My favorite cocktails are generally the ones that taste the best to me. This might not seem like such a revelatory statement, but appearance and aroma are also huge parts of a beverage’s appeal, and since this blog’s primary focus is on film, a visual medium, you might think that the former in particular would be just as big a factor in determining which ones I feature on it. While My Loving Wife and I have spent more and more time thinking about glassware, garnishes, and how we stage our photographs, though, all of this decision-making usually follows our selection of what to include in our Drink & a Movie series. But there are exceptions. The brilliant hue of the Yellow Cocktail immediately made me think of the word “Technicolor,” which led me to Suspiria in short order last October. This month’s pairing also started with the drink.

The Aviation was one of my first favorite classic cocktails, probably in large part because The PDT Cocktail Book is organized in alphabetical order. But Jim Meehan’s accurate description of it as “azure-colored” also played a role: it absolutely does remind me of the sky! My research for this post led me back to Hugo R. Ensslin’s Recipes For Mixed Drinks, where a recipe for the Aviation was first published. Unlike most pre-prohibition tomes, his begins with a guide to measures; unfortunately, it indicates that a “pony” equals a “jigger,” which doesn’t make a lick of sense and therefore is of little help in figuring out what he means when he says that one of either is also equivalent to “1/4 whiskey glass” and two (i.e. “1/2 whiskey glass”) make one “drink.” Luckily, the Aviation’s proportions of 2/3 gin to 1/3 lemon juice plus two dashes each of Maraschino and crême de violette closely resemble those of Ensslin’s Manhattan: 2/3 whiskey, 1/3 sweet Italian vermouth, and two dashes of Angostura bitters. These are of course the very proportions most bartenders use today. If we assume that Ensslin’s drink should also contain about three ounces of spirits, we can work backwards and determine that his Aviation calls for two ounces of gin and one of lemon juice.

Setting aside a second the fact that this cannot possibly taste balanced to anyone (we tried it and it’s every bit as overbearingly tart as you’d assume), we can at least make an educated guess what the original Aviation looked like. Using David Wondrich’s recommendation to interpret one “dash” of liqueur as being approximately equivalent to 2/3 of a teaspoon per two ounces of base spirit, Ensslin’s concoction can be assumed to have contained 10 parts clear (gin + Maraschino) and 4.5 parts cloudy (lemon juice) ingredients to one part purple (the crême de violette), or a 14.5:1 ratio of non-purple to purple components. Many updated versions of this drink either omit the crême de violette (a trend which began with a mistake or editorial decision in Harry Craddock’s influential Savoy Cocktail Book) or contain so much of it that the resulting mixture more closely resembles that ingredient’s namesake flower than any shade of sky I’ve ever seen. This is not true of Ensslin’s recipe, though, or the one in PDT that I originally fell in love with, which consists of 10 parts clear and three parts cloudy ingredients to one part purple. Wondrich’s own Aviation recipe calls for 1/2 ounce of lemon juice and 1 1/2 teaspoons of Maraschino, which conveniently equates to 1/4 ounce. He only uses one teaspoon of crême de violette, but if we scale this up just a smidge to 1/4 ounce we end up with a drink that contains nine parts clear and two parts cloudy ingredients to one part purple or an 11:1 ratio of non-purple to purple ingredients, which in’t too far apart from Ensslin’s. And it tastes great! So here, then, is how we make an Aviation:

2 ozs. Gin (Aviation)

1/2 oz. Lemon juice

1/4 oz. Maraschino liqueur

1/4 oz. Crême de violette (Rothman & Winter)

Shake all ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled Nick & Nora glass. No garnish.

Hugo Ensslin specifically calls for El Bart gin, which only recently resumed production and which I’ve never seen in the United States, but Aviation gin was created with this cocktail in mind and is “clean and balanced and not too intense” like Wondrich calls for in his tweets, so it’s perfect here. The result is a balanced drink which is floral but not at all to the point of tasting like “fancy hand soap.” Beautiful and delicious!

The movie I’m choosing to go with it features the purest depictions of aviation as a means to escape the surly bonds of quotidian reality that I’ve ever seen, Ukrainian director Larisa Shepitko’s Wings. Here’s a picture of my Criterion Collection Eclipse Series DVD release of the film:

It can also be streamed via the Criterion Channel with a subscription, and some people may have access to it via Kanopy via a license paid for by their local academic or public library as well.

Wings begins with a strikingly layered composition:

Which is revealed to be even more complex than it first appears when a tailor emerges in the foreground:

The opening shot is succeeded by a title sequence (which it may be interesting to compare to Tár) consisting of a series of close-ups which critic Dave Kehr reads as depicting the film’s protagonist Nadezhda Petrukhina (Maya Bulgakova) “being fitted with a straitjacket, a garment that will leave her no room to spread the wings that war had given her.”

She was a fighter pilot during the Great Patriotic War but now works as the administrator of a vocational school and serves on Sevastopol’s city council. Despite her lofty position she is demonized by her students:

Can’t go into a restaurant after 6pm without an escort because she’s a woman:

And is generally out of synch with post-Stalin Soviet “Thaw” society:

Meanwhile, she is prone to staring off into space and dreaming of flying, which is depicted each time via a two-shot combination of a close-up of Petrukhina followed by aerial footage accompanied by the film’s wistful main theme:

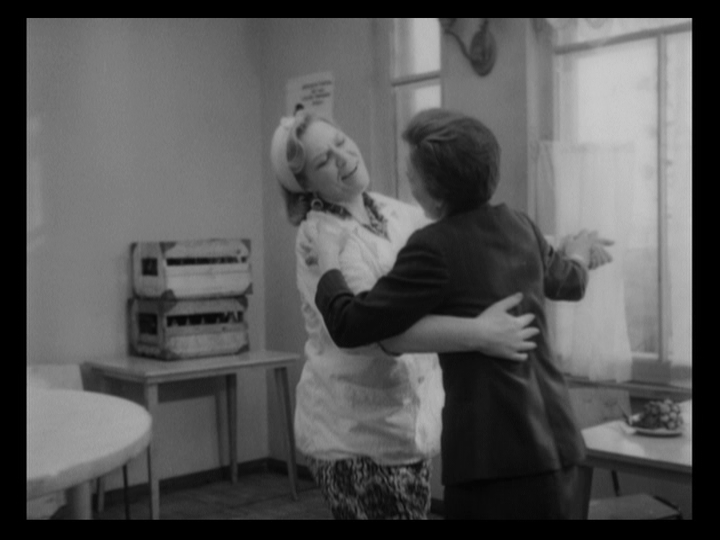

Gender is definitely a contributing factor to Petrukhina’s sense of alienation. A rare interlude in which she and a café owner named Shura (Rimma Markova) allow themselves the luxury of reminiscing about their school days and wind up waltzing together ends with them self-consciously realizing that a group of men is gawking at them through the window:

Or consider scholar Lilya Kaganovsky’s description of another key scene:

Nadezhda has no place to occupy in the patriarchal system that tries to reassert traditional and normative gender roles after decades of Stalinist reorganization. This is particularly evident in the concert hall scene, when Nadezhda volunteers to take a student’s place during a performance. The costumes are large Matryoshka dolls, but while all the other girls are neatly enclosed inside their doll costumes (which have both a front and a back, indeed are “seamless”), Nadezhda has to be supported by two boys as she awkwardly fits herself inside the largest doll. This doll has only a “front,” and the boys carry Nadezhda around the stage while she crouches inside waving her arms. The “donned armor of an alienating identity” is here represented as incomplete and “propped up” by the male. The boys offer Nadezhda’s “feminine” representation a scaffolding without which the illusion would collapse and be exposed for what it is: a dominant cultural fantasy resting on a phantasmatic support.

Scholar Anastasia Sorokina further notes that “Nadezhda” is “a name unique to women that means ‘hope,’ an irony lost on non-Russian speakers” which helps “shed light on Nadezhda’s alienation as a middle-aged female war veteran occupying a society in which she is no longer relevant” and that Matryoshka dolls are “a traditional symbol of motherhood” used here “in a sarcastic nod to Nadezhda’s lack of biological children and her inability to connect with her surrogates at home and at school.”

Of course, there’s a fine line between inability and unwillingness and some of this is undeniably her own fault. Petrukhina’s daughter Tanya (Zhanna Bolotova) doesn’t know she’s adopted, so this doesn’t explain why she’s estranged from her mother. The scene where the latter surprises her outsider her apartment complex with a bottle of wine and cake might, though. Petrukhina is there to finally meet her son-in-law Igor (Vladimir Gorelov), but whatever inclination we might feel to sympathize with her is quickly undermined by her stubborn insistence on guessing which of the people gathered in the living room is him. She chooses . . . poorly:

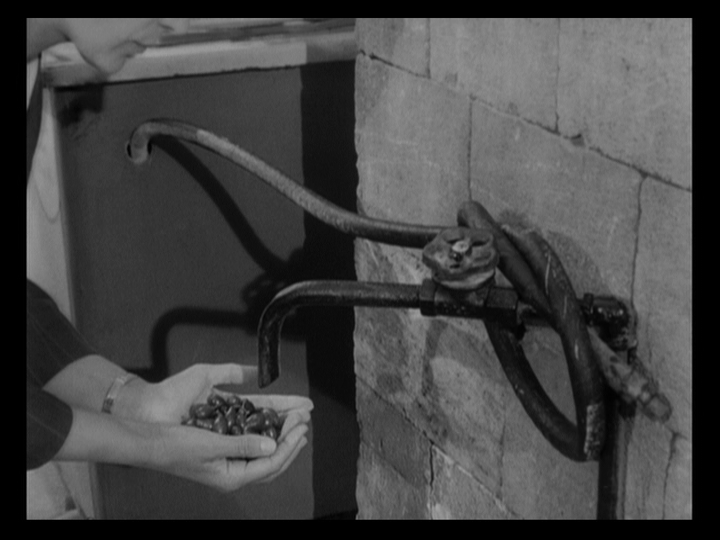

Embarrassed, she proceeds to exhort the assembled “young people” to cheer up and “play [their] boogie-woogie.” Oof! But underlying all of this is the trauma Petrukhina experienced during World War II, especially the moment when she watched her lover Mitya (Leonid Dyachkov) die in a fiery crash, which brings us to the film’s controversial ending and back to the reason I chose to write about Wings in relation to the Aviation. Mitya appears for the first time in the final third of the film following Petrukhina’s purchase of handful of cherries from a street vendor.

She attempts to run them under a faucet, but it doesn’t work:

Just that moment it starts to rain. Petrukhina holds the cherries up to be washed:

As everyone around her scatters:

She beholds the empty street:

And the camera tilts up to a white sky:

Suddenly we behold a lone figure running through a forest. We hear Petrukhina’s voice say “Mitya.” As the figure materializes into a man, we realize it’s a POV shot. He sits down next to Petrukhina. As he turns to look at her, the image freezes:

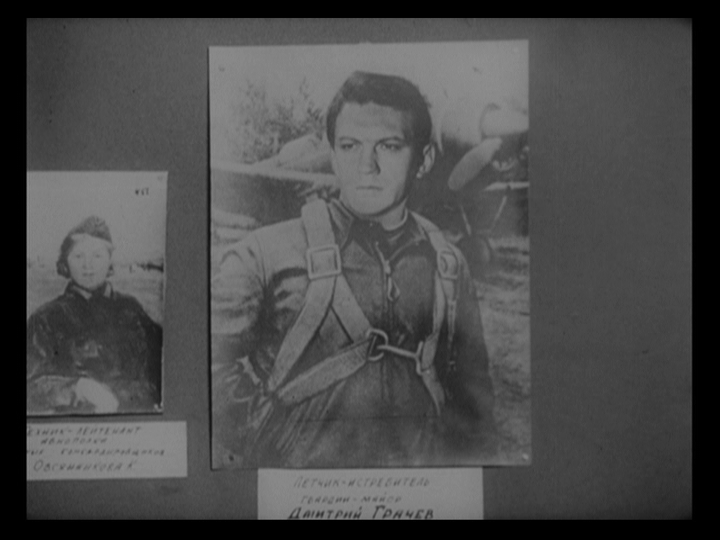

This is followed by four more freeze frames, all on shots of Mitya. The following scene finds Petrukhina visiting the museum directed by her friend Pasha (Panteleymon Krymov) where there’s an exhibit devoted to Mitya which she figures in as one of his apprentices:

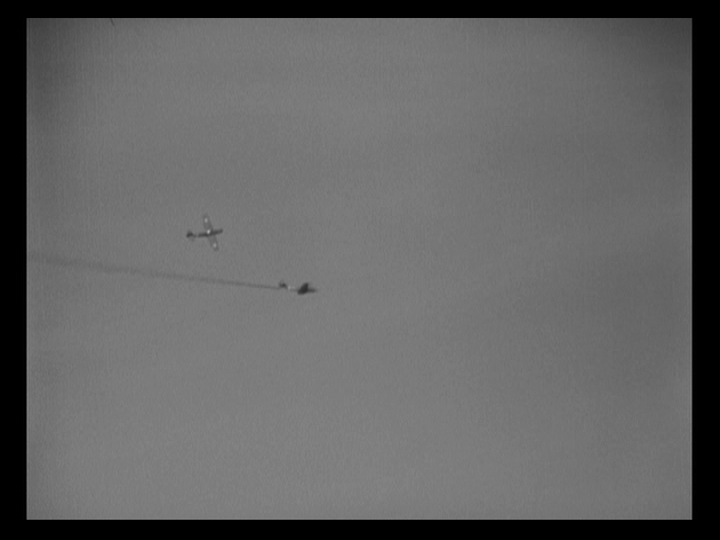

Cut to aerial footage of a plane:

Followed by a close-up of Petrukhina flying another craft:

She tries to talk to Mitya over the radio, but there’s no response. She attempts a maneuver to revive him, but his plane continues to trail smoke, and all she can do is fly next to him as he plummets to the ground:

There is one final freeze frame over a POV shot of his wrecked plane in flames on the ground:

Followed soon after by a shot of a photograph of Mitya which is part of the museum exhibit:

Which pans down to one of Petrukhina:

Pasha finally shows up and begins rambling on about scientists finding a mammoth frozen in the tundra, thawing it, and cooking its meat. Petrukhina interrupts him: “marry me,” she says.

When he doesn’t reply, she continues, “you don’t want to. Can’t you see it? The museum director marries one of his exhibits.” She wonders aloud if perhaps the woman pictured in the exhibit did die in the war after all and tells Pasha that she has quit her job at the school and is starting a new life. The next scene finds her watching children fly toy planes:

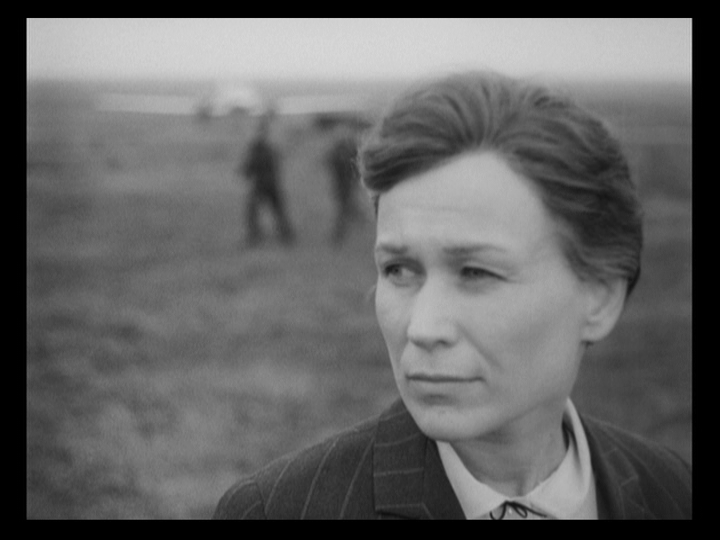

There’s an abrupt cut and suddenly she’s at an airfield:

It begins to rain. Petrukhina starts to seek shelter under the wing of a plane:

Then climbs into it:

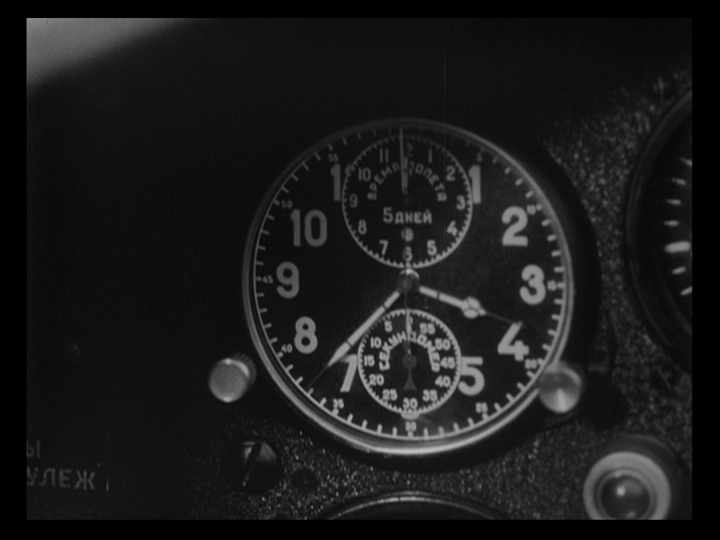

There’s a POV shot of the instruments followed by a close-up of Petrukhina smiling:

A group of pilots show up and decide to push her to the hangar in the plane so that she can “feel the wind in her face.” There’s a shot of her looking happy followed by one of her with a tear in her eye:

As the plane approaches the hangar, Petrukhina shakes her head no. Suddenly the plane starts up:

There is one last shot of Petrukhina:

Then the plane begins to taxi and as the pilots watch helplessly it takes off and disappears into the fog:

The film ends with two aerial shots followed by the end title. Scholar Åsne Ø. Høgetveit notes that this is most commonly interpreted as implying a suicide, but observes that throughout this scene Petrukhina’s facial expressions “change from nostalgic to insecure, determined, bold, happy, sad, melancholic, rebellious and victorious—quite an emotional roller coaster!” and that “[s]he does not seem like a defeated woman as she fires up the engine and takes off.” I agree. In fact, I was tempted to interpret the film’s conclusion as one more fantasy, only it begins and ends basically the same way as Petrukhina’s first visit to the airfield at the beginning of the movie. There, as Petrukhina leaves with her neighbor’s children, who she is babysitting, the camera racks focus to a close-up of a flower:

The final shot of Wings is, like this one, an image of hope. Høgetveit is not wrong that Petrukhina “takes off in what has got to be difficult flying conditions, keeping in mind the heavy fog on the airfield and the airplane model she has not flown before.” She might not land safely, and she will presumably be in a lot of trouble even if she does. But in Larisa Shepitko’s own words (as quoted by Høgetveit), she has also “come back to heaven, to herself, to her talent, to what she was born for, so to speak, because this is her natural vocation.” It’s an ending for dreamers, and the Aviation is the perfect drink to accompany it, so be sure to save some for the final reel!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.