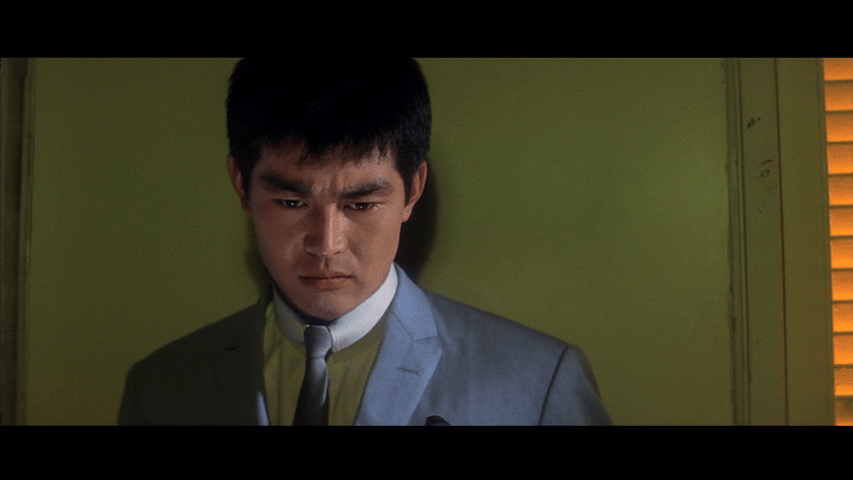

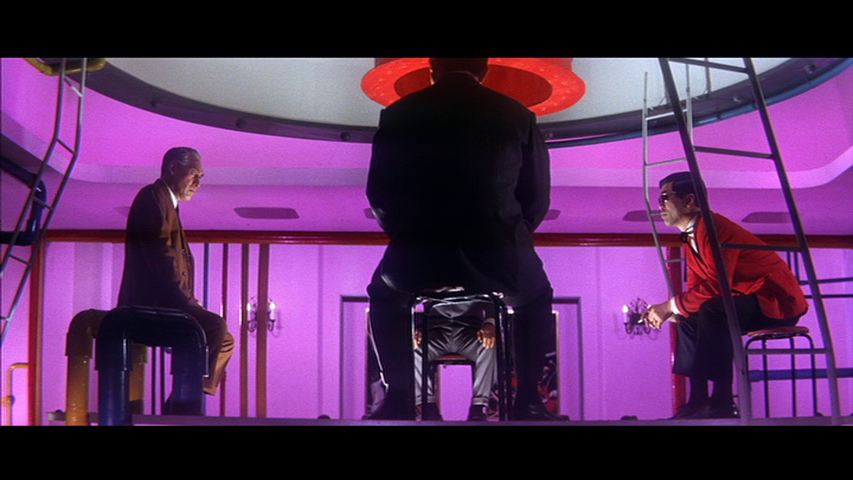

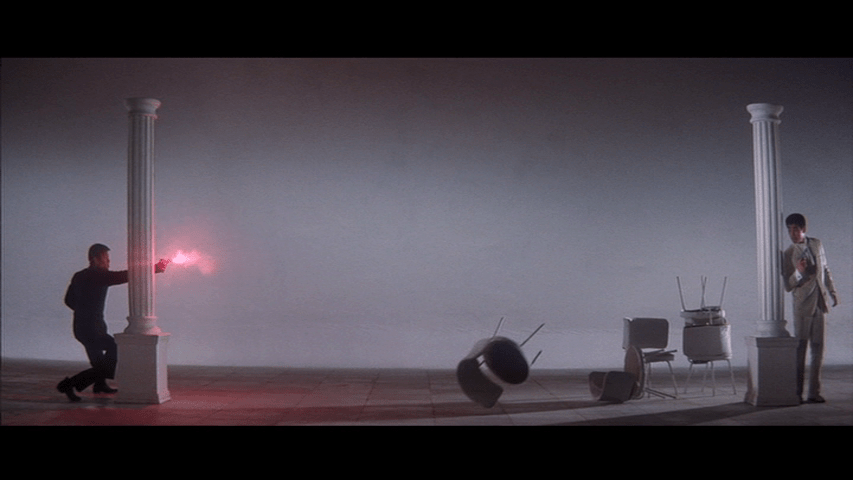

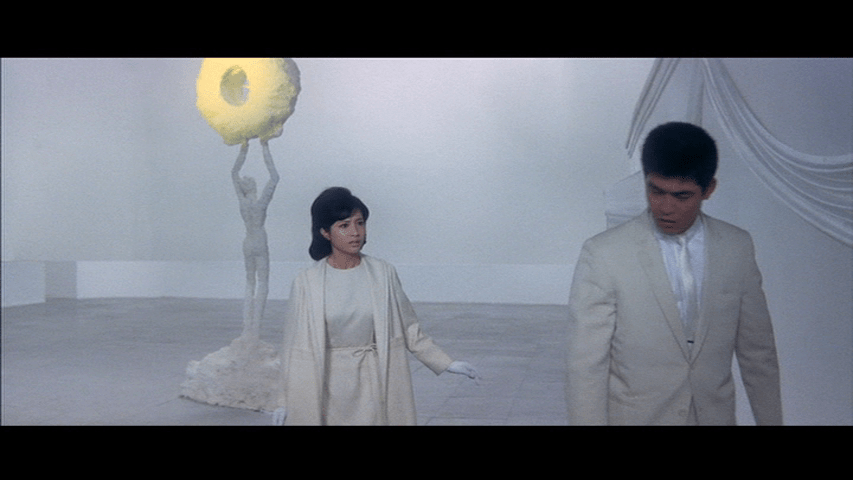

Yacavone writes that this all “plays like deliberately orchestrated nonsense,” but also concedes that it’s “exciting on its own terms,” which I think is basically the same thing Rayns is saying and goes double for Tokyo Drifter‘s highly-stylized climactic shootout. It follows Kurata betraying Tetsu in the scene that most directly inspired this month’s drink photo:

And features the latter first taking cover behind a slim column:

Then throwing his gun into the air, catching it, and shooting the man who sold him out in one smooth motion:

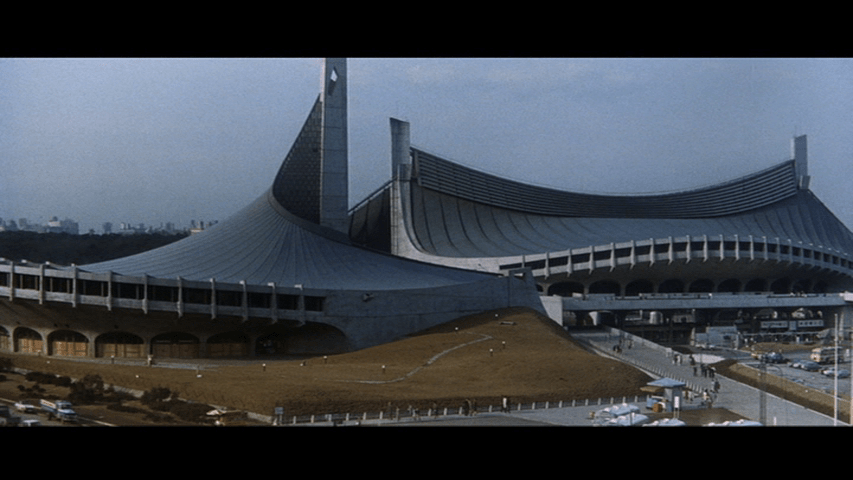

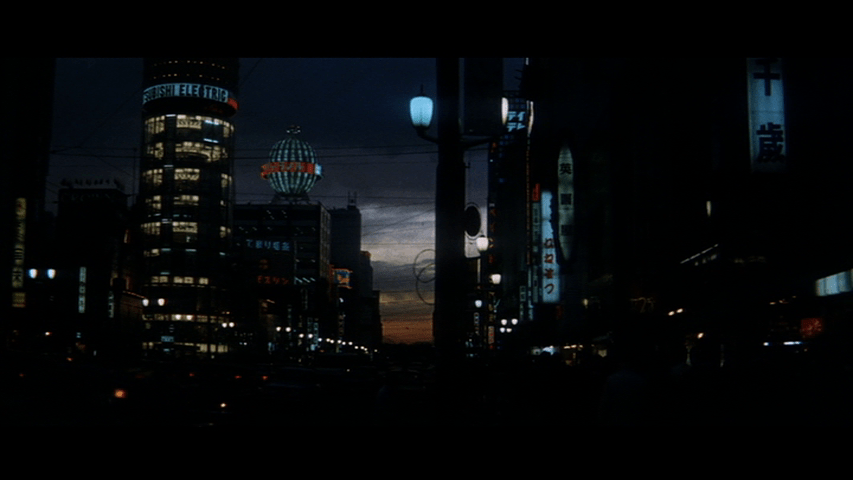

I appreciate Yacavone’s writing on this film because he draws attention to details I suspect I might have missed otherwise, such as the absence of any “visual trace of prewar central Tokyo” from the title sequence featuring a montage of tourist attractions built in preparation for the 1964 Summer Olympics:

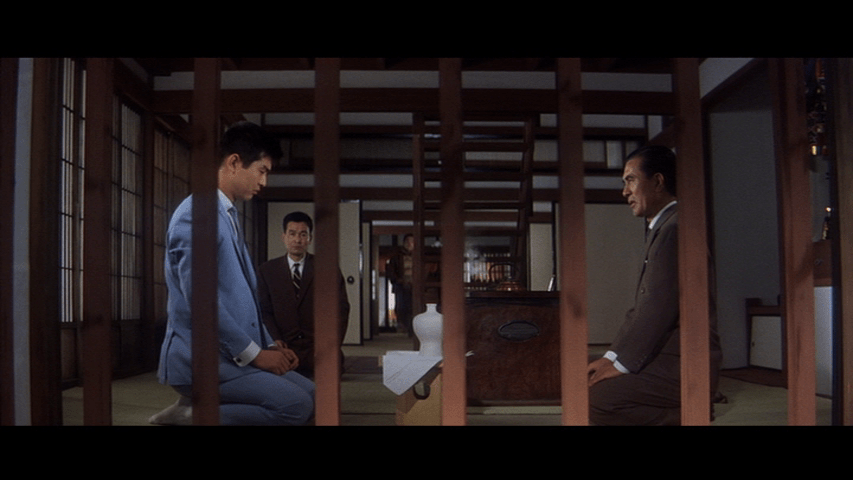

The way it “exploits the recessed paneling of Tokugawa architecture to suggest an infinite depth that is equated with tradition” and “suggest that in its own way Yamagata, reminiscent of an age of duty, aristocracy, and self-sacrifice, is just as deathly and alienating as Tokyo”:

Or even just the simple fact that Hideaki Nitani’s character Shooting Star has the same initials as Suzuki.

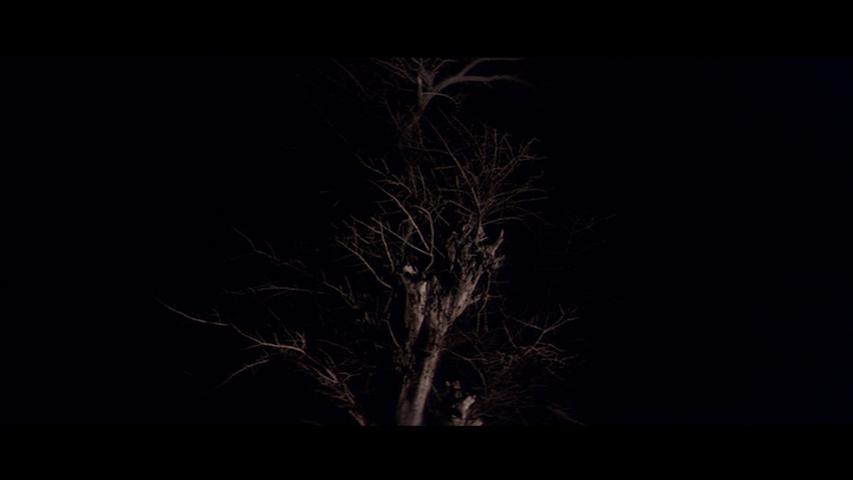

But the overall contours of Tetsu’s journey are easily discernible even to the uninitiated through universal devices like a low-angle shot of a tree in front of a darkening sky that charts his withering loyalty to Kurata:

And when the final showdown ends with Tetsu rejecting the woman who loves him (Chieko Matsubara) on the grounds that he “can’t walk with a woman at [his] side” and exiting through a vaginal hallway, we understand that he has been reborn into the world as a truly independent Tokyo drifter:

Which strikes me as representing a level of meta complexity worthy of Pavement’s immortal lyrics “you’ve been chosen as an extra in the movie adaptation of the sequel to your life.”

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.