From where I’m standing the net impact of expanded legalized sports betting has clearly been negative. Research shows that it results in increased levels of debt for individual consumers, athletes are subject to unconscionable levels of abuse because of it, and the constant barrage of ads and ridiculous celebrity parlays makes the experience of watching sports on TV less fun. For all of these reasons I’d probably support more regulation at this point despite my libertarian inclinations, but as long as it remains so easy to place a bet, I will selfishly continue to enjoy doing so during certain times of year. March is one of them because of the NCAA Tournament, so lately I’ve been thinking about my favorite titular (which disqualifies Howard Ratner) movie gambler, Bob Montagné (Roger Duchesne). Here’s a picture of my Kino Lorber DVD copy of the film he lent his name to, Bob le Flambeur:

It is also available for rental from a variety of other platforms, and some people (including current Cornell University faculty, staff, and students) may have access to it through Kanopy via a license paid for by their local academic or public library as well.

The drink I’m pairing it with was created by Natasha David as boozy version of her favorite thing to eat, “dark, bitter chocolate.” Here, per Imbibe, is how you make her All In (which for the uninitiated is a poker term which refers to the act of pushing all of one’s chips into the middle of the table) cocktail:

1 1/2 ozs. Rye (Pikesville)

3/4 oz. Campari

3/4 oz. Dry vermouth (Dolin)

1/4 oz. Crème de cacao (Tempus Fugit)

Stir all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Express a lemon twist over the top and discard.

This concoction’s nose is dominated by lemon from the twist, and my brain therefore immediately latched on to the citrus notes in the Campari and Dolin on the sip. There’s also a lot of burn from the rye, though, which combines to create an initial impression not unlike drinking grappa. The swallow and finish are all very dark (think 85+% cacao) chocolate. David specifies rye that is 100-proof or higher, making this a perfect place to showcase Pikesville, which clocks in at 110 and is totally my jam these days. She also described her goal being “to create a dry chocolate cocktail that wasn’t limited to a dessert drink—a cocktail that could be enjoyed any time of the day,” and in that regard the All In is a resounding success.

Bob would appreciate this beverage, as he is no stranger to imbibing during the daylight hours. Here, for instance, we see his best laid plans for breakfast being waylaid by a tempting bottle of wine:

His luxurious apartment, which has one of the best views in the history of cinema and a slot machine in the closet:

“Absolutely massive American car,” as Nick Pinkerton says in his DVD commentary track (where he also identifies it as a 1955 Plymouth Belvedere):

And the fact that he appears to have a standing invitation to join any high-stakes game in Paris all suggest that he must have been more disciplined in his youth, but he is become, in the words of his best friend Roger (André Garet), a “pitiful” compulsive gambler who squanders every big win by taking his profits elsewhere and promptly losing them.

Because he does so in style, though, and according to a moral code that includes generosity to those even less fortunate as one of its primary tenets, he nonetheless remains an idol to the young men in his circle like Paolo (Daniel Cauchy), whose late father knew Bob back in his gangster days:

A hero to young women like Isabelle Corey’s Anne, to whom he provides pocket money and a place to sleep with no expectation of repayment in any form:

And the object of fraternal or maternal affection from compatriots like Roger and Simone Paris’s Yvonne, who purchased her café with a loan from him:

As well as the recipient of professional courtesy from René Havard’s Inspector Morin of the police, whose life he once saved:

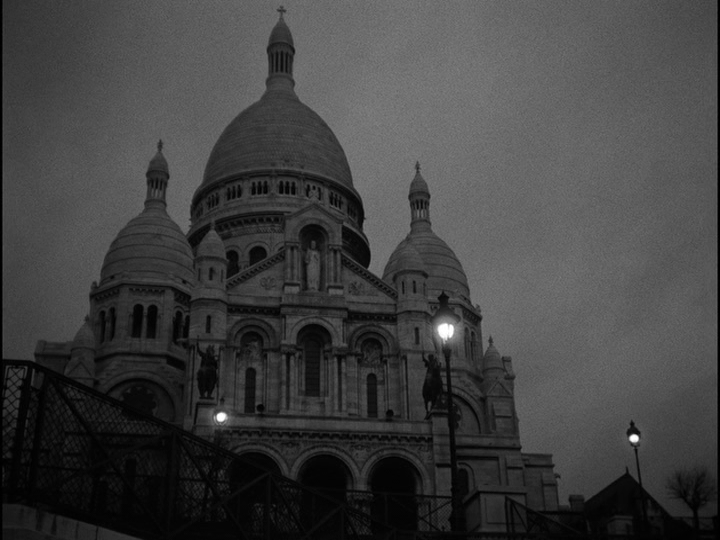

If you didn’t know this was a caper movie, you’d never guess it from the first 37 minutes, which function more as a sort of nature documentary showing Bob in his natural environment. As Glenn Erickson observes in his review of Kino Lorber’s 4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray copy of the film which came out last year, the location shooting makes it “a literal time capsule of a long-gone Montmartre, a collection of nightclubs and bars where colorful, unsavory night crawlers plot their next moves.” It begins with a monologue that characterizes the Parisian neighborhood as “both heaven and . . . hell” with the image of a descending funicular and accompanying musical cue during the ellipse.

Anne is introduced as an illustration of how “people of different destinies” cross paths in the pre-dawn hours not by name, but as a girl “with nothing to do” who is “up very early . . . and far too young” who passes a cleaning lady hurrying to work on the street:

Finally, we meet Bob playing craps in an establishment featuring the first example of what J. Hoberman calls “the insistent checkerboard patterns that make the movie so emphatically black-and-white”:

They appear again on the walls of Roger’s office, where author of A History of the French New Wave Cinema Richard Neupert argues they function “to remind the viewer that Bob, with his flowing white hair, sees the world as one big board game”:

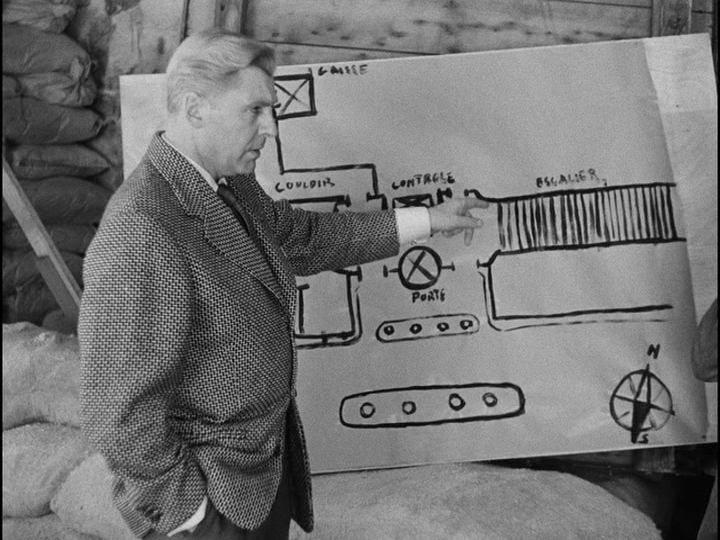

Per Neupert, Bob le Flambeur inspired the French New Wave with its “raw, low-budget style that mixes documentary style with almost parodic artifice.” My favorite examples of both tendencies can be found in the rehearsals which lead up to the attempted robbery that Bob begins to plan after he learns that the safe in the Deauville casino will have 800 million francs (which as near as I can work out is about 20 million USD today) at 5am the morning of the upcoming Grand Prix race. After he and Roger find someone (Howard Vernon as McKimmie, who insists on a 50% cut of the take) to finance their operation in the first of many scenes that the 2001 remake of Ocean’s Eleven directed by Steven Soderbergh pays homage to, the “recruitment waltz” begins:

With their team assembled, they set about casing the joint by circling it repeatedly in a car and sketching an outline in a minute-long scene that embodies the “documentary style” Neupert describes:

They also obtain blueprints and specs which they use to obtain a safe so that Roger can practice opening it:

And best of all draw chalk outlines of the casino on a grass field so that they get an accurate sense of the space:

We also see Bob’s vision of how the operation is supposed to in a casino of empty of anyone except him and his crew, a technique borrowed by my July, 2023 Drink & a Movie selection Inside Man among scores of other films:

We never see the actual heist, though, because although Bob arrives at the casino to scope things out at 1:30am as planned in a stylish low-light sequence:

Instead of making contact with Claude Cerval’s Jean, their guy on the inside, like he’s supposed to, he forgets his promise to himself and Roger not to gamble until it is over and places a bet:

He wins, so he places another, this time at odds of 38 to 1:

That hits, too:

And suddenly Bob is off on the heater of his life. The voiceover informs us although the roulette is over by 2:01, “the chemin de fer continues”:

He is successful there, and at 2:45 he enters a the high-rollers room:

It’s difficult to say for sure how much he wins there, but by 3:30 he has attracted a crowd of onlookers:

And not long after that, he’s tipping the croupier one million francs at a time:

Based on the stacks of chips in shots like this, it appears that Bob’s winnings total nearly as much as the 400 million francs he and his crew are expecting to make from robbing the casino. Suddenly he chances to look at his watch and sees that it’s 5am:

He shouts, “change all this, now!” and sprints to the entrance, but it’s too late: the police, tipped off by Jean and his wife (Colette Fleury) and an informant (Gérard Buhr) armed with details that Paolo carelessly let slip to Anne, are waiting for Bob’s crew when they arrive and Paolo dies in the shootout which ensues:

Bob arrives just in time to cradle his protege in his arms as his life expires:

As Inspector Morin places Bob and Roger in handcuffs, one of his officers removes a coin from Bob’s pocket that we saw him flipping earlier.

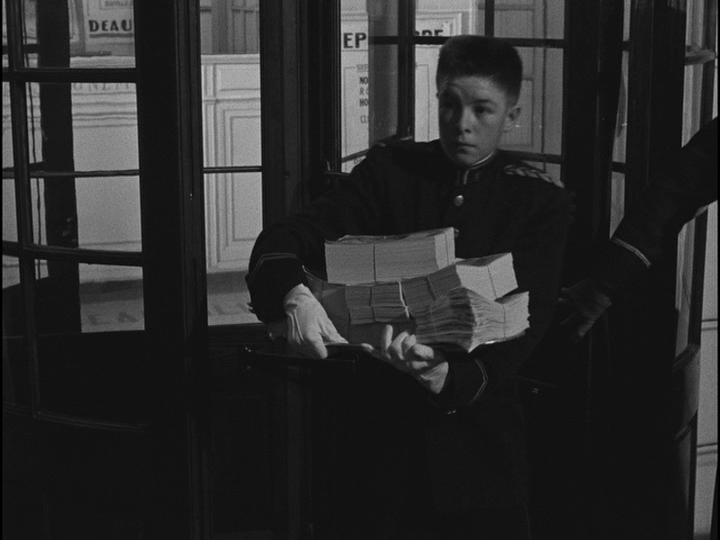

“I’ve known it was double-headed for ten years,” Roger tells him. “And I’ve known you knew for ten years,” Bob replies. “Paulo knew too,” he adds. Just then the somber mood is broken by a procession of bellhops bringing out Bob’s winnings:

“And don’t let any of it go missing!” Bob says as he is led into a squad car. “Criminal intent to commit . . . you’ll get five years,” Morin says as he offers Bob and Roger cigarettes.

“But with a good lawyer, you might get away with three years,” he continues. “With a very good lawyer, and no criminal intent, maybe an acquittal!” Roger adds. And finally Bob: “If I play my cards right, I might even be able to claim damages!” The movie ends with a amazing shot of his car sitting in front of the Deauville shore as the sun rises behind it:

Dave Kehr writes in an essay that appears in his book When Movies Mattered that “[director Jean-Pierre] Melville is often described as an existentialist, but to execute a scene like the finish of Bob le Flambeur, even in jest, you need to have some faith in the basic benevolence of the world–some faith in a higher, protective power, such as the ‘luck’ that Bob turns his back on and that then returns, in the end, to save and reward him after all.” I couldn’t agree more with the first part of this statement, but would quibble just a bit with the latter. Bob never *abandons* Lady Luck; rather, ever the gentleman, he tries to take a hint and move on when it seems like he has lost her favor, but when he realizes his error, he’s more than happy to come home. As the voiceover remarked earlier as the seconds ticked down to 5:00, “that’s Bob the gambler as his mother made him!” I noted last February in a post about The Young Girls of Rochefort that a friend has suggested that the theme of this series is “the human experience of trying to become a better person.” I suppose that must make Bob le Flambeur another exception to this rule.

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.