Thanksgiving dinner was one of the first meals I ever taught myself to cook. My roommates and I moved off campus prior to our sophomore year at the University of Pittsburgh, and to our delight we learned that we could earn a free turkey by accruing points when we did our grocery shopping at the local Giant Eagle. Thus was born an annual “Friendsgiving” tradition which became my earliest foray into wine pairing when I turned 21. Having no real idea what I was looking for, it’s little wonder that I gravitated toward the endcaps laden with colorfully-labeled Beaujolais nouveau. Although it’s no longer a fixture on my holiday table, I usually can’t resist the urge to pick up a bottle or two every year for old time’s sake. Most (including this year’s selection, the Clos du Fief Beaujolais-Villages Nouveau La Roche 2024 I purchased from Northside Wine & Spirits) are genuinely enjoyable on their own, but my preferred use for them is in Jim Meehan’s Nouveau Sangaree from The PDT Cocktail Book. Here’s how to make it:

2 ozs. Beaujolais nouveau (Clos du Fief Beaujolais-Villages Nouveau La Roche 2024)

1 1/2 ozs. Bonded apple brandy (Laird’s 10th Generation)

1/2 oz. Sloe gin (Hayman’s)

1/4 oz. Maple syrup

2 dashes Angostura bitters

Stir all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with grated cinnamon.

As Robert Simonson said when writing about this drink for the New York Times, “sloe gin and maple syrup remind you that life should be sweet during the holidays.” The former amplifies the floral and fruity notes of the wine, while the latter creates a creamy texture and combines with the caramel and vanilla flavors of the applejack to linger on the palate. The overall impression is something like a poached pear. Meehan’s recipe specifically calls for “Grade B” maple syrup, but as I mentioned back in August, 2022 that rating no longer exists, so use “Grade A Dark Robust” or just the best stuff you can find. Finally, he employs an apple fan garnish, which probably would announce the presence of the brandy more clearly, but this is a bit fussy for us and we’re happy with just grated cinnamon.

The movie Playtime is a perfect match for this beverage because its centerpiece Royal Garden sequence embodies the celebratory and improvisational nature of the celebrations from my 20s I want to commemorate. They’re also both great fits for the month of December. In the case of the cocktail that’s because it can help use up leftover bottles of wine, while the movie employs a seasonally-appropriate green and red color scheme to great effect. Here’s a picture of my Criterion Collection DVD copy of the latter:

It can also be streamed on the Criterion Channel with a subscription and rented from a variety of other platforms, and some people (including current Cornell University faculty, staff, and students) may have access to it through Kanopy via a license paid for by their local academic or public library as well.

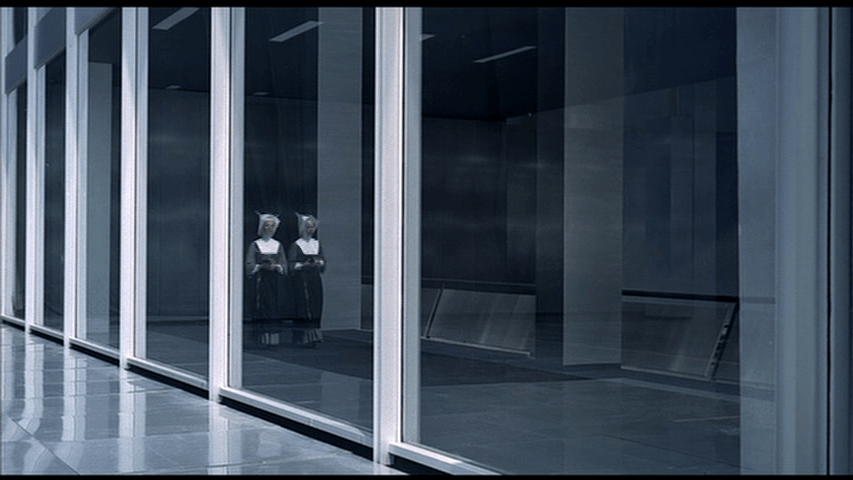

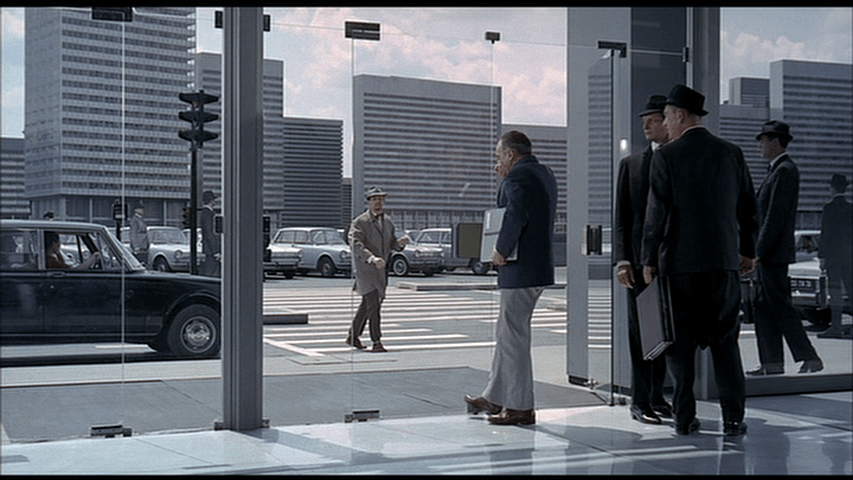

Playtime begins in a place that My Loving Wife, watching it for the first time, assumed was some sort of anteroom to the afterlife, a reading that I imagine director Jacques Tati would have loved. An opening credits sequence featuring clouds, which ties it to some of my other favorite movies, gives way to an establishing shot of a glass and steel skyscraper:

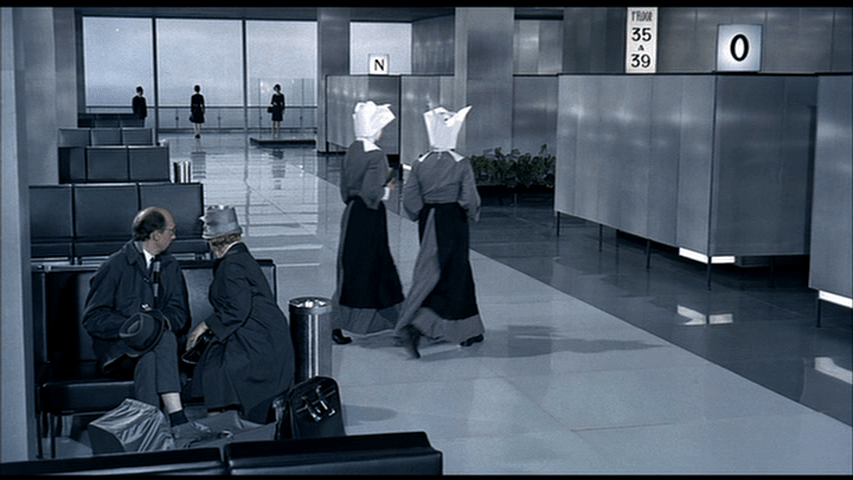

The first human beings we see are two nuns:

And a cut on motion sets up the film’s first gag. Two people, a man and a woman, talk in the foreground.

We can tell from their conversation that he’s going somewhere: “wrap your scarf around so you don’t catch cold,” his companion tells him, and “take care of yourself.” They also talk about the other people who appear in the frame with them, including first a man who “looks important” and then “an officer”:

It’s only when a woman who looks like she could be a nurse carrying a bundle of towels that resemble an infant in swaddling clothes appears accompanied by the sound of a baby crying that we notice the gray stroller in front of them which up until this point had completely blended into its surroundings:

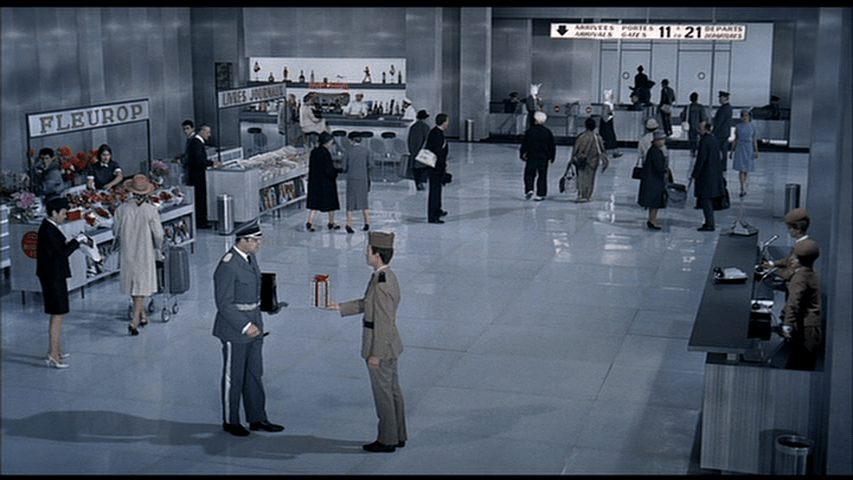

This is just the first of many instances of what Lucy Fischer (who was chair of the film studies department at Pitt when I was a student there) calls “one of the major functions of Tati’s remarkable soundtracks” in a Sight & Sound article called “‘Beyond Freedom & Dignity’: An Analysis of Jacques Tati’s Playtime“–the way they “provide aural cues to guide our visual perception.” As Fischer notes, he uses color the same way, beginning with the elaborate presentation of a gift which we pick out from a crowded monochrome mise-en-scène in large part because of its bright red bow:

It’s also an early example of what Lisa Landrum identifies as Tati’s use of color to “symbolically to reveal narrative and allegorical meaning” in her chapter in the book Filming the City, here as a “crimson reminders of life’s more sensual pleasures.”

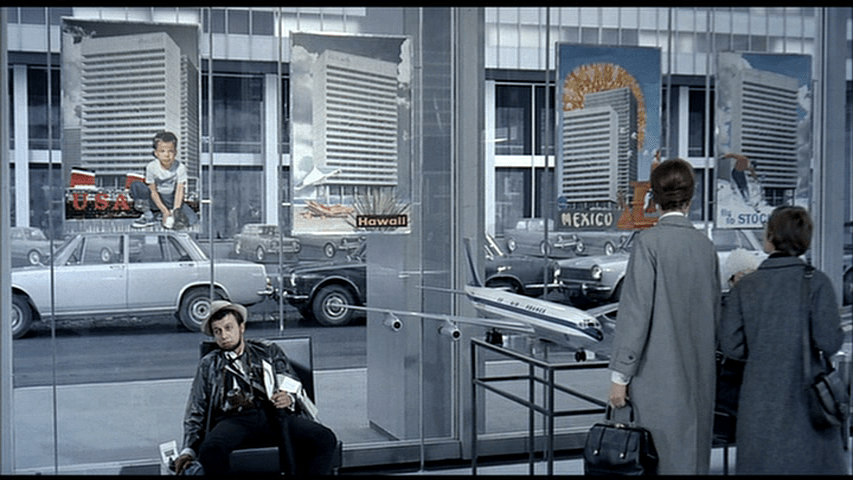

We next encounter a gaggle of American tourists who will eventually lead us out of what by now we realize is an airport:

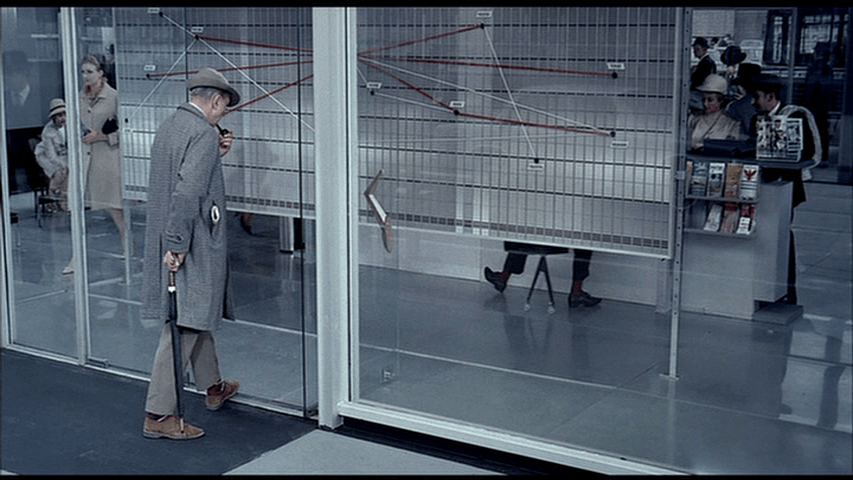

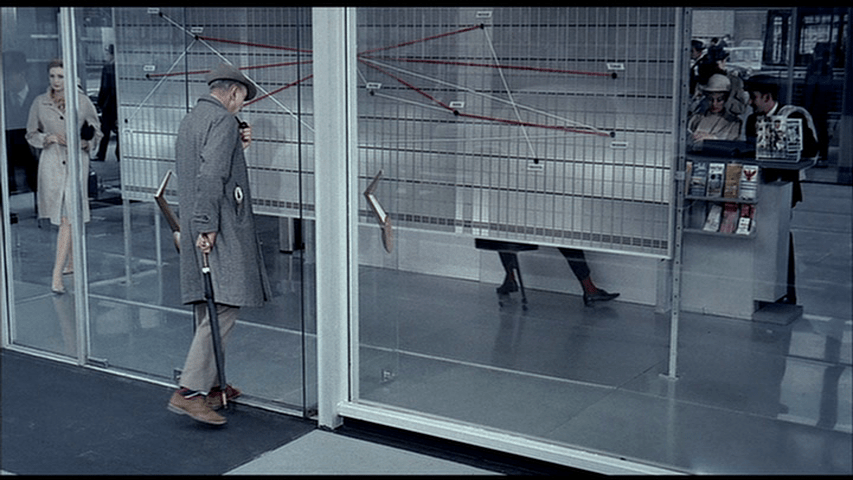

Followed by the introductory appearance of our ostensible protagonist Monsieur Hulot (Tati) with his signature hat, overcoat, and umbrella in the background of the same scene:

And the inaugural example of what Jonathan Rosenbaum refers to as “‘false’ Hulots” a few moments later:

It’s unclear (and completely irrelevant) what Hulot is doing at the airport, but we next encounter him making his way to an appointment in another modern high-rise, where he is announced via the most over-engineered intercom system on this side of Toontown:

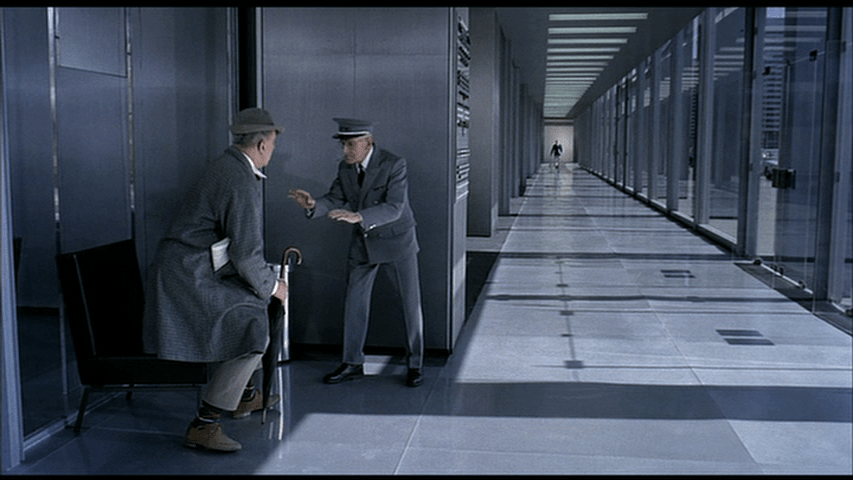

We hear the footsteps of the man he’s there to meet, Monsieur Giffard (Georges Montant), before we see him approaching down a deep focus corridor so long that the doorman (Léon Doyen) tells Hulot to sit back down twice:

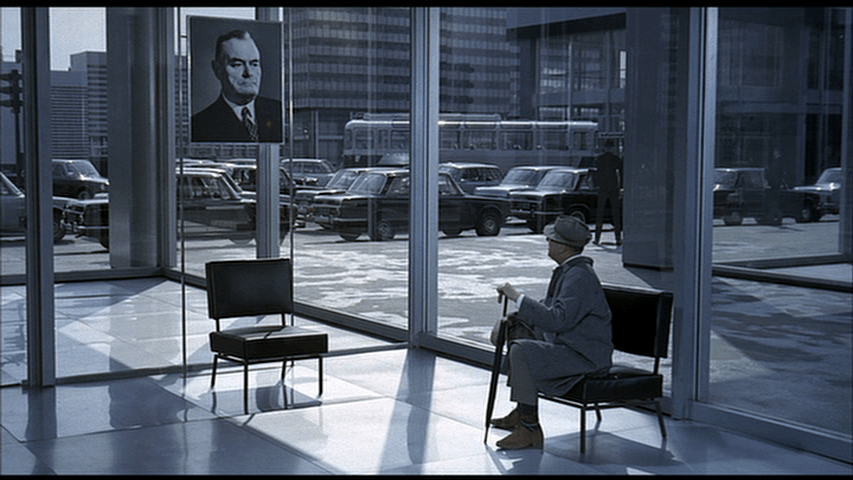

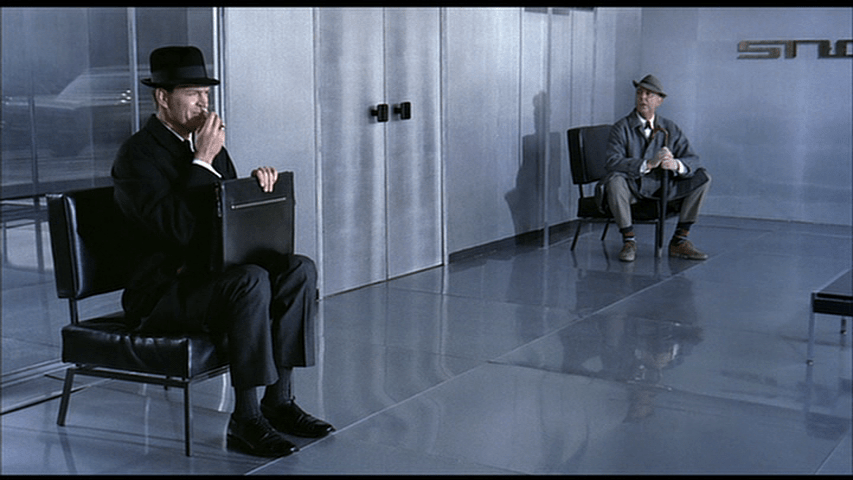

When Giffard finally arrives, he ushers Hulot into a display case-like waiting room filled with portraits that seem to disapprovingly watch his every move:

A man with fascinatingly robotic habits that seem to mark him as a natural inhabitant of this sterile environment:

And a slippery floor that causes what Rosenbaum describes as “the first significant curve in the film that undermines all the straight lines and right angles dictated by the architecture and echoed by all the human movements”:

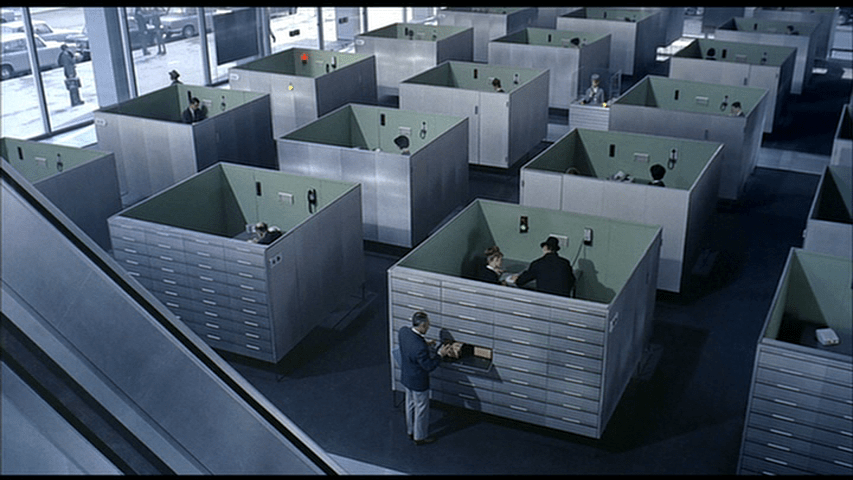

Giffard and Hulot wind up chasing each other through a maze of cubicles in which a receptionist’s rotating chair creates the impression of turning a corner and getting nowhere:

Green (bottom right of frame) and red lights (top left) draw our attention to two people who don’t realize they’re standing right next to each other talking on the phone:

And Giffard’s reflection results in them losing each other for good when Hulot leaves the building they’re both in for the identical one next door:

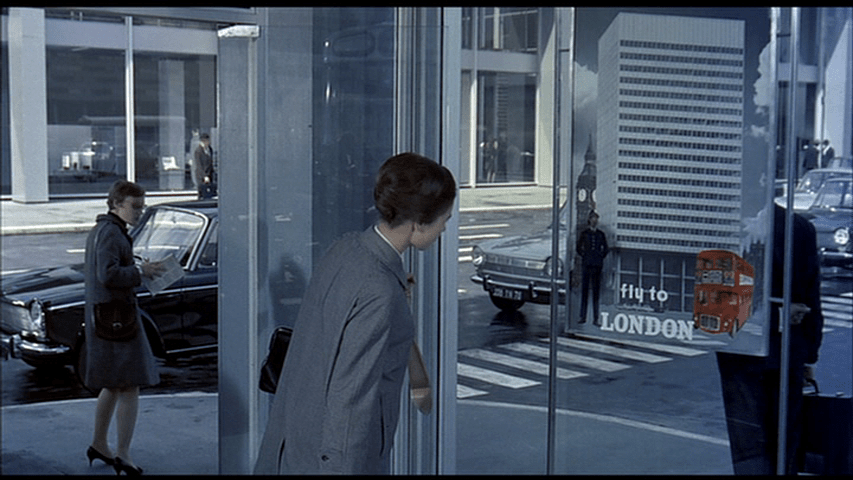

The next 20 minutes or so of the film unfold during a business exposition that both Hulot and the Americans from the airport find themselves attending, him by accident and them on purpose. One tourist named Barbara (Barbara Dennek) pursues an illusive “real Paris” that she’s only able to glimpse in reflections while her companions ooh and aah over a broom with headlights:

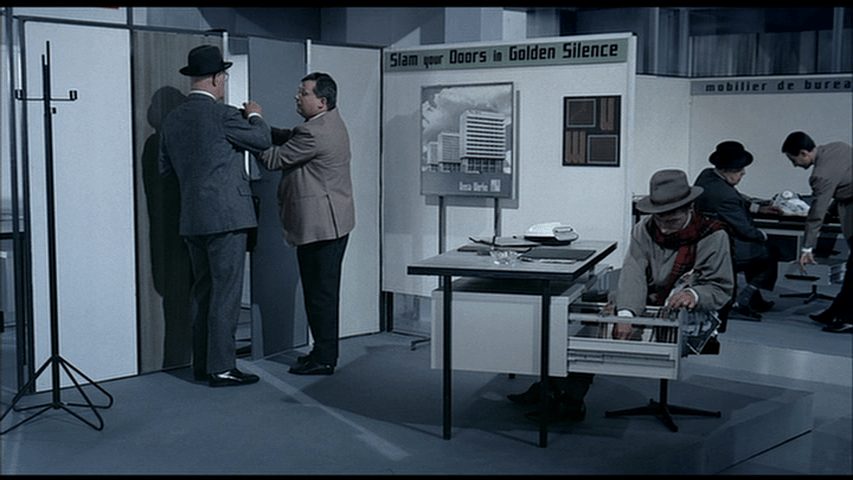

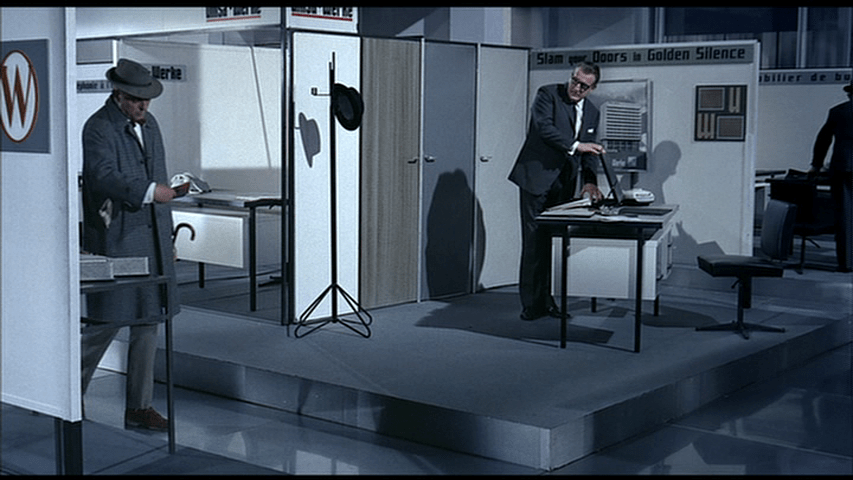

Meanwhile, Hulot is mistaken (due to confusion with another false Hulot) for first a corporate spy by a German businessman whose company’s motto is “Slam your Doors in Golden Silence,” then a lamp salesman when he loses his trademark outerwear:

The sequence ends with Tati making his critique of the sameness of contemporary architecture more explicit via a set of travel agency posters:

Hulot watching the appearance of a disembodied pair of dancing feet created by a busy travel agent on a stool with wheels when viewed from behind:

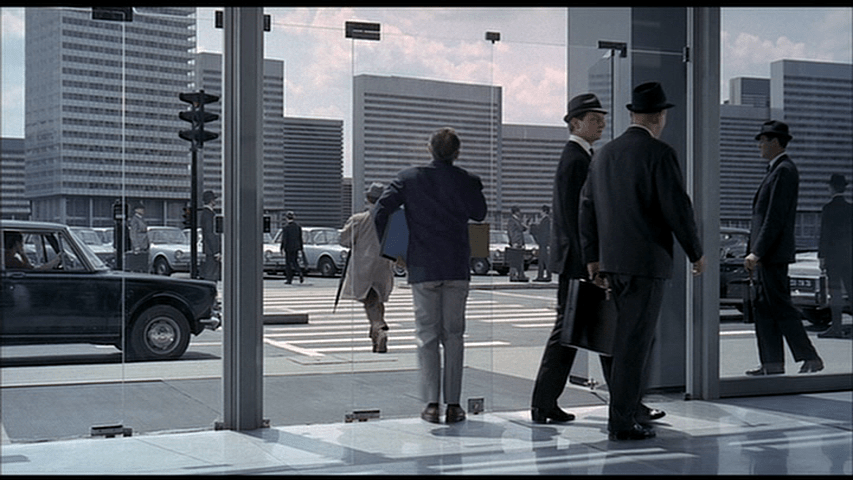

And Giffard bumping his nose when he attempts to wave down yet another false Hulot through yet another pane of glass:

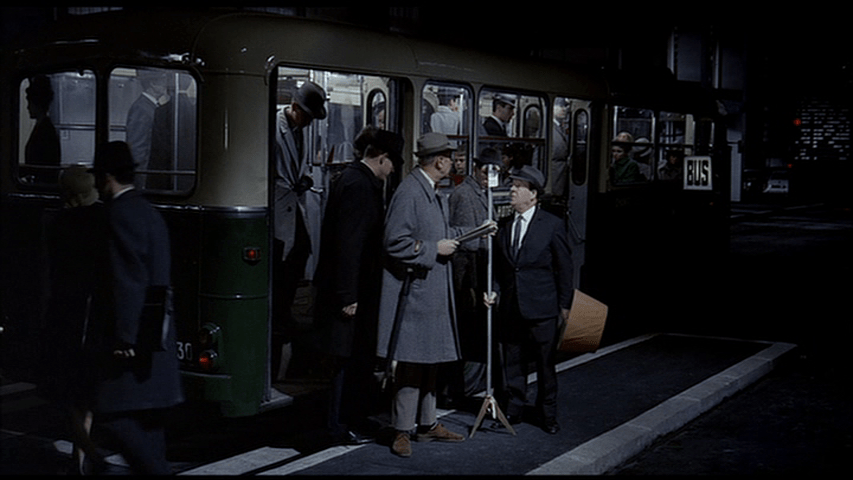

The gap to the three set pieces that are the reason Playtime rates as one of cinema’s all-time great comedies in my book is bridged by a transition featuring a nice bit of business whereby Hulot holds onto a lamp thinking it’s part of the bus he’s riding:

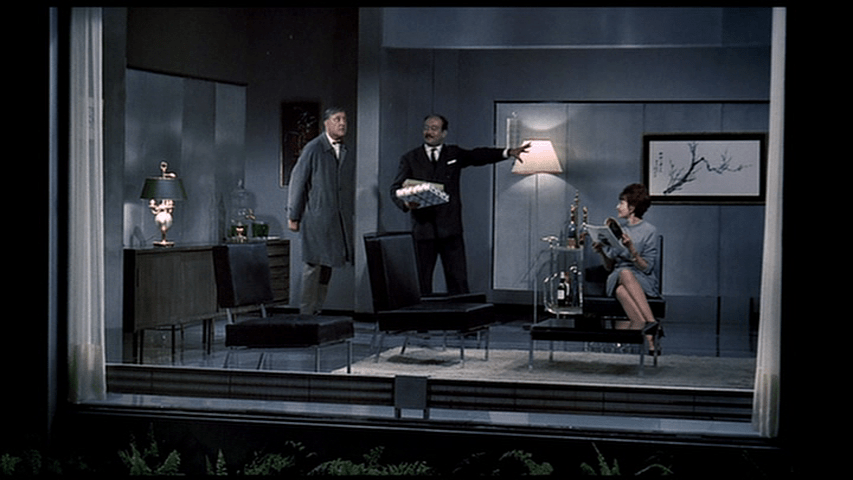

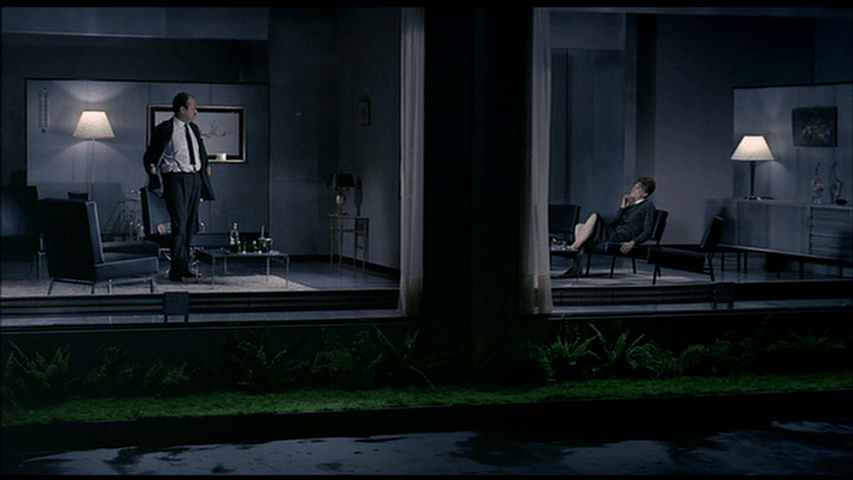

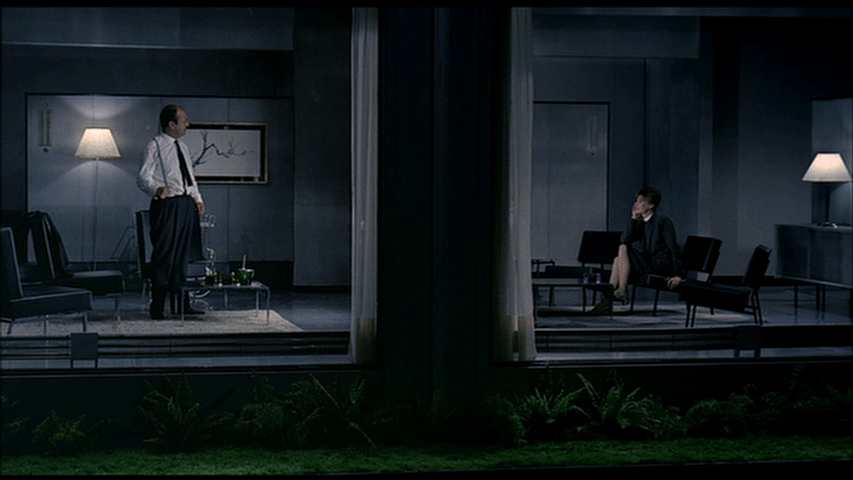

As soon as he disembarks, he is hailed by an old army buddy named Schneider (Yves Barsacq) who invites him to the apartment that inspired this month’s drink photo:

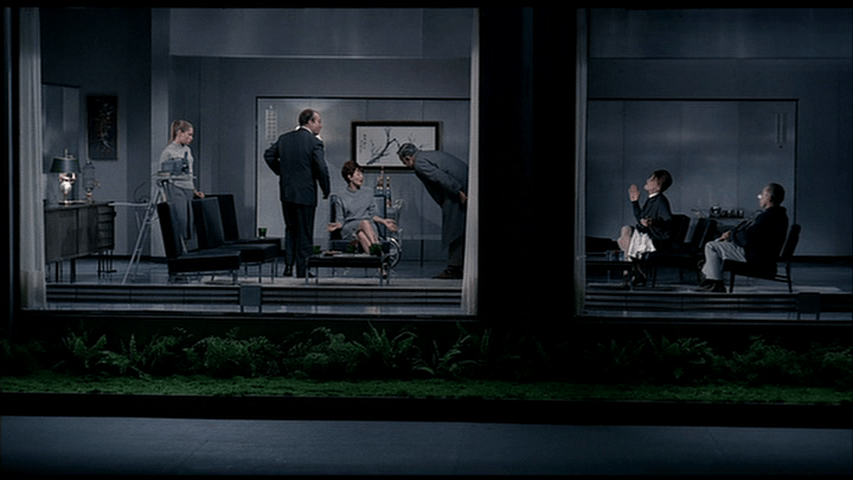

We view everything that transpires over the subsequent ten minutes from this same outside view, and when the camera pulls back to also show the neighbors’ living room as well, characters who can’t really see each other seem to be interacting. The apartment next door turns out to belong to Giffard, and the Schneiders and Hulot appear to stare in surprise when he comes inside with a bandaged nose:

The sequence also includes what look to us like offended reactions to rude gestures:

And, best of all, a striptease:

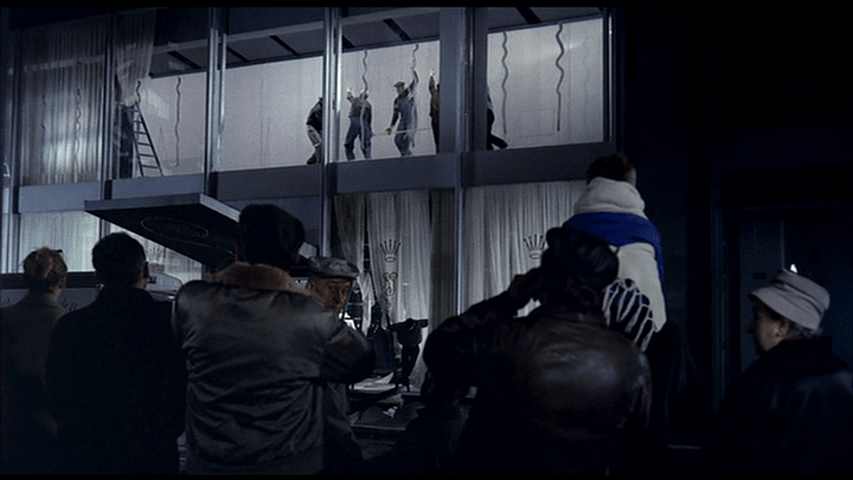

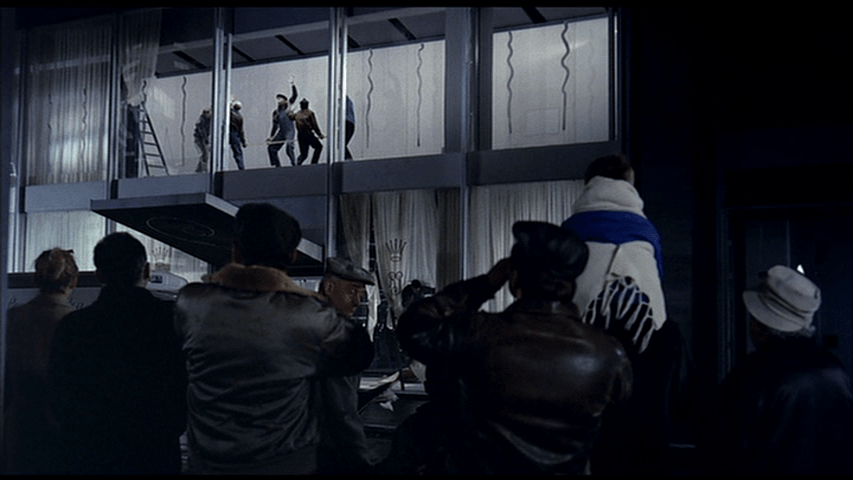

After departing, Hulot finally meets up with Giffard in a crowd of bystanders watching some construction workers who look like they’re performing a vaudeville routine:

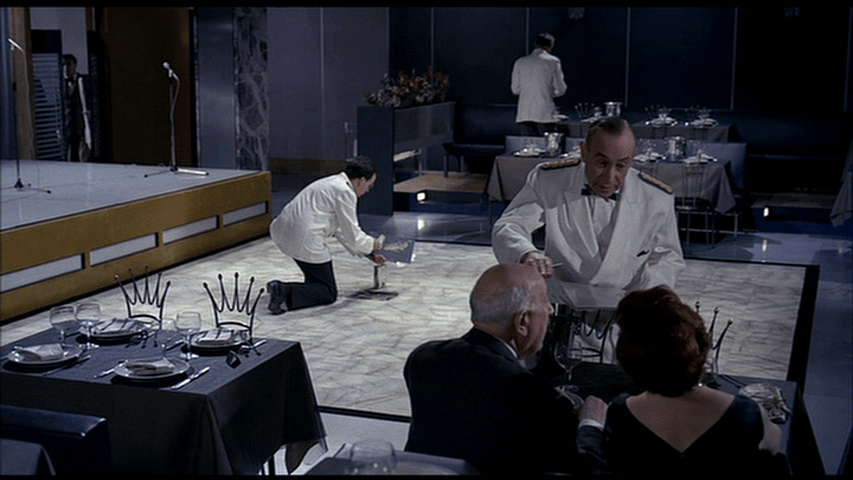

Before finding himself at the soft opening of an establishment called the Royal Garden at the invitation of the doorman (Tony Andal), another friend from his military days. Of course, this tour-de-force, nearly hour-long sequence has been going on for twenty minutes by the time he arrives, which is about par for the course according to Malcom Turvey, who calculates in his book Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism that Hulot is on screen less than 50% of the movie up to this point. I’d need a whole separate post to do justice to the way the nightclub basically falls apart over the course of a single service to the delight of its guests, who have more and more fun as the evening spirals further and further out of control, but highlights include a waiter fixing a broken tile in the background while another pantomimes saucing a fish in the foreground using the exact same motions:

Barbara and her companions arriving to complaints from the locals that they’re “so tourist,” but also admiring comments about how chic her outfit is, which solidifies a theme running throughout the film that there’s actually very little we can do to control how other see us and that this is neither inherently positive or negative:

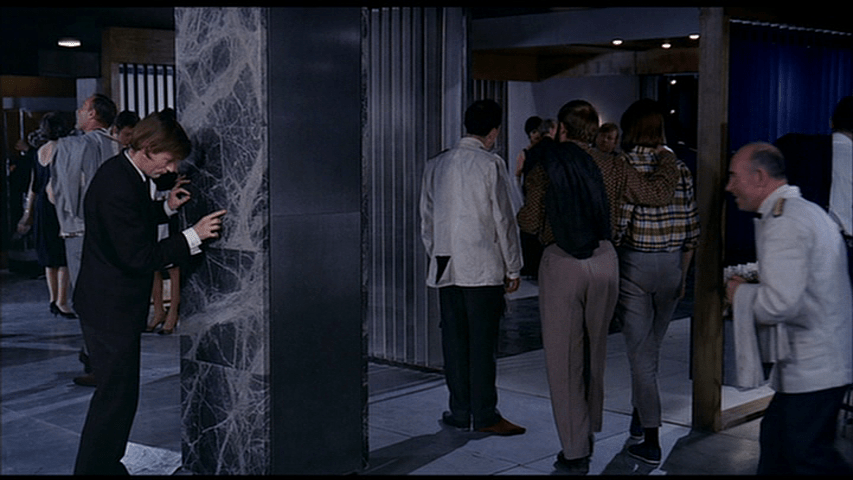

Hulot’s friend letting people in and out of a mobile invisible door after Hulot walks into it and shatters the glass:

A ceiling that comes tumbling down when Hulot leaps for a golden apple decoration at the behest of a wealthy customer named Schultz (Billy Kearns), whose nationality Turvey finds significant because “it is Americans and American culture that disrupt the homogeneity of the modern environment, thereby allowing for the carnivalesque, utopian moments of communal enjoyment,” and which further ties the movie to the drink I’m pairing it with via the Laird’s:

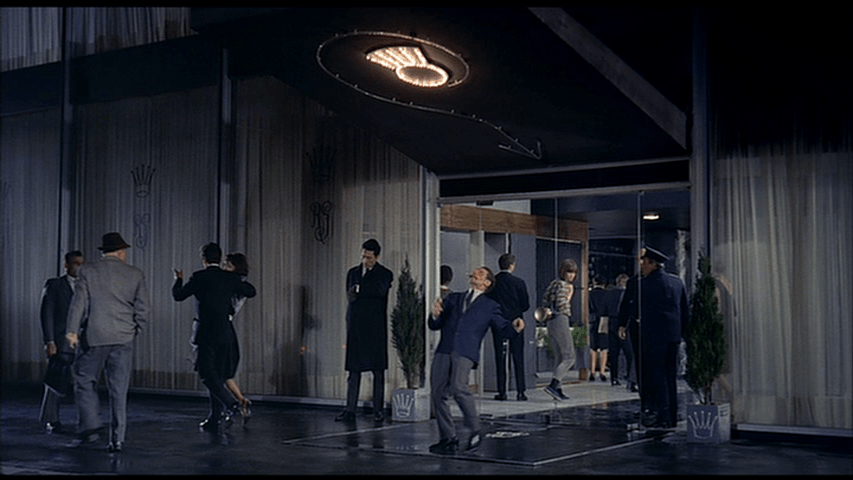

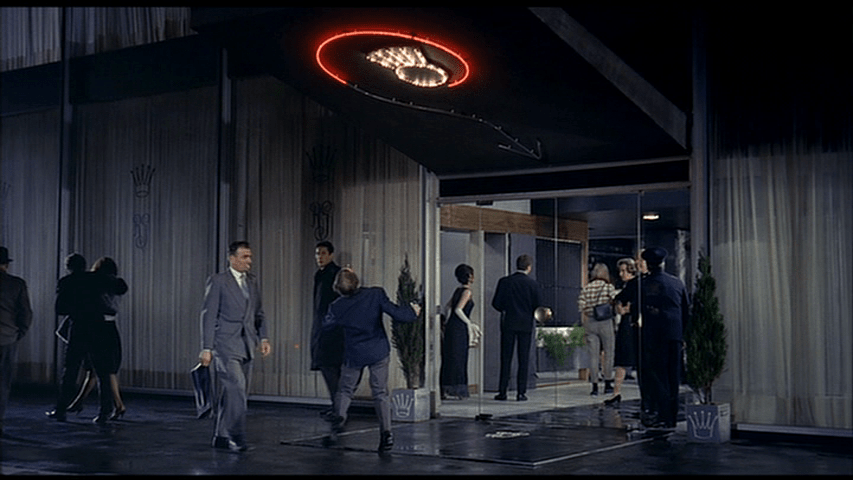

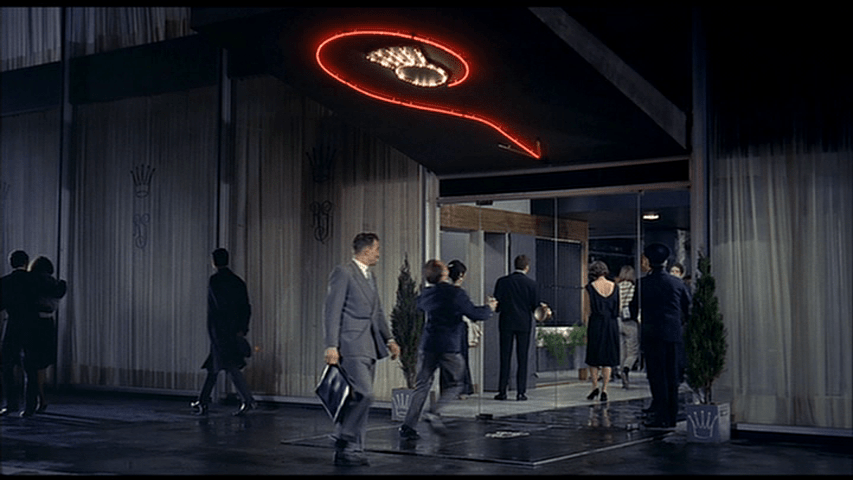

A drunk who has just been kicked out of the Royal Garden following its neon arrow sign back inside:

Flowers that look like they’re being watered with champagne:

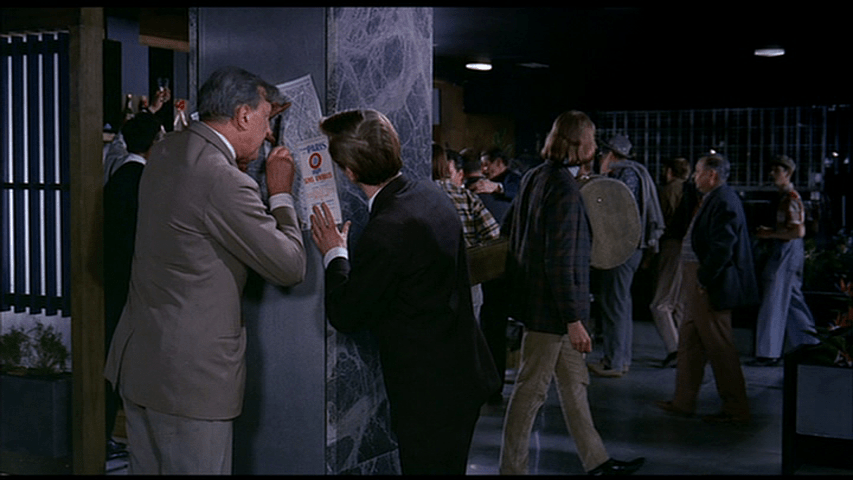

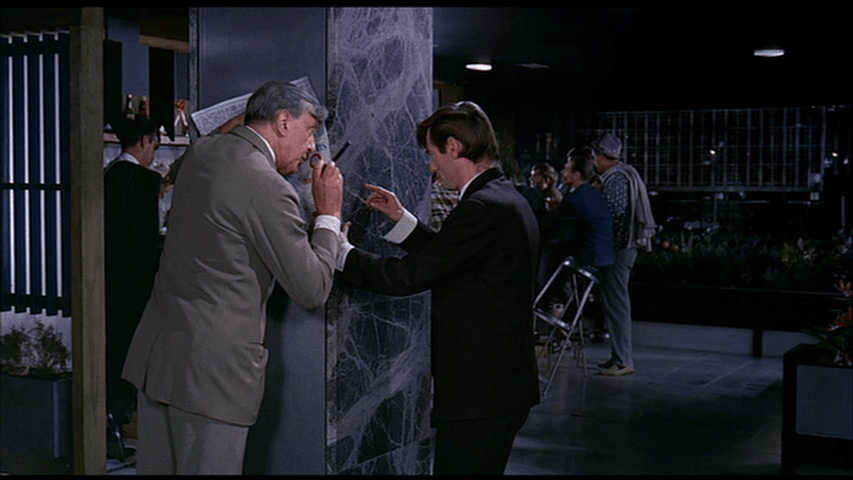

And another drunk confusing the lines on a marble pillar for a map:

But for all the joyful anarchy of this scene, my favorite part of Playtime is definitely its ending. As Barbara and her tour group make their way back to the airport the following morning, Paris transforms into a carnival, complete with a traffic circle carousel that stops and restarts when a man puts a coin in a parking meter:

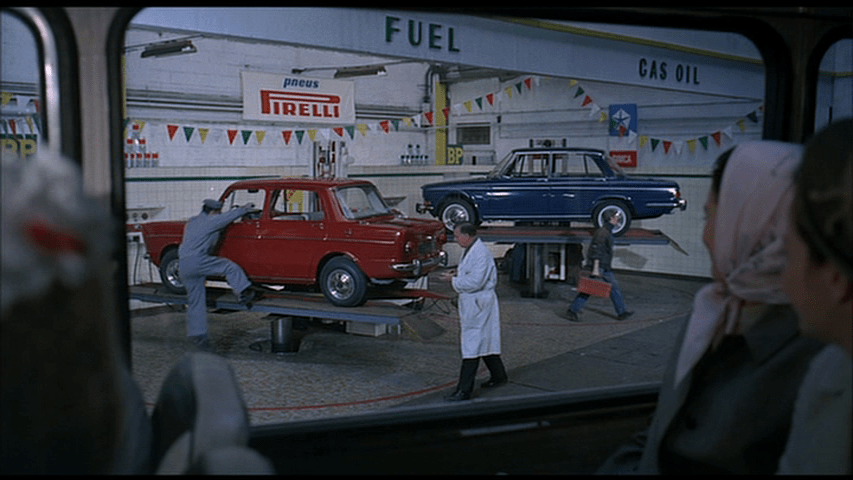

A hydraulic lift ride:

A vertiginous effect created by a tilted window:

And streetlights that will now forever remind you of lilies of the valley thanks to a thoughtful parting gift that Hulot gives Barbara:

As Sheila O’Malley writes in a blog post about the movie, “if urban alienation is portrayed in Playtime (and it is), it is portrayed in a way that is distinctly absurdist, turning the mundane into the surreal. It does not bemoan the fate of modern man, it does not say, ‘Oh, look at how we are all cogs in a giant wheel, and isn’t it so sad?’ It says, ‘Look at how we behave. Look at how insane it is. We need to notice how insane it is, because it’s hilarious.’” While you absolutely can read the film as a critique of what automation and commercialism have done to the world of the 1960s and today, I prefer to treat it the same way O’Malley does, as a how to guide to finding pleasure in it: keep your eyes open, use your imagination, and don’t take yourself to seriously. Which is pretty good advice for stress-free hosting and family dinners, too, so: happy holidays!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.