The San Francisco Nog created at Waltham, Massachusetts bar Deep Ellum has been a favorite in our house ever since Frederic Yarm wrote about it on his Cocktail Virgin Slut blog a few years ago. With Fernet Branca on my mind, it was natural that my thoughts would also turn to San Francisco, since for reasons Grant Marek chronicled for SFGate that spirit is linked to the city “in the same way that Malort is to Chicago and Guinness is to Dublin, Ireland.” This led me to a movie filmed there that I’ve been entranced with ever since I encountered stills from it in David Cook’s A History of Narrative Film as an undergraduate film studies major: The Lady from Shanghai. A dairy-based beverage would be a terrible fit for its hot and sweaty first half, so instead I’m taking a cue from the yacht the Circe which belongs to the titular lady Elsa Bannister (Rita Hayworth) and her husband Arthur (Everett Sloane) and pairing it with the Don’t Give Up the Ship cocktail that most drinks historians agree first appeared by that name (there’s also a concoction called a Napoleon in The Savoy Cocktail Book with the exact same ingredients) in Crosby Gaige’s 1941 Cocktail Guide and Ladies Companion, but which, like the Last Word I wrote about in 2023, owes its present-day popularity to Seattle’s Zig Zag Cafe.

As Jason O’Bryan noted in The Robb Report, there are now two versions of the drink. He favors the rendition made with Cointreau and sweet vermouth, but My Loving Wife and I enjoy the one that features Grand Marnier and Dubonnet Rouge more. He’s actually a fan of both and describes the original as “a lower-toned winter drink,” which is obviously appropriate to the season, and we think it’s a better platform for the fernet as well. Using a movie comparison that I appreciate as a child of the 90s, O’Bryan speculates on his Drinks and Drinking blog that this “may be a Happy Gilmore/Billy Madison situation.” Anyway, the recipe by Zig Zag’s Ben Dougherty which O’Bryan and others link to is no longer on Food & Wine magazine’s website, but you can still find it in their 2007 Annual Cookbook. Here’s how to make it:

1 1/2 ozs. Gin (Junipero)

1/2 oz. Dubonnet Rouge

1/4 oz. Grand Marnier

1/4 oz. Fernet Branca

Stir all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled glass.

Junipero is ideal here because it’s made in San Francisco and also matches O’Bryan’s call for a “big, robust, juniper-forward” selection. In addition to being delicious, Grand Mariner is also made with a brandy base, which as Eddie Mueller says in his description of the Sailor Beware cocktail he created to pair with The Lady from Shanghai for his Noir Bar book seems “a likely libation for sinister shyster Arthur Bannister.” Both the gin and fernet are very prominent, so steer clear if you aren’t a fan of those ingredients. But if, like us, you love them: full speed ahead! On to the film. Here’s a picture of my TCM Vault Collection Blu-ray/DVD:

It can also be rented from a wide range of streaming video platforms.

Dave Kehr famously called The Lady from Shanghai “the weirdest great movie ever made,” but as James Naremore writes in his book The Magic World of Orson Welles, “its strangeness did not result from an early, deliberate plan.” Instead, he argues that as a result of some combination of interference by Columbia Pictures and the “weariness, contempt, or sheer practical jokery” of its director, “the movie seems to have been made by two different hands.” Naremore points to the fact that it was “reduced by almost an hour from its prerelease form” and “substantially revised” at the behest of studio chief Harry Cohn (who allegedly offered $1,000 to anyone who could explain its plot to him after viewing the rough cut) as his primary evidence for this, but I haven’t read anywhere that Welles ever intended to edit the film himself and it’s hard to know for sure what exactly a finished version that he had more say in might have looked like. Based on the interviews with him that Peter Bogdanovich compiled into the book This Is Orson Welles and reads from on the commentary track on my DVD, for instance, the single-take version of the opening Central Park sequence (which American Cinematographer reported set a record for the longest dolly shot ever filmed) was always destined to be cut apart and down. It’s also not as if every shot overseen by Welles that made the final cut is beyond reproach. As Naremore says about one that I’m unfortunately no longer able to not see, the decision to use a panning movement which causes the jagged edges of glass at the corners of the frame below to move “is clearly a director’s error”:

Welles’s biggest objection seems to have been to the music by Heinz Roemheld, exemplified for him by the “Disney”-esque glissando added to this dive:

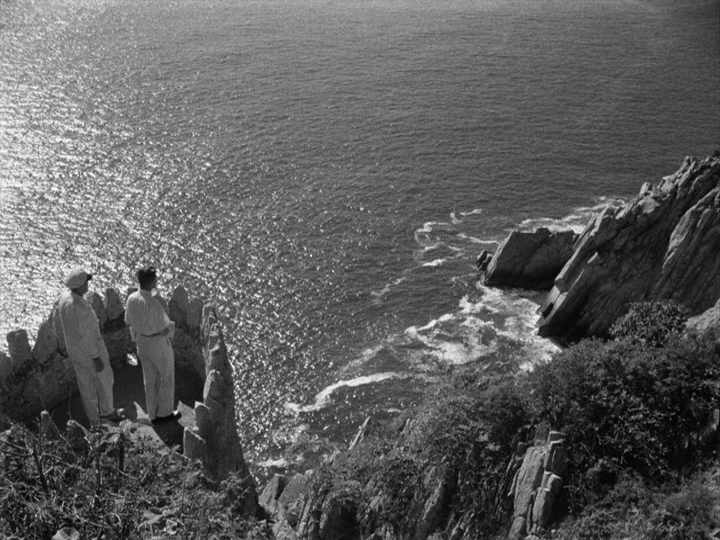

And although I don’t actually have a problem with the way the climactic Magic Mirror Maze shootout sounds today, it’s hard not to be intrigued when Welles tells Bogdanovich that it “should have been absolutely silent except for the crashing glass and ricocheting bullets–like that, it was terrifying.” Even more obviously tragic are the cuts from the final shooting script for the Acapulco sequence which Naremore describes in Biblical terms as depicting Glenn Anders’s George Grisby “tempting” Welles’s Michael O’Hara atop a mountain:

As Grisby and O’Hara stroll up the hillside from the beach, Grisby’s remarks are systematically played off against American tourists in the background, whose conversations about money become obsessive and nightmarish. We see a little girl attempting to get her mother to buy her a fancy drink. “But mommy,” she says, “it ain’t even one dollar!” Then a honeymoon couple walks past. “Sure it’s our honeymoon,” the young man says, “but that’s a two-million dollar account.” An older lady and her husband cross in front of the camera, arguing about taxi fare. “I practically had to pay him by the mile,” the lady complains. A gigolo speaks to a girl seated on a rock. “Fulco made it for her,” he announces. “Diamonds and emeralds–must’ve cost a couple of oil wells. And she only wears it on her bathing suit.” Another young couple walks up the steps from the beach, the man rubbing his nose with zinc oxide as he mutters, “but listen, Edna, you’ve got to realize pesos is real money.” Two girls enter the scene, one of them saying “Heneral–that means General–in the army like. Only this one’s rich.” Meanwhile, through all of this, Grisby babbles about the atomic bomb and the end of the world, ultimately turning and asking O’Hara, “How would you like to make five thousand dollars, fella?”

All that remains of this dialogue are the line from the gentleman afraid of sunburn and the Spanish lesson (although you can also see a couple of the other characters) and as a result all of this meaning is pretty much entirely lost.

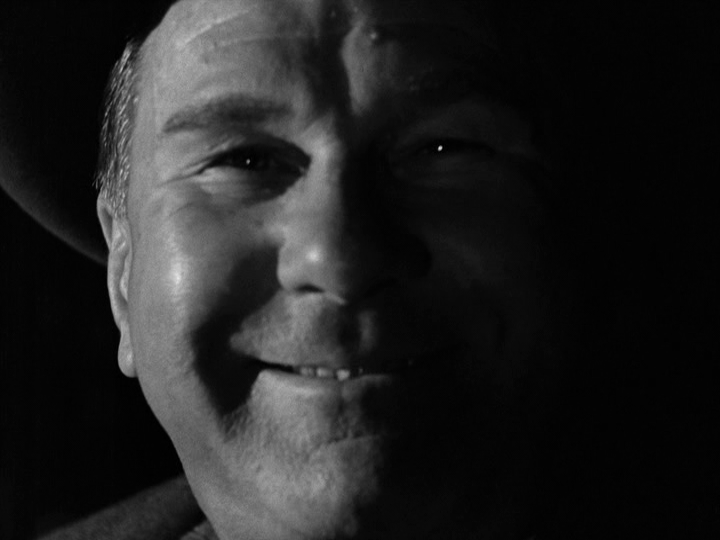

And yet! This scene is nonetheless burned into my memory because it ends with one of my favorite shots in the whole history of cinema. Grisby explains that all Michael needs to do to earn the money he’s offering is to kill someone. “Who, Mr. Grisby?” O’Hara asks. “I’m particular who I murder.” Cut to a sharp-focus close-up of Grisby’s face that contrasts strikingly with a softer one of Michael’s, which Naremore argues is an example of how “glamorous studio portrait photography contributes to the film’s aura of surrealism:

“It’s me,” Grisby says. What follows is brilliantly disorienting because when combined with an earlier establishing shot that places the two men on a sort of parapet:

The high angle perspective makes it look like Grisby is falling off the edge of the frame to his death when he says “so long, fella!” and suddenly steps away:

This impression is compounded by the fact that the next scene includes an image of Elsa looking ghostlike as she runs in front of a nighttime cityscape in a white dress:

To the point that it’s strange to hear her and Michael talk about Grisby in the present tense. Equally unforgettable is their later meeting in the Steinhart Aquarium, which Brian Darr called “its most striking location shoot” in an article for SFGate, that features them talking in silhouette as sea creatures of symbolic import swim by:

And a moray eel enlarged to monstrous proportions which reminds me of the one at the National Aquarium in Baltimore we visited every snow day when we lived there:

I also love the shots of Elsa stabbing at buttons on an intercom which appear to cause a man who has been shot to burst through a door in another room:

And a car carrying Michael and Grisby to accelerate and collide with the truck in front of it:

Finally, as American Cinematographer amusingly noted, “the climax of the picture, during which the antagonists shoot it out in this mirrored room, is one of those unforgettable cinematic moments that seem to occur all too rarely these days.”

The joke is that those words were written in 1948, not tweeted out yesterday! Sure, the Crazy House sequence that precedes this one, which Welles told Bogdanovich would have been even more acclaimed had it remained intact, is reduced to just 90 seconds of shadows, signs, and slides:

But a little bit of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (which according to Simon Callow’s biography Welles screened for his cast and crew) goes a long way.

And in the end Naremore concludes that “there is a sense in which all of Columbia’s tampering with the film has not been as disruptive as, say, RKO’s revisions of The Magnificent Ambersons.” To him this is primarily because it is “characterized by a sort of inspired silliness, a grotesquely comic stylization that has moved beyond expressionism toward absurdity.” This certainly is true of Glenn Anders’s performance, which Bogdanovich describes as “free in its eccentricity and eccentric in its freedom.”

I think it’s also because as Robert B. Pippin observes in his book Fatalism in American Film Noir, “Michael plans to be a novelist” and “what we are hearing as the voiceover appears to be the novel he has written after all these events are over,” so the inconsistencies can all be chalked up as bad writing or the sins of an unreliable narrator.

Last but not least Barbara Leaming notes in her biography of Welles that he “read and assimilated [Bertolt] Brecht” shortly before The Lady from Shanghai in preparation for a collaboration that never came to fruition, which to her “explains the peculiar presence of the otherwise incongruous (and hitherto mysterious) Chinese theater sequence toward the end.” Although the translations of the film’s unsubtitled Cantonese dialogue that Kelly Oliver and Benigno Trigo provide in their book Noir Anxiety demonstrate that these scenes are thematically consonant (the opera “performs the trial of a woman accused of being a sinner”) with the rest of the work, her observations that this is also the reason no one in the audience seems bothered by Michael and Elsa talking since “the alienated acting of the Chinese theater is perfectly tolerant of interruptions and disturbances” and that “Brecht writes that the Chinese actor occasionally looks directly at the audience, even as he continues his performance–and so it is in this sequence when the police arrive” remain valid:

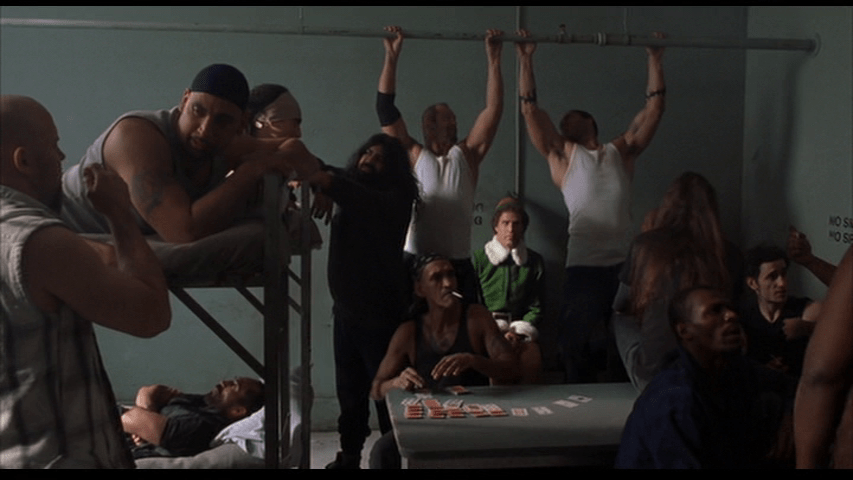

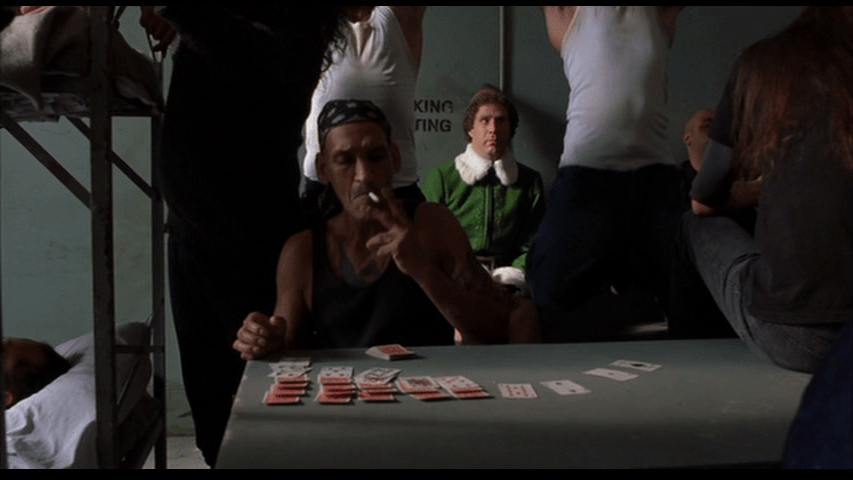

As does her suggestion that “the Chinese theater sequence illuminates the distinctly odd–almost chilly–acting style that permeates the film as a whole.” So, yeah, The Lady from Shanghai is an odd duck of a film! But here’s something even crazier: it also appears to be an inspiration for my December, 2022 Drink & a Movie selection Elf! Compare this shot of two people blatantly flaunting smoking regulations:

With this one:

Which, okay, you’re not convinced. I get it. But consider as well this description of Michael from Joseph McBride’s Welles biography:

Part of what makes Welles’s film so unsettling is the ironic tension between the moral issues and the characters’ apparent lack of interest in them. K.’s whole life in The Trial is changed by his investigation into the principles behind his case, and Quinlan in Touch of Evil spends most of his time rectifying the moral inadequacy of the law; but in The Lady from Shanghai O’Hara treats his legal predicament as only an unpleasant adventure he must get through so he can move on to a more important concern–Elsa Bannister, the lawyer’s wife. Unfortunately, as he discovers, she is the instigator of the whole complex murder plot, and the issues encroach heavily on his fate despite his avoidance of them. At the end he has been forced to formulate a philosophical position similar to the tragic understanding Welles’s other heroes achieve, but of a less definitive nature.

Doesn’t that sound a lot like the exact inverse of the way the contagious goodness of a certain “deranged elf-man” we all know and love teaches a cynical world how to believe again? Something to ponder while you enjoy your drink!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.