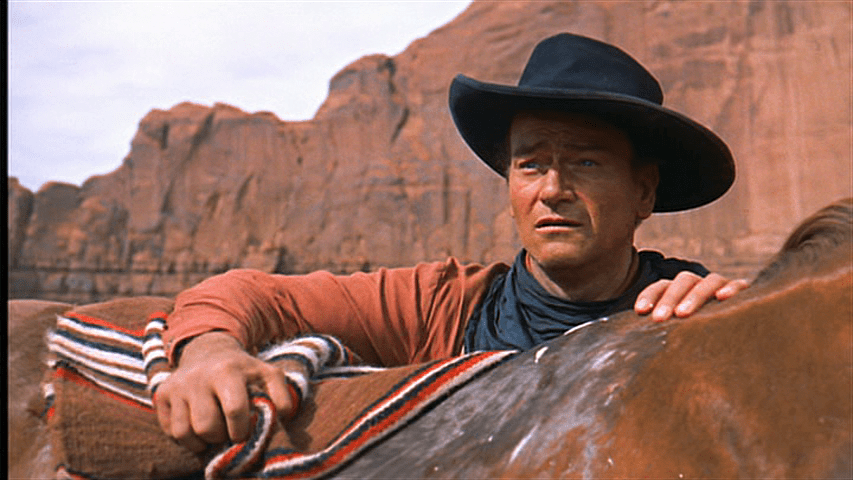

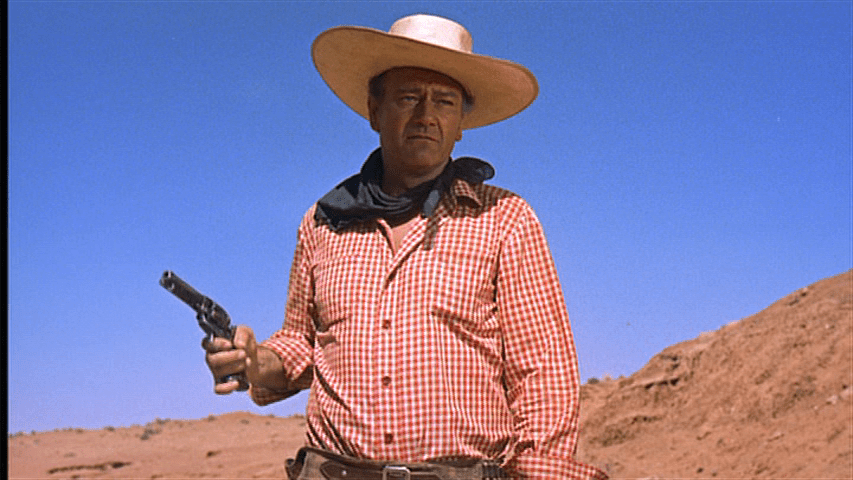

USS Richmond Punch was a big hit when I made it for Thanksgiving a few years ago. It’s on the menu again this year, so I definitely wanted feature it in this month’s Drink & a Movie post. When thinking about what film to pair it with, the name immediately made me think of one of cinema’s great antiheroes, unapologetic former Confederate soldier Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) from The Searchers. Interestingly, David Wondrich identifies the recipe as originating during the Civil War era, which means it theoretically could be the concoction in this punch bowl:

The way we make it combines elements from the article linked to above and the recipe in Wondrich’s book Punch: The Delights (and Dangers) of the Flowing Bowl:

6 lemons

1 1/2 cups caster sugar

2 cups black tea

2 cups Jamaican rum (Smith & Cross)

2 cups cognac (Pierre Ferrand 1840)

2 cups ruby port (Graham’s Six Grapes)

4 ozs. Grand Marnier

2 750 ml bottles sparkling wine (Roederer Estate Brut)

Prepare an oleo-saccharum by removing the peels from the lemon, trying to get as little of the pith as possible, and muddling them with the sugar. Set aside for at least an hour. Meanwhile, juice the lemons and make the tea by pouring 16 ounces of hot (but not boiling) water over two tea bags and steeping for exactly five minutes. Add the lemon juice and tea to the oleo-saccharum and strain into a gallon container. Add the spirits and refrigerate overnight. When ready to serve, add to a punch bowl with a block of ice and the sparkling wine. Garnish with lemon slices and grated nutmeg.

As a special occasion beverage, this is definitely a time to break out your favorite spirits, which is why we go with Smith & Cross, Pierre Ferrand 1840 Original Formula, and Roederer Estate Brut. We are a family of tea drinkers and that flavor is prominent here, which is one of the main reasons we love this punch, which is sweet and tart and just a bit effervescent. It does pack a wallop, though, and the tannins on the finish will make you want to take another sip and then another, so handle with care! Or, you know, just be sure to snack liberally while you imbibe.

The screengrabs in this post are from my Warner Home Video DVD copy of the film, which is still going strong after 25 years:

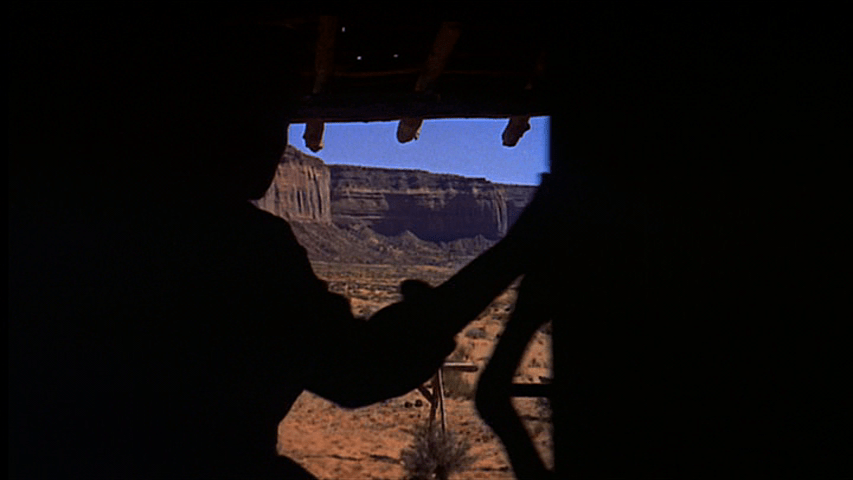

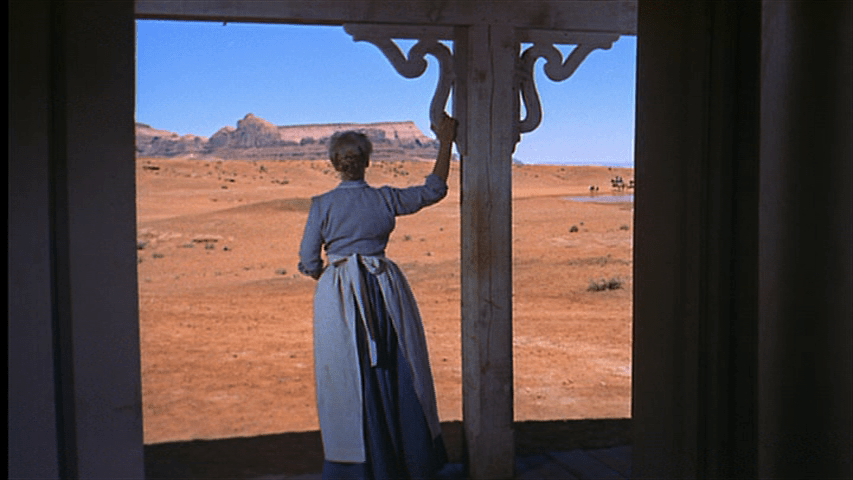

It can also be rented from a number of streaming video platforms. The Searchers is hardly immune from the sins of representation which plague many classic westerns: see, for instance, Tom Grayson Colonnese’s observation in the collection of essays on the film edited by Arthur Eckstein and Peter Lehman that allowing the Navajo extras who play Comanches to speak their own language is as discordant “as if when we meet the Jorgensens, they have Italian accents, or as if the Hispanic Comanchero who finally leads the searchers to Scar speaks with a heavy Swedish accent.” Unlike most of them, though, racism is one of its explicit themes. It begins, famously, in “Texas 1868” (as an introductory title card reads) with Dorothy Jordan’s Martha Edwards opening a door:

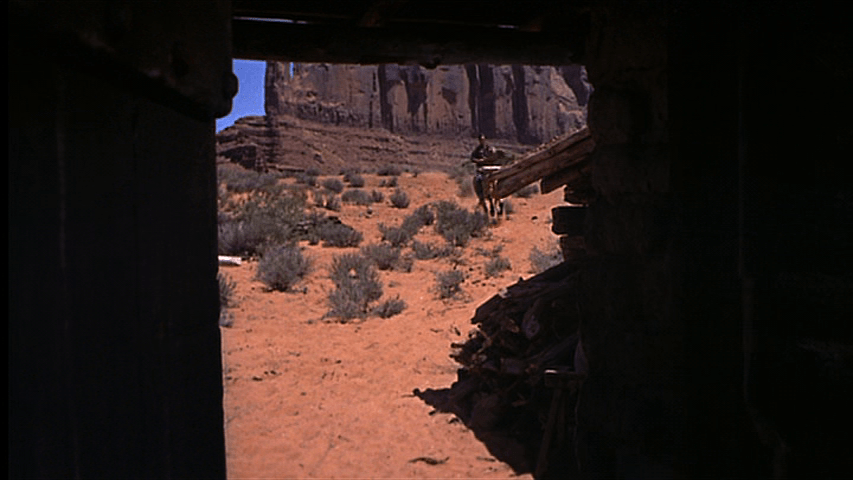

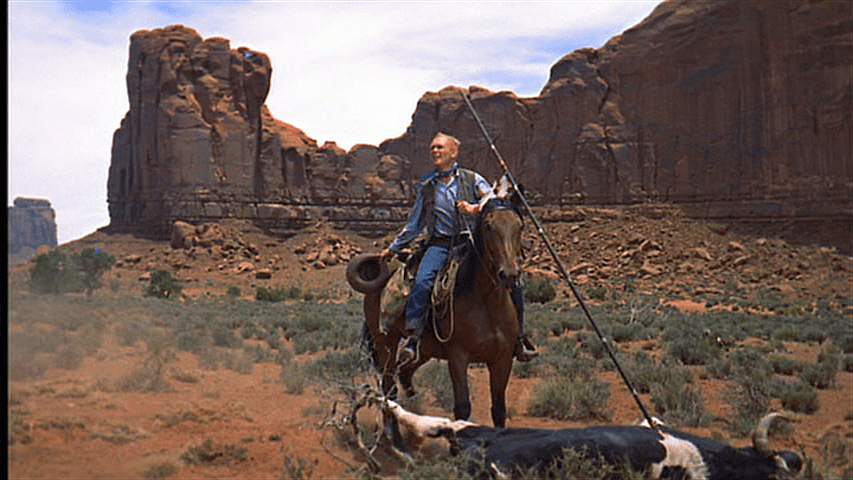

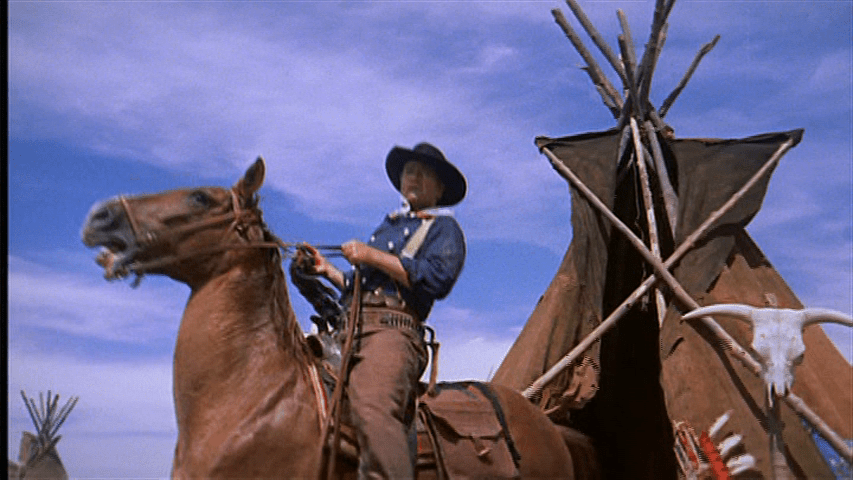

As the camera tracks forward, following her outside, a tiny figure on horseback emerges out of the striking desert landscape:

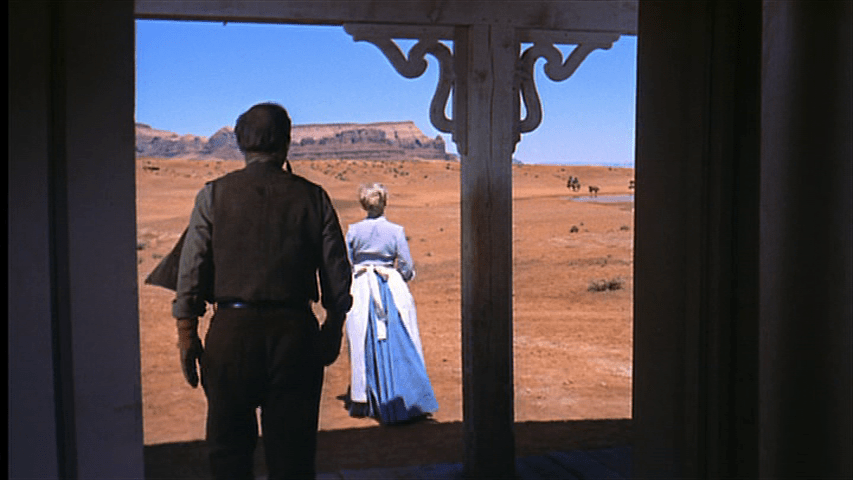

As it draws closer, Martha is joined first by her husband Aaron (Walter Coy):

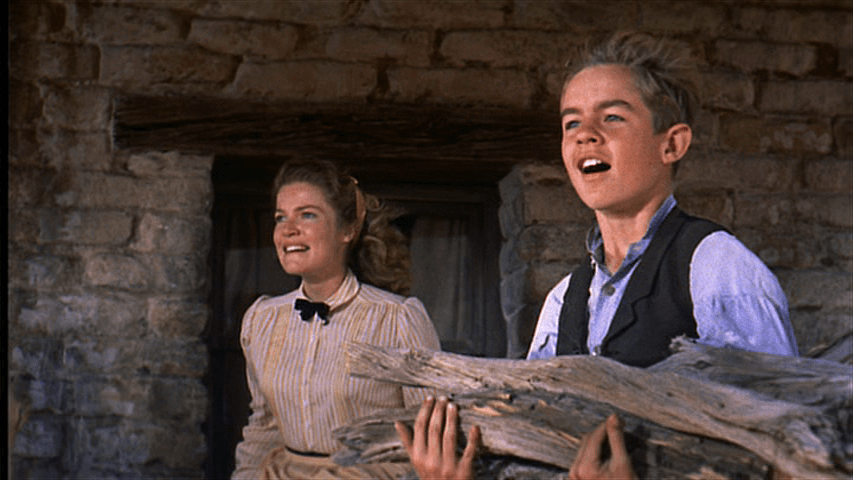

Then their three children. “That’s your Uncle Ethan!” says Pippa Scott’s Lucy to Robert Lyden’s Ben.

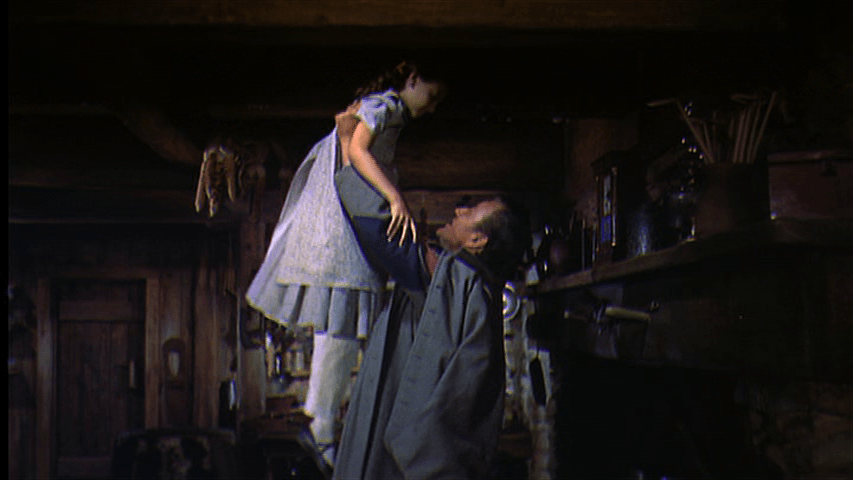

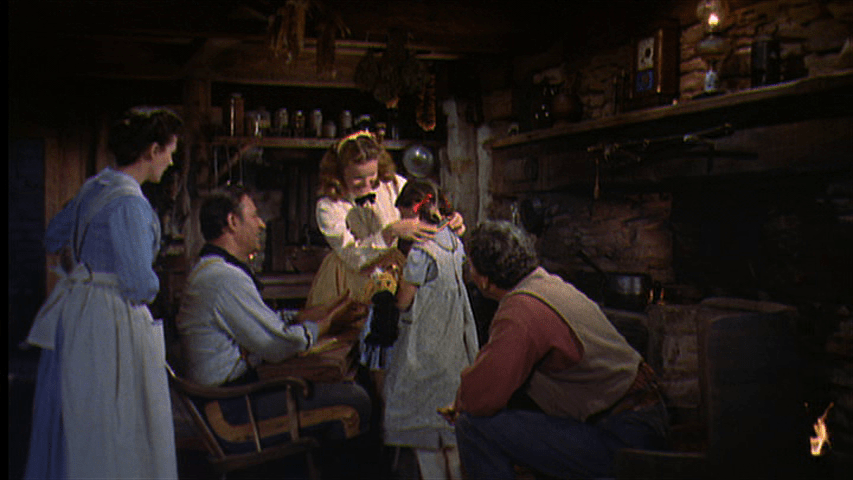

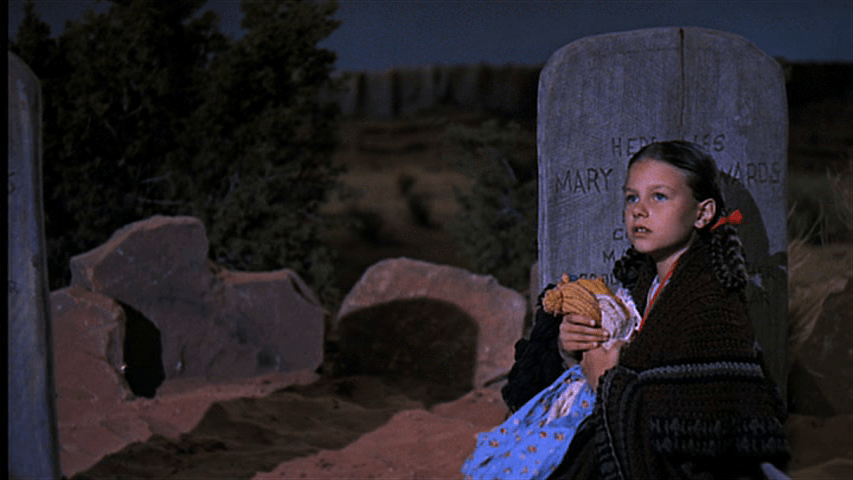

Inside, Ethan lifts his youngest niece Debbie (Lana Wood) to the rafters:

And although he declines to answer Aaron’s question about where he’s been for the past three years, he does specify that it wasn’t California, gazing at Martha the whole while:

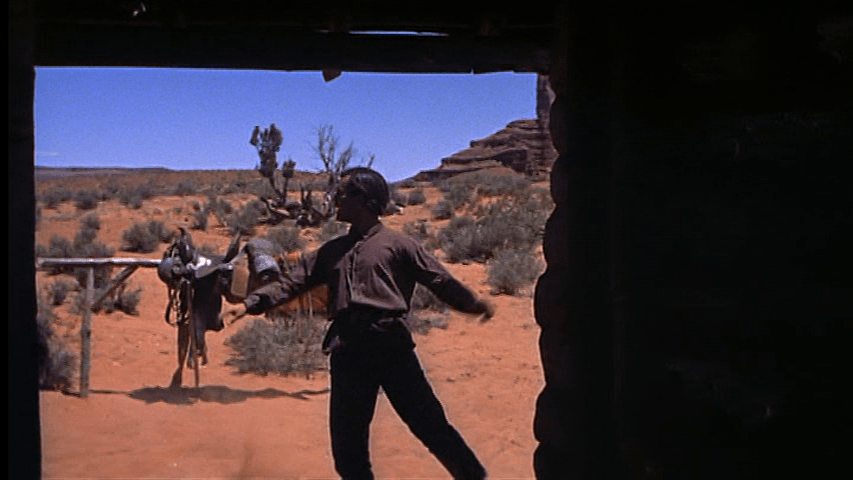

The final member of the family, Jeffrey Hunter’s Martin Pawley, is introduced in the next scene in a variation on Ethan’s entrance:

“Fella could mistake you for a half-breed,” Ethan tells him over dinner.

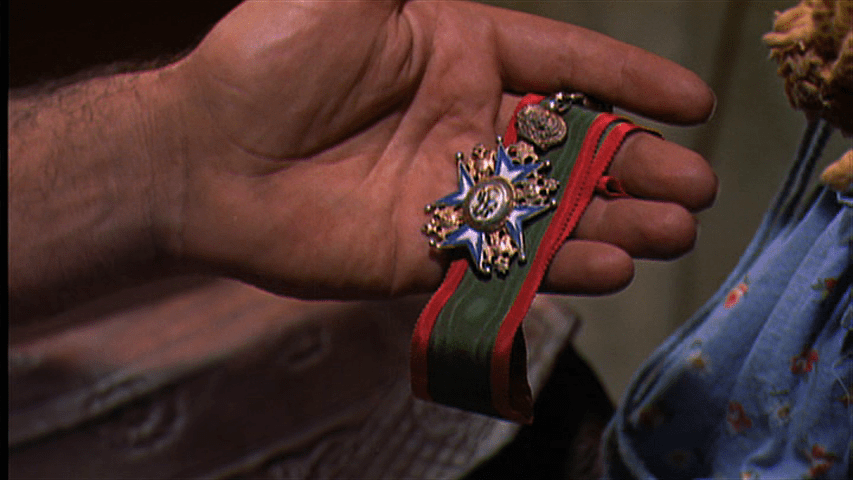

“Not quite: I’m one-eighth Cherokee, and the rest is Welsh and English,” he replies. “At least that’s what they tell me.” You see, “it was Ethan who found you, squalling under a sage clump after your folks had been massacred,” Aaron explains. “It just happened to be me,” Ethan says, “no need to make more of it.” That night before the children to go bed, he makes Debbie a present of what Frank Nugent’s screenplay describes as “something appropriate to Maximilian of Mexico”:

Moments later, he tosses Aaron two bags of double eagles by way of clarifying that he expects to pay his way.

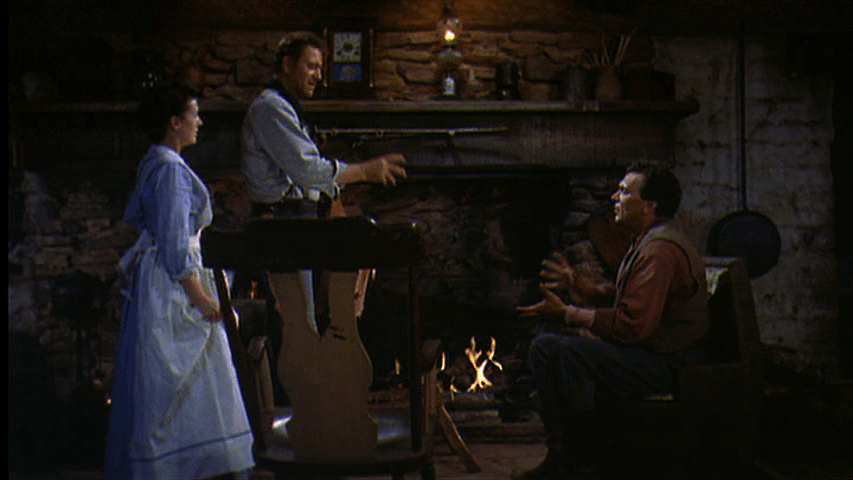

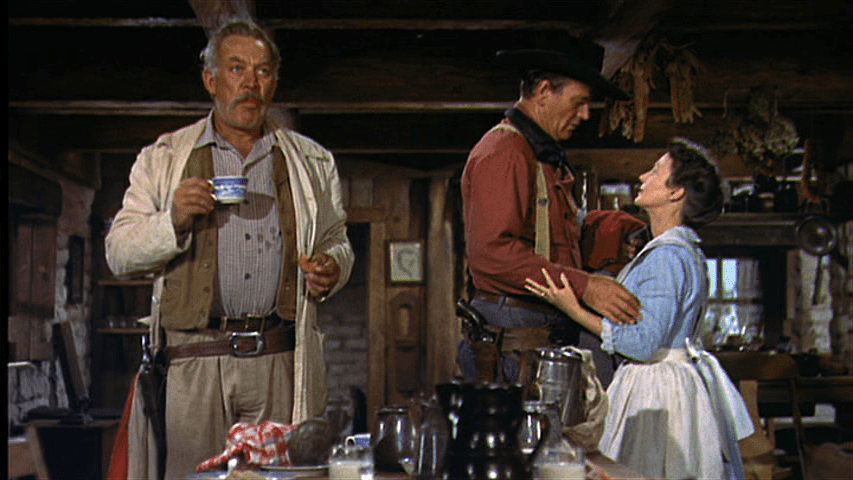

“That’s fresh minted–there ain’t a mark on it!” Aaron observes, to which Ethan simply says, “so?” The next morning breakfast is interrupted by a visit from Ward Bond’s Reverend Captain Samuel Johnson Clayton and his company of Texas Rangers, who are looking for cattle rustlers who they think have run off the herd belonging to Lars Jorgensen (John Qualen), whose son Brad (Harry Carey Jr.) has been “sittin’ up with” Lucy. Their intention is to deputize Aaron and Marty, but Ethan tells his brother to stay close in case the real culprits were Comanche. As they prepare to depart, Clayton chivalrously declines to observe a goodbye which makes it clear that Ethan and Martha are in love with each other:

The posse is 40 miles away when Marty rides up to Ethan to comment that “there’s something mighty fishy about this trail.”

Sure enough, Brad finds his father’s prize bull with a Comanche lance in it.

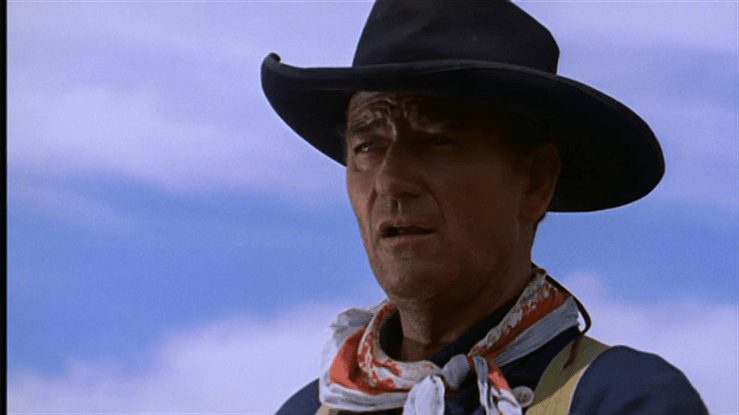

Ethan is the first to realize what it means: “stealing the cattle was just to pull us out. This is a murder raid.” The most likely targets are either the Jorgensen or Edwards places, and the majority of the Rangers ride for the former because it’s closer. Marty immediate heads for home against the advice of Ethan, who observes that their horses need rest and grain. The younger man obviously thinks he’s being callous, but the anguished look on Ethan’s face as he rubs down his horse is anything but:

The attack itself isn’t shown, only the brilliantly tense lead-up to it which features outstanding crepuscular lighting:

A devastating camera movement toward Lucy when she realizes what’s about to happen:

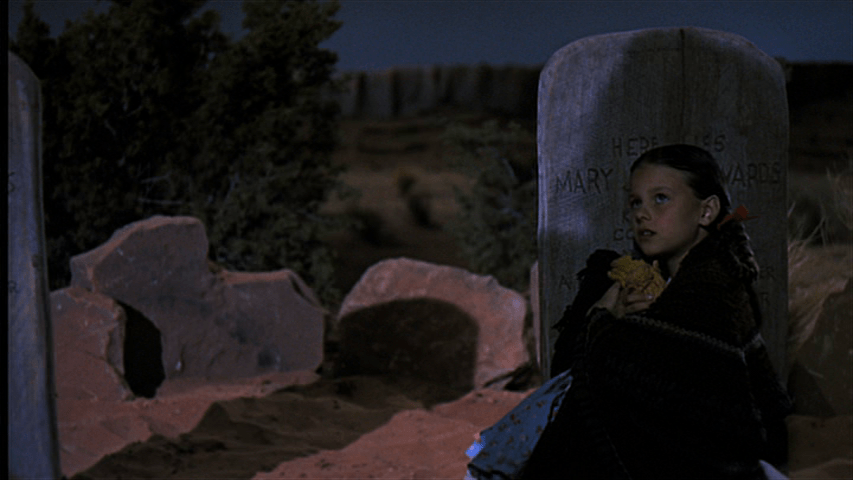

And a terrifying shadow falling over a tombstone that informs us that Ethan and Aaron’s mother was also killed by Comanches:

It ends on a close-up of the Comanche chief Scar, who unfortunately is played by a white man (Henry Brandon), blowing a horn to signal the start of the attack:

Fade to black. Ethan is proven right about the horses when he and Mose Harper (Hank Worden), who stayed behind with him, overtake Marty and ride past him:

But they arrive too late to help. Ethan discovers Martha’s body in another reprise of the film’s opening shot:

Aaron and Ben are also dead, while Debbie and Lucy have been captured. And thus begins the titular search. The same number of men ride out after the girls as went looking for Jorgensen’s cattle earlier, and soon enough they’re following a trail of corpses as warriors Aaron wounded die on the trail. Ethan shoots out the eyes of one, prompting Clayton to ask him, “what good did that do you?”

Mose pantomimes Ethan’s cold reply: “by what you preach, none, but what that Comanche believes, ain’t got no eyes, can’t enter the spirit land and has to wander forever between the winds. You get it, Reverend.”

Sam Girgus writes in his book Hollywood Renaissance: The Cinema of Democracy in the Era of Ford, Capra, and Kazan, “of course, Ethan doesn’t ‘get’ that he really has just described his own life and destiny of wandering over a nightmare landscape that denies ‘the spirit’ and the value and meaning of life,” but I find it significant that his action is prompted by Brad desecrating the body first with a rock:

In fact, not even Ethan’s most extreme racist actions or sentiments expresses are unique to him, which seems to support the statement Joseph McBride and Michael Wilmington make in their monograph on director John Ford that “it is chillingly clear that Ethan’s craziness is only quantitatively different from that of civilization in general.” Anyway, he soon locates the raiders they’re looking for and proposes that they wait until nightfall and then jump them. Clayton decides they’ll try to run off their horses instead. Ethan disagrees, but Clayton says, “that’s an order.” Ethan replies by hurling a canteen at him with the words, “yes sir, but if you’re wrong, don’t ever give me another.”

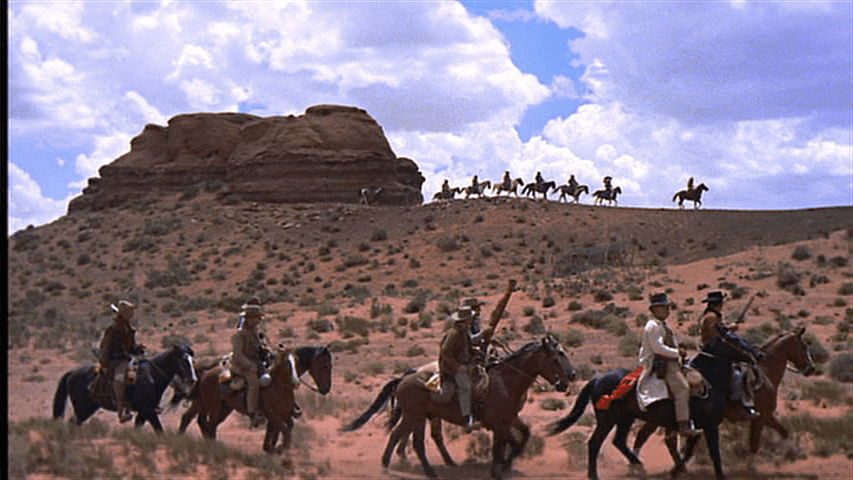

This is followed by another one of the movie’s great set pieces, a frantic ride to a strong defensive position across a river that features lots of great parallel and intersecting lines after Clayton’s plan fails and the posse finds itself surrounded:

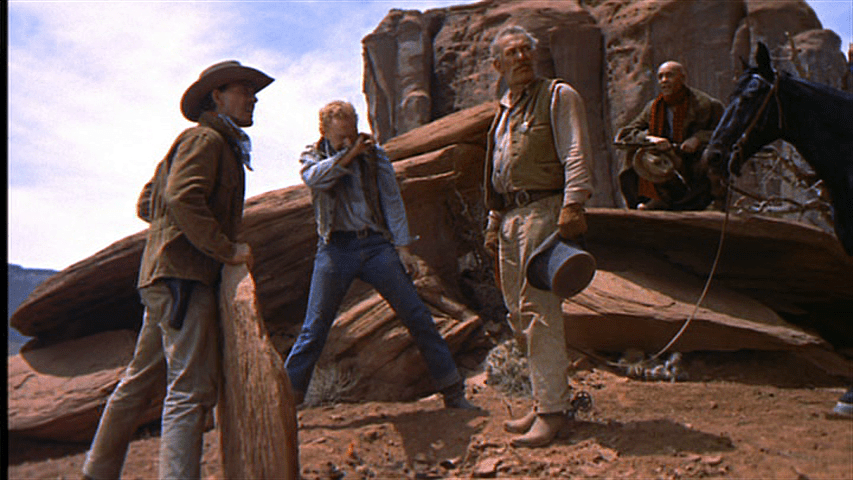

Ethan continues the search alone with Brad and Marty because, as Clayton acknowledges, “this is a job for a whole company of Rangers, or this is a job for one or two men.”

Three become two a few minutes of screentime later when Brad suicidally confronts the Comanches alone after Ethan finds and buries Lucy’s defiled body, which we hear but don’t see:

The final two searchers lose the trail soon after. “We’re beat and you know it,” Marty says. Ethan’s reply is my favorite line in this or any film (obsolete pejorative slang aside), because it’s basically the inverse of my philosophy of life: “Injun’ll chase a thing till he thinks he’s chased it enough, then he quits. Same way when he runs. Seems like he never learns there’s such a thing as a critter’ll just keep comin’ on.”

They briefly return home to the Jorgensens in a sequence that features framing which ought to look familiar by now:

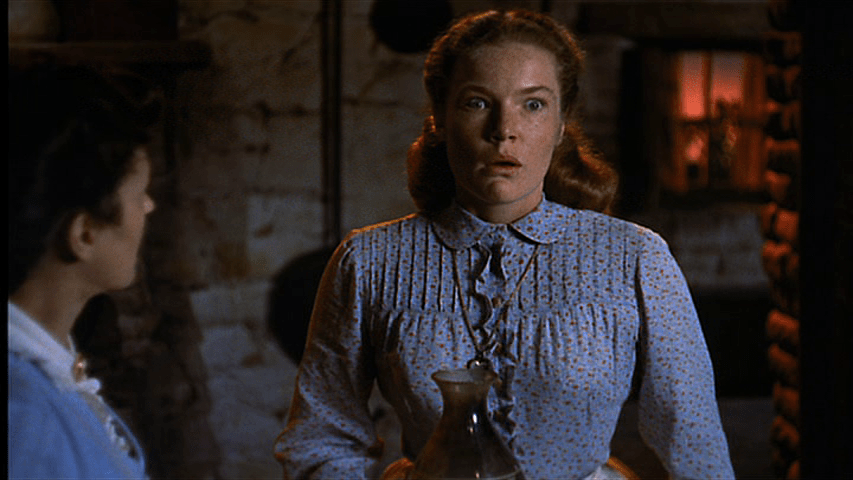

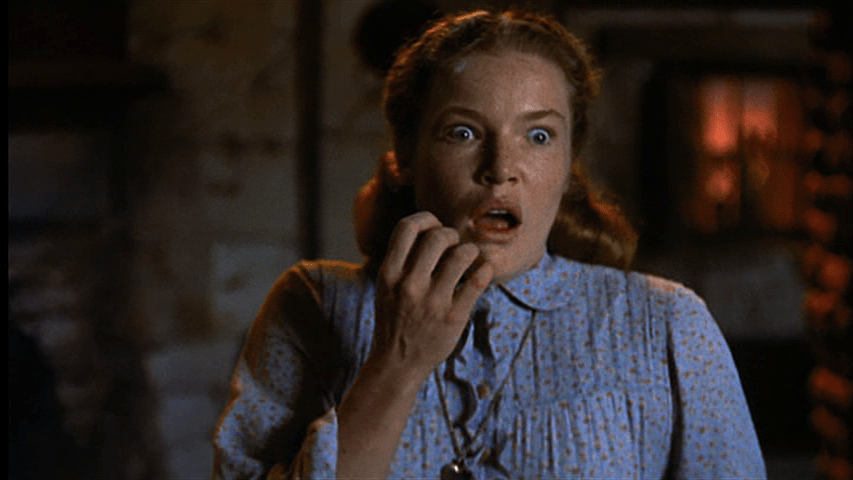

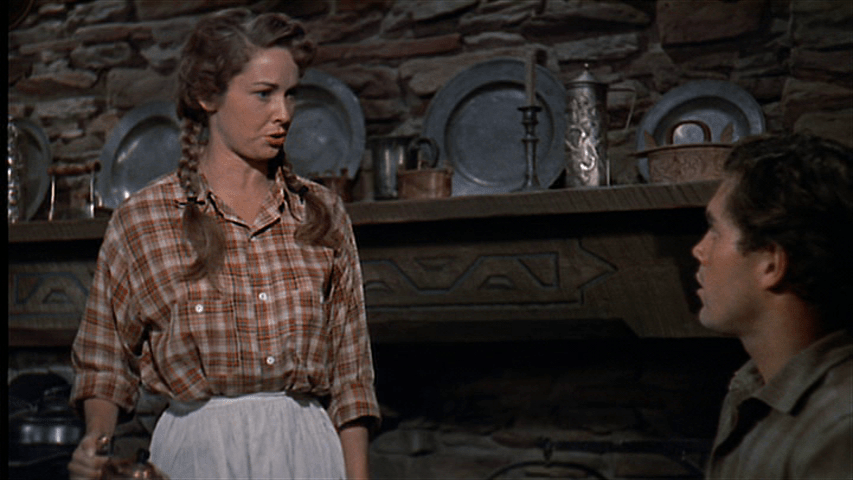

But are off again the next morning in pursuit of a lead that came to the Jorgensens in the form of a letter, much to the chagrin of daughter Laurie (Vera Miles), who reveals to Marty that “you and me have been goin’ steady since we was three years old.”

A big chunk of what happens next is shown in flashback as Laurie reads a letter that Marty writes to her, including his accidental (he thought he was trading for a blanket, not a bride) marriage to a woman named Wild Goose Flying in the Night Sky (Beulah Archuletta) that many people find distasteful in the way it’s played for comedy, but which M. Elise Marubbio defends as essential to understanding how “Ford’s direction throughout the film suggest an understanding of racism as a neurosis that permeates a community, including the viewer” in a chapter in the book Native Apparitions: Critical Perspectives on Hollywood’s Indians:

And an encounter with a cavalry troupe that has just massacred an entire Comanche village, including Marty’s wife, who ran off (possibly to look for Debbie) after she heard the two men talking about Scar.

Ethan and Marty finally catch up with him in New Mexico Territory, where the medal Ethan gave Debbie at the beginning of the film reappears during a conversation in which the chief reveals that two of his sons were killed by white settlers:

Debbie (now played by Natalie Wood) is there, too, and runs after Ethan and Marty when they leave to warn them they’re in danger:

When she tells them, “these are my people,” Ethan pulls his gun.

But Marty is having none of it:

They’re interrupted by a poison arrow which wounds Ethan in the shoulder and escape (without Debbie) to a nearby cave where they fend off another attack:

And where Ethan attempts to write a will that leaves all of his possessions to Marty on the grounds that he has “no blood kin,” to which Marty says, “I hope you die.”

Which finally brings us to the wedding in the screengrab at the beginning of this post, where Laurie, who McBride and Wilmington describe as “resplendent in the virginal white of her wedding dress,” harshly echoes the sentiments Marty almost just stabbed Ethan for when he tells her he has to leave one last time to retrieve Debbie, who they’ve just been notified is camped nearby with Scar and the rest of his band. “Fetch what home?” she cries. “The leavings of Comanche bucks sold time and again to the highest bidder with savage brats of her own? Do you know what Ethan will do if he has a chance? He’ll put a bullet in her brain. I tell you, Martha would want him to.”

This leads pretty directly to the film’s key moments. Marty daringly sneaks into the camp alone and convinces Debbie to leave with him, but has to kill Scar in self defense, raising the alarm.

The Rangers ride in after them, and Ethan claims Scar’s scalp, which judging from his face doesn’t bring the closure he expected:

Just then he spots Debbie:

Marty tries and fails to prevent him from riding after her:

And Ethan catches up with Debbie in front of another cave:

Robert Pippin writes in Hollywood Westerns and the American Myth that The Searchers revolves around the mystery of what happens next:

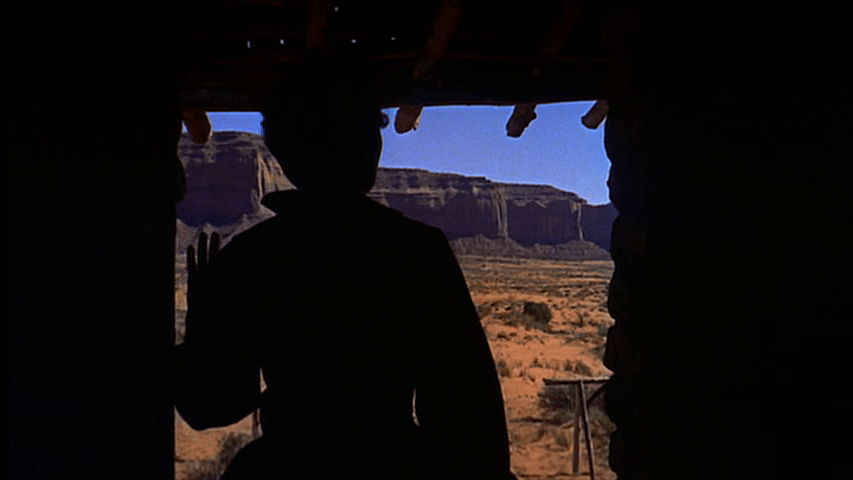

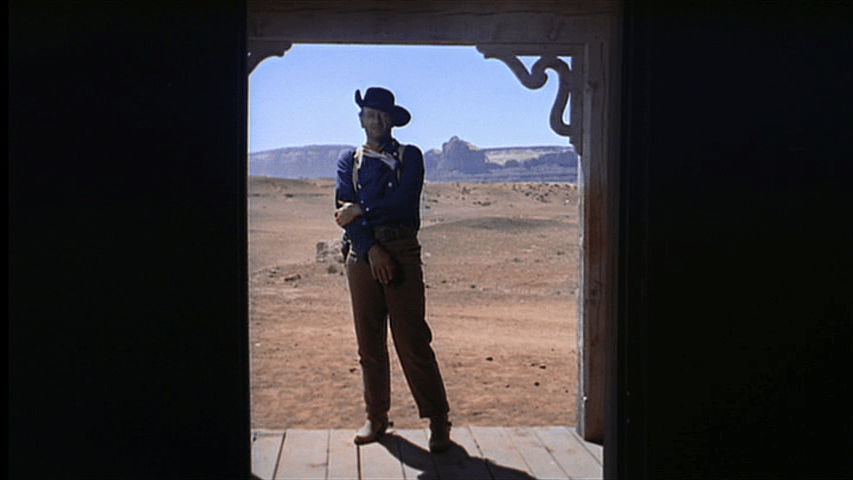

To Glenn Kenny it’s “an unabashed and matter of fact depiction of the mysterious workings of grace” which can’t be parsed in any rational way, while to Pippin “what we and [Ethan] discover is that he did not know his own mind, that he avowed principles that were partly confabulations and fantasy.” Whatever the case may be, and while I find Ethan every bit as compelling a character as I did in my youth when I first discovered this film, what I find myself pondering the most these days is what this scene and the final one that follows it say about America. After all, as Jeffrey Church points out in an article published in the journal Perspectives on Political Science, “the film is not called ‘The Searcher.'” Much ink has been spilled about the way Ethan stands alone in the final scene after Mr. and Mrs. Jorgensen (Olivia Carey) take Debbie inside, then Laurie and Marty push past him:

I think it’s absolutely essential to note that after John Wayne, the actor, clutches his arm in a moving homage to silent film star Harry Carey (father of the actor who plays Brad and husband to the actress who plays Mrs. Jorgensen), Ethan, the character he plays, chooses to turn and walk away:

Girgus reads Marty’s presence as “dramatically [subverting] Ethan’s wish to form a nation of one without any responsibility to anyone outside of himself” by turning their search for Debbie into a social experience that mirrors “the situation of America as a democracy of continued relevance to its own people and for the world during a period of increasing activism by minorities and people of color,” which seems just as true today as it did in 1956 when The Searchers was released or 1998 when Girgus’s book was published. But where he argues that Ethan “cannot (my italics) enter the interior spaces of the house” despite the fact that he “represents steadfast masculine strength, power, and aggression that constitute essentials for the survival of any society, including a democracy,” Pippin emphasizes the absence of a reconciliation scene with Ethan and suggests that he may instead be recusing himself from participating in the one taking place within because it is “while not a complete fantasy, much more fragile than those ‘inside’ are prepared to admit.”

My point with all this is that Ethan is, to borrow some phrases from the film, “a human man.” As are, of course, the Comanches he spends its runtime opposing. And the country built on their bones is indeed “a fine, good place to be.” But it can be even better. So let’s spare a thought for all of them as we gather around the communal punch bowl this Thanksgiving, because those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it.

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.