Between Valentine’s Day in February and Easter in March/April, I think it’s fair to say we’re in the “chocolate quarter” of the calendar year! In honor of such, this is the first of three Drink & a Movie posts in a row that will feature a drink made with one of my favorite underrated heroes of the back bar: crème de cacao. As Paul Clarke notes in The Cocktail Chronicles, its bad reputation is likely attributable “the substandard quality of many chocolate liqueurs” prevalent on the market until Tempus Fugit Spirits’ version became widely available about ten years ago. It and the Giffard white crème de cacao that I prefer in the 20th Century cocktail I wrote about in 2022 for reasons of color are both excellent, though, and there’s no longer any use to shy away from this ingredient. As described in a post on his blog, Clarke created this month’s drink, the Theobroma, as his version of a chocolate martini. Here’s how to make it:

2 ozs. Reposado tequila (Mi Campo)

1/2 oz. Punt e Mes

1/4 oz. Bigallet China-China

1 tsp. Crème de cacao (Tempus Fugit)

2 dashes Bittermens Xocolatl Mole Bitters

Stir all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with an orange twist.

The Theobroma begins with orange on the nose and an impression of sweet and bitter on the sip which quickly comes into focus as agave and chocolate. “Definitely a tequila drink,” said My Loving Wife, and I wouldn’t want to use something much more assertive than Mi Campos, which in my opinion is currently the best value in the reposado category available here in Ithaca, NY. It is rested in wine barrels, which contributes vanilla flavors also prominent in Tempus Fugit’s crème de cacao that come through on the swallow along with spice and more orange. Clarke’s description of his concoction as “a bold, elbow-throwing mixture that’s unafraid to let its chocolate flag fly” is spot-on, and I’m not going to try to improve on it!

Believe it or not, the chocolate martini was created by actors Rock Hudson and Elizabeth Taylor on the set of the movie Giant. The book Rock Hudson: His Story contains the tale:

Rock and Elizabeth stayed in rented houses across from each other, and it was in one of those houses on a Saturday night in 1955 that they invented the chocolate martini. They both loved chocolate and drank martinis. Why not put chocolate liqueur and chocolate syrup in a vodka martini? They thought it tasted terrific and made a great contribution to society until they began to suffer from indigestion. “We were really just kids, we could eat and drink anything and never needed sleep,” Rock said.

Given these origins, what better film to pair with the Theobroma than a riff on the Rock Hudson vehicle All That Heaven Allows that hails from Germany, “the land of chocolate,” and involves stomach problems as a plot point? I am, of course, referring to Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. Here’s a picture of my Criterion Collection DVD:

It is also streaming on the Criterion Channel and Max with a subscription, can be rented from a variety of other platforms, and some people (including current Cornell University faculty, staff, and students) may have access to it through Kanopy via a license paid for by their local academic or public library as well.

As Klaus Ulrich Militz writes in his book Personal Experience and the Media, the relationship between Ali: Fear Eats the Soul and All That Heaven Allows “is not as clear as it may seem at first.” For starters, although both films revolve around a May-December romance, director Rainer Werner Fassbinder must have conceived of his movie before he encountered its supposed inspiration for the first time in autumn 1970 because “a rough outline of the film’s story-line is told by the chambermaid in the film The American Soldier,” which he shot two months earlier. The fact that his protagonists Emmi (Brigitte Mira) and Ali (El Hedi ben Salem) enter into a relationship with each other at the beginning of it also represents a major structural break with the earlier movie directed by Douglas Sirk, which “largely follows the emancipatory logic of the melodramatic genre because his heroine only gradually manages to overcome her passivity before she eventually commits herself to her lover.” Nonetheless, per Militz, “the fact remains that when Fassbinder eventually made Ali: Fear Eats the Soul in 1973 this was done under the impression of Sirk’s films.”

One place many people feel the influence of All That Heaven Allows is in Fassbinder’s use of color. For instance, in her chapter for the book Fassbinder Now: Film and Video Art, Brigitte Peucker observes that the “formal, conformist grey clothing” that Emmi and Ali get married in marks them as “constrained by the social order,” but that it’s offset “by the Sirkian red carnations that emblematize emotion”:

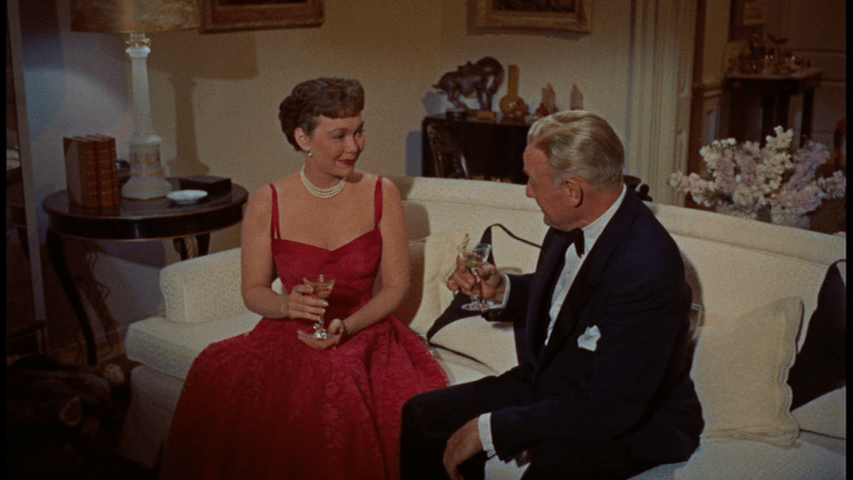

This seems to echo what Brian Price describes in his chapter for the book A Companion to Rainer Werner Fassbinder as the typical reading of the vibrant red dress Jane Wyman’s Cary Scott wears in Heaven to show “what remains inside and–owing to social constraints–invisible.”

As he notes, though, Emmi’s flowers are different in that “Fassbinder’s colors, unlike Sirk’s, tend toward disharmony and away from the kind of color coordination that makes analogy possible.” Pointing out that the man Cary is with in the image above, Conrad Nagel’s Harvey, is wearing clothing that matches the furniture they are sitting on, Price argues that this provokes a simile: “Harvey, we might say, is like a couch, something to rest on, something solid but soft, immovable–and worst of all for Harvey, something inanimate, or merely functional.” Contrast this with the dresses Emmi favors elsewhere in Ali, such as the one she has on as she sits “in front of an amateur painting of horses running executed in pale yellow gold tones decidedly less bold than the ones Emmi wears” and curtains “which are no less busy than her dress but are nevertheless discordantly situated with respect to it–baby blue instead of navy blue, a dull grayish green instead of the saturated green to which it stands, in the overall composition, in odd contrast”:

To Price “the contrast eludes metaphor” and because “this green is not like that green, then Emmi cannot be defined by the objects and spaces that constitute her on a contingent–and thus reversible–basis.”

My Loving Wife explained to me that this is also a wrap dress like the one designed by Diane von Furstenberg, which per this Time Magazine article she created “for the kind of woman she aspired to be: independent, ambitious, and above all, liberated.” Fascinatingly, it also states that “von Furstenberg was told from a young age that ‘fear is not an option.'” The similarity of that quote to the title of this month’s movie may be just a coincidence, but Emmi’s fashion sense surely isn’t, especially when you consider how many of these garments she has in her wardrobe:

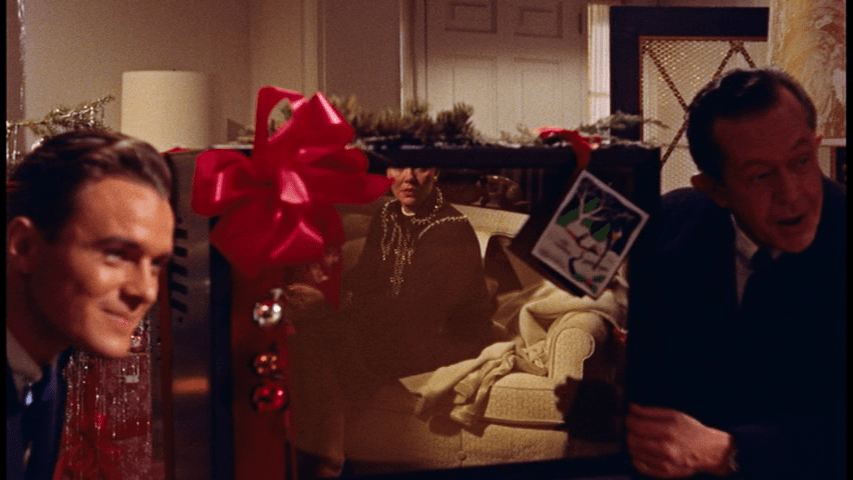

Fassbinder similarly uses the television and frames within frames that appear in Heaven, represented here by a single powerful camera movement:

As a launchpad to do his own thing. He transforms the TV from a would-be prison cell into an symbol for the respectable German family that Emmi’s son Bruno (Peter Gauhe) believes she has disgraced with her choice of husband:

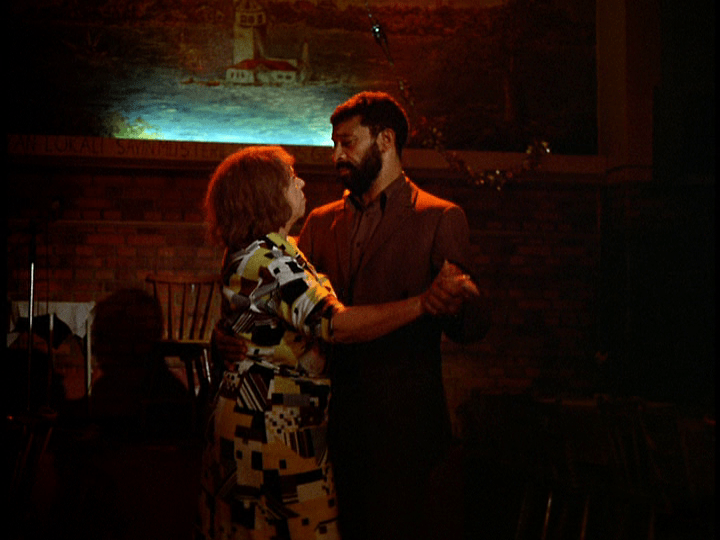

Meanwhile, almost every other aspect of the film’s mise-en-scène is a cage. This includes the wedding where Ali and Emmi celebrate their wedding:

The apartment and bedroom where Ali seeks solace (and couscous!) after his relationship with Emmi calcifies into yet another instrument of exploitation:

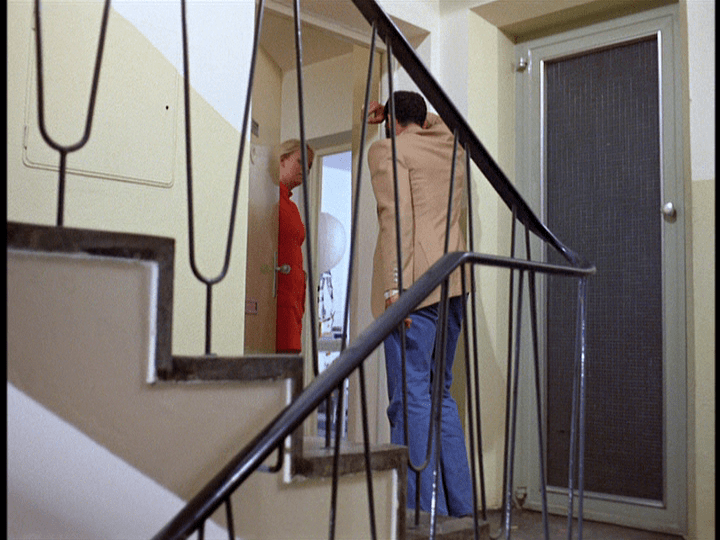

The stairwell where Emmi eats lunch alone after being shunned by her charwomen:

Then, once back in their good graces, joins them in giving the cold shoulder to their new co-worker Yolanda (Helga Ballhaus), a Herzegovinian immigrant:

And a shot-reverse shot of a nosy neighbor (Elma Karlowa) watching Ali and Emmi mount the stairs of her building that, Manny Farber writes in an essay collected in the book Negative Space, “suggests all three, like all Fassbinder’s denizens, are caught in a shifting but nevertheless painful power game of top dogs and underdogs”:

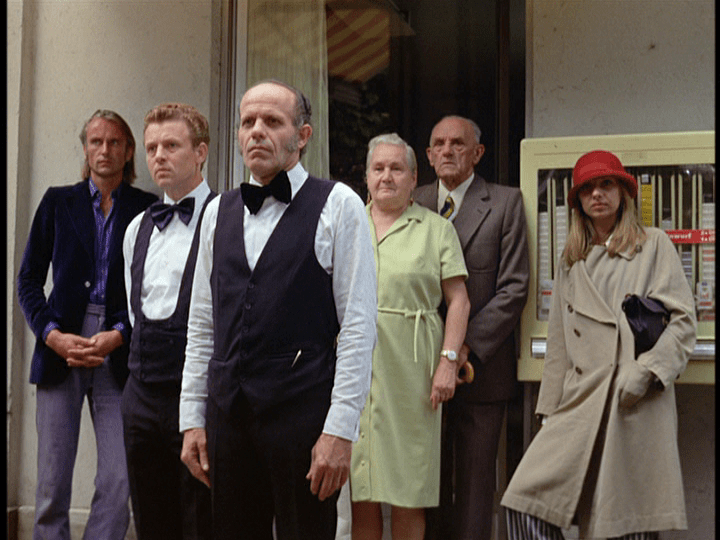

But my favorite aspect of Ali is reminiscent less of Sirk than something Richard Jameson once said about the movie Once Upon a Time in the West. He described it as “an opera in which arias are not sung but stared,” and that’s a perfect fit for this film as well! You can practically hear the thoughts of Asphalt Bar proprietress Barbara (Barbara Valentin) as she sizes up Emmi, who has appeared in her establishment for a second time hoping to find Ali:

And those of the waiter (Hannes Gromball) at the restaurant “where Hitler used to eat from 1929 to ’33” (!) as he contemplates his unusual customers:

“Sometimes, long silences seem to be an expression of the social hostility encountered by Emmi and Ali, as in the climactic scene in an outdoor cafe immediately before their regenerative vacation,” notes James C. Franklin in a Literature/Film Quarterly article called “Method and Message: Forms of Communication in Fassbinder’s Angst Essen Seele Auf“ (the movie’s German title) where “the interaction of the visual image and the silence creates an atmosphere of utter coldness and hostility”:

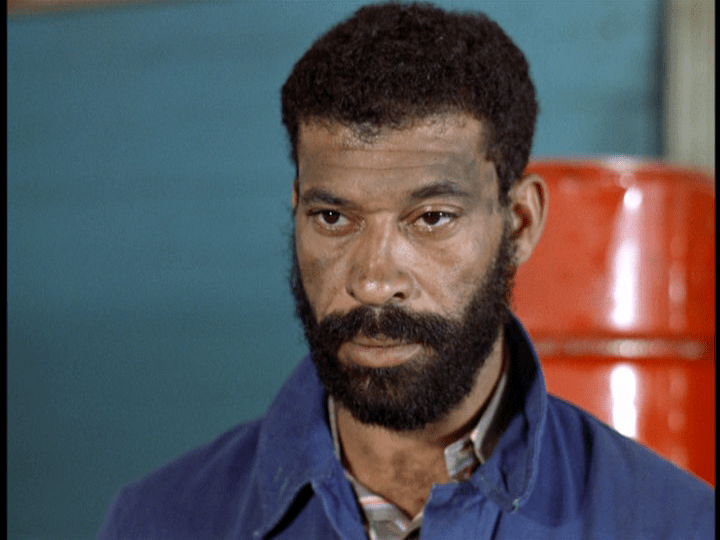

However, my favorite examples of where (as Franklin eloquently puts it) “there is much to be heard in the silence of the soundtrack” are the looks Ali and Emmi give each other the morning after he first comes back from a night out blackout drunk:

And then doesn’t arrive home at all:

The latter occur in the film’s final ten minutes. In a response to a chapter in Robert Pippin’s book Douglas Sirk: Filmmaker and Philosopher for the national meeting of the American Society for Aesthetics that he posted on Letterboxd, Matt Strohl comments on a phenomenon that he calls the “double ending” of subversive melodramas whereby “an ostensible happy ending is subverted by some unsettling element, which might then prompt us to reflect on whether it was really such a happy ending after all and to reinterpret the film in this light.” Although All That Heaven Allows concludes with Cary resolving to “come home” to her lover Ron (Hudson), both scholars argue that we should feel uneasy about this, Pippin (as paraphrased by Strohl) because Cary “did not make the decision to enter into this relationship” but rather “fell into it because of Ron’s newfound need for a caretaker” and Strohl because “Cary has not gotten over her fears and become a full-fledged agent, but rather has slid into a different socially-defined gendered role that she has not actively chosen.”

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul is a different kind of beast. The scene after the second staredown depicted above opens with Ali “gambling away a week’s wages” (as Barbara points out to him) at the Asphalt Bar:

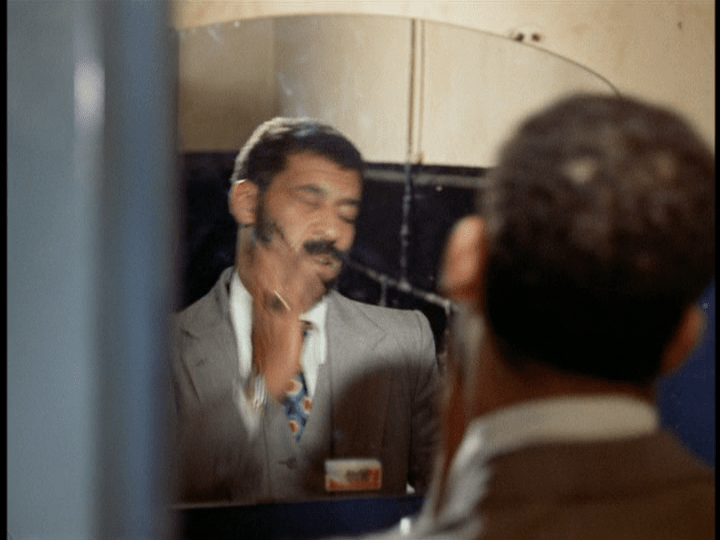

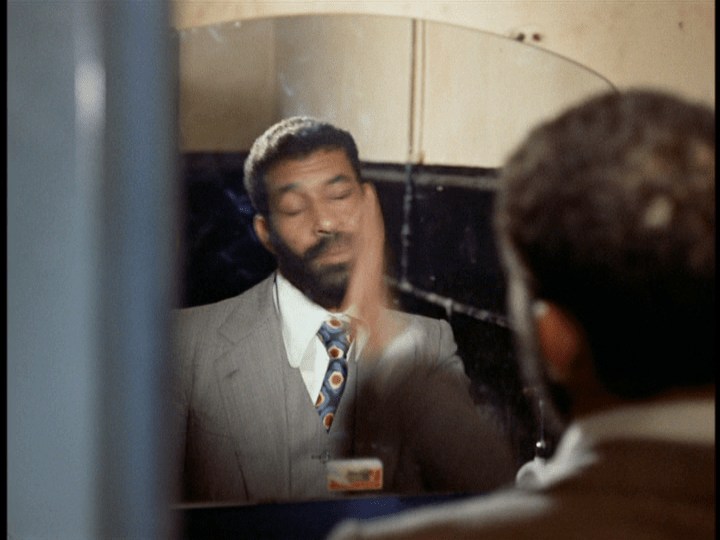

He busts out and sends a friend to his place for 100 more marks. While he waits for the money, Ali goes to the restroom and proceeds to slap himself in the face multiple times in a weird twist on Jackie Gleason’s Minnesota Fats freshening-up routine in The Hustler:

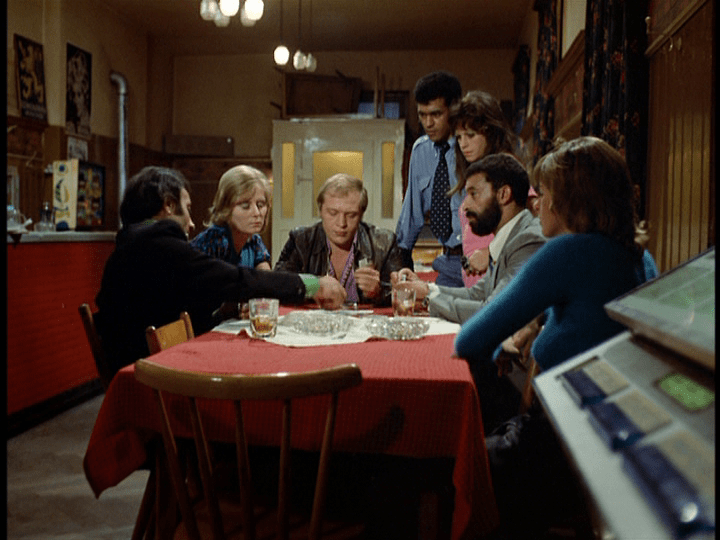

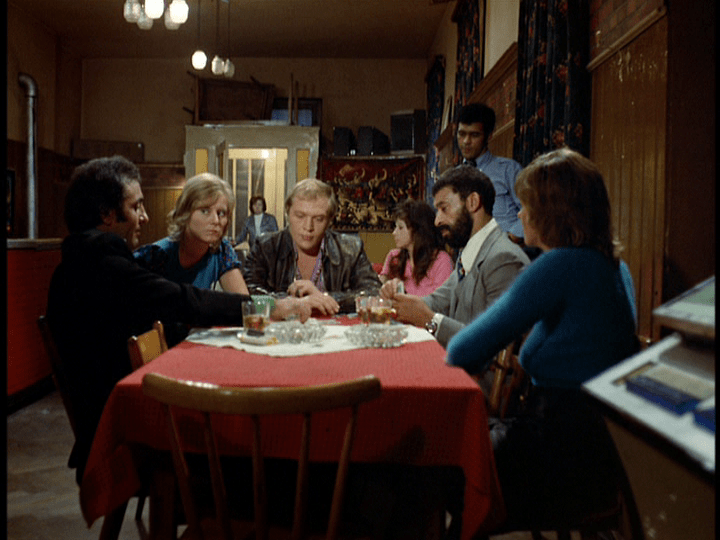

As he sits back down at the table and immediately proceeds to lose a hand, Emmi enters the bar in the background:

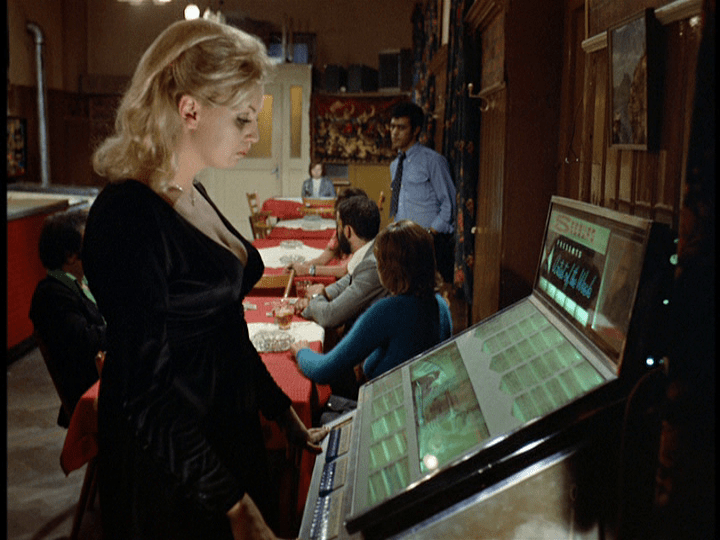

Barbara brings her a Coke, the drink she ordered the night she met Ali, and Emmi asks her to play the tune they later danced to. Ali and his companions stare at Emmi as Barbara selects the song on the jukebox in the foreground of a three-layer composition:

As soon as the music begins playing, Ali stands up and asks Emmi to dance. As the sway back and forth he confesses that he has slept with other women, but she assures him the it isn’t important and that he’s a free man who can do as he likes. “But when we’re together, we must be nice to each other,” she says. “Otherwise, life’s not worth living.”

“I don’t want other women,” he responds. “I love only you.” Suddenly, he collapses to the ground, moaning in pain:

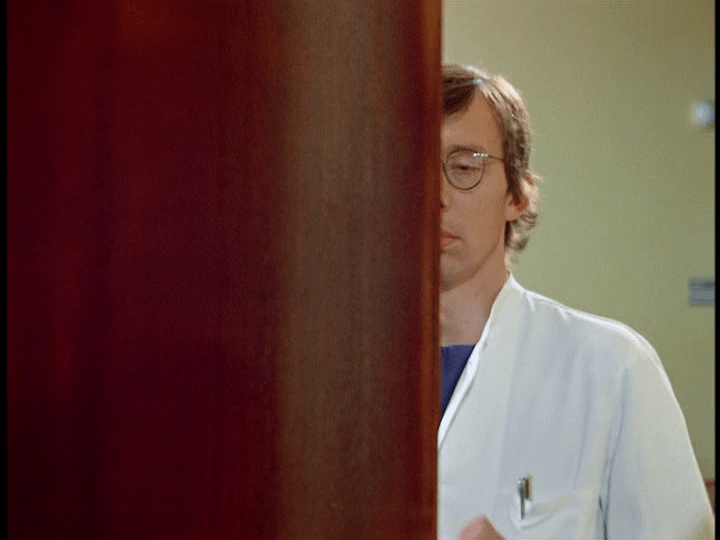

The final scene takes place in a hospital. “He has a perforated stomach ulcer,” a doctor (Hark Bohm) tells Emmi. “It happens a lot with foreign workers. It’s the stress. And there’s not much we can do. We’re not allowed to send them to convalesce. We can only operate. And six months later they have another ulcer.”

“No he won’t,” Emmi insists. “I’ll do everything in my power. . . . ” The clearly skeptical doctor interrupts her: “Well, the best of luck anyway.” Emmi walks over to Ali and the camera tracks in on their reflection in the mirror:

The doctor closes the door:

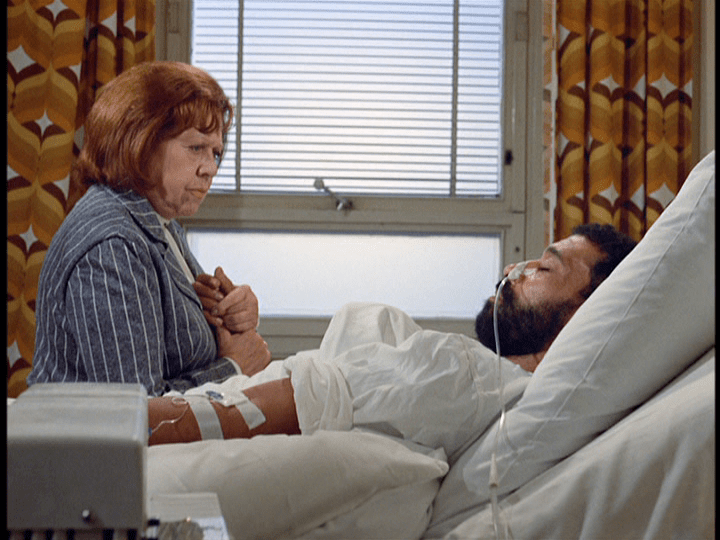

And the film ends with a shot of Emmi crying as she holds an unconscious Ali’s hand:

The utility of the “double ending” for Strohl is that it can explicate an otherwise inchoate sense that “there’s something off” about a Hollywood ending. There’s obviously no need for that here, but if broaden this concept and reinterpret it through the lens of the drink writing idea of a “finish,” it can also give voice to whatever lingers in your mind after the final credits have rolled. Ali‘s finish is the same as the Theobroma’s: they’re both bittersweet, which, if you don’t think that’s appropriate to the Valentine Season, you’ve never really been in love.

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.