You’d never know it from this monthly series, but My Loving Wife and I aren’t drinking as much as we used to, and the most common way I discover new cocktails these days is by trying to find novel uses for old bottles which have been languishing in our liquor cabinet and refrigerator for far too long. And so it was that I found myself mixing up The Navigator which Frederic Yarm featured on his blog in 2018 earlier this year with some of the madeira I purchase each December to make bigos, a nod to both my upbringing in Pennsylvania Dutch country where we eat pork and sauerkraut on New Year’s day for good luck and the two years of Polish I took in college. When it proved to be a perfect platform for not just that spirit, but two other household favorites, Bacardí Reserva Ocho and Rothman & Winter’s Orchard Apricot Liqueur, I immediately decided to feature it in one of my last remaining Drink & a Movie posts. Here’s how to make it:

1 oz. Bacardí Reserva Ocho

1 oz. Rainwater Madeira (Leacock’s)

3/4 oz. Lemon juice

1/2 oz. Simple syrup

1/4 oz. Apricot liqueur (Rothman & Winter)

Combine all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with an edible orchid and a lemon twist.

Punch provided a great overview of rainwater Madeira in 2017 for their “Bringing It Back Bar” series. Once considered the most prestigious style in the category in United States, it emerged from Prohibition with a debased reputation but has recently found favor with bartenders who find it “attractive not only for its relatively low price point, but for its subtlety.” It functions in The Navigator the same way as it does in the recipes linked to in that article–as a medium-dry counterpoint to the apricot liqueur and rum, resulting in an easy-drinking concoction which is sweet, but subtle instead of cloying. That’s actually not a terrible way to describe the movie I’m pairing it with, The Strange Case of Angelica, which like Madeira and The Navigator’s presumptive namesake Prince Henry hails from Portugal. Here’s a picture of my Cinema Guild DVD copy:

It’s also available for rental or purchase on Apple TV+, and some people (including current Cornell University faculty, staff, and students) may have access to it through Kanopy via a license paid for by their local academic or public library as well.

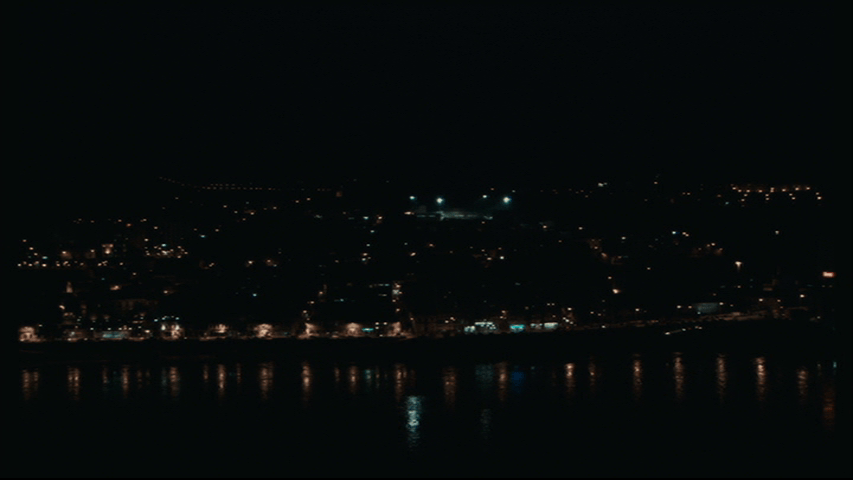

Director Manoel de Oliveira was 101 years old and had 30 features under his belt when The Strange Case of Angelica debuted at Cannes in 2010, and it has a stately mien and pacing befitting such a remarkable resume. The film begins with an epigraph by Antero de Quental: “yonder, lily of celestial valleys, your end shall be their beginning, our loves ne’er more to perish.” This is followed by two languorous minutes of titles accompanied by Portuguese pianist Maria João Pires performing the third movement of Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 3 in Bi Minor which unspool over a nighttime cityscape of Régua from a vantage point across the Douro River:

The action begins with a 3:30 single take street scene also shot with a stationary camera and featuring a “strongly diagonal” (per James Quandt on the DVD commentary track) composition that will accrete significance as the movie progresses. A man inquires as to the whereabouts of the photographer who lives above the shop is car has stopped in front of:

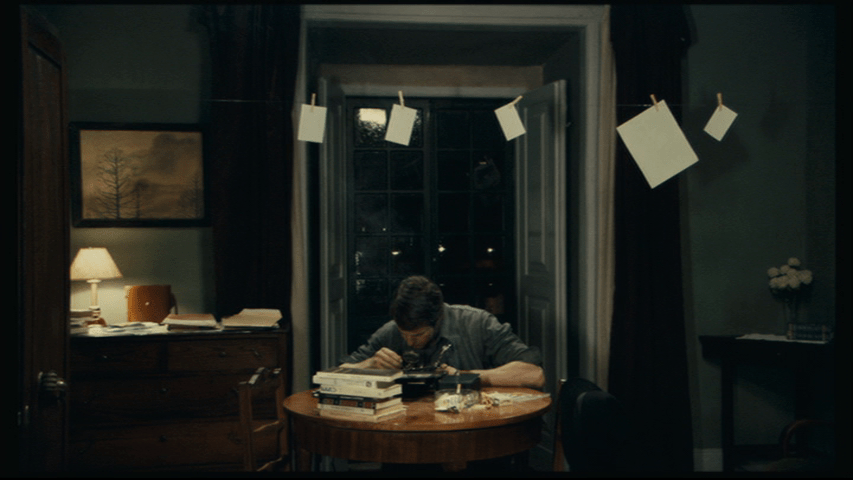

And is told that he’s out of town, but a passerby helpfully offers directions to the home of a young “Sephardi emigrant” he knows who “takes photos all over the place.” This turns out to be Isaac (Oliveira’s grandson Ricardo Trêpa), who we meet bent over a malfunctioning wireless in what J. Hoberman identifies as a reference to Jean Cocteau’s Orphée in an essay collected in his book Film After Film:

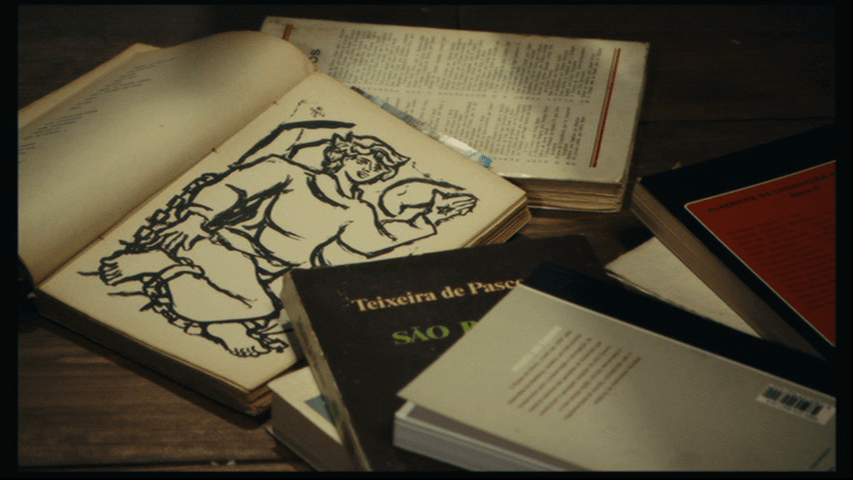

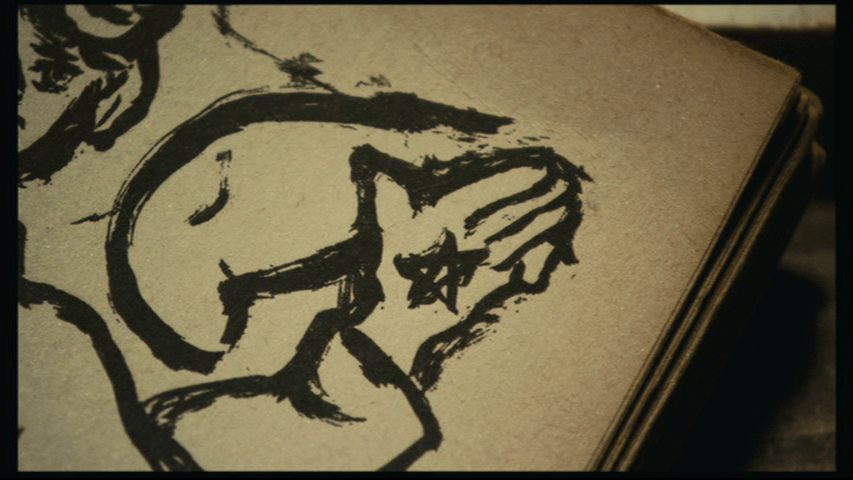

Unable to make the “static-garbled radio transmissions” any clearer, Isaac shoves the device forward in frustration, knocking a pile of books onto the floor. When one volume falls open to this page:

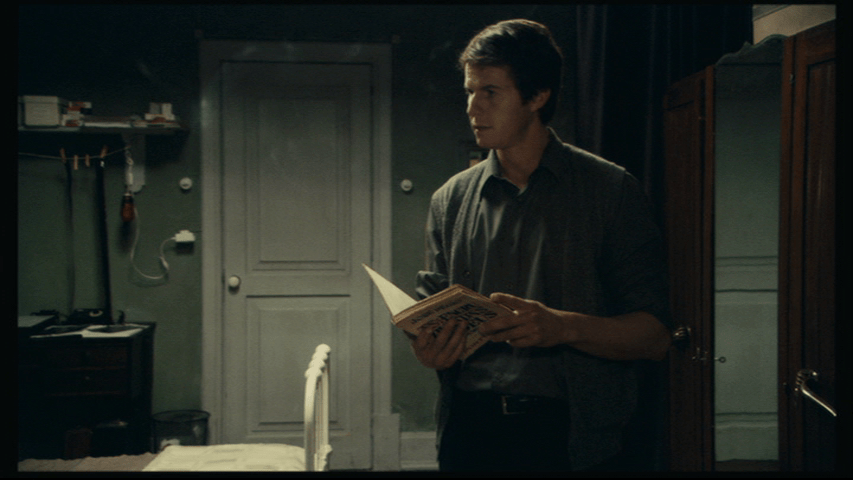

He picks it up and begins to read. “Dance! O stars, that in constant dizzying heights you follow unchanging. Exalt, and escape for an instant the path that you are chained to.” Suddenly, there’s a knock at the door.

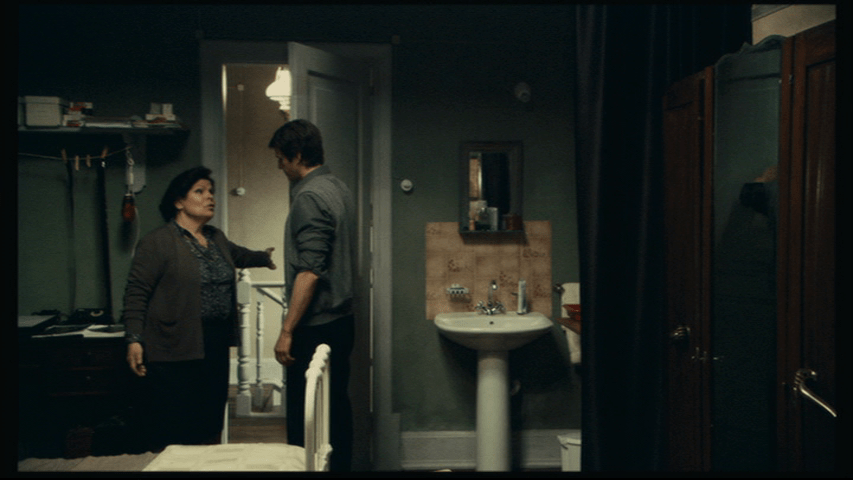

“It’s the angel!” Isaac exclaims and returns to the book. “Time, stand still, and you, former beings, who roam fantastical, celestial ways. Angels, open the gates of heaven, for in my night is day, and in me is God.” As he finishes the passage, there’s another knock, now accompanied by a voice calling his name. Shaken at last from his reverie, Isaac puts the book down and answers the door to find that it’s his landlady Madam Justina (Adelaide Teixeira), who Quandt describes as “like a kind of one-woman Greek chorus,” bearing a message that he has been summoned by a “very important lady” to take pictures of her daughter.

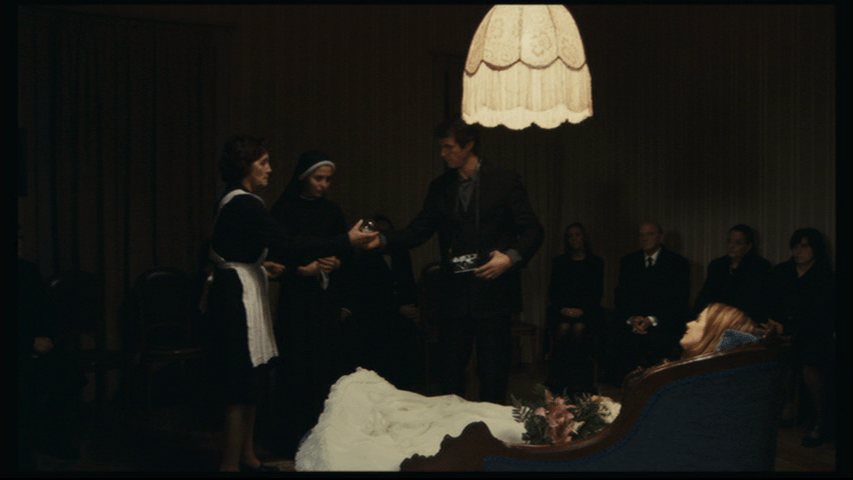

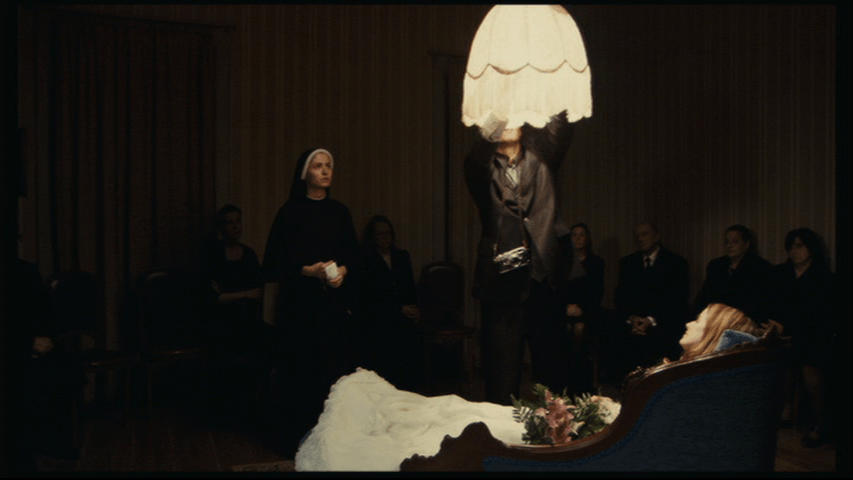

Upon arrival Isaac is greeted outside at the foot of a staircase by a nun (Sara Carinhas) who turns out to be the sister of the woman he is there to photograph (Pilar López de Ayala) and her maid (Isabel Ruth).

They inform him that his subject Angelica has just passed and that his commission is to create “one last souvenir, even if it is very sad” at the behest of her mother. Isaac asks for a stronger bulb for the room’s only light, which Hajnal Király characterizes as “a historical memento of the Oliveira family, owners, at the beginning of the twentieth century, of a factory manufacturing electric devices” in her book The Cinema of Manoel De Oliveira:

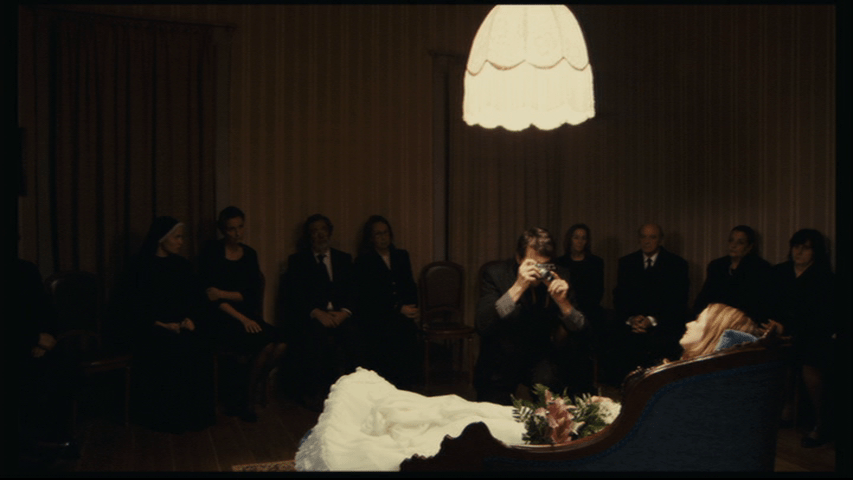

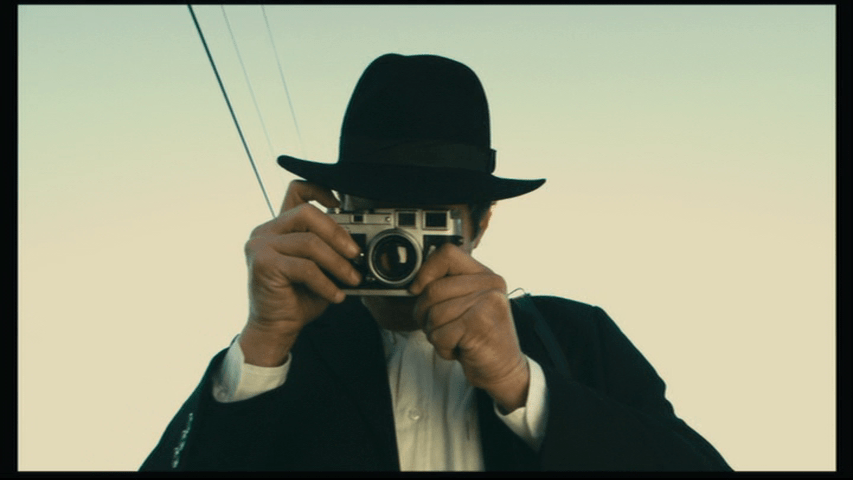

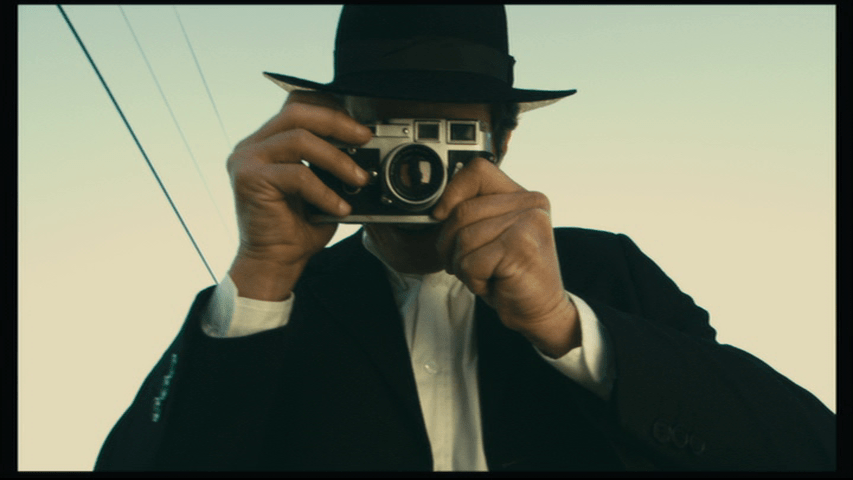

Then sets to work in a photo shoot depicted through a combination of long shots of Isaac:

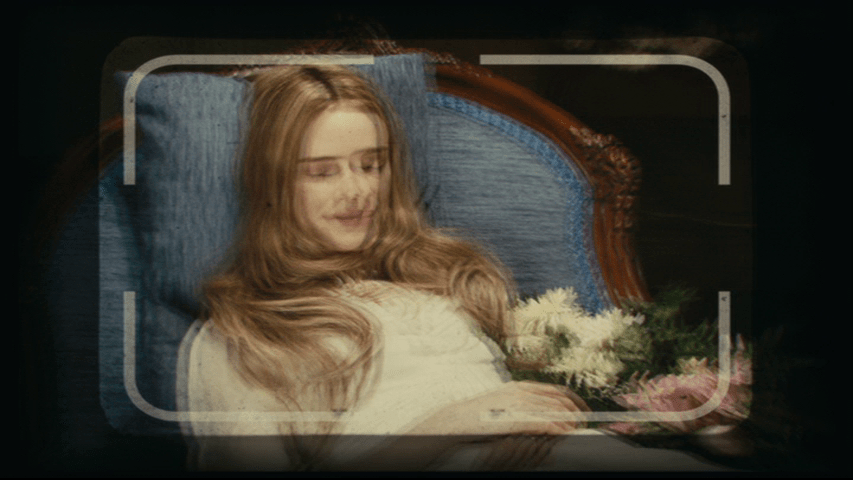

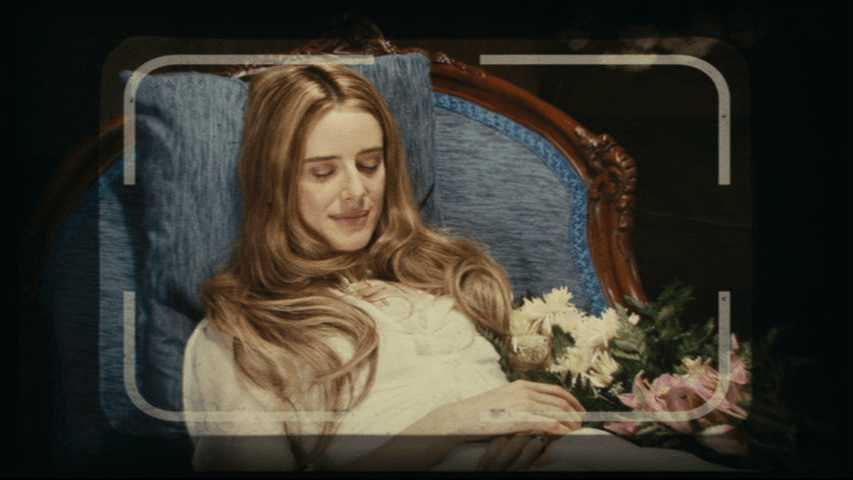

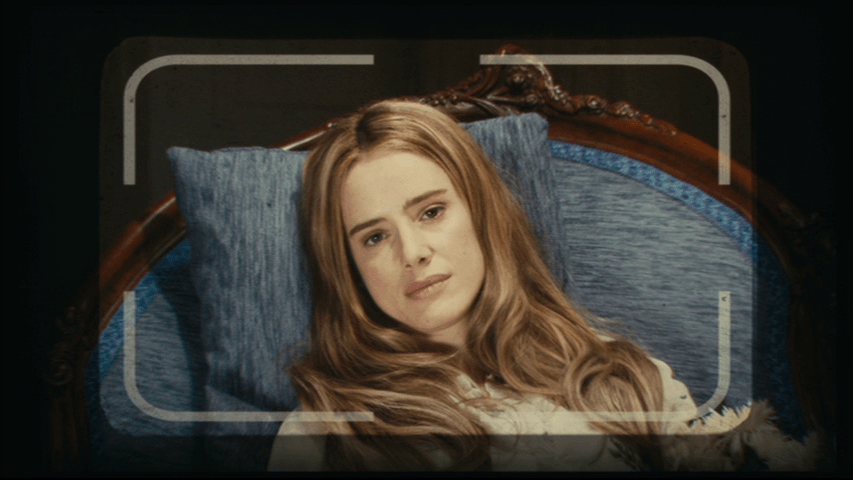

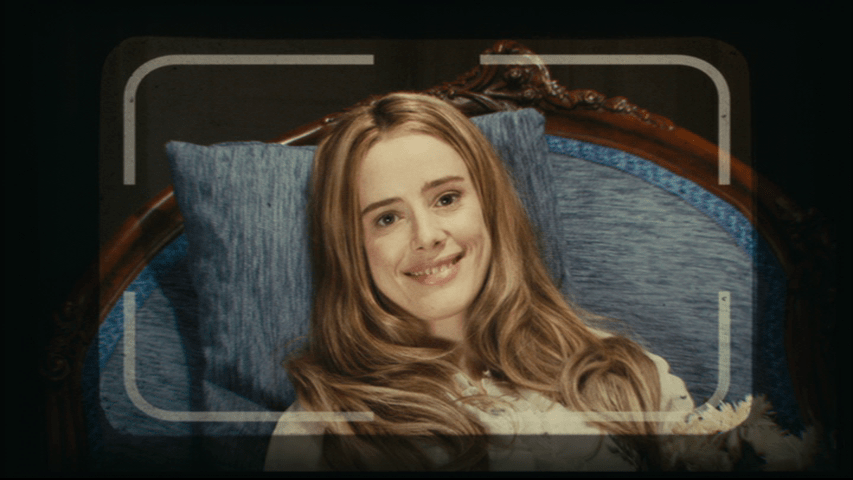

And point-of-view shots complete with frame lines showing us exactly what he’s looking at as he focuses his camera:

He moves in for a close-up:

When suddenly Angelica appears to open her eyes and smile at him:

He is obviously shocked:

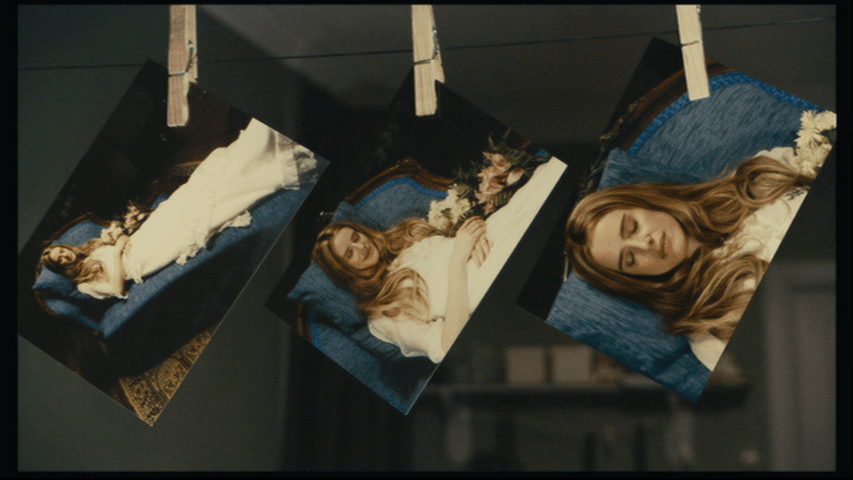

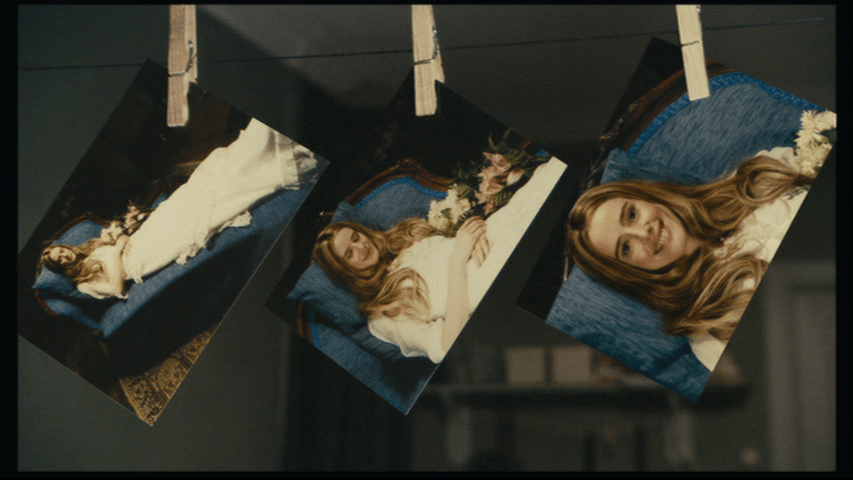

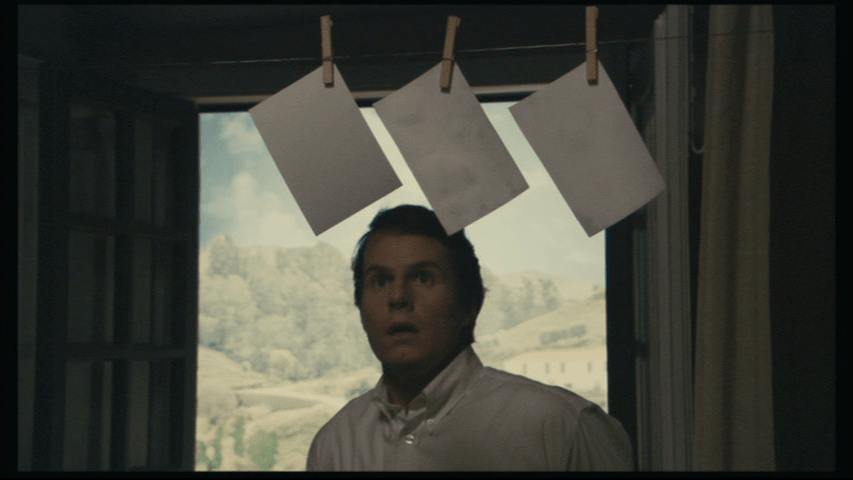

But upon realizing that no one else has noticed anything strange hastily finishes up and departs. The next day as he’s developing the pictures he took, an image of Angelica again comes to life, causing him to once more jump back in surprise:

Moments later he spies some laborers tilling the soil in a vineyard across the river:

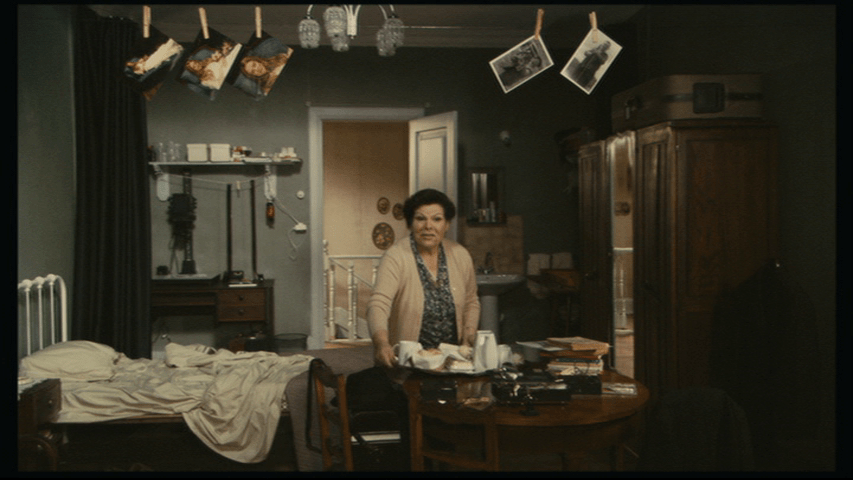

And resolves the photograph them, much to the chagrin of Madam Justina, who laments the fact that “hardly anyone works like that these days”:

As Quandt notes, “Oliveira’s materialist appreciation of sound is wonderfully apparent” in the sequence that follows, which features more slanted lines:

And a charming call-and-response working song about a shabby suit of clothes. It ends with Isaac appearing to hear bells calling mourners to Angelica’s funeral, for he next appears in the church where one of the friends gathered around her coffin comments that “she looks like an angel from heaven”:

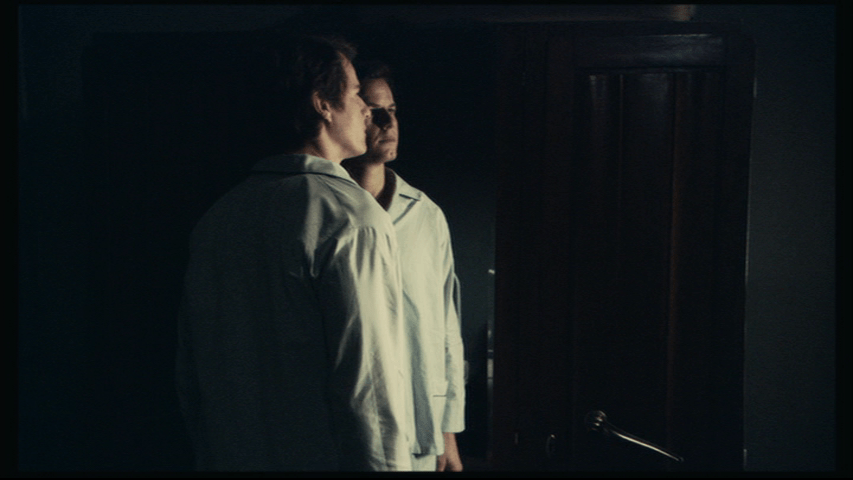

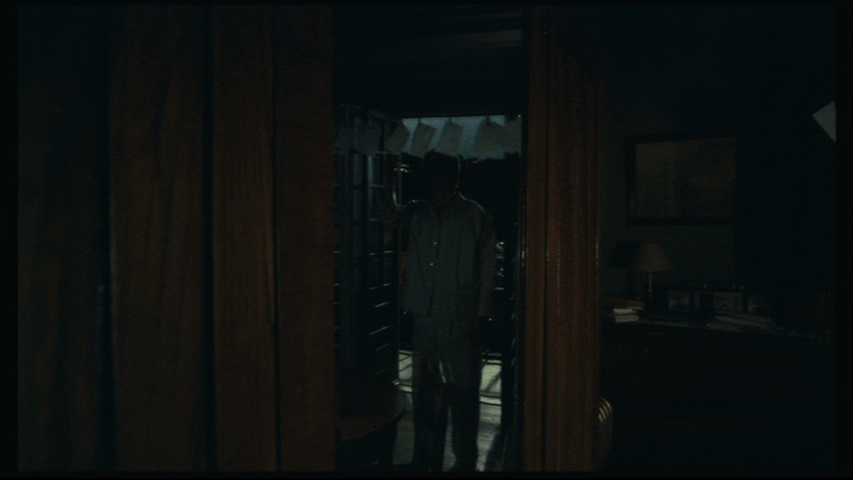

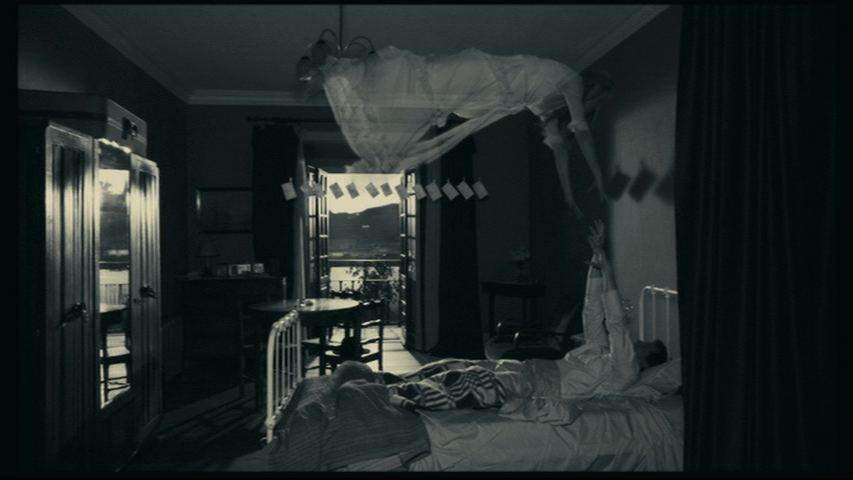

Which inspires him to recite the snippet of poetry he read earlier. That night in a scene which begins with what we soon realize is a shot of his reflection in a mirror, Isaac wakes up and walks over the photos hanging on a line in front of his balcony:

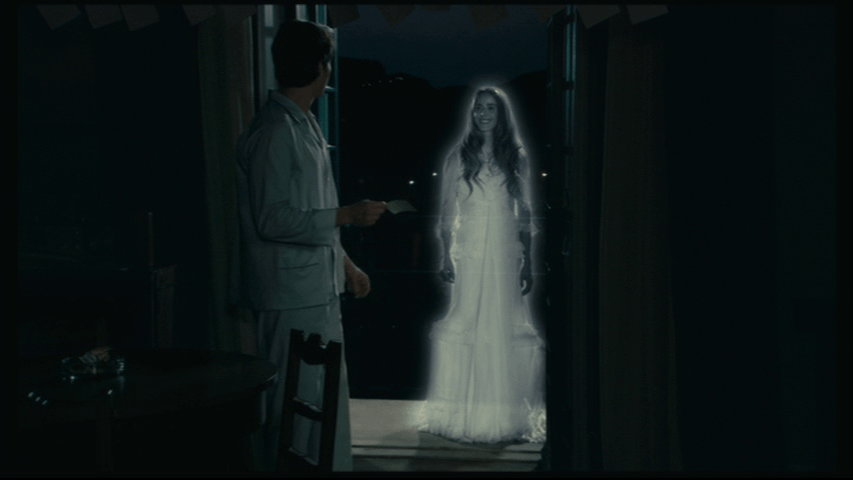

As he stands there an apparition materializes behind him:

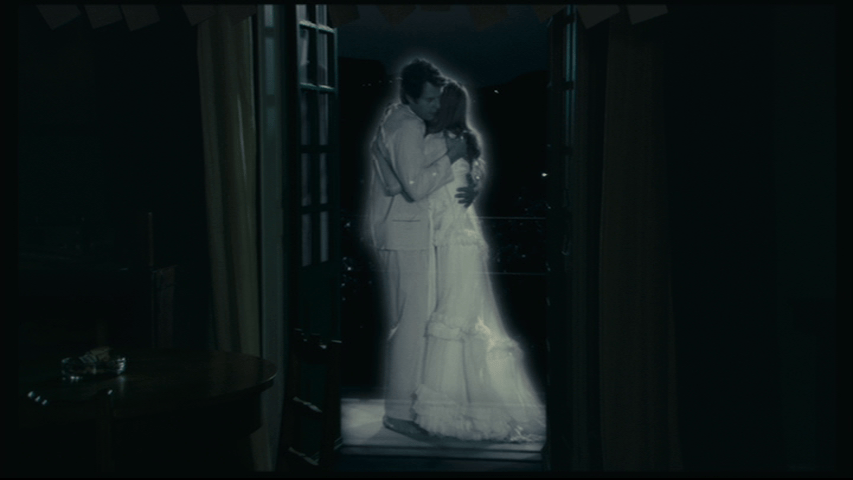

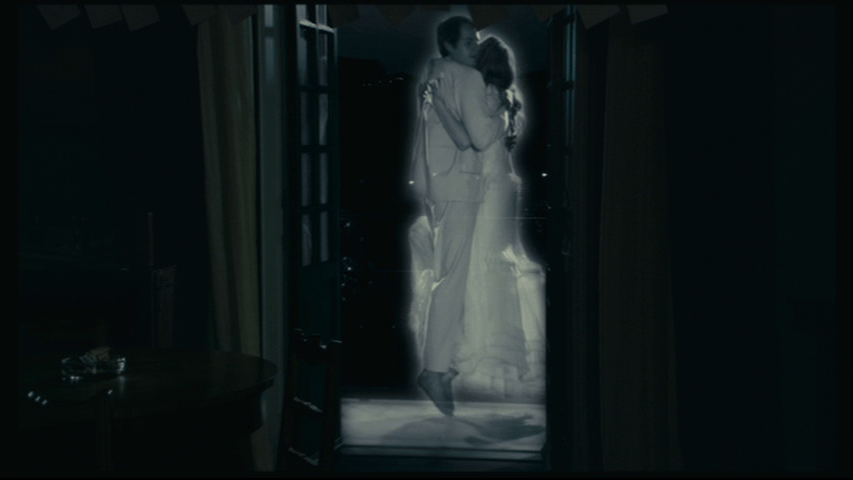

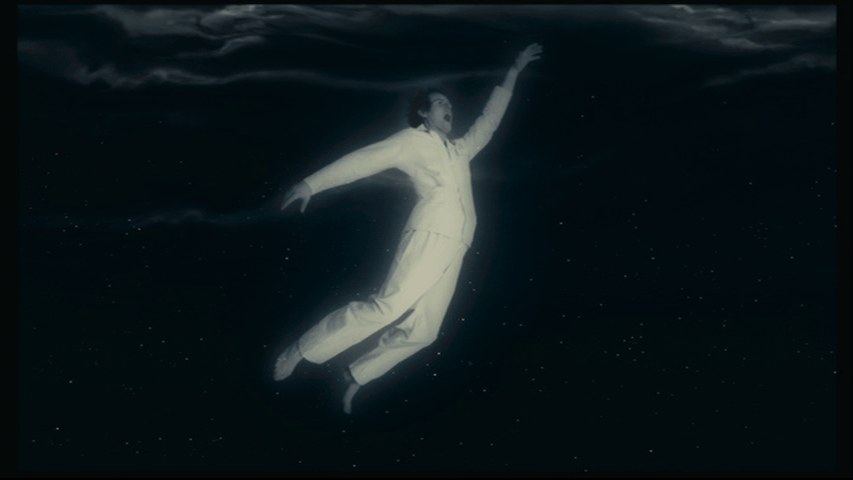

He passes through the doorway and becomes translucent himself. The two of them embrace and rise into the sky:

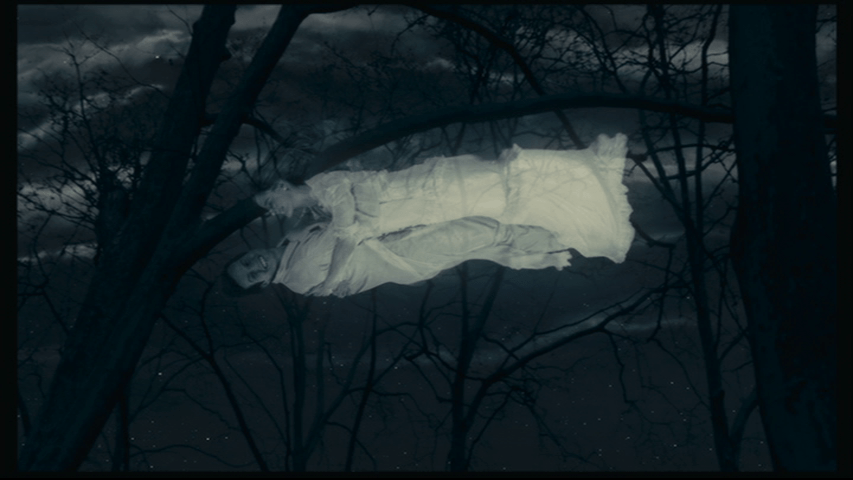

Leading forthwith to my favorite image from this movie, the epically goofy grin plastered on Isaac’s face as he floats supine through the air:

Which he wears right up until the moment when a strikingly topographical overhead shot of the Douro abruptly gives way to one of him in freefall:

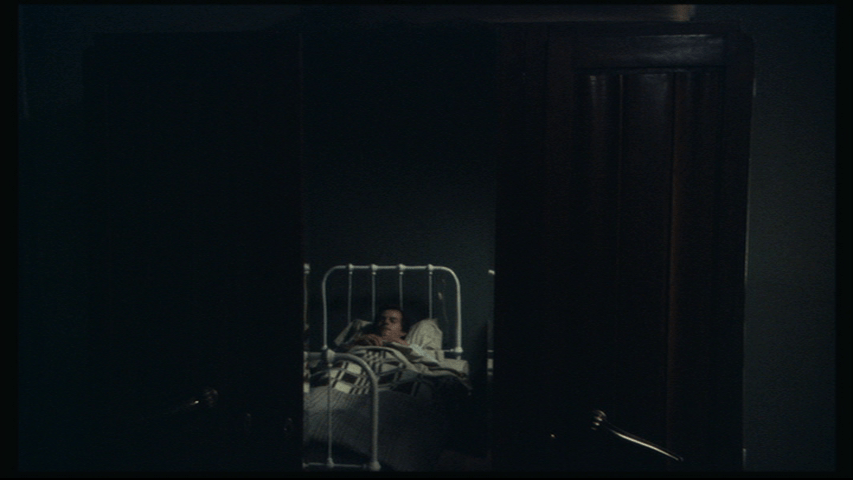

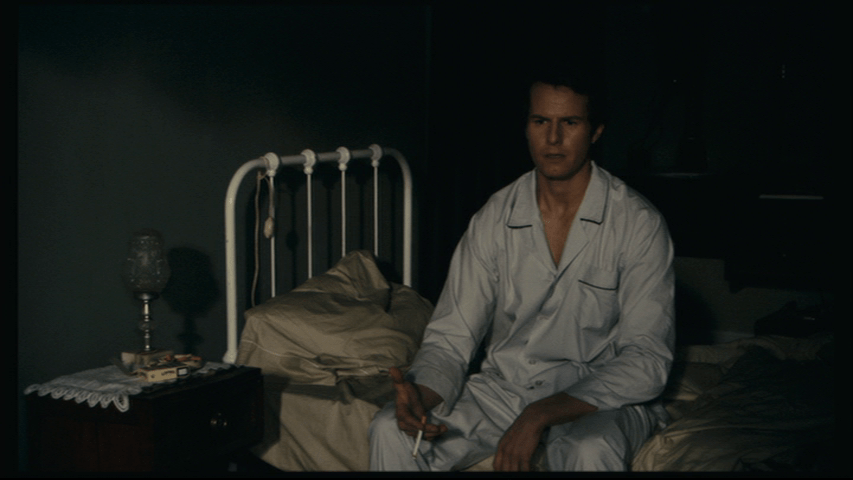

He awakens the next morning with a start and lights a cigarette:

“That strange reality . . . perhaps it was just a hallucination? But it was just as real as this. Could I have been to that place of absolute love I’ve heard about?” Then: “I must be out of my mind.” The second half of the film chronicles his self-deportation from the land of the living, which Daniel Kasman read as reminiscent of the director of my September, 2024 Drink & a Movie selection History is Made at Night in a dispatch filed from Cannes 2010: “as in Borzage, escape from the world’s ails to the bliss of an otherworldly love is at once the most cowardly and most heroic of actions.” As part of The Strange Case of Angelica‘s very first wave of viewers, Kasman understandably focuses specifically on the titular character’s role in precipitating Isaac’s withdrawal from his fellow lodgers:

Growing frustration when Angelica remains tantalizingly out of reach even in his dreams::

And increasingly public erratic behavior:

But as Rita Benis notes in a paper collected in the book Fearful Symmetries called “The Abysses of Passion in Manoel de Oliveira’s The Strange Case of Angelica,” the film’s fantastical elements like Isaac’s visions of Angelica are strongly linked to its realist sequences like his efforts to document the “old-fashioned” ways of the vineyard workers visible from his apartment and “their contrast is what generates the real fear implicit in the film,” such as in “the distressing sequence where he desperately follows a tractor working the rocky soil, taking furious snapshots to the fading traces of an ancient world (the connection between man and earth)”:

These shots are, of course, immediately followed by one of him thrashing around in his bed, haunted by the sounds of hoes striking the earth over and over again, and they finally unlock the secret to all those diagonals: each of Isaac’s impossible loves are a step on what is ultimately one long stairway to heaven.

J. Hoberman closes his essay on The Strange Case of Angelica with a quote:

The last living filmmaker born during the age of the nickelodeon, Oliveira told an interviewer that cinema today is “the same as it was for Lumiére, for Méliès and Max Linder. There you have realism, the fantastic, and the comic. There’s nothing more to add to that, absolutely nothing.” The great beauty of this love song to the medium is that Oliveira’s eschewal remains absolute. It’s a strange case–pictures move and time stands still.

The other night at dinner we went around the table at the request of my children and all said what we’d eat if we had to subsist on just one food for the rest of our lives. Neither Oliveira’s film nor The Navigator may be the most daringly innovative creation featured in this series, but they both contain everything I’m looking for in a drink and a movie respectively, and while it would be suboptimal (to say the least) to be confined to such a limited diet, I can think of far worse answers to the cinema and cocktail versions of my kids’ question!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.