July is always the month of Bastille Day and the Tour de France and this year it also ushers in the Paris Summer Olympics, so I knew I was going to choose a French film to write about, but which one? I’ve long been meaning to highlight the Employees Only Martinez from Jason Kosmas and Dushan Zaric’s Speakeasy book, which has a dominant absinthe flavor that makes me think of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and the Moulin Rouge, so that seemed like a good starting point. From there it was a short hop, high kick, and cartwheel to my final destination, since with all due respect to John Huston, Baz Luhrmann, and the other filmmakers who have made it their subject, one film set in that famous establishment towers above the rest: French Cancan. But first, the drink! Here’s how you make it:

2 1/2 ozs. Gin (Drumshanbo Gunpowder Irish)

1/2 oz. Luxardo Maraschino

3/4 ozs. Dolin Blanc vermouth

1/4 oz. Absinthe bitters

Make the absinthe bitters by combining 3/4 cup absinthe (Kosmas and Zaric call for Pernod 68, but I used St. George Absinthe Verte because that’s what we currently have in our bar), 1/8 cup Green Chartreuse, 1 1/2 teaspoons Fee Brothers mint bitters, 1/4 teaspoon Peychaud’s bitters, and 1/4 teaspoon Angostura bitters in a small jar. Stir the amount of bitters that the recipe calls for and all of the rest of the ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled glass. Garnish with a lemon twist.

Speakeasy calls for Beefeater 24 gin, but I wasn’t able to find it in Ithaca so I went with Drumshanbo (which I had not previously tried) because the website The Gin is In described it as having a similar flavor profile, including the green tea notes which Kosmas and Dushan Zaric made a point of listing as a key aspect of their cocktail’s finish. We agree with them that the “super velvetiness” of Dolin Blanc is essential to creating a texture that makes the Employees Only Martinez a pleasure to sip. It also contributes floral and vanilla notes that play well with the anise and matcha that come from the other ingredients. This is a bigger drink at four ounces and a potent one, so handle with care, but it was the perfect accompaniment to the Greek salad with feta-brined grilled chicken that we had for dinner the other night, and I look forward to trying it with briny oysters sometime soon per Speakeasy‘s recommendation that it goes great with “raw bar of any kind.”

On to the movie! Here’s a picture of my Criterion Collection DVD release:

It can also be streamed via The Criterion Channel with a subscription, and some people (including current Cornell University faculty, staff, and students) may have access to it through Kanopy via a license paid for by their local academic or public library as well.

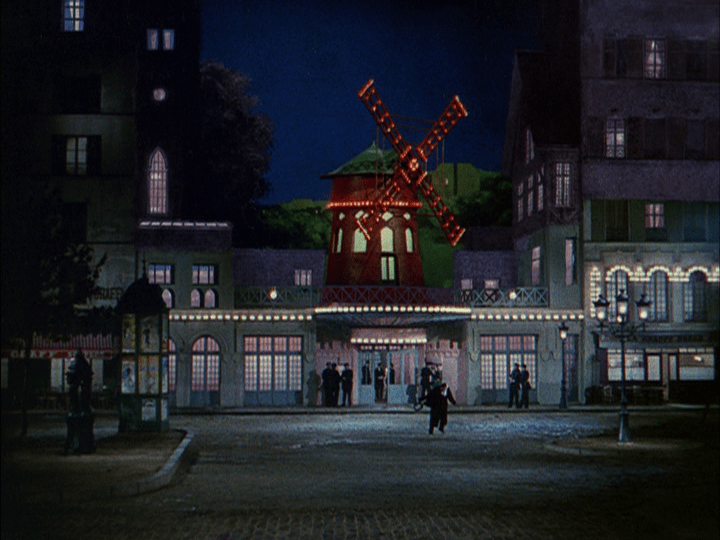

Although French Cancan begins with a notice that “this story and its characters are imaginary” and should therefore “not be seen to represent real people or events,” it’s transparently a fictionalized account of the Moulin Rouge’s founding. One night while slumming in Montmarte with rich patrons of his night club The Chinese Screen and his mistress/biggest star Lola de Castro de la Fuente de Extremadura aka “La Belle Abbesse” (María Félix), Jean Gabin’s Henri Danglard is struck by inspiration. As he explains later to his M.C. Casimir “le Serpentin” (Philippe Clay), “do you know what I’ll give them? A taste of the low life for millionaires. Adventure in comfort. Garden tables, the best champagne, great numbers by the finest artistes. The bourgeois will be thrilled to mix with our girls without fear of disease or getting knifed.”

He buys a dance hall called The White Queen with “drafts, promises, a lot of hot air,” and with the help of an investor named Baron Walter (Jean-Roger Caussimon) who knowingly shares Lola with him (“the precarious modern world judges by appearance only–respect them, and I’ll remain your supporter,” he tells Danglard) sets about transforming it. First, though, he returns to Montmarte, orders an absinthe, and waits for a young lady named Nini (Françoise Arnoul) who caught his eye on that fateful night out to wander by.

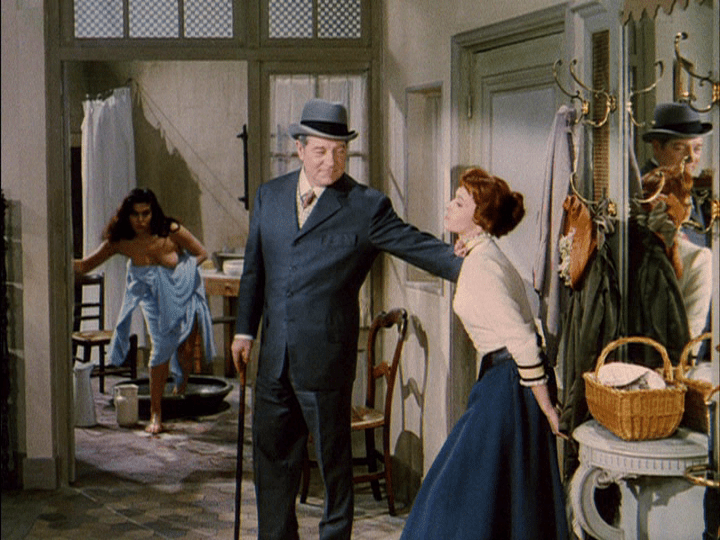

When she finally appears he follows her home and negotiates with her mother to secure her services in a scene which Janet Bergstrom has described as her “virtually sell[ing]” her daughter to Danglard:

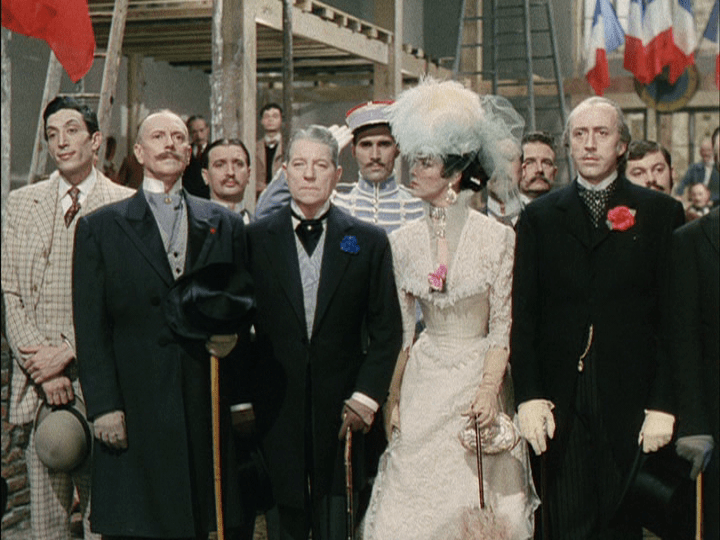

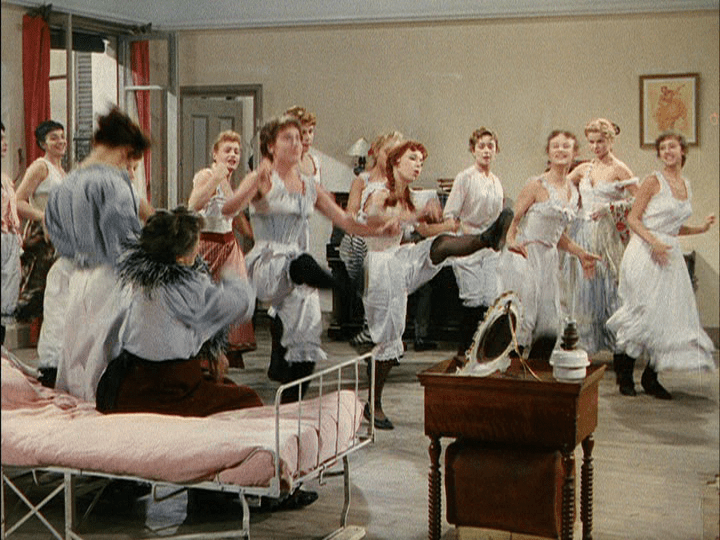

He then recruits an old friend named Madame Guibole (Lydia Johnson) to teach Nini and a number of other girls a now-passé dance that she was famous for back in the day called the cancan, which he has the bright idea to revive as the “French Cancan” to tap into a fad for English names. The plan is almost torpedoed when a Russian prince (Giani Esposito) infatuated with Nini draws Lola’s attention to her presence at a government official’s visit to the Moulin Rouge construction site by conspicuously kissing her hand as the “Marseillaise” plays, making Lola jealous because she immediately realizes that Danglard has brought her there:

Lola kicks Nini in the shin, causing a brawl to break out. As Danglard attends to her, a troublemaker eggs Nini’s lover Paulo (Franco Pastorino) on by observing that “the boss is lifting your girl’s skirts,” which ultimately results in him pushing Danglard into a pit:

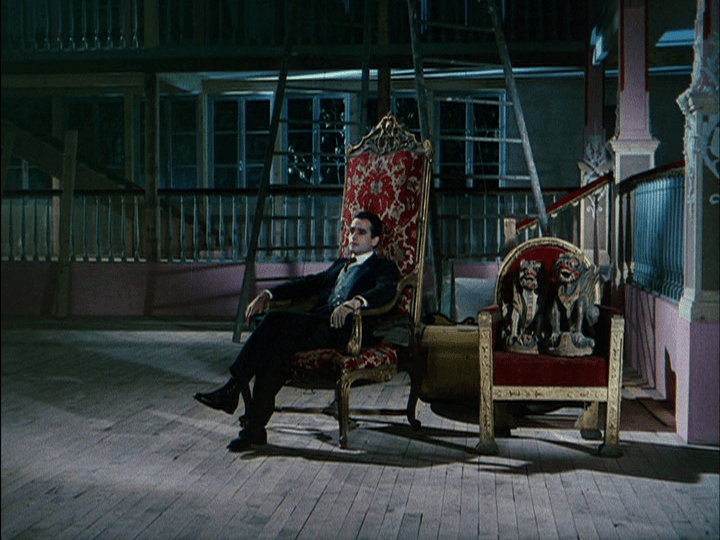

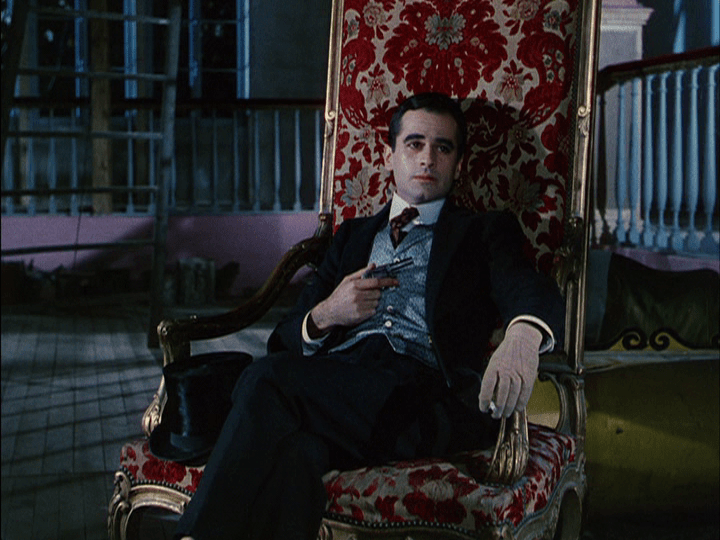

Baron Walter, enraged at the breach of Danglard’s verbal contract with him, withdraws his backing, but the prince steps in. Alas, he promptly tries to commit suicide when Lola makes him aware of the fact that Nini is love with Danglard following a remarkable scene in which he appears to sit motionless in a chair for many hours to confirm that they are indeed an item:

Luckily he bungles the attempt. He asks Nini for a “make-believe memory” that he can dazzle the younger generations with upon his return to Russia and they spend the evening touring all the Parisian hot spots in a sequence that features contemporary actors playing the biggest stars of the Belle Epoque, including Édith Piaf as Eugénie Buffet:

Afterward he presents Nini with the deeds to the Moulin Rouge in Danglard’s name (“it’s simplest”), but there’s one more rapids to navigate before the show can go on: Nini spies Danglard kissing his newest discovery Esther Georges (Anna Amendola) backstage on opening night and refuses to dance unless she can have him all to herself. A fiery speech by Danglard takes care of that, though:

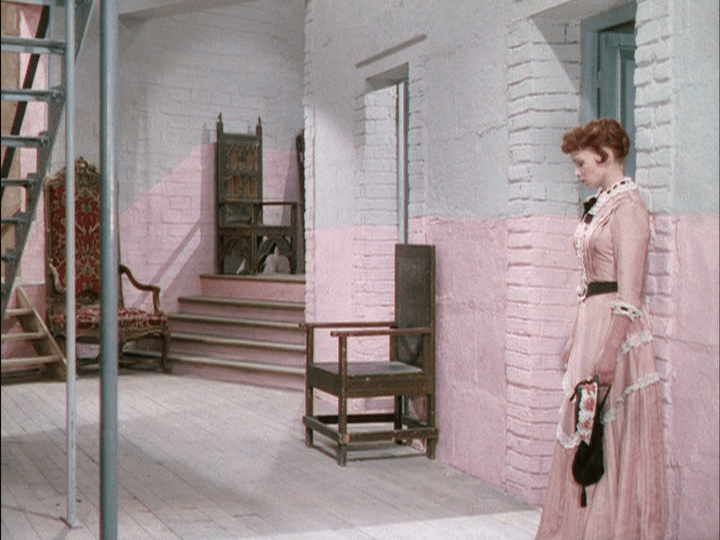

And per David Cairns a contrite Nini wearing a “camouflaged dress” is finally “absorbed into the theatre”:

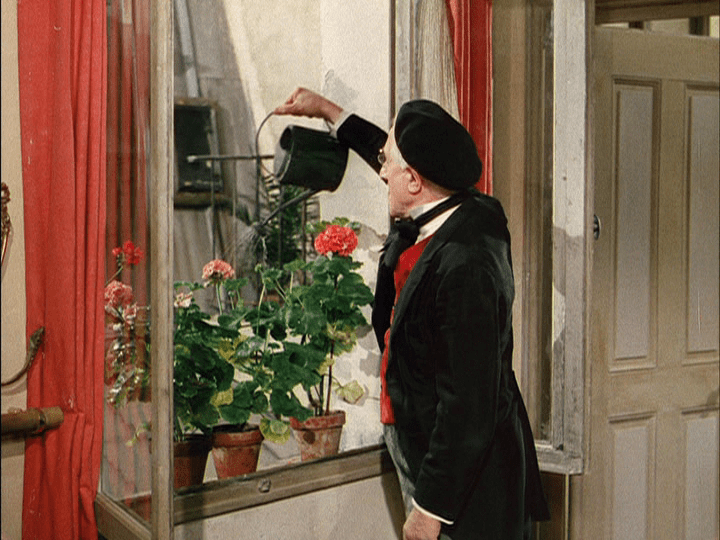

Bergstrom can’t forgive Renoir for what she calls French Cancan‘s “retrograde representation of male-female relationships,” a criticism which admittedly rings true when he and editor Borys Lewis place shots of Guibole leading Nini and her fellow dancers through a rehearsal next to one of pianist Oscar (Gaston Gabaroche) watering flowers:

But the film also contains multiple floods of women, which feels very much like an explicit acknowledgement that this is just a conceit–after all, dams break and, in the immortal words of Poison, “every rose has its thorns.” Here’s the first:

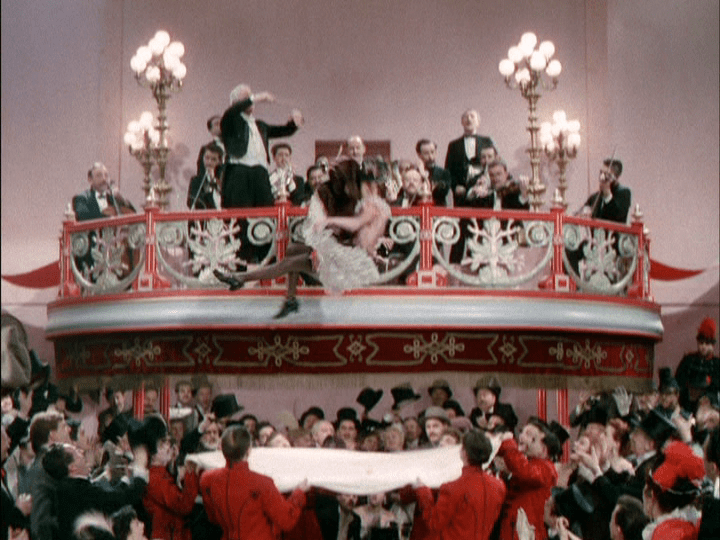

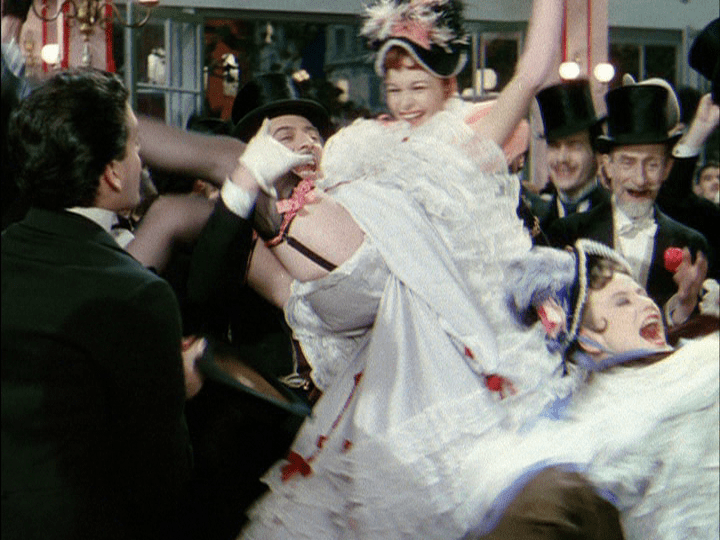

With the second being the nine-minute-long cancan that concludes the film which begins with dancers dropping from the ceiling, bursting through a poster on the wall, and leaping off a balcony:

And then explodes into a celebration of color and motion which is not merely the best thing about this film, but one of the most joyously spectacular sequences in all of cinema:

André Bazin writes beautifully about two other moments in his monograph on the director, which he offers in support of the statement that “Renoir’s is the only film I have ever seen which is as successful as the painting which inspired it in evoking the internal density of the visual universe and the necessity of appearances that are the foundation of any pictorial masterpiece.” First is the moment Danglard spots Esther from across an alleyway. “The decor, the colors, the subject, the actress, everything suggests a rather free evocation of Auguste Renoir, or perhaps even more of Degas. The woman bustles about in the half shadow of the room, then turning about, leans out the window to shake out her dustcloth. The cloth is bright yellow. It flutters an instant and disappears. Clearly this shot, which is essentially pictorial, was conceived and composed around the brief appearance of this splash of yellow.”

Next is this description of the young woman bathing in the background of the scene when Danglard takes Nini to Guibole’s for the first time. “She appears in the background through a half-open door, which she finally closes with a rather nonchalant modesty. This could well have been a subject dear to Auguste Renoir or to Degas. But the real affinity with the painters does not lie in this specific reference. It is a much more startling phenomenon: the fact that for the first time in the cinema the nude is not erotic but aesthetic.”

For Bazin moments like these combine to create the impression of “a painting which exists in time and has an interior development,” a sentiment echoed by his contemporary Pierre Leprohon, who says in his book Jean Renoir: An Investigation into His Films and Philosophy that “Renoir was not composing color canvases on the screen; he never forgot the essence of cinema, which is motion” and adds, “that is why French Cancan can be considered a major step in color films. It develops painting further without imitating it.”

Dave Kehr observes in his book When Movies Mattered: Reviews from a Transformative Decade that while Renoir frequently took actors as his subject, this is the first and only time he decided to make a film about a director, and that he shared more in common with his protagonist than just their common profession:

There is, obviously, a lot of Renoir in Danglard–Danglard’s work in creating his show exactly parallels Renoir’s work in creating his film, and Danglard’s revisionist cancan finds its aesthetic equivalent in the artificial Paris Renoir has fashioned to contain it. And we can assume that there is a lot of Danglard in Renoir, particularly his fashion of handling his performers, accepting their eccentricities along with their talents, and trying to bring out their most profoundly individual abilities. But direction is the most mysterious of creative processes, and Renoir knows to respect the mystery. What does Danglard do, exactly? Not much that we can really see. For the most part, he is simply there, observing intently and saying nothing. And yet the vision that emerges is Danglard’s vision, developed through an almost imperceptible series of choices and in flections. It is Danglard’s sublime passivity that makes French Cancan Renoir’s most direct and penetrating statement of the art of the movies. The director is the medium between the world and the image: he takes from people the reality that belongs to them and then sells it back in heightened form.

Cairns sees another statement about cinema in the parade of shots of people watching the climactic cancan which is positioned near the end of it.

“These are curtain calls for all the bit-players and leads in the film,” he argues, “and also a kind of farewell to an era, and also something else — a celebration of the audience’s role in the entertainment, and therefore a warm tip of the hat to us, watching on a TV or computer sixty years after Renoir made the film, a hundred and twenty seven years after the events depicted in the film failed to happen in as elegant and colourful a manner in reality.” This would, of course, make the stumbling drunk’s bow in French Cancan‘s final image ours:

Which as the author of a series called “Drink & a Movie” I very much appreciate. So here’s to you and here’s to me!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.