As a kid who liked school, I’ve always been fond of September. Now as a higher ed lifer, the part of it I look forward to most is Labor Day. The fall semester of every college and university I’ve ever worked at has started during the last or penultimate week of August, and the holiday long weekend is a perfectly-positioned opportunity to recover from those frantic first few days. Although we currently live hundreds of miles from the nearest ocean, the beach remains the best place to spend it in my book, hence this month’s Drink & a Movie selections. The Last Wave (get it?) is a film which has loomed large in my memory ever since I saw it as an undergraduate film studies major at the University of Pittsburgh, while the White Negroni Daiquiri was created by bartender Mary White at The Lobo in Sydney, Australia where that movie is set. Here’s how we make it:

1 oz. White rum (Clairin Communal)

1 oz. Lemon juice

1/2 oz. Suze

1/2 oz. Lillet Blanc

2 tsps. Simple syrup

3 dashes orange bitters (Fee Brothers West Indian)

Shake all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled coupe glass. Garnish with a triangle-shaped lemon twist.

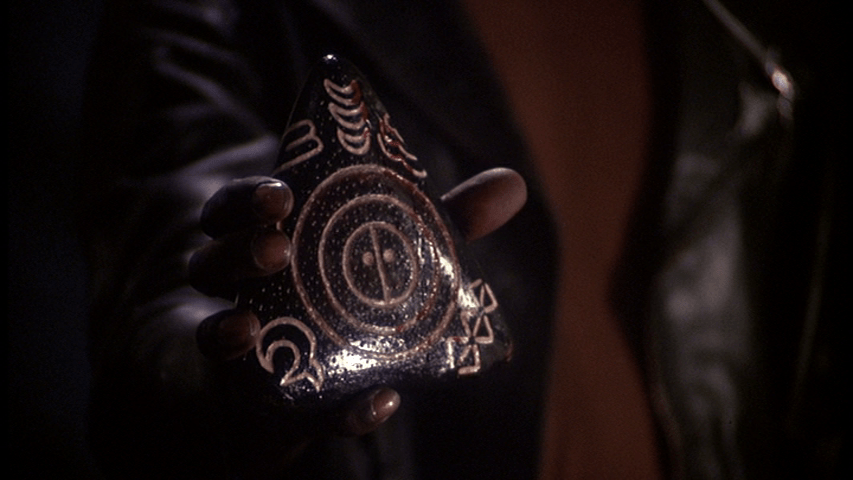

I can’t remember whether I first came across this drink in Imbibe, which simply calls for “white rum,” or in Australian Bartender, which specifies Bacardi Carta Blanca; meanwhile, the Lobo’s website currently lists Plantation 3 Stars as an ingredient. The latter two would both make a fine cocktail, but Clairin Communal, which blends distillates from four Haitian villages, caught my eye on recent trip to Ithaca establishment The Cellar d’Or and I think it works brilliantly here. The nose is intense and led me to expect Cachaça-level funkiness, but it’s remarkably smooth and thus lends complexity and intrigue without changing the essential character of the drink. Speaking of which: it is bracing thanks to the Suze, but goes down easy thanks to the Lillet, and has a relatively low ABV courtesy the 50:50 ratio of base spirit to fortified wine and liqueur, making it an ideal beachside sipper. Finally, as anyone who has already seen The Last Wave no doubt realized, the triangle-shaped garnish is meant to evoke this prop from the film:

It also contrasts nicely with the square base of the glass we chose, yeah? Which, by the way: like most of the glassware we’ve been featuring this year, My Loving Wife found this at Finger Lakes ReUse. Anyway, here’s a picture of my Criterion Collection DVD release of The Last Wave:

It can be streamed via the Criterion Channel or Max with a subscription as well or via most other major commercial streaming video platforms for a rental fee.

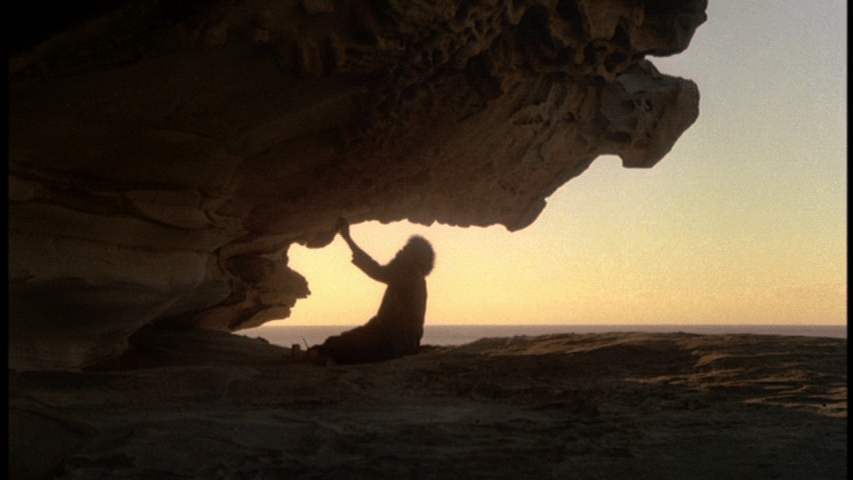

In a review included in 5001 Nights at the Movies, critic Pauline Kael insightfully notes that the plot of The Last Wave “is a throwback to the B-movies of the 30s and early 40s, and the dialogue–by the young director Peter Weir and his two co-scriptwriters, Tony Morphett and Peter Popescu, is vintage R K O and Universal.” More importantly, as Kael continues, Weir “knows how to create an allusive, ominous atmosphere.” This starts with the film’s first image of an Aboriginal Australian man who we will come to know as Charlie (Nandjiwarra Amagula) painting signs on a rock outcropping :

A dissolve creates the impression of one of them looming over the outback community where the next scene is set:

Two Aboriginal children walk toward the camera down a dusty road:

As they reach an elder, he stands up and gestures at the sky:

Cut back to the road, which momentarily changes color:

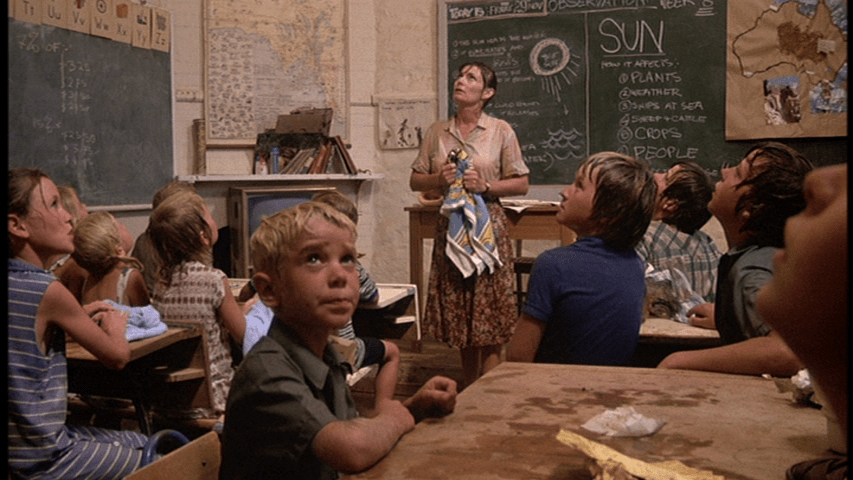

Cut to a group of white children playing cricket in a schoolyard:

Although the sky is virtually cloud-free, there is a clap of thunder followed by a sudden torrential downpour. The children’s teacher (Penny Leach) hustles them inside. Suddenly, they hear the sound of hail on the roof of the school:

A giant ball of ice crashes through the window, bloodying a student:

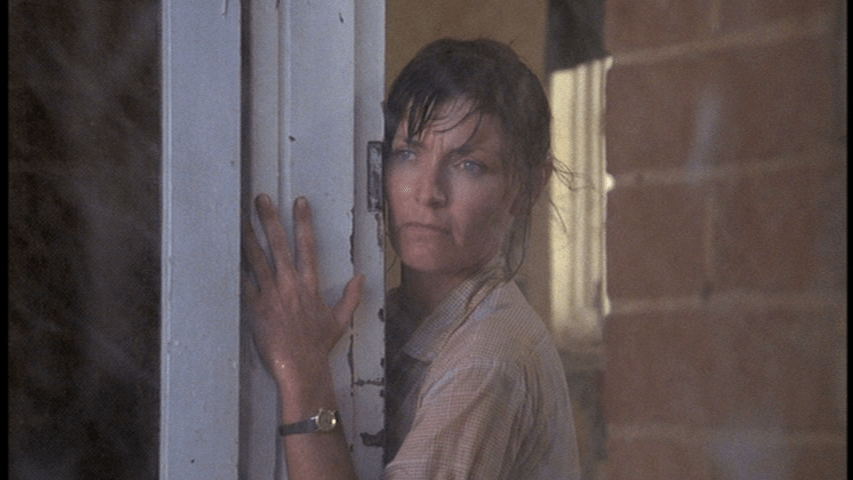

The scene ends with the teacher contemplating the scene outside as the storm ends as abruptly as it started:

Cut to a strange rainbow over Sydney, where the rest of the film takes place:

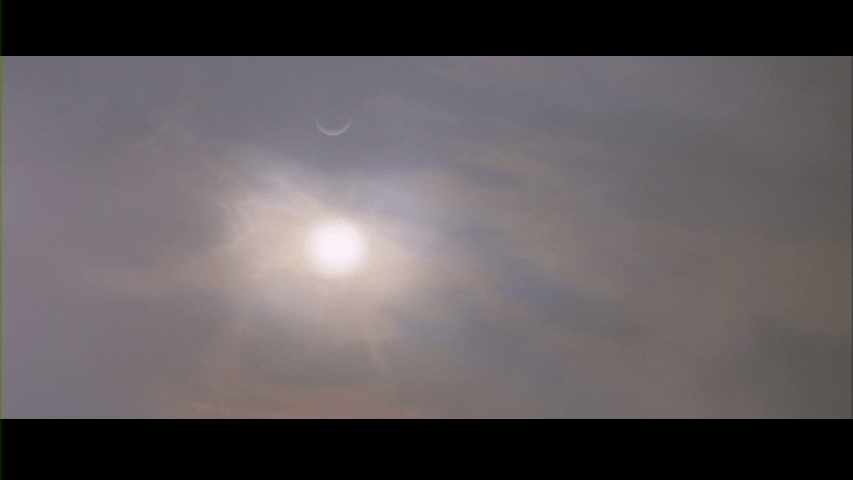

Which reminds me of the functionally-similar crescent moon omen from Prince of Darkness:

Kael’s review skews negative: she calls it “hokum without the fun of hokum” because “the occult manifestations are linked to the white Australians’ guilt over their treatment of the aborigines.” Like scholar Jerod Ra’Del Hollyfield, I believe she’s missing the point somewhat. The subject of The Last Wave isn’t guilt, but rather anxiety over what Hollyfield describes in a chapter about the film for the book Postcolonial Film: History, Empire, Resistance as “the problems inherent in any attempt at reconciliation between Aboriginal and white Australian culture.” He notes that Weir bookends the narrative of lawyer protagonist David Burton (Richard Chamberlain) with images of water “demonstrating the limits of systems such as pipes to control nature.” Scholar Michael Bliss also discusses the film’s water images, which I personally find quite fun, in Dreams Within a Dream: The Films of Peter Weir, arguing that they “have a virtually surrealistic force.” Here’s one of my favorites:

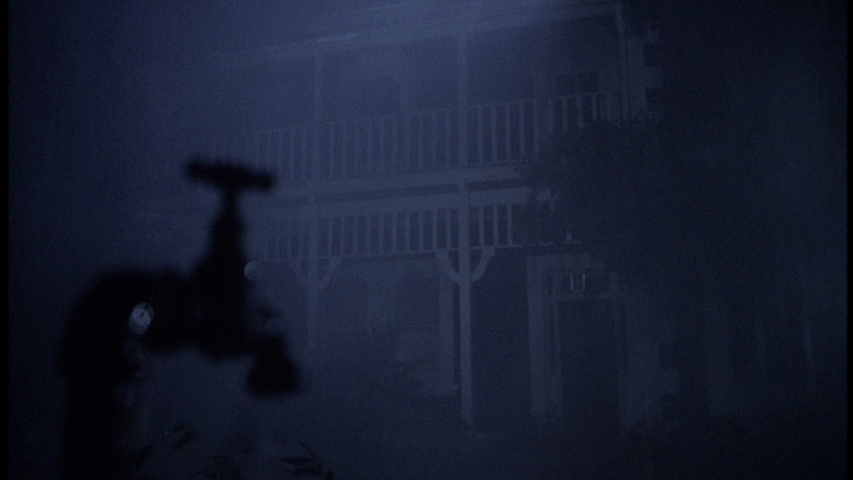

Per Bliss, this “absurd and contradictory” shot “succinctly communicates the tension between the spigot (a man-made object meant to restrain or divert water) and a natural force, the rain, that is simultaneously available in its unrestrained form.” Or take this faucet outside David’s house:

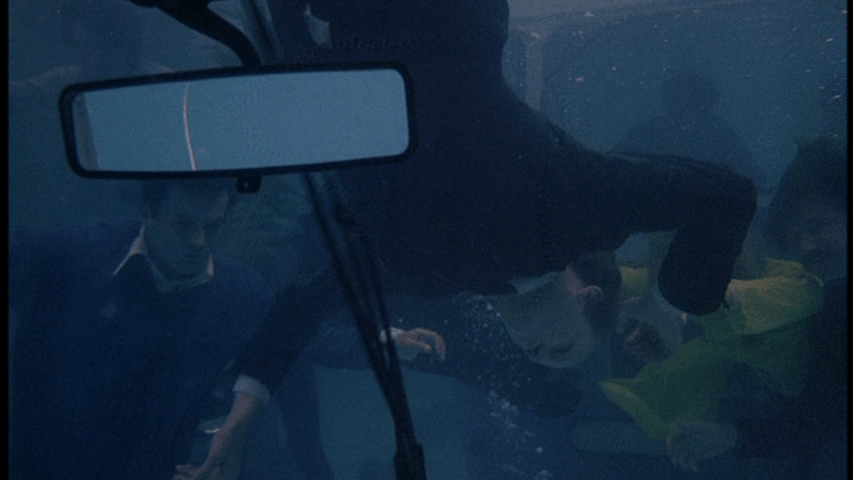

Bliss argues that it foreshadows “the eventual conflict between white civilization and natural phenomena that is one of the film’s primary concerns” because it drips: “this man-made bulwark against water’s pressures cannot stop the force of the water any more than the flimsy awareness of David’s conscious mind can prevent the repeated intrusion of visionary episodes.” I’d be tempted to call this reading overdetermined were it not for the fact that this shot appears twice. Speaking of visionary episodes, here’s one in which water pours into David’s car through the radio:

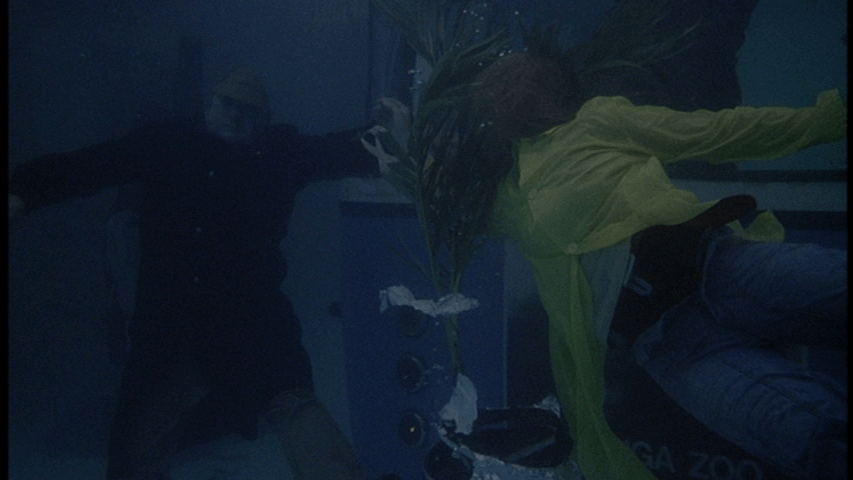

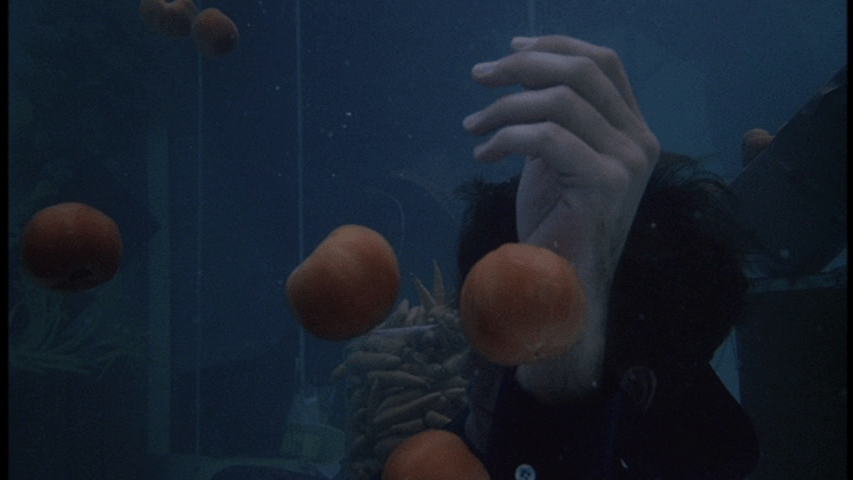

He looks up from this to find that the people he saw outside his windshield a moment before are suddenly submerged:

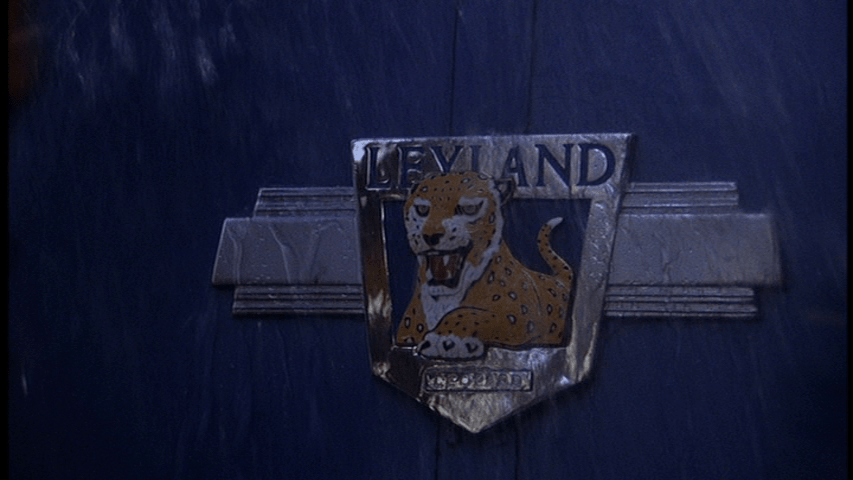

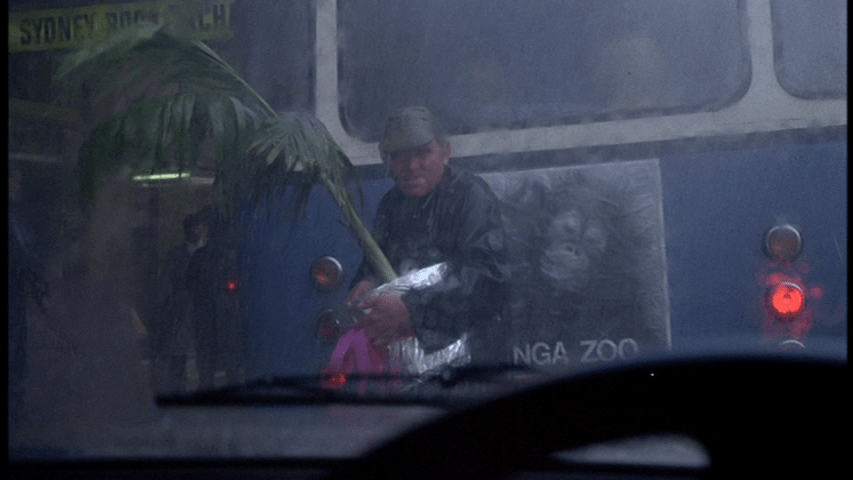

The man with the palm in the middle image actually appeared much earlier in the film carrying the same plant. I appreciate Bliss’s comments about the pictures of animals which adorn the bus in this scene, a leopard and a chimpanzee:

One of the ways that Weir maintains a successful ambiguity in the film is by concentrating on action and images that at first seem to have nothing to do with the story. At one point, Weir zooms in on a British Leland car, only vaguely intimating that there is some connection between the leopard on the car’s logo and the film’s story. The car logo, as well as the bus poster for the [Taronga] Zoo, which features two chimpanzees, not only demonstrates how white society appropriates the power and significance of animals and turns them to commercial account but also highlights the society’s use of natural images as nothing more than superficial signs instead of meaningful symbols.

This is a big part of what Chris (David Gulpilil), an Aboriginal man David defends in court against a charge of murder, is talking about when he says to him, “you don’t know what dreams are anymore.” This in turn becomes the primary cause of David’s fear that he is failing to apprehend something important, which drives him as mad as a Val Lewton heroine. This manifests most clearly in a confrontation between David and his pastor stepfather (Frederick Parlow) after David loses his case when Chris chooses to incriminate himself instead of revealing the secrets of his tribe:

REV. BURTON: You lost the case, but you haven’t lost the world.

DAVID: Haven’t I? I’ve lost the world I thought I had. The world where what you just said meant anything. Why didn’t you tell me there were mysteries?

REV. BURTON: David, my whole life has been about a mystery.

DAVID: No! You stood in that church and explained them away!

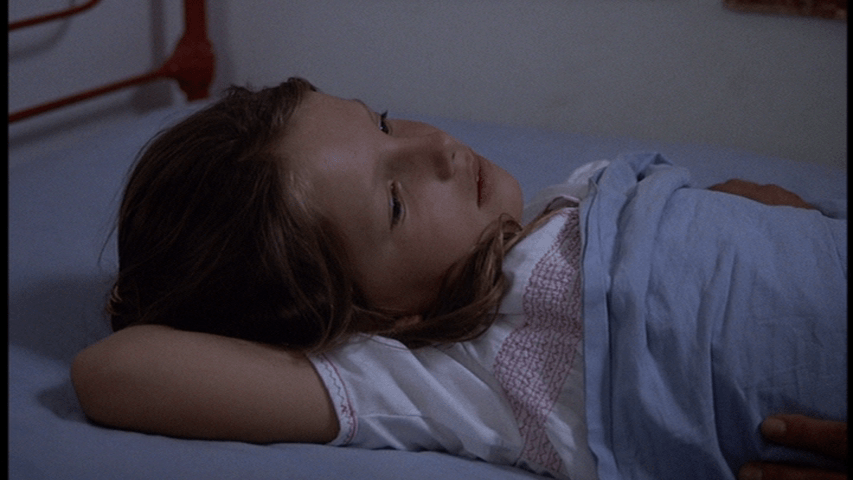

In an essay astonishingly written at the ripe old age of 19, Australian critic Adrian Martin identifies “the suggestion is that children are closer to the marvellous, and have a potentially keener perception of it – that is, before the adult world socialises it out of them forever” as a key motif in The Last Wave, citing David’s daughter Grace’s (Ingrid Weir, real-life daughter of director Peter) interpretation of a vivid dream she had as being about Jesus as an example.

This, to me, is the slam-dunk argument against the idea that the film is preoccupied by liberal guilt. If it were, we might have expected David to channel his angst into making sure his children grew up with a better sense of the history of the land they live on than him or his wife, a self-described “fourth-generation Australian” who had never met an Aboriginal before Chris and Charlie join them for dinner in the film. Instead, because he is egocentric, he convinces himself that he has been chosen to save his people from destruction.

In a conversation with Tom Ryan and Brian McFarlane published in Peter Weir: Interviews, Weir admits to being dissatisfied with The Last Wave‘s ending, and I agree that it’s the weakest part of the film. This absolutely does not extend to the final shot, though! There’s a time and place for Hollywood-style special effects, but this isn’t it: give me a screen full of color and motion every time!

I love this sequence of shots which precedes the fall of a “black rain” that a newspaper headline will later suggest was caused by pollution for similar reasons:

This is the same kind of economical filmmaking that I applauded when I wrote about Hester Street last September. And that brings me back to the White Negroni Daiquiri. Although I consumed the ones I made while writing this in my back yard, I felt like I was at the beach. Hopefully this pairing will transport you to Australia, with no need to purchase an airplane ticket or gas!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.