I knew right from the start that this series would eventually feature the Cinema Highball, an ingenious rum and Coke variation created by Don Lee and included in The PDT Cocktail Book, but what to pair it with? A name like that suggests primacy of place–should I save it for the final entry and write about it alongside my favorite movie, I wondered? But then I’d have to pick a single favorite, and as the days went by my options narrowed. The Flowers of St. Francis and Early Summer came off the board within six months of this project beginning and The Passion of Joan of Arc and Pyaasa followed in its second year of existence. Meanwhile, another question was beginning to vex me: which of the 100+ films directed by Jean-Luc Godard was I going to tackle? The solution to both my problems arrived simultaneously last May when I realized I wouldn’t finish my post about Stalker before the first of the month, eliminating a possible hook: what better way to commemorate May Day 2025 than with a post celebrating “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola”?

The source of these title cards is, of course, Masculine Feminine. Here’s a picture of my Criterion Collection DVD copy:

You can also stream it on the Criterion Channel and Max with subscriptions or via Prime Video for a rental fee, and some people (including current Cornell University faculty, staff, and students) may have access to it through Kanopy via a license paid for by their local academic or public library as well.

The drink, which lends itself beautifully to batching and bottling (Lee sold them out of a vending machine at his Greenwich Village bar Existing Conditions), requires advance preparation, but is otherwise dead simple. Here’s how you make it:

4 1/2 ozs. Coca-Cola Classic

2 ozs. Popcorn-infused Flor de Caña Silver Dry Rum

Infuse the rum by combining one ounce of freshly popped popcorn per 750 milliliters of rum in a nonreactive container and let sit at room temperature for one hour. Strain to remove the solids, then add one ounce of clarified butter per 750 milliliters of rum, cover, and let sit for 24 hours at room temperature. Freeze the liquid for four additional hours to solidify the butter, then fine-strain and bottle. To make the cocktail, combine both ingredients in a chilled cocktail glass filled with ice cubes.

The impression of taking a big swig of soda while your mouth is still full of movie theater popcorn is so pronounced that you may instinctively start trying to pick kernels out of your teeth! If you can’t get Flor de Caña, another smooth silver rum like Planteray 3 Stars would work just fine here as well. Finally, while I suppose you *could* use something other than Mexican Coke made with real cane sugar in this drink, I don’t know why you would.

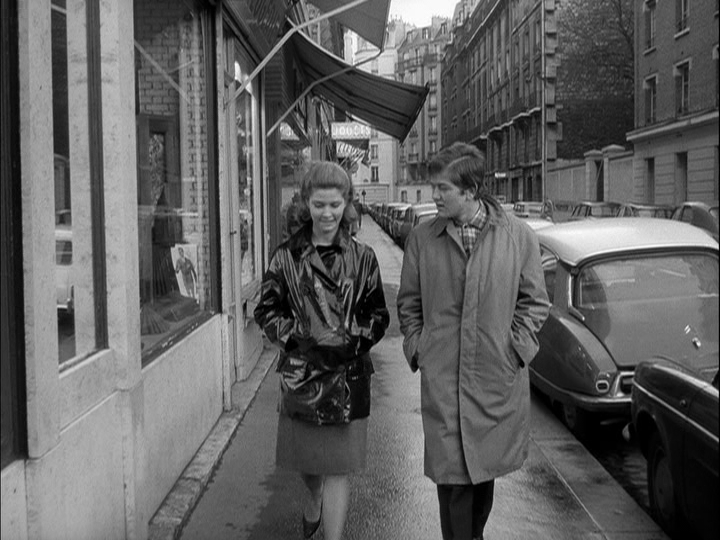

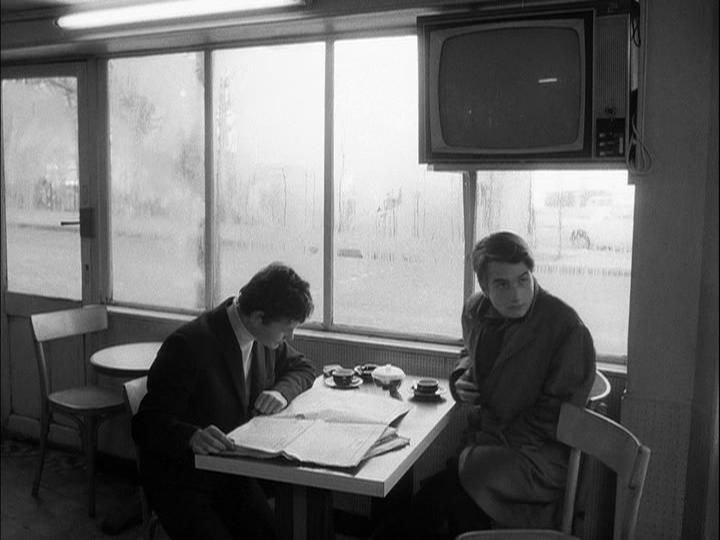

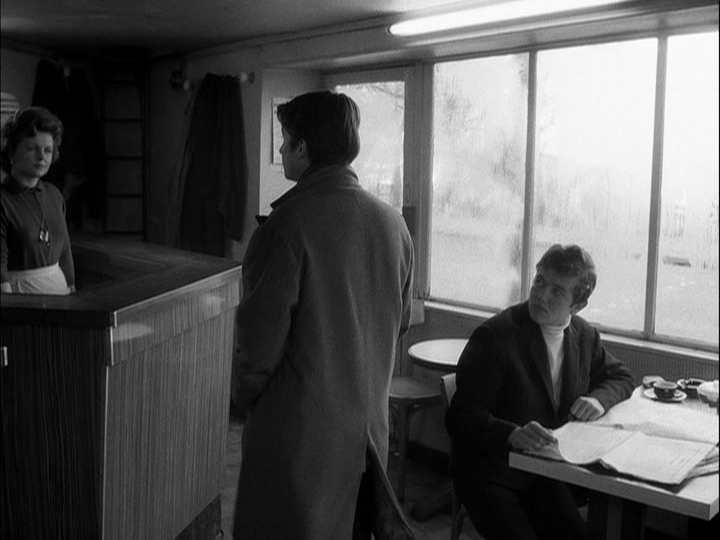

Masculine Feminine‘s Paul (Jean-Pierre Léaud) is actually a highball drinker himself, although he prefers Vittel (a brand of mineral water) and cassis.

He is shown here with Madeleine (Chantal Goya), whose character’s name also comes from Guy de Maupassant’s short story “Paul’s Mistress,” and her roommate Elisabeth (Marlène Jobert). This is one of two by the author that inspired the movie; as Richard Brody notes in his book Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard, the other manifests most directly in the form of the erotic Swedish film (which many people also interpret as a parody of The Silence) these characters go to see with their friend Catherine (Catherine-Isabelle Duport).

Despite apparently missing this connection completely, Roger Ebert surfaces another even more interesting one in his review of the 2005 American rerelease:

The movie was inspired by two short stories by Guy de Maupassant. I have just read one of them, “The Signal,” which is about a married woman who observes a prostitute attracting men with the most subtle of signs. The woman is fascinated, practices in the mirror, discovers she is better than the prostitute at attracting men, and then finds one at her door and doesn’t know what to do about him. If you search for this story in “Masculine-Feminine,” you will not find it, despite some talk of prostitution. Then you realize that the signal has been changed but the device is still there: Leaud’s character went to the movies, saw [Jean-Paul] Belmondo attracting women, and is trying to master the same art. Like the heroine of de Maupassant’s story, he seems caught off-guard when he makes a catch.

He is referring to a cigarette flip trick Paul attempts numerous times through the film (I stopped counting after five) but isn’t ever quite able to execute, making him look silly instead of cool:

“Paul’s Mistress” also shines light on how to interpret our hero’s failure to survive the film, which in her insightful contemporaneous review Pauline Kael describes as “like a form of syntax marking the end of the movie.” Or, as Godard himself says in an interview with Gene Youngblood collected in David Sterritt’s book Jean-Luc Godard: Interviews, “even though my adaptation is very different, the de Maupassant story ended with Paul’s death. But I think death is a very good answer in that kind of movie. There is no meaning in it.”

Quotations from other works abound as well, most conspicuously in the form of three members of the original French cast of Amiri Baraka’s play Dutchman (Chantal Darget, Med Hondo, and Benjamin Jules-Rosette) performing dialogue from it in character, which introduces a racial component to film’s sociological analysis of male-female relationships:

And perhaps most famously in Paul’s monologue about his generation’s relationship to the movies, which per Brody is clipped “nearly verbatim from Georges Perec’s novel Les Choses,” with Godard’s main contribution being the specific reference to American cinema:

We went to the movies often. The screen would light up, and we’d feel a thrill. But Madeleine and I were usually disappointed. The images were dated and jumpy. Marilyn Monroe had aged badly. We felt sad. It wasn’t the movie of our dreams. It wasn’t that total film we carried inside ourselves. That film we would have liked to make, or, more secretly, no doubt, the film we wanted to live.

Scenes like these, each of which would require a blog post entirely its own to fully unpack, represent Masculine Feminine at its most intricate, as does the 39 second-long sequence Richard Roud analyzes in his monograph about Godard which flips back and forth between day and night five times in a way that “more or less” parallels what we hear on the soundtrack. The first shot accompanies a voiceover by Paul in which he says, “lonely and dreadful is the night after which the day doesn’t come”:

The second, third, and fourth go along with voiceovers by Catherine and Paul’s friend Robert Packard (Michel Debord) saying, “American scientists succeeded in transmitting ideas from one brain to another, by injection” and “man’s conscience doesn’t determine his existence–his social being determines his conscience” respectively:

And finally the fourth, fifth, and sixth are paired with voiceovers by Elizabeth and Madeleine saying “we can suppose that, 20 years from now, every citizen will wear a small electrical device that can arouse the body to pleasure and sexual satisfaction” and “give us a TV set and a car, but deliver us from liberty” in turn:

Roud postulates that “one could make out a case that Godard has treated this sequence dramatically.” According to the theoretical argument he outlines, “darkness corresponds to Paul’s loneliness, to Robert’s pessimistic view of life and to Madeleine’s plea for a television-set,” while “daytime would correspond to Catherine’s rosy optimism about what science will be able to do and to Elizabeth’s Utopian future in which sexual problems will be solved by a gadget.” He believes that such ideas are “meant to be only lightly suggested,” though, and to him the real interest of this sequence is that it “shows Godard reaching towards that almost total escape from the shot as filmed” that he will achieve later in his career” and “brings out even more strongly than before that dialectical tension between reality and abstraction which forms the basis of all Godard’s later films.”

Did you get all that? I certainly didn’t my first (or second) time around, and I still don’t agree with every part of it, but the genius of Masculine Feminine is that it’s apparent that *something* is going on, which keeps you coming back to take a closer look. The fact that this is invariably rewarding is what I think Dave Kehr is talking about when he calls Godard “very strict in his sloppiness” in his capsule review for the Chicago Reader. The movie also offers many more straightforward pleasures, including an extremely animated Paul telling a Robert a story in a laundromat sequence punctuated by a panoply of jump cuts:

A hilariously cheeky depiction of him “putting himself in someone else’s shoes” by copying the actions of man who asking for directions to the local stadium:

Paul telling the story of how his father “discovered” why the earth revolves around the sun, an experience I myself had in a third-grade science class when I figured out where rainbows come from seconds before the teacher explained it to me and my fellow students:

And Chantal Goya’s songs, which are crucially far more interesting than any statement Paul or Robert ever makes on screen.

Penelope Gilliatt called Masculine Feminine “the picture that best captures what it was like to be an undergraduate in the sixties” in an article for The New Yorker, but moments like these are remarkable because they also feel timeless to one like me who went to college in the early 2000s. As do, sadly, the random acts of political and tabloid violence that Gilliatt speaks of next: “five deaths recorded; total apathy expressed by the characters.” Only two are depicted, a woman shooting her husband outside a café:

And a man (Yves Afonso) who appears to be about to mug Paul before he suddenly turns his knife on himself:

Non-diegetic gunshots also appear throughout on the soundtrack, though, which Adrian Martin describes in his essay for the Criterion Collection as “harsh aural interruptions, firing at unpredictable points” that represent “the violence of everyday modern urban life” in concentrated form. Can you blame Paul if he’s so inured to it that he’s more worried about the draft coming in through an open door than the murder taking place outside of it, or about his matches than the man about to immolate himself with them in protest of the Vietnam War? Maybe so, but my point is that while Godard, who styled Masculine Feminine a “concerto on youth” in an interview with Pierre Daix collected in the Grove Press film book about it, may not approve of his protagonists playing at pop stardom and philosophy while the word burns, he (to paraphrase another great work of music) obviously understands that they didn’t start the fire.

One of the movie’s most talked-about shots is Paul’s single take interview with “Miss 19” (Elsa Leroy), which lasts nearly seven minutes and is introduced by a title card which reads “dialogue with a consumer product.”

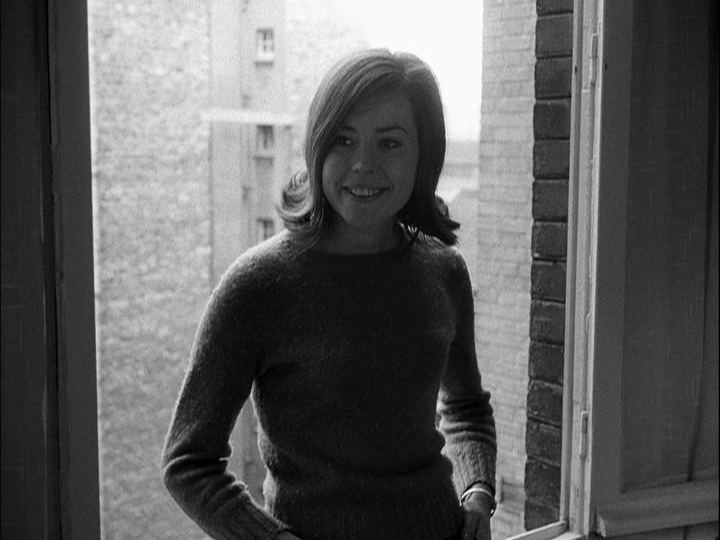

His questions are seemingly designed to reveal her ignorance about current events, but as Stephanie Zacharek observes in her 2005 review, “the scene is fascinating because although on the surface it seems Godard is asking us to join in ridiculing this girl, in the end it’s Paul’s vulnerability and naiveté that are exposed.” He is also every bit as concerned with his image as Madeleine is, it’s just that where she’s specifically focused on hair and makeup:

He’s attuned to the power of mise-en-scène in all its dimensions (remember that cigarette prop?) and nearly scraps a marriage proposal entirely when he can’t make the location he has scouted work:

It really is too bad that Masculine Feminine‘s boys map so clearly and simplistically to Godard’s notion of the “children of Marx” and its girls to the progeny of Coca-Cola, but it strikes me as a major stretch to say that the former come away looking better than the latter, especially when, as Ed Gonzalez points out in his Slant Magazine review, the ladies get the final word: “the last shot of the film acts as a female-empowering solution to Godard’s philosophical algorithm of the sexual politic. FIN.”

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.