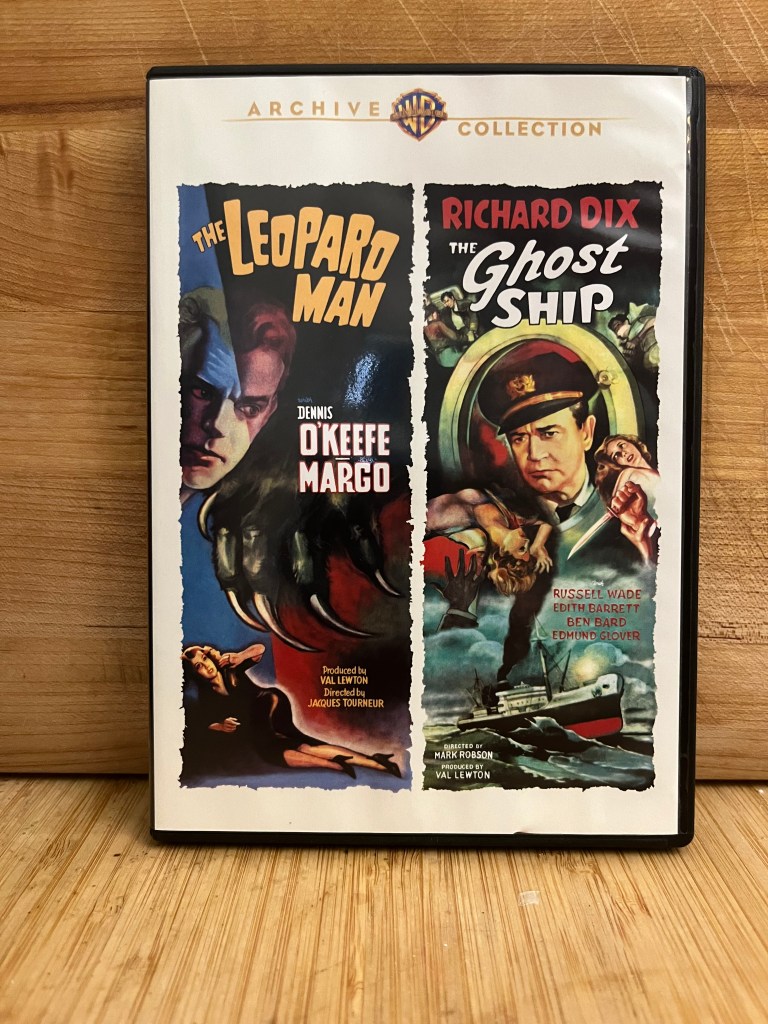

I had so much fun creating a double feature for last year’s October Drink & a Movie post that it was an easy decision to do it again. This time I’m celebrating the film I’ve long thought of as my favorite B movie, The Leopard Man, and the one which recently stole that crown, House of Usher. Here’s a picture of my Warner Archive Collection DVD copy of the former:

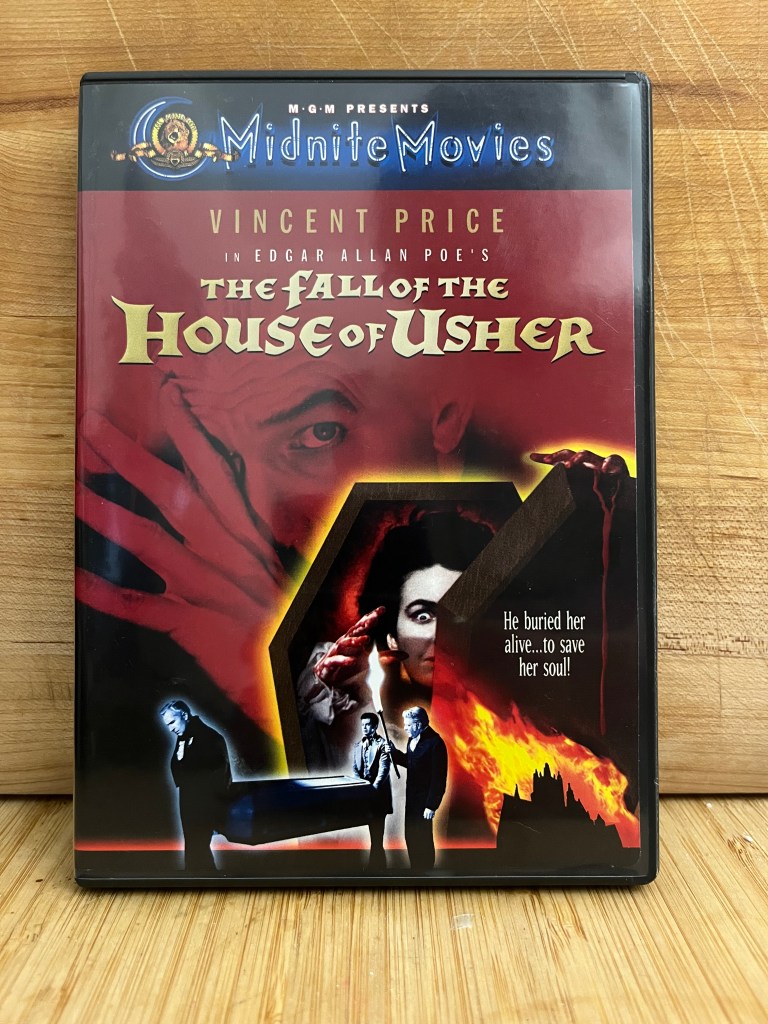

And here’s a picture of my MGM “Midnite Movies” DVD edition of the latter:

The Leopard Man is also currently streaming on Watch TCM until November 19 and is available for rental and purchase on a variety of platforms, while House of Usher can be rented and purchase on Apple TV+.

This month’s beverage pairing was admittedly inspired primarily by The Leopard Man‘s title, but although the Lion’s Tale would almost certainly be too spicy for the delicate palate of Vincent Price’s Roderick Usher (as Paul Clarke notes in The Cocktail Chronicles, where the recipe we use comes from, a little bit of St. Elizabeth Allspice Dram goes a long way), its bold pumpkin pie spice flavors make it a perfect match for the film he appears in and other scary season fare. Here’s how you make it:

2 ozs. Bourbon (Evan Williams Single Barrel)

1/2 oz. Lime juice

1/2 oz. Allspice liqueur (St. Elizabeth)

1 tsp. Simple syrup

1 dash Angostura bitters

Shake all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled cocktail glass.

Clarke garnishes this drink with a lime wheel, which is probably what I would do if I was making it during the summer, but in the fall we typically serve it unadorned as pictured above. In addition to its name, I was drawn to the Lion’s Tale right now because I’ve been itching to make a bourbon drink before my bottle of Evan Williams Single Barrel, far and away the best you can get at its price point, runs out. Without too many other ingredients to compete with, this is a great showcase for it. If you’re using a less full-bodied whiskey, consider employing a 2:1 simple syrup to counter the pungency of the lime juice and allspice liqueur.

Both films featured in this post are about contagion, but neither involves a literal disease. In the case of The Leopard Man, it’s bad luck which is passed from character to character. The film begins with P.R. man Jerry Manning (Dennis O’Keefe) introducing his star client Kiki Walker (Jean Brooks) to his latest idea for drumming up publicity, a tame leopard:

At first Kiki isn’t impressed:

But then Manning explains that he envisioned Kiki making a grand entrance with the cat during the act of a rival performer named Clo-Clo (Margo):

Kiki and the leopard do cut a striking figure together:

And initially the stunt achieves its desired affect of getting everyone’s attention; however, Clo-Clo takes exception to having the spotlight stolen from her, and deliberately frightens the leopard with her castanets in what interestingly appears to be a point-of-view shot from the perspective of the cat:

It recoils, then lunges away into the night, but not before scratching the hand of a waiter:

Later that evening everyone is looking for the escaped leopard. A boy shines a flashlight on Clo-Clo’s legs:

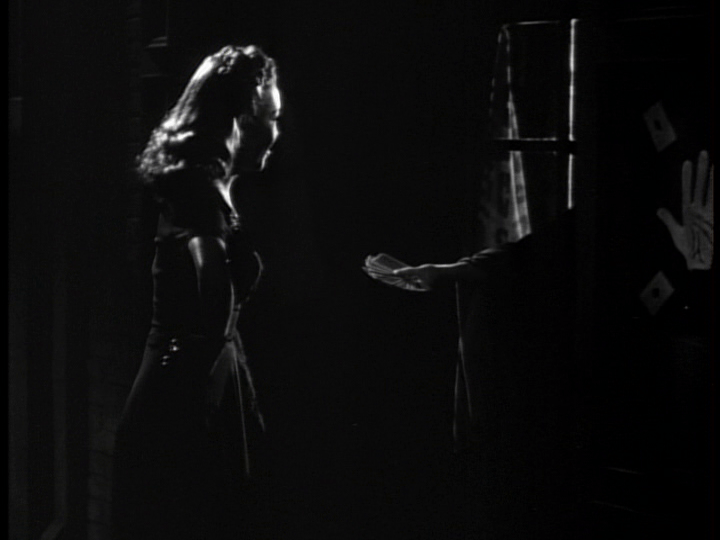

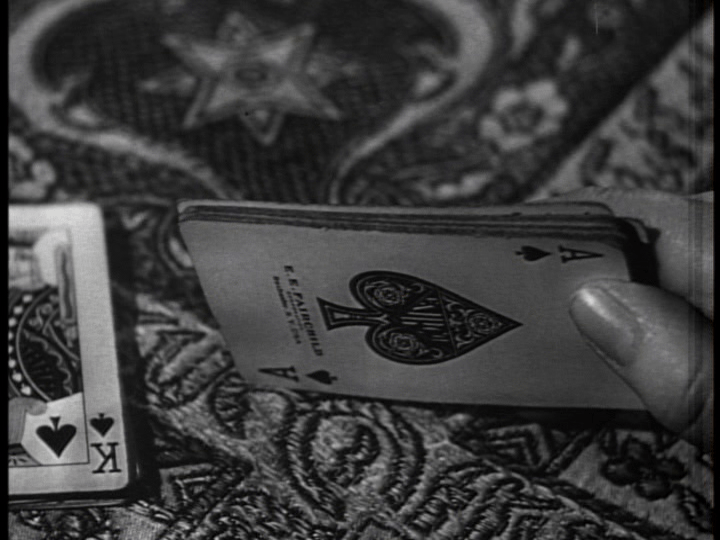

She stamps and the light goes out, but the camera stays with her as she walks through the streets. A fortune teller friend Maria (Isabel Jewell) calls out, “take a card, Clo-Clo, see what the night holds for you.”

Her face tells us everything we need to know about the significance of the ace of spades she draws:

But she quickly recovers and flicks it away, calling “faker!” back over her shoulder:

Clo-Clo greets people as she passes them and the camera stays with her until suddenly it doesn’t. “Hello, chiquita,” she says to a girl in a window, and with that the narrative torch has been passed:

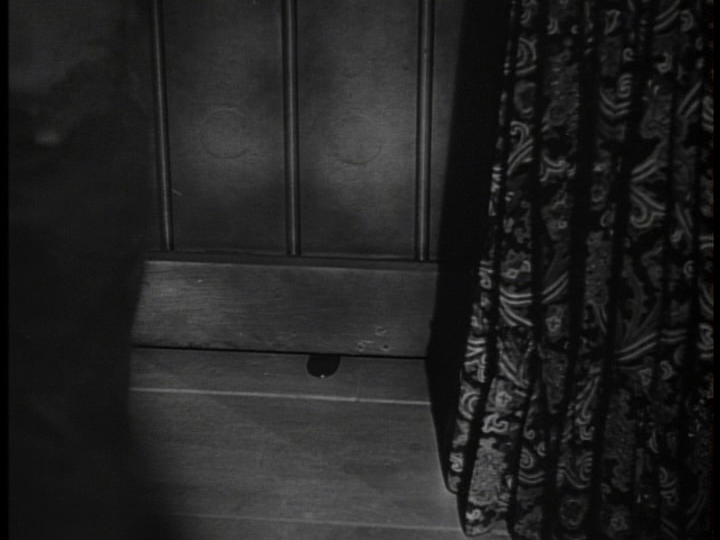

This is Teresa Delgado (Margaret Landry) and she is about to be sent on a nighttime errand to get cornmeal for the tortillas for her father’s dinner in a scene which lasts five full, harrowing minutes of screentime and ends with the unforgettable image of her blood seeping through the crack beneath her front door:

The film spends some time investing in exposition after Teresa’s funeral. A posse is formed to track down the animal that killed her. Maria reads Clo-Clo’s fortune again, but no matter how hard she tries to avoid it, the ace of spade keeps appearing. “What did they say before the bad card came up?” she asks. “You will meet a rich man and he will give you money,” Maria replies. Finally, Jerry introduces Kiki to a local museum curator named Galbraith (James Bell) who was on the posse with him. At dinner that night Galbraith gestures at a fountain with his pipe and says, “I’ve learned one thing about life. We’re a good deal like that ball dancing on the fountain. We know as little about the forces that move us and move the world around us as that empty ball does about the water that pushes it into the air, let’s it fall, and catches it again.”

The next scene picks Clo-Clo up again as she tries to sweet talk a flower seller into giving her a free rose. “My mistress, Señora Consuelo Contreras, does not have to beg for flowers. She won’t miss one,” says another customer (Fely Franquelli).

As was the case with Teresa Delgado, the camera stays with her, but this time only for awhile. Consuelo (Tula Parma), the girl she works for, actually turns out to be both our new subject and the next murder victim, and the moments just before her death feature another POV shot, we think showing a branch bending under the weight of the leopard that’s about to kill her:

Except that at the crime scene the next morning, Jerry offers a different theory: “it might not be a cat this time,” he suggests to a skeptical police chief (Ben Bard) and Galbraith.

The second half of the film chronicles his efforts to prove his hunch correct. Clo-Clo receives $100 from the wealthy benefactor Maria saw in her future, but the death card is still after her and the scene after it appears one final time is her last.

Everyone thinks she’s the leopard’s third victim except Jerry, who correctly interprets signs that Clo-Clo put lipstick on right before she was killed as evidence that her murderer was a man. When the skinned, week-old carcass of the cat is found shortly afterward in a canyon that Galbraith searched by himself earlier, he finally has a suspect. Kiki and Consuelo’s boyfriend Raoul (Richard Martin) help him successfully set a trap. Galbraith escapes, though, and flees into a procession that commemorates the slaughter of a peaceful village of Native Americans by Spanish conquistadores, which per J.P. Telotte links his crimes to that tragedy “to suggest a continuum of such inexplicable human horrors”:

Jerry and Raoul quickly apprehend him and extract an explanation of sorts as they drag him away: “I didn’t want to kill, but I had to.”

Speaking specifically about Consuelo he continues, “I looked down. In the darkness I saw her white face. The eyes full of fear. Fear! That was it. The little frail body, the soft skin. And then, she screamed.” Suddenly a shot rings out and Galbraith falls dead, shot by Raoul. As Telotte notes, this is a superficially classic resolution: “The publicity agent-detective has played his hunch and unraveled a murder mystery; the killer has confessed and is killed in retribution.” Except that this isn’t how the movie ends. The final images are instead of Jerry and Kiki walking away as Robles informs Raoul that he will have to stand trial for Galbraith’s death in the background:

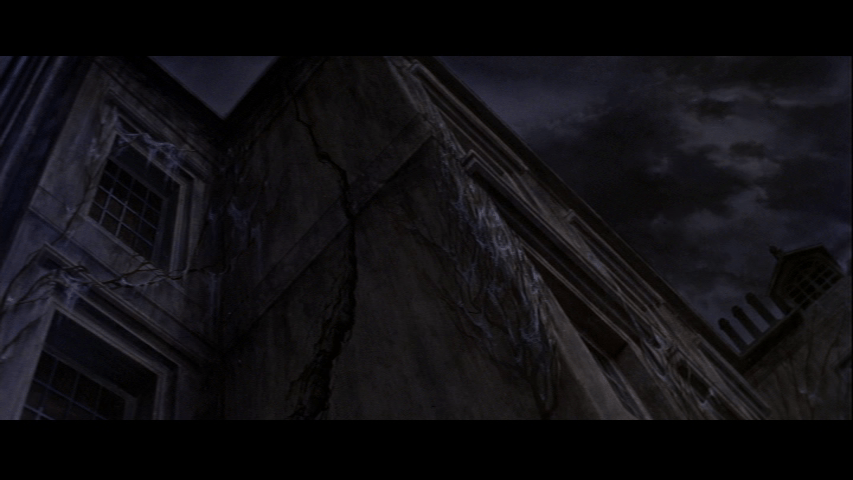

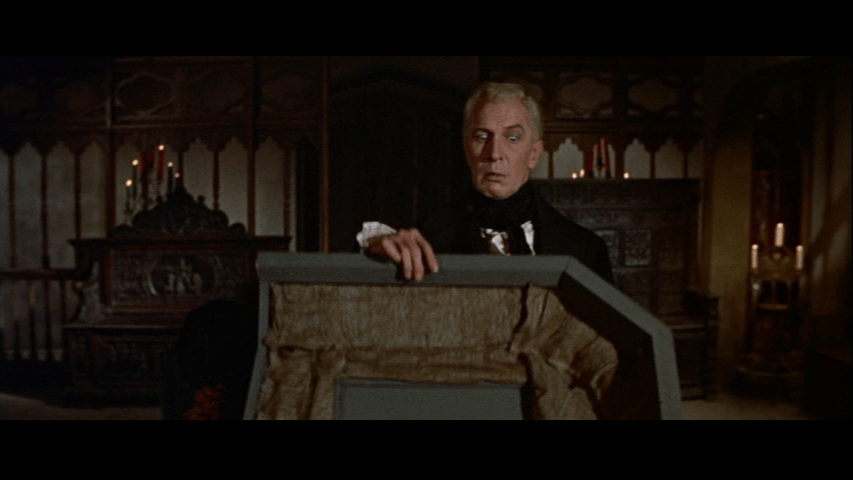

The parting reminder that Raoul must be punished because “he too bears that murderous potential, a dark and unpredictable possibility that society, for its own preservation, has to repress” leaves us “with a sense that there is no real ending yet in sight, certainly no true consolation here for the victims’ families, and no satisfying feeling that things have at least been ‘made right,’ just a disturbing residue from these terrible events.” Chris Fujiwara, writing in his monograph about director Jacques Tourneur, suggests that The Leopard Man‘s disturbing effect derives from the fact that the doom which circulates from character to character represents “a debt that no one owes and that is owed to no one but that nonetheless insists on being paid.” There is no such doubt about who must pay the bills in House of Usher, at least not in the mind of the last male heir of the titular family. He lives in a mansion which we encounter at the beginning of the film as Mark Damon’s Philip Winthrop rides up to it through a desolate landscape that director Roger Corman explains in his autobiography How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime he opportunistically shot following a forest fire:

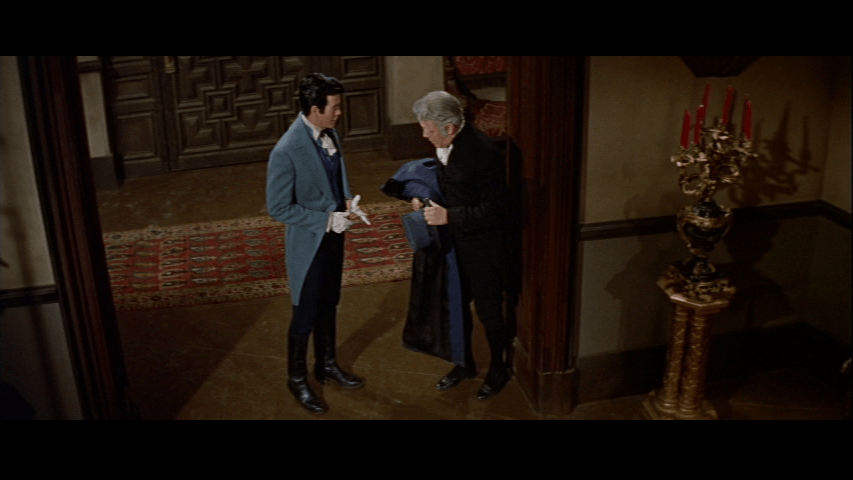

He is admitted inside by a servant named Bristol (Harry Ellerbe), who cryptically asks him to remove his boots in a high-angle shot which almost seems like it’s from the house’s perspective:

We learn why in the next scene. Roderick, who is none too pleased by Philip’s presence, is afflicted with hypersensitive hearing: “sounds of any exaggerated degree cut into my brain like knives,” he explains.

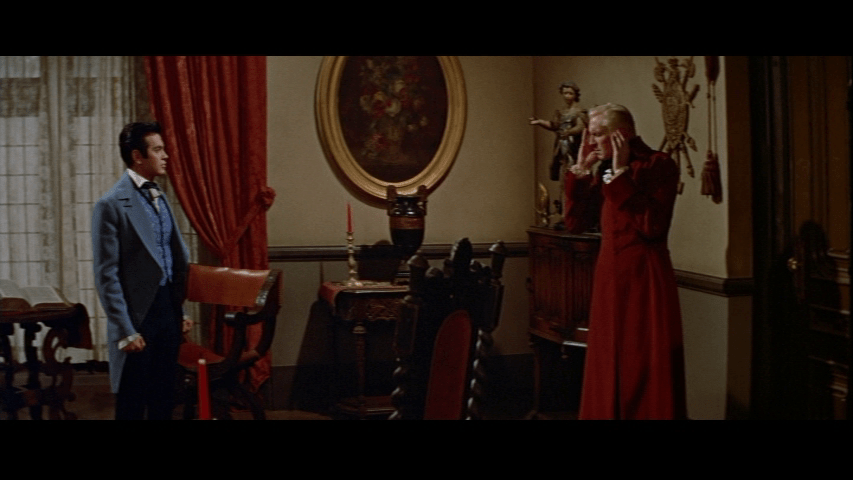

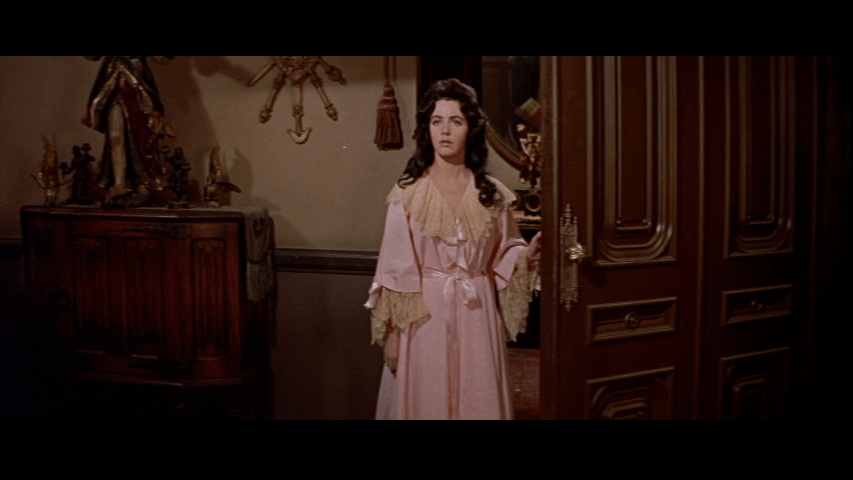

Roderick orders Philip to leave, but Philip informs him that he isn’t going anywhere without his fiancée Madeline (Myrna Fahey). She is supposedly bedridden, but appears in the room moments later:

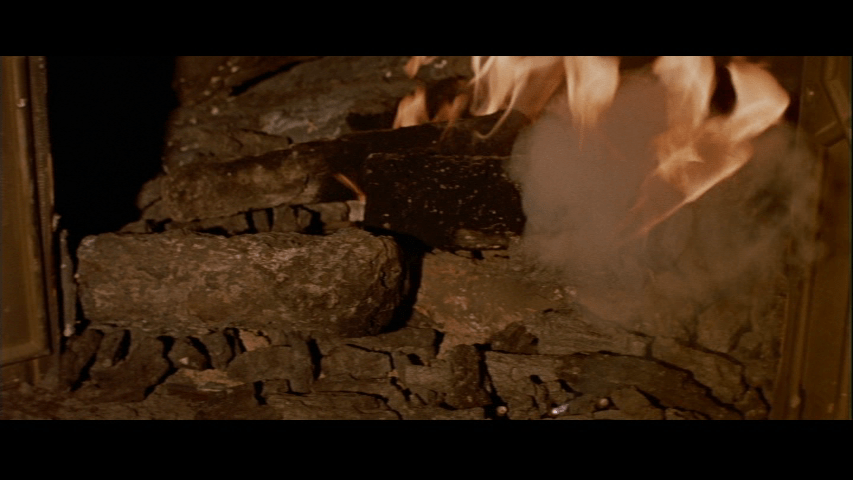

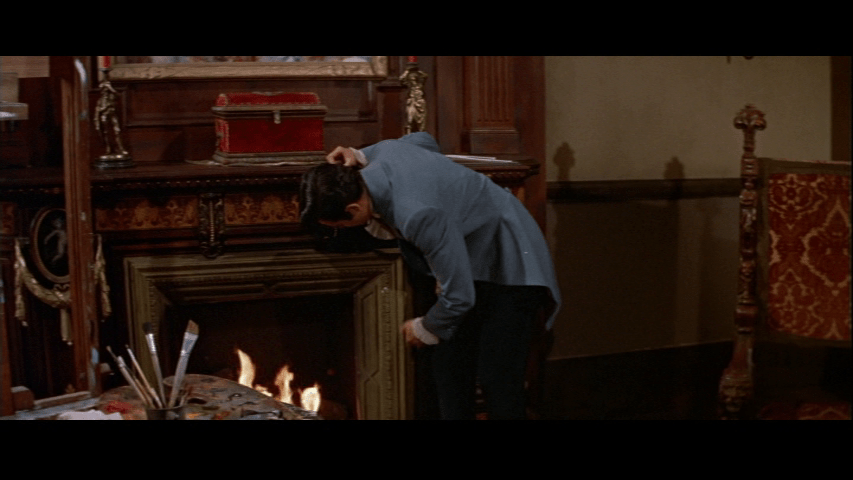

And that’s basically the film’s entire plot! Roderick reluctantly agrees to let Philip stay and leads Madeline back to bed. While they’re gone coals jump out of the fireplace and singe Philip’s pants:

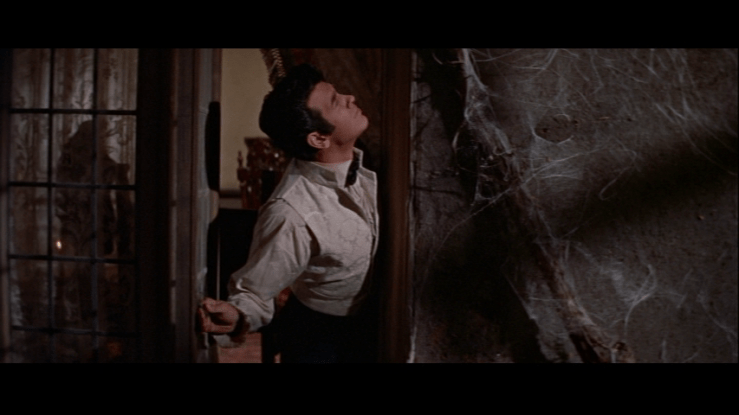

That evening the house trembles, and looking out the window Philip spies a crack running its entire length:

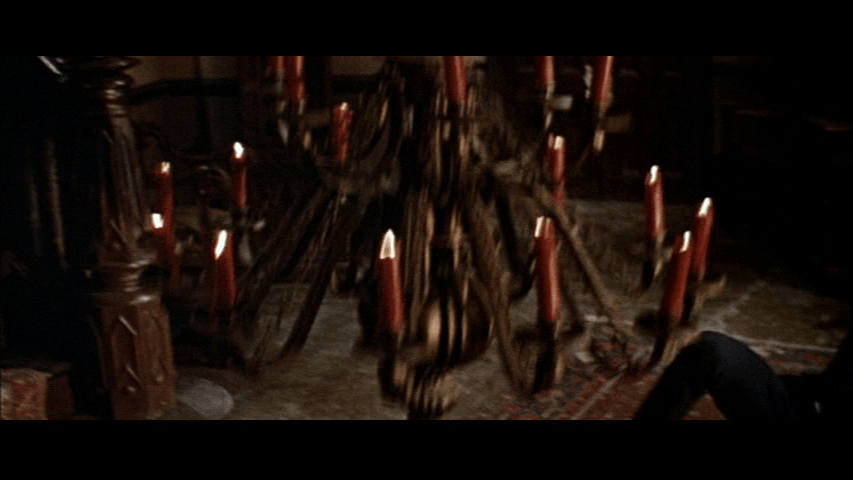

One his way down to dinner a few minutes later, a chandelier falls from the ceiling and misses him by mere inches:

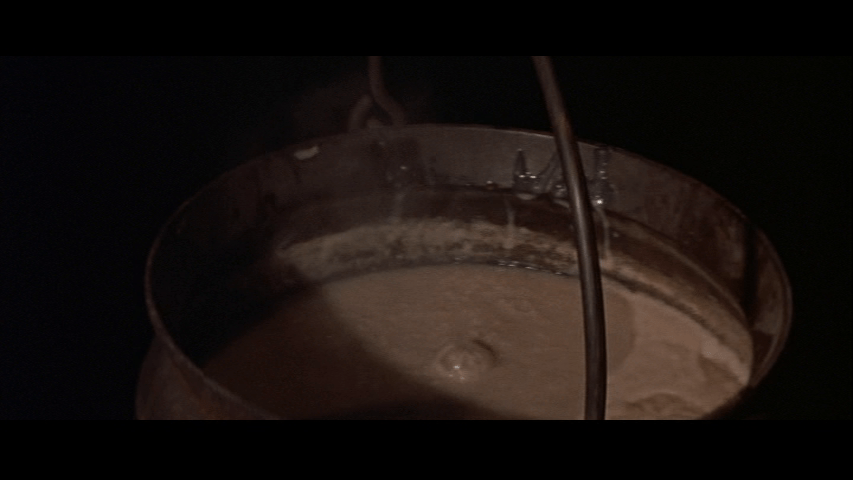

The next morning Philip visits the kitchen and says he wants to take Madeline’s breakfast to her. A cauldron of gruel, which per Bristol “is the most she’s ever eaten in the morning,” edges ever closer to Philip while they talk, but luckily Bristol notices before it burns him:

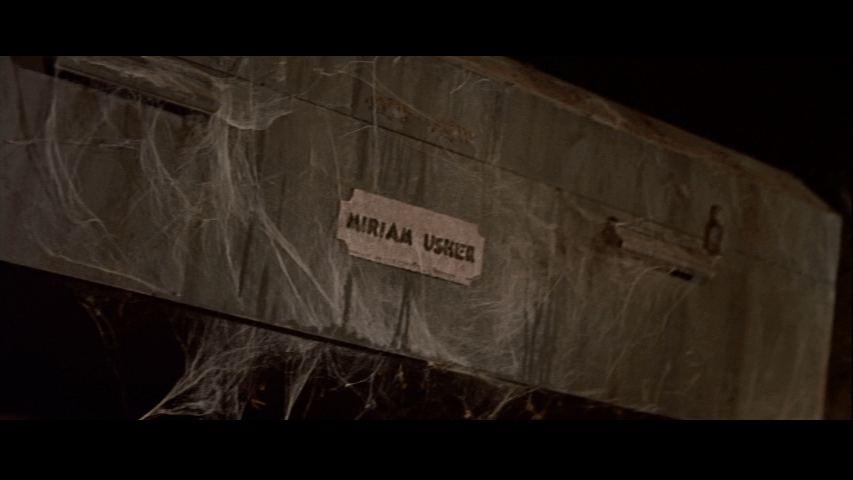

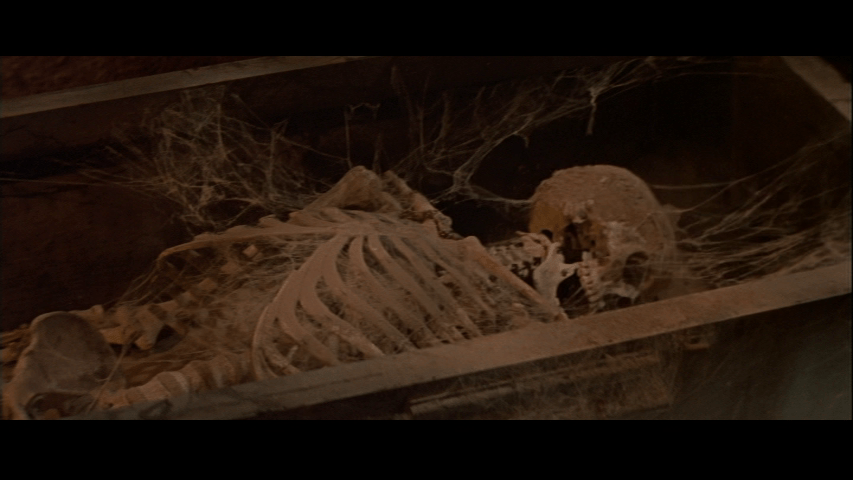

Up in Madeline’s room Philip tries to persuade her to leave with him. “Perhaps you’ll feel differently after you’ve seen,” she says, and takes him downstairs to the family crypt. She shows him the coffins of her great-grandparents, grandparents, parents . . . and an empty one labeled “Madeline Usher.”

Suddenly, as they talk a coffin tumbles down nearly on top of them:

“I think you still do not understand,” Roderick tells Philip in the aftermath of this incident, “and I think it’s time that you did.” They repair to the balcony, where Roderick explains that the land around the house once was fertile, which is depicted through an effectively haunting camera effect:

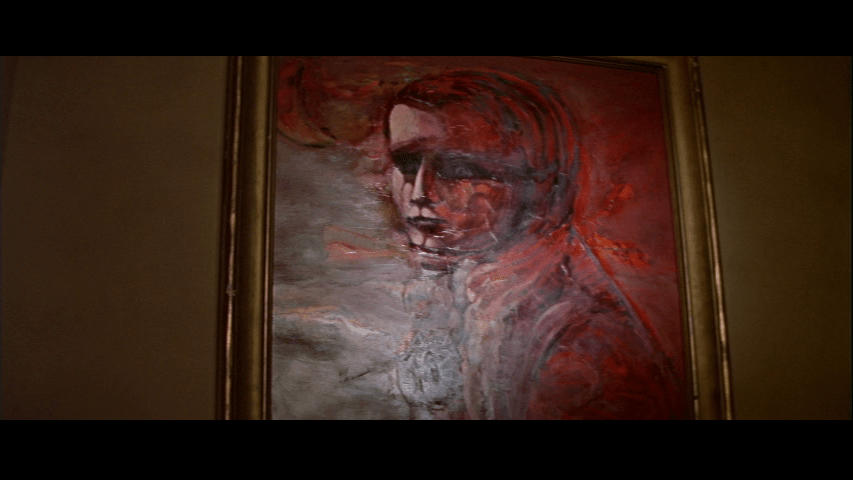

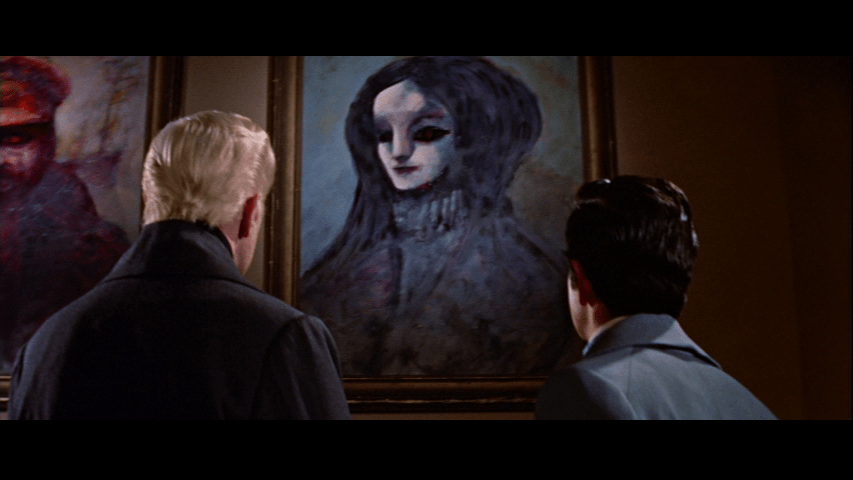

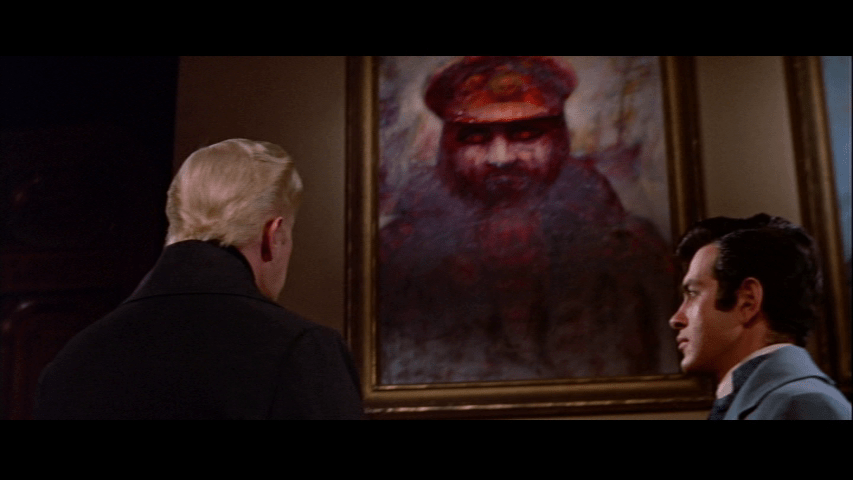

Then they go back inside for my favorite scene, a history of the Usher line accompanied by close-ups of each family member’s anachronistically modern portraits and a list of their crimes. Anthony Usher was a “thief, usurer, merchant of flesh” and Bernard Usher was a “swindler, forger, jewel thief, drug addict.”

Francis Usher was a “professional assassin,” while Vivian Usher was a “blackmailer, harlot, murderess. She died in a madhouse.” Finally, Captain David Usher is identified as a “smuggler, slave trader, mass murderer.”

At the conclusion of the tour, Roderick shares the thesis which governs his life:

This house is centuries old. It was brought here from England. And with it every evil rooted in its stones. Evil is not just a word. It is reality. Like any living thing it can be created and was created by these people. The history of the Ushers is a history of savage degradations. First in England, and then in New England. And always in this house. Always in this house. Born of evil which feels, it is no illusion. For hundreds of years, foul thoughts and foul deeds have been committed within its walls. The house itself is evil now.

In an interview with Lawrence French, Corman suggests that the fictional painters of these portraits (which in real life were created by artist Burt Schoenberg) “may have been picking up the distortion from the evil in the minds of the people he was painting.” This would be another example of transmissibility, but I like My Loving Wife’s explanation that they are a creation of the house better, especially since it reinforces the claim Corman makes in How I Made a Hundred Movies that in this film “the house is the monster.” Consider this exchange between Roderick and an incredulous Philip from the same scene:

RODERICK: Mr. Winthrop, do you think those coals jumping from the fire onto you were an accident? Do you think that chandelier falling was an accident? Do you think that falling casket was an accident?

PHILIP: Are you trying to tell me that the house made those things happen?

RODERICK: Yes.

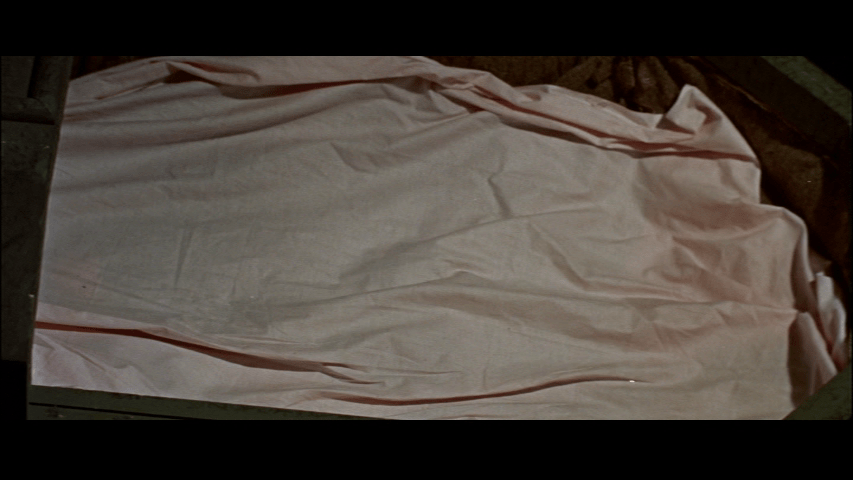

Philip is unconvinced, though, and shouts at Roderick, “I’ll tell you what’s evil in this house, sir: you!” He finally persuades Madeline to leave with him, but she dies before they can depart. Or so Philip thinks. We catch on before he does that all is not as it seems thanks to the twitch of a finger as she lies in her casket:

Philip doesn’t notice, but Roderick sure does, and he reacts exactly like you’d expect someone who just realized their beloved sister is actually alive to:

The next morning over coffee, Bristol accidentally lets it slip that Madeline was prone to catalepsies. Philip now suspects that they buried her alive, but when he breaks open her casket, it’s empty:

Things escalate quickly from here. Roderick won’t tell Philip where he has hidden Madeline’s body and Bristol doesn’t know. After a day of fruitless searching, Philip collapses into a tormented surrealist nightmare sequence featuring multiple generations of evil Ushers that ends with Madeline screaming:

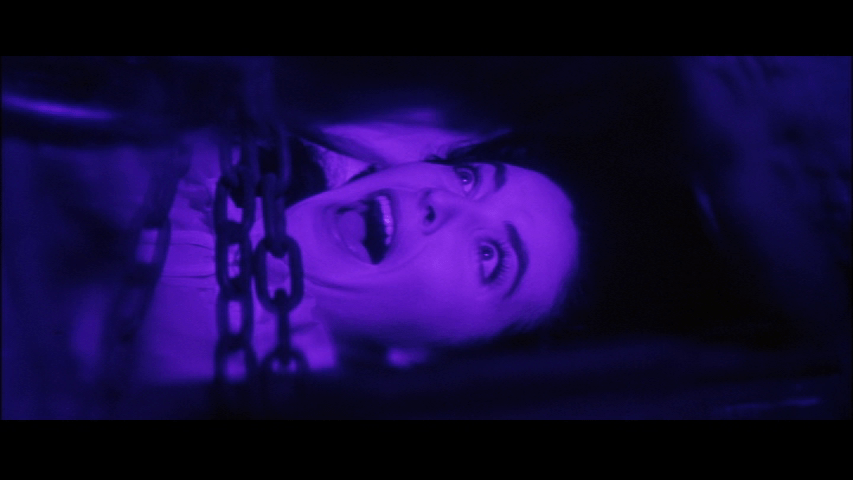

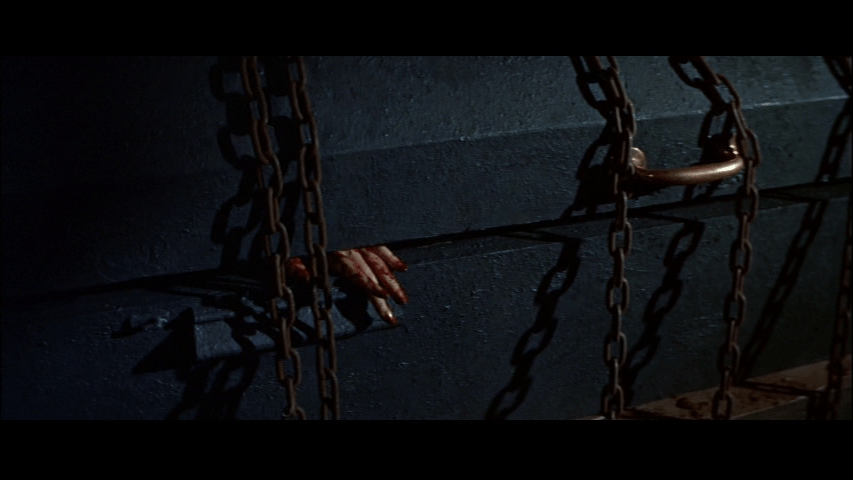

Upon awakening, he confronts Roderick again, who in the course of their conversation reveals that he is tortured by the sounds of Madeline moving even now. As he describes her “scratching at the lid with bloody fingernails, staring, screaming, wild with fury, the strength in her,” we cut to her bloody fingers emerging from beneath the lid of her coffin:

The climax includes a close-up of Madeline’s red eyes reminiscent of the murderous eyes of Sister Ruth which I talked about in my August Drink & a Movie post about Black Narcissus:

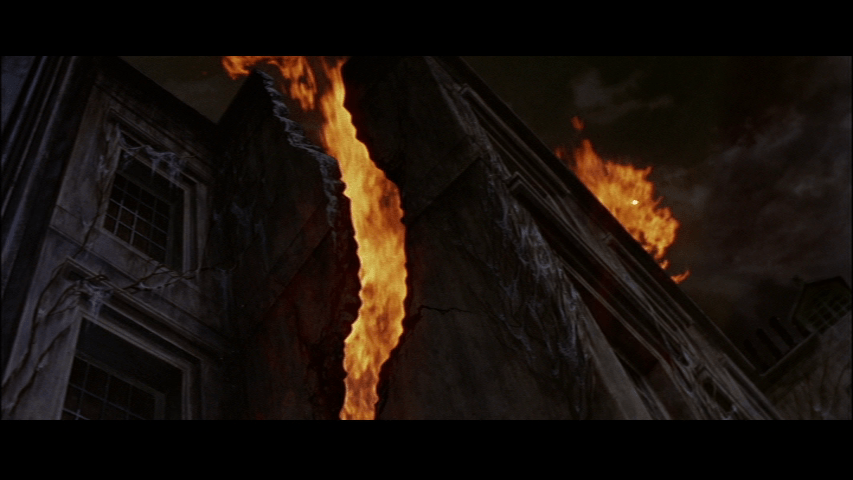

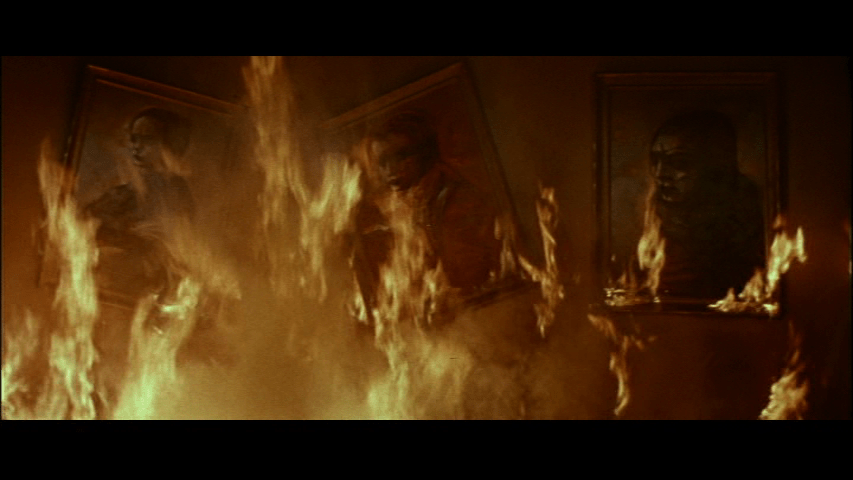

And lots and lots of fire:

With a presidential election looming, the political dimensions of these two films fairly leap off the screen, and viewed as a double feature, I think they do have a cogent message. It’s not enough to just remember our nation’s twin original sins of genocide and slavery like the participants in the ceremony which concludes The Leopard Man, but as demonstrated by House of Usher, guilt absolutely can be taken to nihilistic and pathological extremes. What unites them even more directly is their compactness: with runtimes of 66 and 79 minutes respectively, these are two of the most brilliantly concise films you’re ever going to see. Which, come to think of it, is another thing they have in common with a Lion’s Tale–after all, it’s basically just a whiskey sour with extra zip. So here’s to good ingredients and technique and letting them speak for themselves!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.