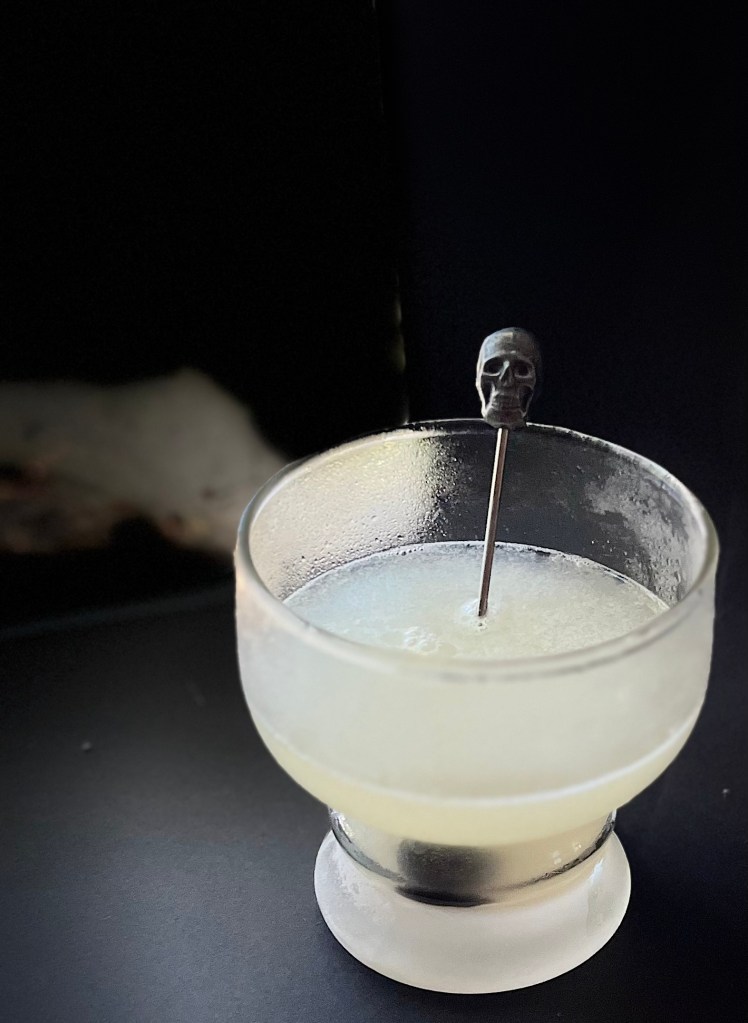

This month’s Drink & a Movie post is dedicated to Ithaca, New York legend Park Doing, who has one of the greatest Halloween rituals I’ve ever encountered. Each year he watches Harry Smith’s twelfth (I mention this because it’s sometimes referred to as No. 12) film Heaven and Earth Magic with whatever friends and neighbors find themselves at his house. It’s a non-intuitive, but inspired choice, which makes it absolutely perfect for this series. What I thought I’d do here is combine Park’s tradition with one my family borrowed from chef Grant Achatz a few years ago and a couple of new ones. Let us begin with a beverage. In Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails, Ted Haigh observes that the Corpse Reviver originated at the turn of the twentieth century as “more a class of drink than a single recipe” which was sometimes referred to simply as a “reviver” or an “eye opener.” In other words, it was originally meant to be imbibed in the morning! Albeit cautiously: as Harry Craddock notes in The Savoy Cocktail Book, “four of these taken in quick succession will unrevive the corpse again.” My recommendation is therefore to consume just one to give you fortitude at the beginning of the evening. Here’s how we make it:

3/4 oz. Dry gin (Broker’s)

3/4 oz. Lillet Blanc

3/4 oz. Cointreau

3/4 oz. Lemon juice

1 tsp. Absinthe (St. George Absinthe Verte)

Shake all ingredients with ice and strain into chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with a cherry impaled on a skull pick.

I shamelessly pilfered the skull and cherry presentation from local establishment Nowhere Special Libations Parlor, which uses it to striking effect. We prefer Craddock’s proportions for this drink, which if we follow David Wondrich’s lead once again like we did in August should lead us to use only 1/4 teaspoon of absinthe. Ted Haigh similarly calls for just 1-3 drops and Jim Meehan goes with a rinse in the PDT Cocktail Book, but we think a full teaspoon works wonders here. Broker’s has been our house London Dry gin for awhile, and we’re not the only ones–I’ve had at least three conversations recently about how it’s one of the best spirits values around right now!

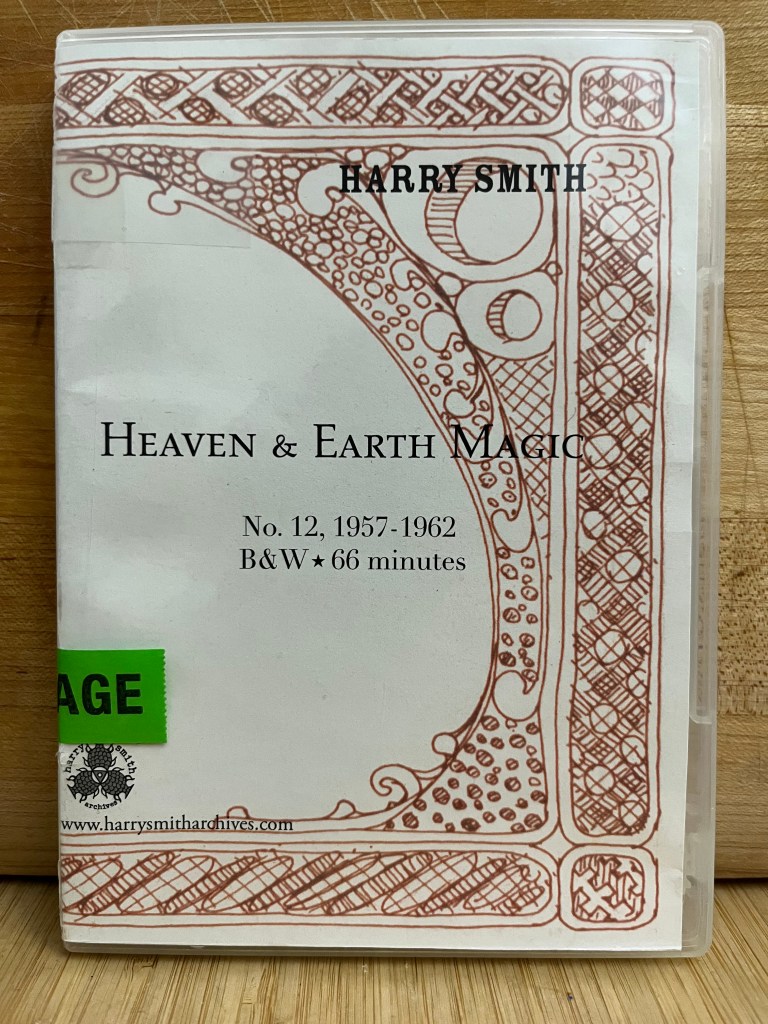

Next, of course, we have a movie. Here’s a picture of the Harry Smith Archives DVD release of the Heaven and Earth Magic that I borrowed via interlibrary loan:

I actually do own a DVD-R copy of the film that I bought off eBay awhile back, but I didn’t want to use images from it because its provenance is uncertain. I’d love to add a Harry Smith Archives edition to my personal collection, but unfortunately it has been out of print for ages.

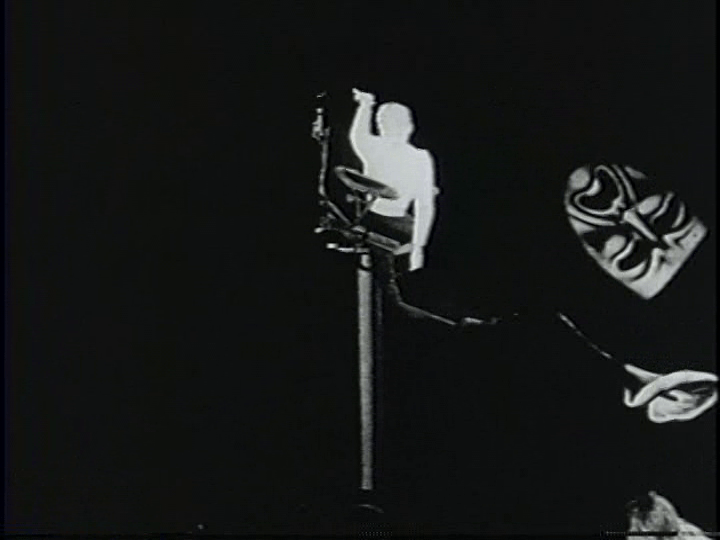

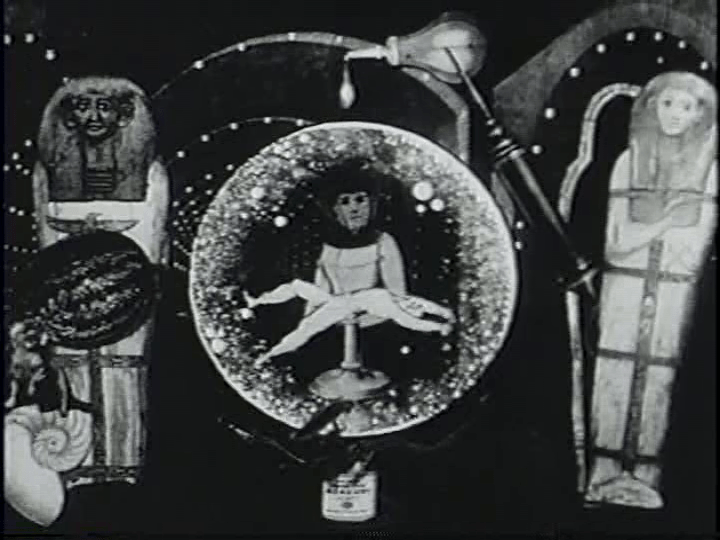

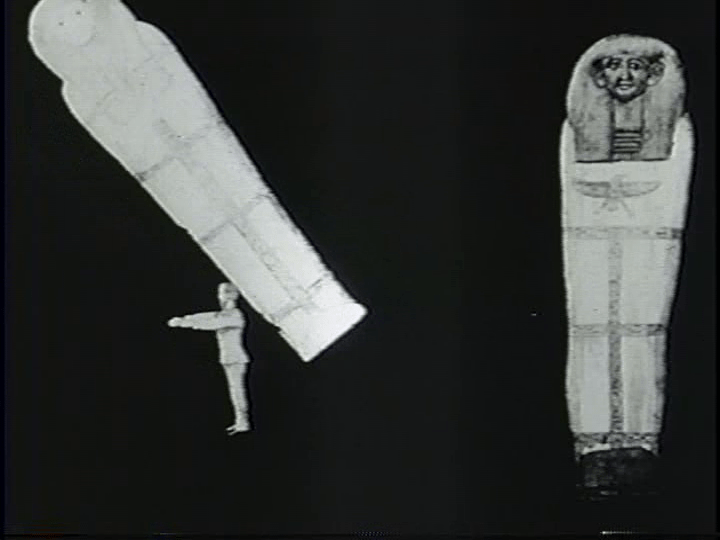

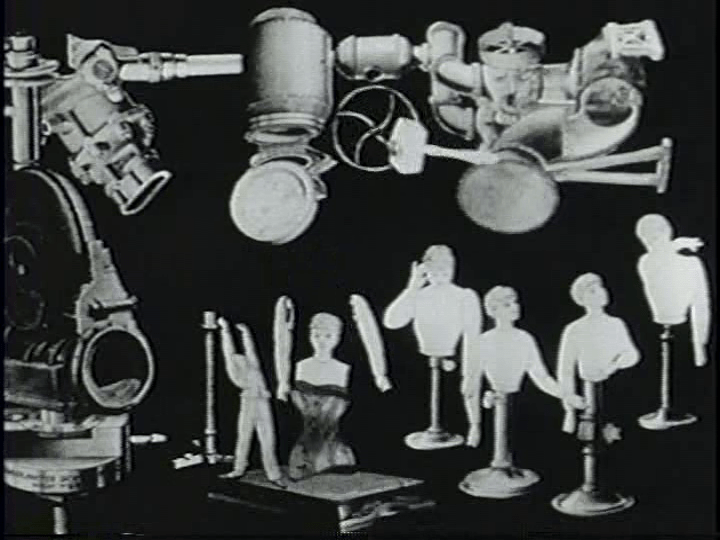

Most people’s primary source of information about Heaven and Earth Magic seems to be P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde, 1943-2000 which includes notes that Harry Smith composed for the catalog of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative which describe his “semi-realistic animated collages” as being part of his “alchemical labors of 1957 to 1962” and indicate that the film was made under the influence of “almost anything, but mainly deprivation.” They also summarize the movie’s plot:

The first part depicts the heroine’s toothache consequent to the loss of a very valuable watermelon, her dentistry and transportation to heaven. Next follows an elaborate exposition of the heavenly land in terms of Israel, Montreal and the second part depicts the return to earth from being eaten by Max Muller on the day Edward the Seventh dedicated the Great Sewer of London.

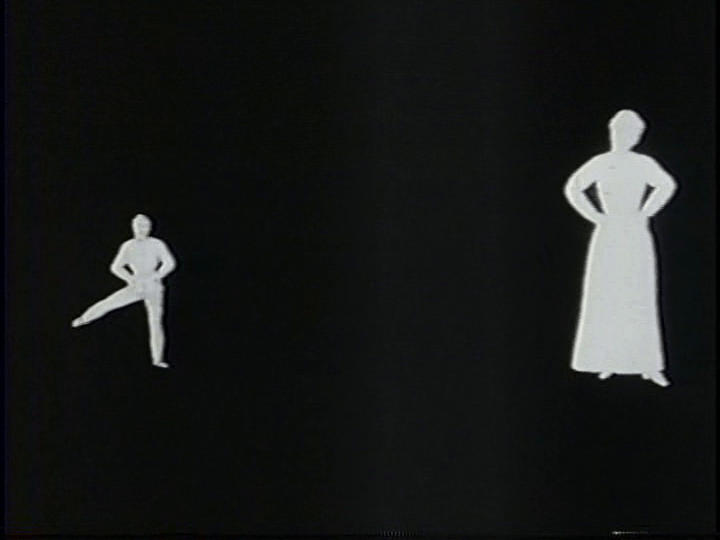

Sitney characterizes this synopsis as “ironic,” but notes that it is accurate in broad terms; he also provides his own interpretation. The main characters are a man and a woman:

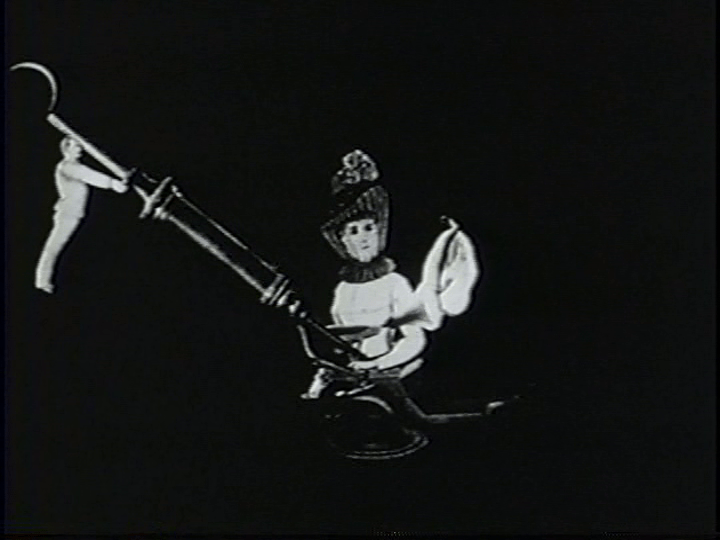

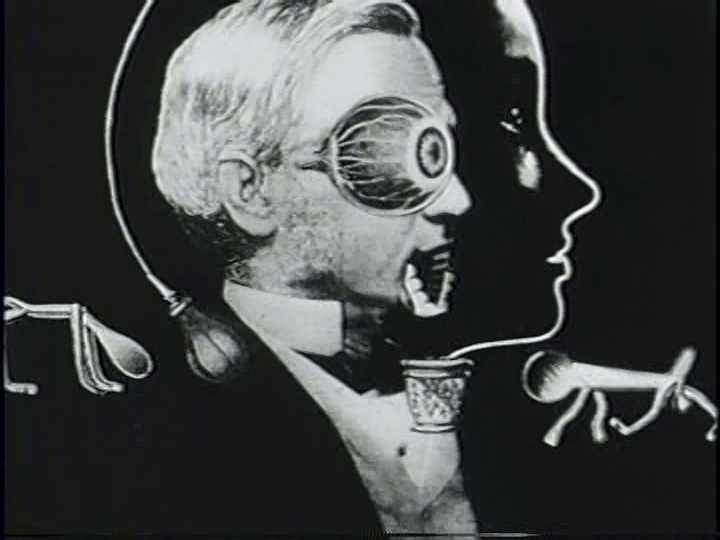

Like many of the film’s elements, both started life as engravings from a late-nineteenth-century illustrated magazine. Per Sitney, the man is identifiable as a magus by “his continual manipulations in the alchemical context of No. 12, coupled with his almost absolute resistance to change when everything else, including the heroine, is under constant metamorphosis.” As she sits in a “diabolical” dentist’s chair, the magus injects her with a magical potion:

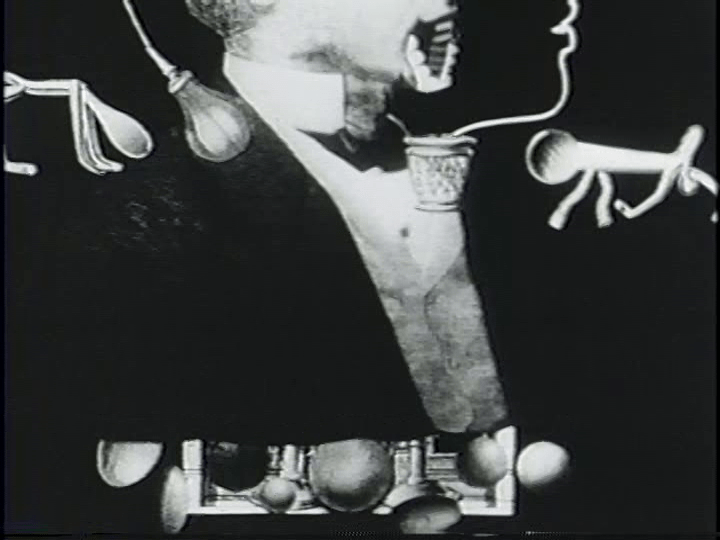

This causes her to rise to heaven, where she becomes fragmented:

He spends much of the rest of the movie attempting to put her back together again, but “does not succeed until after they are eaten by the giant head of a man (Max Muller), and they are descending to earth in an elevator”:

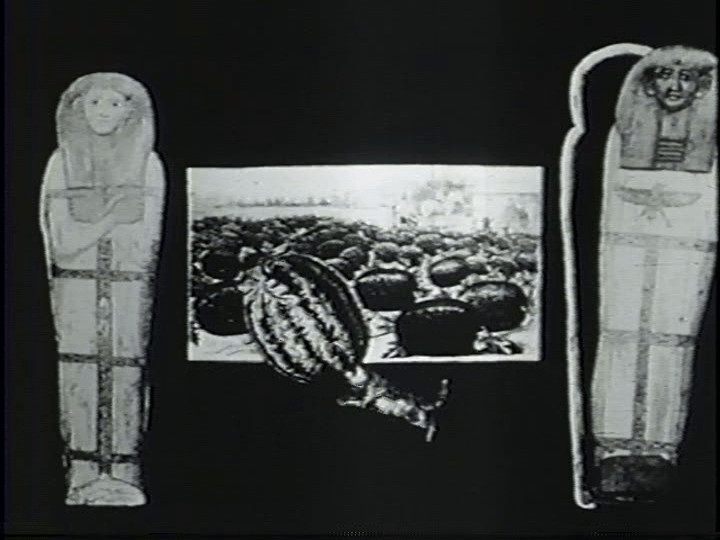

This narrative absolutely is discernable upon repeat viewings, and Heaven and Earth Magic easily lends itself to a variety of interpretations as well. Scholar Noël Carroll, for instance, reads it as a “mimesis of the drug experience” and a “metaphor of cinema as mind.” The viewer does need to put some effort into it, though, which lends credence to Sitney’s claim that Heaven and Earth Magic is Harry Smith’s “most ambitious and difficult work.” Whether or not you enjoy this film is utterly dependent on how interesting you find its images and musique concrète score. Apparently Smith preferred an original cut which was more than four times as long, but I think it’s just about perfect at 66 minutes. The use of what Carroll calls “literalization” is consistently surprising and hilarious, such as when the theft of the watermelon is accompanied by the sound of water:

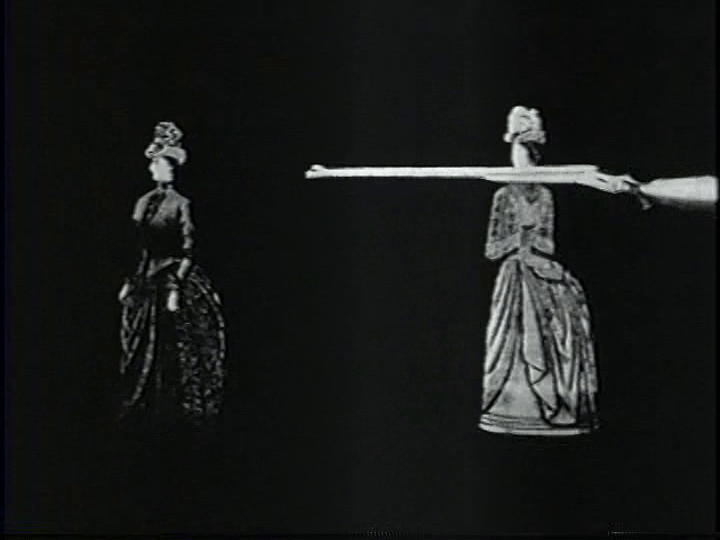

As is the doggedness (pun very much intended) with which these Victorian ladies pursue the thief:

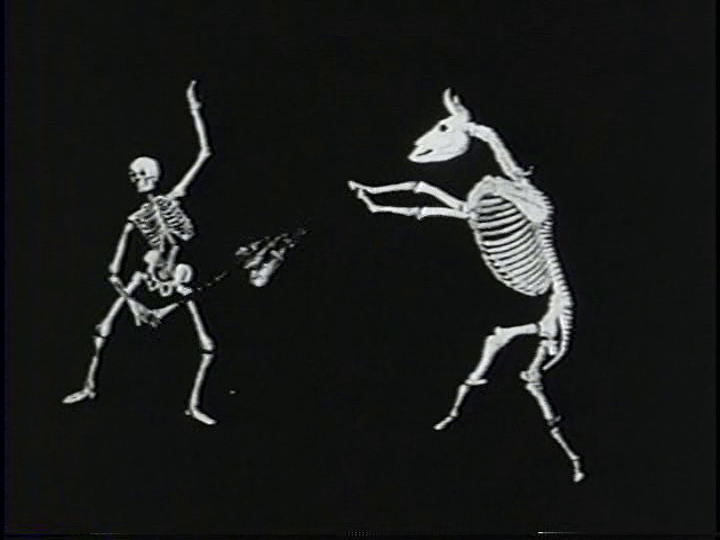

These dancing skeletons remind me of my oldest daughter’s equine phase, which included a brief but intense fascination with a Nature mini-series called “Equus: Story of the Horse”:

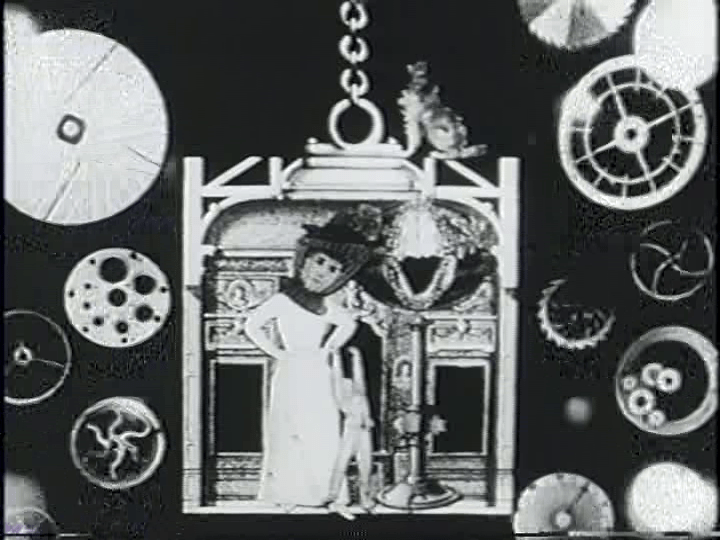

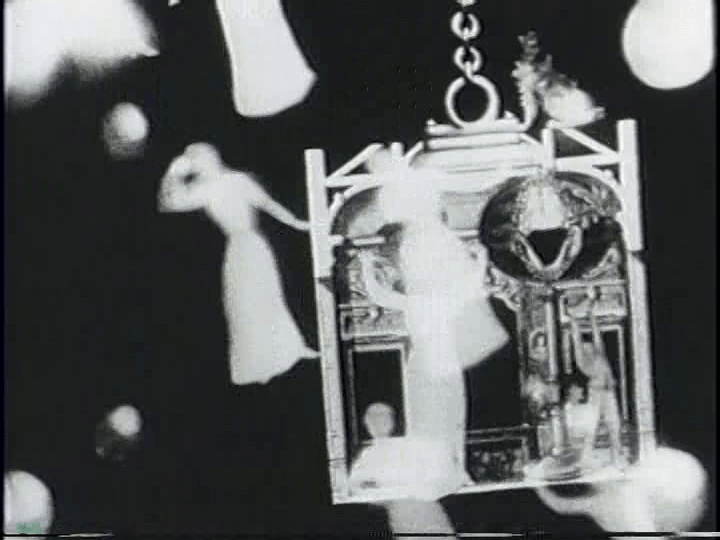

I love these wild phantasmic images which appear later in the elevator sequence referenced above:

And the symmetry of Heaven and Earth Magic‘s final and first images, which mirror each other, is quite satisfying:

My Loving Wife (who has a graduate degree in art history) observed that Smith is an obvious influence on the animated sequences Terry Gilliam created forMonty Python’s Flying Circus and flagged this scene as her favorite:

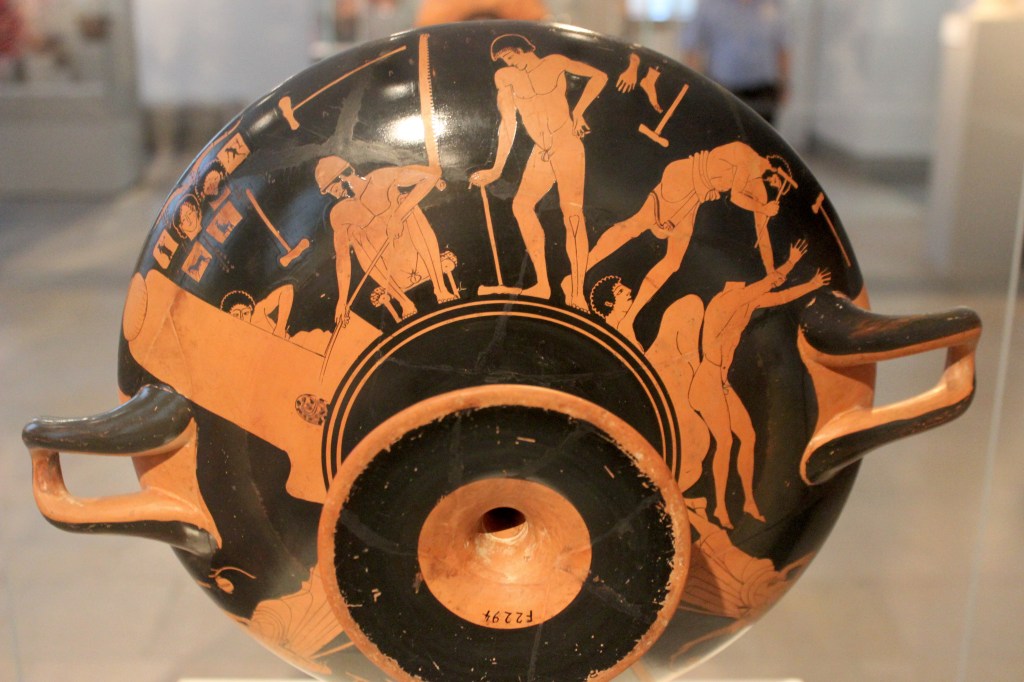

Because it reminded her of the Berlin Foundry Cup, which depicts a Athenian bronze workshop:

And this brings us to a second movie. You see, this is an example of red-figure vase painting, and that is precisely what the negative photography in Maya Deren’s The Very Eye of Night has always made me think of! Considering the facts that with its 15-minute runtime, this film plus Heaven and Earth Magic are roughly the same length as a short feature, and that both are frequently lumped together as examples of avant-garde/experimental/underground cinema, this struck me as a perfect opportunity for a double feature. So here’s a picture of my Kino Lorber/Re:Voir DVD release of The Maya Deren Collection:

Although The Very Eye of Night (like Heaven and Earth Magic) does not appear to be currently on commercial streaming video platforms, some people may have access to it via Kanopy through a license paid for by their local academic or public library.

In an article about the film, scholar Elinor Cleghorn refers to The Very Eye of Night as Maya Deren’s “most technically complex and medium-specific film” and clearly establishes that it was regarded as a major work during its initial screenings in 1959. The titles of recent appreciations by Ok Hee Jeong (“Reflections on Maya Deren’s Forgotten Film, The Very Eye of Night“) and Harmony Bench (“Cinematography, choreography and cultural influence: rethinking Maya Deren’s The Very Eye of Night“) demonstrate that it is not thought of as such today, which Cleghorn attributes to our friend P. Adams Sitney, who was otherwise a champion of Deren but dismissive of this film, which he felt represented an unwise divergence from “the powerful element of psycho-drama” that he prized in her earlier work.

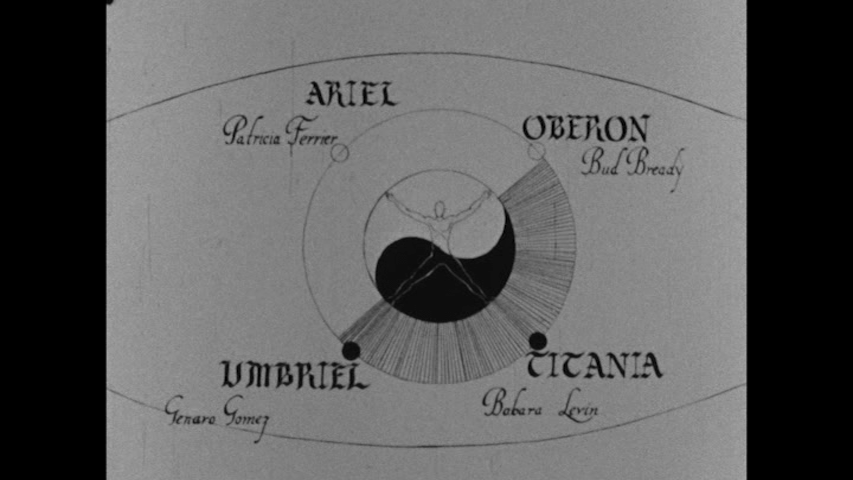

The Very Eye of Night is similar to Heaven and Earth Magic in that it has an elaborate story that can probably only be followed by viewers who know what to look for. As described by scholar Sarah Keller in her book Maya Deren: Incomplete Control, it begins with an elaborate credit sequence which introduces the characters and “upholds the philosophical, mythical, and/or metaphysical principles espoused by the film as a whole,” as in the case of this image which references an eye with an iris, the yin-and-yang symbol, and Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man”:

It is more than a minute after the final title card before the first dancers (Richard Englund as Uranus and Rosemary Williams as Urania) appear, arcing across a field of stars accompanied by music by Deren’s future husband Teiji Ito:

Doubling/mirroring proliferates throughout the film, not just in the way the dancers are paired with one another:

But also through costume elements such as the tights worn by the actors who portray Gemini (Don Freisinger and Richard Sandifer):

And this ribbon:

The most enchanting images for me are the ensemble shots:

But the entire film has a timeless quality which supports Deren’s statement of purpose which was originally published in Film Culture magazine and reprinted in the book Essential Deren: Collected Writings on Film: “whether or not the viewer formulates it, I am convinced that he will know that I am proposing that day life and night life are as negatives of each other, and that he will feel the presence of Destiny in the imperturbable logics of the night sky and in the irrevocable, interdependent patterns of gravitational orbits.” In an essay called “‘The Eye for Magic’: Maya and Méliès” published in Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde, scholar Lucy Fischer argues that “for Deren the sky was a site of rapture” and that “just as outer space presents a field in which earthly laws are violated and superseded, so the domain of film dance liberates the body through the magic of cinematography and editing.” I think something of this mindset can be seen in the triumphant gesture which concludes the dancing:

It is fair to observe that The Very Eye of Night is not as rigorous as Heaven and Earth Magic, but to my eyes it’s also more beautiful, and I don’t consistently prefer one over the other. Meanwhile, both are perfect fits thematically and visually for a night associated with transformation, mystery, and experimentation. I’d actually suggest watching them in reverse order of how they’re discussed in this post, staring with The Very Eye of Night as an accompaniment to your Corpse Reviver #2 and saving Heaven and Earth Magic for after trick-or-treating is over. You’ll probably be hungry, which brings me to my final recommendation: this recipe for beef chili with beans. Author Grant Achatz notes that it’s a modified version of the one his mother made for him and his cousins every Halloween. We gave it a try a couple of years ago and have been making it annually ever since. Although Achatz says he ate it at the beginning of the evening “as a way to counteract the sugar buzz to come,” we prefer to save it for after we return home both as a way to warm up from a usually cold (and sometimes rainy) night outside and a strategy for breaking up our kids’ candy consumption. It’s hard to make chili look good, but here’s a picture of the pot which is now hanging out in our freezer awaiting its big night anyway:

Definitely don’t skimp on the ancho and pasilla powders, which you can easily make yourself as far in advance as you want by toasting seeded and stemmed dried chilies, letting them cool, and then grinding them. We usually grind our own beef as well, but that’s nowhere near as essential. The recipe itself doesn’t mention them, but serving them with sour cream and cilantro as shown in the picture in Food & Wine is a great move.

And there you have it, a ready-made itinerary for your upcoming All Hallow’s Eve festivities!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.