After writing about the Tour de France, blackcap bush in my backyard, and 2024 Paris Olympics in my first three July Drink & a Movie posts, I had two obvious places to look for inspiration for my last one. Rather than choose between the birthday celebrations of the two countries members of our household have citizenship in, though, I decided to leverage my penultimate “bonus” post (my goal is 54 in four years, so just one per month won’t quite cut it) to do both. It’s arriving a bit later than intended, but my follow-up to my Canada Day commemoration featuring Crimes of the Future therefore highlights what I think surely must be the greatest “3rd of July” film ever made, Lonesome. Here’s a picture of my Criterion Collection DVD copy:

As a film in the public domain, you can also easily find it streaming for free on platforms like Tubi. The beverage I’m pairing with it is the Sherry Tale Ending that Toronto-based bartender Colie Ehrenworth created for the fourth Canadian season of the Speed Rack bartending competition, which is included in the book A Quick Drink by its founders Lynnette Marrero and Ivy Mix. Here’s how to make it:

1 1/2 ozs. Reposado tequila (Espolòn)

3/4 oz. Amontillado sherry (Lustau)

1/2 oz. Lillet Blanc

1/4 oz. Maple-sugar syrup

3 dashes Angostura bitters

Make the maple-sugar syrup by combining equal parts by volume of maple syrup, turbinado sugar, and water in a small saucepan and stir over low heat until the sugar has fully dissolved. Remove from heat and cool completely. To make the cocktail, stir all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled cocktail glass.

Normally I try to avoid repeating base spirits in consecutive months, but that actually doesn’t seem so inappropriate in an extra post arriving hot on the heels of its predecessor–think of it as a sort of “two for one” deal! I like the Canada connection for the same reason, which: Ehrenworth advises using maple syrup from Ontario and that definitely is the way to go, especially if like us you’re lucky enough to have family who make their own and are willing to share. This drink was specifically engineered to be a lower ABV nightcap by combining elements of the Adonis, a sherry-based classic cocktail, and a 50/50 Manhattan and yet another affinity between this month’s concoction and its predecessor is that the tequila is once again a supporting player. The dominant flavors here are instead dried fruit notes from the amontillado on the sip which gracefully give way to the candied citrus from the Lillet on the swallow. So it’s a sweet drink, yes, but an agave and dark molasses finish prevents it from ever coming across as cloying, making the Sherry Tale Ending a light but satisfyingly complex way to finish your night.

At just 69 minutes, Lonesome would also be a great way to unwind after an evening out. The plot is simple: lonely hearts Jim (Glenn Tryon) and Mary (Barbara Kent) arrive home to their respective empty apartments after a half-day at work feeling listless:

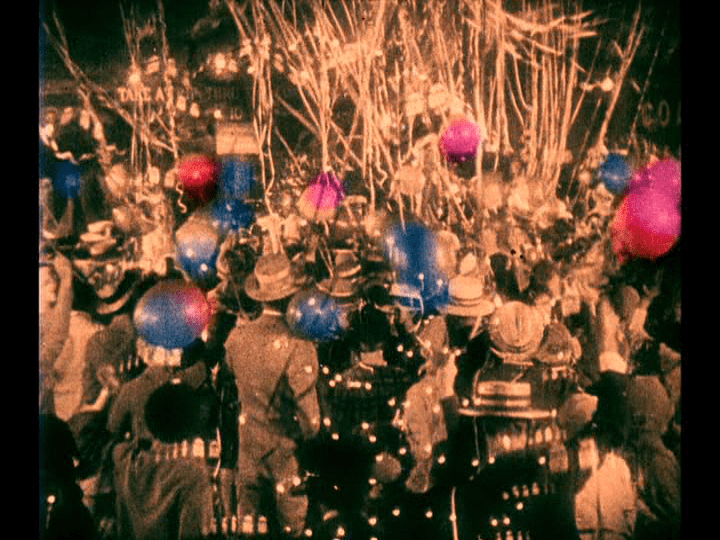

Suddenly, each hears this bandwagon as it passes by on the street below:

Lured by its siren song, both decide to head to Coney Island beach. Jim spies her on the bus ride there fending off a would-be Romeo with the implicit threat of brooch pin violence

Impressed, he pursues her through the crowd upon arrival:

Undeterred by either a young hooligan who trips him:

Or her apparent disinterest in watching him perform feats of strength:

And with a bit of extra prompting from an auspicious fortune that reads “you’re about to meet your heart’s desire”:

He finally succeeds in catching her eye in a very nice rack-focus shot:

And before long they’re talking to each other on the beach:

Literally: while its first 29 minutes are silent (although they do feature a sophisticated sound mix timed to the action), Lonesome contains three dialogue sequences which most critics revile, but that Aaron Cutler argued in a blog post for Moving Image Source “add to the rest of the film largely because they are inconsistent with it.” Referring also to the final one, he continues:

For the first time in their lives onscreen, Jim and Mary speak, and they do it because of each other. When Jim promises Mary that “We’ll never be lonesome anymore,” he says it in his own voice, out loud; when he later argues with a judge and police, he does so with the voice that Mary helped him find. Even after the lovers fall back into silence, we retain the sounds of their voices in our heads, distinguishing them as individuals.

To Cutler the “brightly smeared” colors that suddenly make an appearance in the film’s 37th minute perform a similar function.

“Within a long-shot world,” he says, “Jim and Mary see each other in medium and close-up; within a black-and-white, silent world, they can see and hear each other in color and in sound.” Anyway, Jim and Mary have lots of fun together on the boardwalk after the sun goes down:

And he wins her a doll:

But the party ends during a ride on the dual-track Jackrabbit Racer roller coaster when a wheel on Mary’s car catches fire:

She faints:

And when Jim tries to come to her aid, he is arrested by a bizarrely aggressive cop, leading to the scene described by Cutler above in which his obvious passion earns him a reprieve:

Alas, he and Mary are unable to locate each other again in the throng:

A squall suddenly blows up while they’re searching and, not having exchanged contact information, they return home despondent and alone. But wait! Jim puts on a record of the song he and Mary danced to earlier; in the next shot, she hears it coming through the walls and pounds on them, yelling for her neighbor to turn it off:

Jim recognizes Mary’s voice and rushes down the hall:

They’ve been living next to each other all along! As they embrace, the lovers contemplate Mary’s doll, which as Glenn Erickson noted in a Blu-ray review has had “its face half washed away in ‘tears'” by the storm, thus becoming a “physical ‘locator'” for the heartbreak they have just triumphed over:

The end. Lonesome is brilliantly, restless inventive from start to finish and probably contains twice its running time’s worth of visual information if you count the many superimpositions, such as the clock face which accompanies shots of Jim and Mary at work and portraits of the people she is connecting to one another in her job as a switchboard operator:

As Richard Koszarski observes in his excellent DVD commentary track, even director Pál Fejös’s most ostentatious images are far more innovative than they appear:

When a shot of Mary at work seems to elbow a shot of Jim right out of the frame, we are seeing this new optical printing technology at work. The effect is not, as some historians have said, a panning shot in which the camera moves to the left or right, but a much more complicated technical exercise introduced to Hollywood only a few months before Fejös shot this film in which the optical printer and a new Kodak duplicating film stock could allow filmmakers the sort of flexibility in shaping the image that prefigures the development of digital cinema decades later.

Meanwhile, for the ostensibly more straightforward scenes that begin the film, cinematographer Gilbert Warrenton “developed a small mobile camera system that allowed him to follow the actors very closely as they moved within the cramped confines of their cold water flats”:

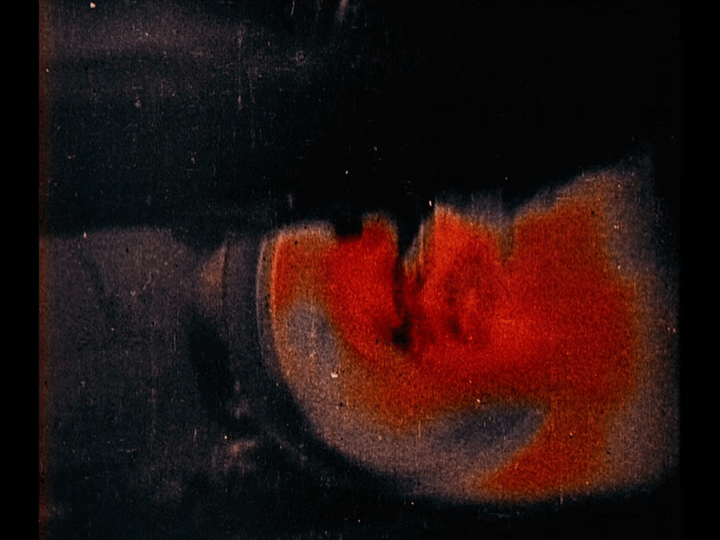

Fejös and company also make great use of a technique which was falling out of style with the advent of sound in the applied color sequences, which as Joshua Yumibe explains in his chapter for the book Color and the Moving Image were “proving difficult to apply in ways that did not interfere with soundtracks on prints.” Universal nonetheless approved their use here both to facilitate marketing the film in the company’s publicity journal Universal Weekly as “the first talking picture with color sequences” and because they “greatly enhance an already beautiful story.” Specifically, per Yumibe, color formally reinforces the narrative ambivalence he (riffing on Siegfried Kracauer) reads into Lonesome‘s insistence on tearing Jim and Mary apart before it allows them to be together by using “the same hues that previously colored their romance” for the flames that result in their separation.

A sequence in which Jim and Mary search for a lost ring on the beach serves a similar function. Sure, they are ultimately successful:

But what were the chances? As Jonathan Rosenbaum said about my February, 2024 Drink & a Movie selection The Young Girls of Rochefort, despite the fact that all eventually ends well, “the missed connections preceding this resolution are relentless, and one may still wind up with a feeling of hopeless despair despite the overdetermined happy ending.” No wonder, then, that he numbers both that film and Lonesome among his hundred favorite films!

One of the best things about Koszarski’s commentary are when he points out places where, with his assistance, things obviously seem to be missing like a “gag title” to explain Jim’s exchange with the man who serves him coffee and doughnuts on his way to work:

Flaws like this are on of the reasons that David Cairns, another champion of Lonesome‘s dialogue scenes, provides for calling it “a magnificent one-off” in a 2016 blog post: “I wish the part-soundie era had lasted another five years. When the two leads abruptly start speaking to each other in live sound on the beach at Coney Island, the jarring transition from one medium to another is beautiful. You can’t get that in a perfect film, only in a makeshift masterpiece like this one, a superproduction assembled on shifting sands.” Talking about this moment:

He concludes by saying, “When the film reaches its tearful conclusion, sudden nitrate decomposition afflicts the footage, with PERFECT artistic timing — it drives home the fragility of what we’ve been watching.” It may be a bit of a stretch, but this strikes me as a possible callback to the delicate balance of the Sherry Tale Ending and even the holiday that occasioned this post. It’s great that the United States has made it to 249, but if we’re not careful it won’t still be around next year to mark its Semiquincentennial, let alone make it all the way to the year 2074.

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.