Although the majority of it technically falls within summer, it’s hardly any wonder that in the United States the month of September is more closely associated with fall when it marks the beginning of the school year, return of football, and appearance of pumpkin beer on grocery store endcaps. This makes the Autumn Winds created by St. Louis bartender Matt Seiter and collected in Gary Regan’s The Joy of Mixology a perfect cocktail to highlight right now because it uses sage, which I’ll always associate with Thanksgiving stuffing no matter how many times I combine it with ingredients like peaches and tomatoes, to whisper of the season to come while still offering up enough lemony brightness to make it a great porch sipper. Here’s how you make it:

2 ozs. Gin (Citadelle)

1/2 oz. Bénédictine

1/2 oz. Brown Butter Sage liqueur (recipe follows)

1 dash Angostura bitters

Make the Brown Butter Sage liqueur by browning 10 tablespoons of butter, stirring constantly, over medium heat. Remove from heat, add 3/4 oz. lemon juice and a chiffonade of 12-15 sage leaves, and rest for 10 minutes. Add 1 cup simple syrup and 12 ozs. vodka (Tito’s) and allow to stand at room temperature for 4-6 hours. Refrigerate overnight, skim solids from the top of the mixture, and strain into a bottle. Make the cocktail by shaking all ingredients with ice, straining into a chilled champagne coupe, and garnishing with a spanked fresh sage leaf.

If you’ve never spanked a sage leaf, it’s exactly what it sounds like, and you don’t want to skip this step as it releases odors that are essential to the way the drink works. Regan mentions that a small amount of butter solids will remain in the liqueur even after straining, which is true, and that it’s best to shake the bottle before mixing to make sure you get all of that flavor. Seiter calls for Ransom Old Tom, the first gin I ever fell in love with, in this Feast Magazine article, and I’m sure it works great, especially in late September when it actually starts to get cold! But I like Citadelle because it resonates not just with baking spices in the liqueur, but also the lemon, plus it’s an additional (along with the Bénédictine) French connection to this month’s movie. Speaking of which:

History Is Made at Night contains one of the most deliriously happy endings in cinema history, but even more than most movies made in the 1930s, its atmosphere is redolent with signs of World War II. Here’s a picture of my Criterion Collection DVD release:

It can also be streamed via The Criterion Channel with a subscription, and some people (including current Cornell University faculty, staff, and students) may have access to it through Kanopy via a license paid for by their local academic or public library as well.

Andrew Sarris famously argued in The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 that “History Is Made at Night is not only the most romantic title in the history of cinema but also a profound expression of [director Frank] Borzage’s commitment to love over probability.” The specific paramours in this case are Charles Boyer’s Paul Dumond and Jean Arthur’s Irene Vail, who as the film begins is attempting to leave her husband, Colin Clive’s sadistic and irrationally jealous shipping magnate Bruce Vail. Unwilling to accept the possibility that she hasn’t been cheating on him, but unable to prove that she has, he devises a scheme to “catch” her in his chauffeur Michael’s (Ivan Lebedeff) arms in order to prevent the divorce from becoming final (because she will no longer be “blameless” in the eyes of the law). Unfortunately for Vail, Paul just happens to be putting a drunken companion to bed (“you can’t drink all of the wine in Paris in one night–it’s practically impossible!”) next door from the apartment where the tawdry scene will play out and hears something:

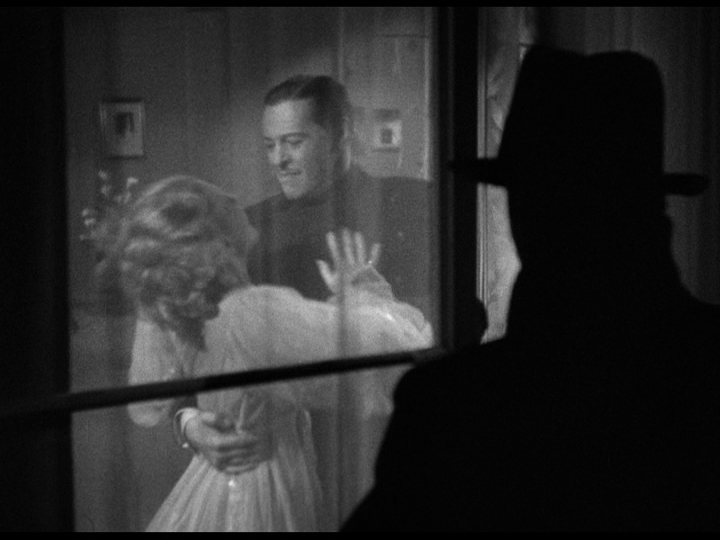

He creeps out onto the balcony and peers through the neighboring window:

When Michael begins to force himself on Irene, Paul makes a split-second decision to pose as a robber. He pulls his hat down over his eyes:

Climbs inside:

And lays Michael out with what Nick Pinkerton amusingly characterizes as “one of those right-on-the-chin one-punch knockout swings so prevalent in Golden Age Hollywood filmmaking”:

Just then Vail and his lawyer Norton (George Meeker) come rushing in. Paul holds them with a pretend gun (the old finger in the coat pocket trick):

“Steals” Irene’s pearl necklace and other jewelry as they look on and then orders her to get her coat:

Finally, Paul locks Vail and his lawyer in the closet and he and Irene make their escape:

Cue the film’s first of many major tonal shifts. As described by Hervé Dumont in his book Frank Borzage: The Life and Films of a Hollywood Romantic, “after this busy, Dashiell Hammett-like aperitif, regulated like a ballet and photographed in the style of film noir (Gregg Toland), we go into an English waltz.” Once they are alone together in a cab, Paul first offers a puzzled Irene a cigarette, then returns her necklace and jewels:

He explains that he is not, in fact, a thief and merely wanted to help her out of a sticky situation, to which she says, “all I can seem to say is ‘oh!'”

Paul proposes dinner and instructs the driver to head to an establishment called the Château Bleu when she accepts. Unfortunately, the neon sign out front goes out right as they arrive. This doesn’t deter Paul, who addresses the gentleman locking up (Leo Carrillo): “Cesare, you are not closing!” He replies, “no, we are not closing–we are closed!”

But Paul appears to know more about this man than just his name, and by playing to his vanity (“everyone here knows that you are the greatest chef in Paris, that is no news, but would you believe that you were that famous in America?”) convinces him to reopen the kitchen for a private engagement:

The musicians and their leader (George Davis) who preceded Cesare out the door are brought back even more easily by the mere mention of a champagne party:

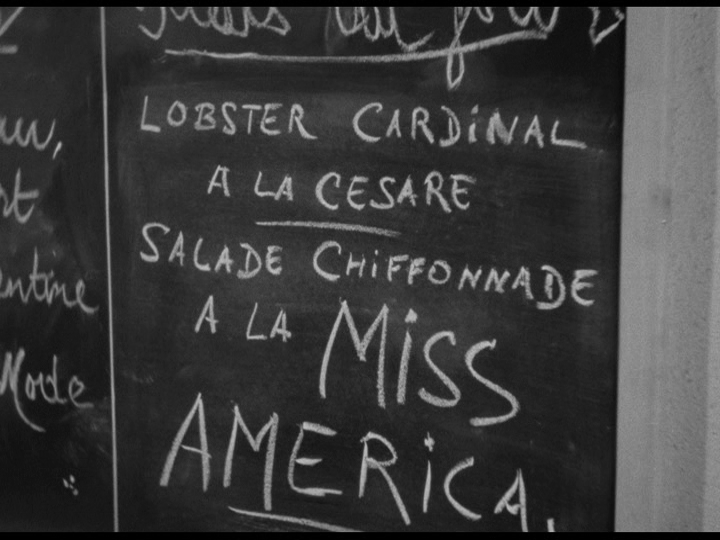

And with that what Dumont calls “the paradigm of sequence of seduction” is off and running. Paul orders lobster cardinale (which according to Saveur was invented in Baltimore, where I spent most of the 2010s, by the way) à la Cesare and salad chiffonnade. Then he draws a face on his hand, as one does, and introduces Irene to “the woman he lives with,” Coco:

I admit to feeling perplexed by this particular decision the first few times I watched History, but part of the shtick is that Coco doesn’t have a filter, which gives Paul a way to let Irene know that he is single and ask her what the hell precipitated the scene in her apartment earlier without technically violating societal norms. Dan Callahan further observes that when she reappears toward the end of the film, “Borzage uses this comic explosion to keep us off balance, unguarded, making us laugh so that when the lovers are reminded of their problems, we feel their pain much more deeply.”

Anyway, Paul and Irene tell Cesare to keep their food warm, much to his chagrin, and commence to dance until dawn, with Irene discarding clothing all the while. To again quote Dumont:

The camera frames Irene’s shoes, pans to her mink stole lying on the floor, and finally insistently follows the languorous steps of the dancers. The polysemy of images makes this erotic striptease–Irene is only wearing a long silk negligee–the outward expression of confidence and progressive abandonment (without saying a word, she says more to aul than she has ever said to her husband), but also one of detachment, of breaking off: jewels, shoes, and mink are signs of Bruce Vail’s property.

But although to them the night they have passed together qualifies as the year that Paul must wait as a gentleman before its in good taste for him to utter the one the “only thing important enough to say to [Irene] tonight,” they soon discover that they are not yet free to be together. Irene returns home, she thinks just to pack up her belongings, to find Vail waiting for her. He leads her and the police to believe that Paul’s blow killed Michael, when in reality he finished the poor guy off himself:

Then tells her that unless she joins him on a trans-Atlantic steamer that very afternoon, he’ll commit all of his resources to “finding the murderer.” Cut to Paul at the Château Bleu, where–surprise!–he is the head waiter. He recommends a French 75 to the man he put to bed the previous evening as a hangover cure, then writes the special du jour on a blackboard:

He’s expecting Irene to join him at five o’clock, and when his shift is over buys a newspaper to read while he waits. That’s when he sees this headline:

He resolves to follow Irene to New York, but locating her proves to be more challenging than he expected, because duh. Luckily Cesare decided to join him, and the two hatch a scheme to convince the owner of a restaurant called Victor’s to hire them to turn it into the hottest place in the city, which they do. Finally, one night Irene shows up in a dress that I’d *love* to see sparkle on a good nitrate print and claims the table he has ordered the staff to keep empty for her every night.

Sure, she’s with Vail, but yada yada yada the next thing you know she’s showing Paul how to make “eggs à la Kansas” the following morning:

And that, two-thirds of the way through History Is Made at Night, is when things *really* start to get interesting. Because, as noted by Brian Darr, screenwriters Gene Towne and Graham Baker appear to have intentionally capitalized on the 25th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic by ending the movie with a ship hitting an iceberg! There is, as yet, no hint of this in the breakfast scene depicted above, but on a postprandial stroll Irene lets it slip that the reason she and Vail were about to depart for Paris on the Hindenburg (seriously) was so that she could testify against the man arrested for the death of Michael. Paul barely hesitates: he and Irene will return to Paris on Vail’s boat the Princess Irene because he cannot allow an innocent man to go to the guillotine for a crime he believes he committed. And suddenly the stakes Borzage are gambling become clear. He is famous for placing obstacles between his romantic leads, but this one is a doozy even by his standards: the barrier is their own human decency. The film’s climax reenacts their star-crossed love affair, but on a bigger canvas to emphasize the universality of their plight. When Vail orders the captain of the Princess Irene to speed forward despite the hazardous conditions his vessel is sailing through, ostensibly to set a record but really to destroy Paul and Irene, he is no longer imperiling just their lives, but thousands of others.

Their union was already on death row, but once the ship starts sinking and its lifeboats fill up, the sentence is extended to hundreds of other couples.

The fundamental injustice of the two soulmates being separated from one another has been compounded, their sacrifice takes on even more heroic dimensions, and the only suitable reward is a miracle: although he and Irene don’t know it yet, Paul has already been acquitted, and a pardon comes through for their fellow passengers at the eleventh hour as well: “attention everyone, attention. The forward bulkheads are holding and the ship is in no danger of sinking,” comes the unexpected announcement. “Help is on the way. The lifeboats are standing by and you will soon be with your families.” Their reactions represent the full range of emotions that Paul and Irene, who for now still think they’ve only been granted a stay of execution, will presumably soon feel:

The final image of a kiss promises that our heroes truly will live happily ever after:

…at least until the Germans march into Paris about three years later. Of course, we could take things one step further and read the suicide of Bruce Vail as anticipating the end of that conflict. This, ultimately, is what connects this month’s movie and drink in my mind: the thing to remember about autumn is that it’s followed by winter, spring, and summer, just as war follows peace follows war. So be merry, pour yourself another glass of champagne, and have another helping of lobster cardinale:

Because the worst of times must by definition eventually get better, and nothing gold can stay.

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.

Outstanding! This is your best essay thus far..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Scott! Glad you liked it!

LikeLike