My favorite thing in the whole entire universe, after my family, might just be the black raspberry bush growing in my back yard. It only produces fruit for a few weeks each summer, but those are some of the best days of the entire year because they begin with a harvest of berries that find their way into nearly every meal we eat during this time. They make terrific muffins and pies, are a brilliant addition to salads and yogurt parfait, and can even be converted into a wide range of savory condiments like barbeque sauce or salsa. They also go great in cocktails, of course! Raspberries freeze well, and thusly preserved can be made into tasty syrups all throughout the year, but my favorite way to use them is fresh off the vine in a modified version of the Knickerbocker in Dale DeGroff”s The Craft of the Cocktail. This drink, which DeGroff notes is adapted from Jerry Thomas, is emblematic of the fresh fruit-forward concoctions he and restauranteur Joe Baum championed it at New York City’s Rainbow Room in the 80s when nearly everyone else was relying exclusively on commercial mixes. Here’s how we make it:

2 ozs. Appleton Estate Signature rum

3/4 oz. Lemon juice

1/2 oz. Orange curaçao (Cointreau)

1/4 oz. Honey syrup

10-12 black raspberries

Lemon wedge

Muddle 7-9 raspberries with the lemon juice and curaçao in a mixing glass. Add ice and rum. Squeeze the lemon wedge into the glass, drop it in, shake well, and double strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with three fresh berries on a pick.

Appleton Estate Signature is a workhorse rum that’s perfect here because it isn’t showy and this drink is all about the berries; if you have another go-to for mixing, I’m sure it would work fine as well. DeGroff calls for 1/2 oz. raspberry syrup in lieu of fresh berries when they’re out of season, but our “blackcaps” are more tart than red raspberries, so we like to add a bit of 1:1 [water to] honey syrup to add sweetness even when they are. I’d normally reach for Pierre Ferrand Dry Curaçao in this situation, but it hasn’t been in stock in Ithaca the last few times I looked. Based on comparisons to the other orange liqueurs we do have on hand, though, Cointreau works just as well or possibly even better. Last but not least, we’ve tried this both with and without the lemon wedge, and it definitely is worth the extra step: versions that include it are discernably more complex than those without.

The movie I chose to pair with this showcase for upstate New York produce is famous Knicks fan Spike Lee’s underrated heist film Inside Man. Here’s a picture of my Universal Pictures Home Entertainment DVD release, which is suddenly a bit worse for wear after some recent shabby treatment by the baggage handlers at BWI airport:

It can also be streamed via Netflix with a subscription or most other major platforms for a rental fee.

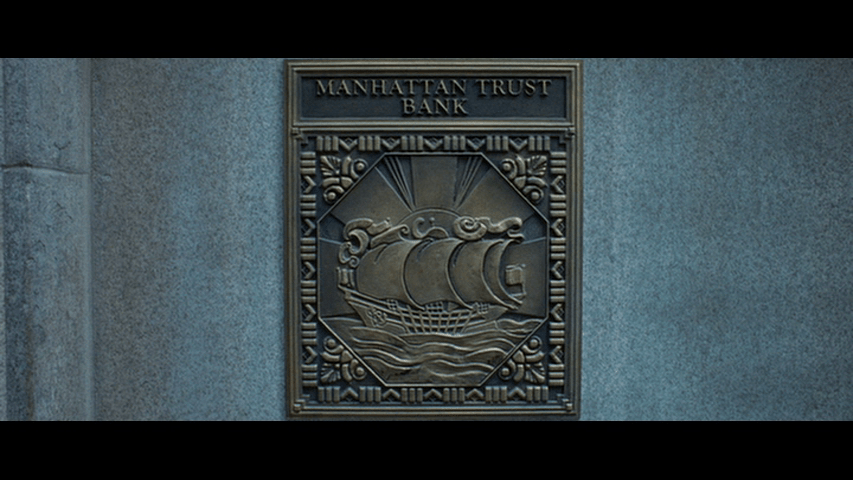

Inside Man opens with a credit sequence set to the song “Chaiyya Chaiyya” from the Indian film Dil Se. Contemporary reviewers mostly saw this as a nod to New York City’s multiculturalism, but with the benefit of hindsight it is obviously significant that the latter movie is an extremely political: it starts out like a simple love story, but ends with the protagonist blowing himself and the woman he is infatuated with up to prevent the latter from committing a suicide bombing. Similarly, although the beginning of Inside Man appears at first glance to consist of nothing more than a simple series of establishing shots, R. Colin Tait argues in Fight the Power! The Spike Lee Reader that it in fact is “confronting [viewers] with the early iconography of the financial origins of New York City” through images of ships:

“Gargoyles” (I believe this is actually technically a grotesque because it isn’t a waterspout):

And the New York Stock Exchange:

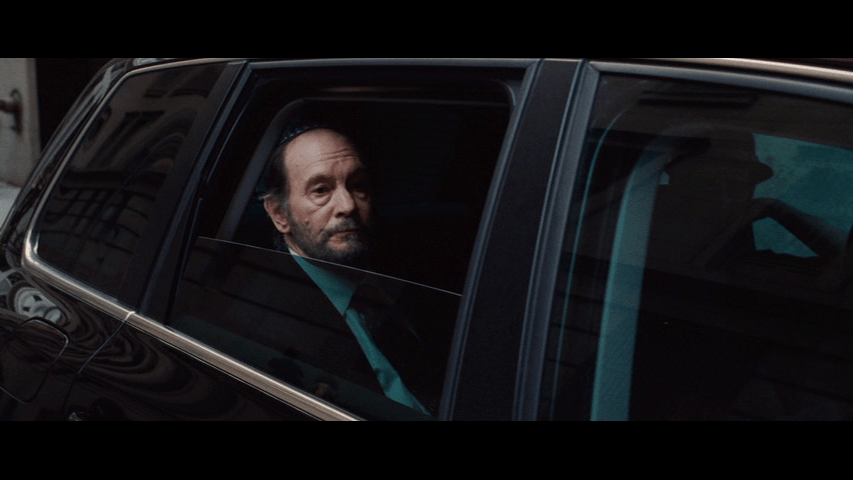

By the time it ends, we will have learned that one of the motives for the robbery that the film is about is to expose banker Arthur Chase (Christopher Plummer) as a war criminal who made his fortune by selling his friends out to the Nazis. In addition to making the film more interesting, this also provides an explanation for how Dalton Russell (Clive Owen) came to know about his target, safety deposit box 392, in the first place. After all, one of his accomplices (Bernard Rachelle) is a professor at Columbia Law who specializes in genocide, slave labor, and war reparation claims and who also has a nephew who is a jeweler.

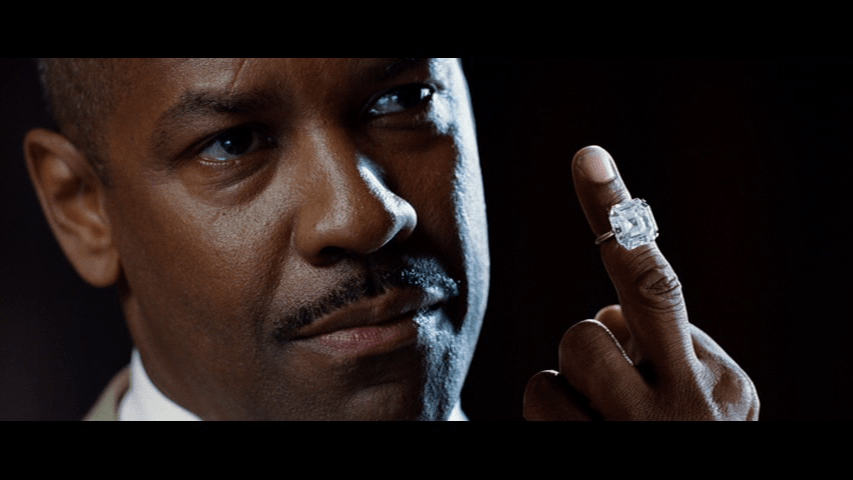

This seems like exactly the kind of person who might be able to track down a Cartier ring missing since the French Jewish family it belonged to was shipped off to concentration camps during World War II:

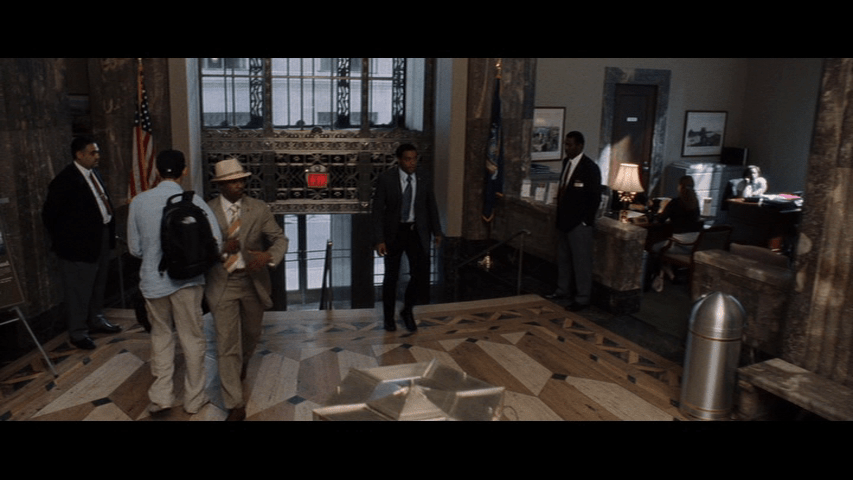

But this is all window dressing. What makes Inside Man noteworthy is the way Russell Gewirtz’s screenplay turns out to be an ideal showcase for Lee’s signature style and themes and performances by an outstanding cast led by Denzel Washington. His Detective Keith Frazier has great chemistry with his partner Bill Mitchell (Chiwetel Ejiofor) and its tons of fun to watch them riff off each other and Peter Gerety’s Captain Coughlin:

Frazier is also one of cinema’s great people managers, with a judo-like preference to let his adversaries and co-workers make the first move that works wonders on Willem Dafoe’s initially standoffish Captain John Darius:

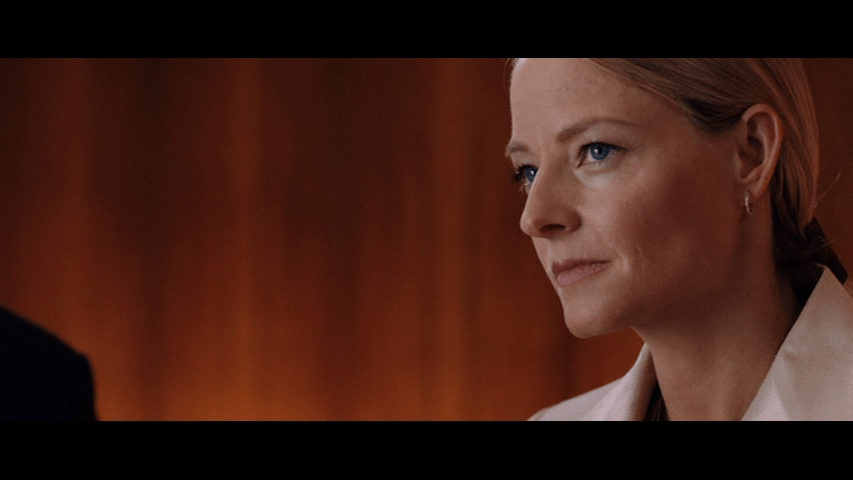

Jodie Foster’s stylish fixer Madeline White, whose condescending smiles turn to an icy stare when she realizes he has beaten her at her own game:

And even Russell, who secretly slips a diamond into his pocket as a token of gratitude (paid in advance) for bringing Case to justice and sign of respect:

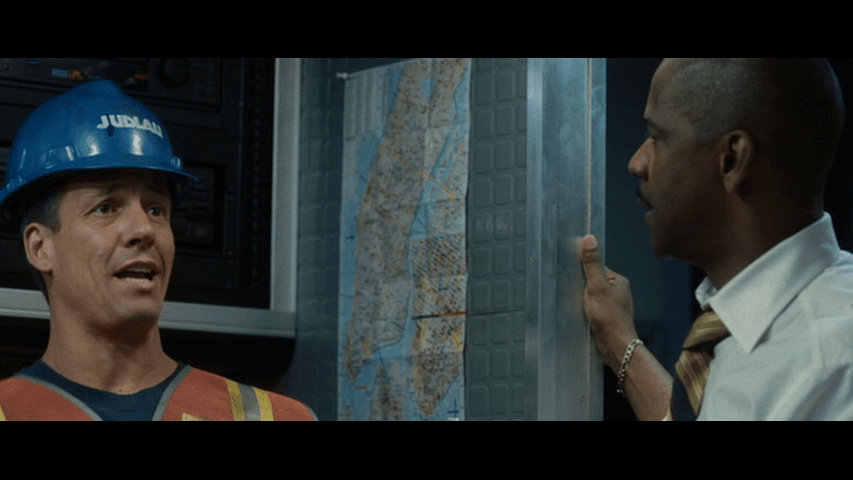

The dialogue is full of lines that might not have worked if other actors were reading them, but that I’ve been quoting regularly since 2006 because of how they sound in this film. My favorite belongs to Washington: “thank you, bank robber!” he replies when Russell tells him that if he and his girlfriend really love each other, money shouldn’t get in the way of them getting married. But the best example of what I mean might be Al Palagonia’s construction worker Kevin, who identifies the language being spoken in audio footage the cops record from inside the bank as being “100% Albanian.”

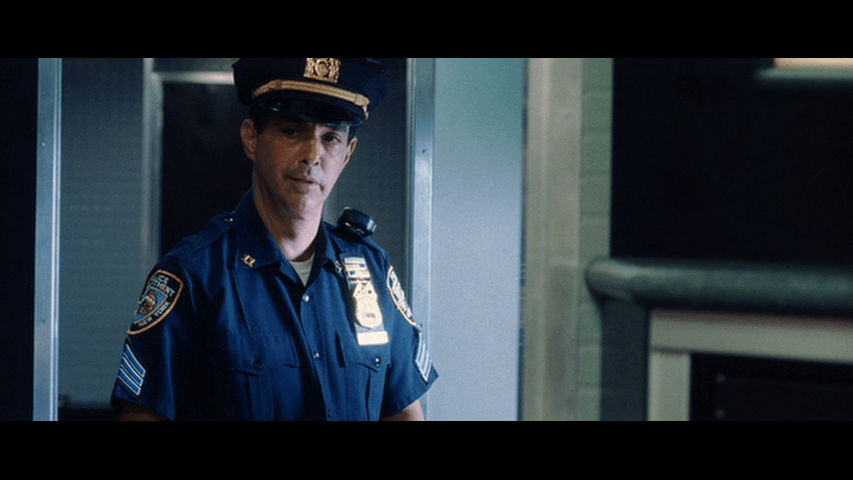

Neither really makes sense unless you’ve seen the film, but if you have they work beautifully in all manner of situations! Similarly, Inside Man features some wonderful reaction shots, including Captain Darius’s puzzled response “five bucks?” to a cryptic reference by Frazier to the “last time [he] had [his] Johnson pulled that good” and this look that Victor Colicchio’s Sergeant Collins gives everyone else in the Mobile Command Unit following a clueless comment from a not-yet-disgraced Arthur Chase, who thinks their only problem is that they can’t afford a jet:

Sergeant Collins, along with his fellow police officers, is also a vehicle for Lee’s typically nuanced treatment of racial tensions, here in a specifically post-9/11 America setting. They are all clearly competent and apparently decent, but their speech is nonetheless peppered with unequivocally racist language. Additionally, Lee adds a Sikh character named Vikram Walia (Waris Ahluwalia) to the film who wasn’t originally in Gewirtz’s script. “Oh, shit! A fucking Arab!” a SWAT team member shouts when he emerges from the bank with a note asking for food for the other hostages. Darius will later say “I don’t think you heard that” to him in a conversation that begins with Walia refusing to talk to the police until they return his turban, but ends with him laughing at a Mitchell’s joke that although he can’t go through airport security with being “randomly” selected for a security check, at least he can get a cab.

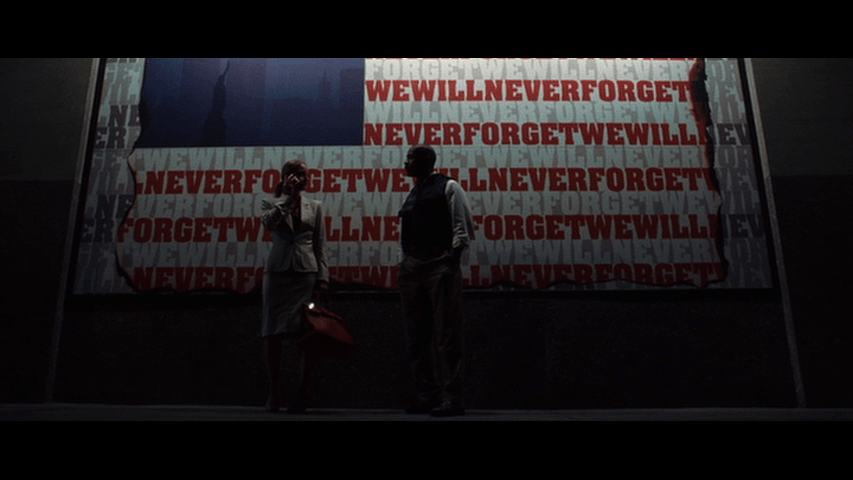

And stages a conversation between Frazier and White in front of this mural:

Lee is, I think, drawing a distinction between personal and institution racism. He doesn’t let people guilty of the former off the hook: Frazier calls Collins out for his “color commentary,” and I don’t doubt that Detective Mitchell really will help Walia file a formal complaint against the NYPD for the way they treated him. But Case walking around free is a bigger problem than any of this, and if even he must ultimately be held accountable for his misdeeds, it’s evidence that the long arc of the moral universe really does bend toward justice.

Inside Man also contains multiple examples of one of Spike Lee’s favorite techniques, whereby both the actor and camera are placed on a dolly to create the effect of a character gliding through space. In his book Rumble and Crash: Crises of Capitalism in Contemporary Film, Milo Sweedler describes the function of the first and last of the four such shots he catalogs, which depict Dalton Russell in his “prison cell,” as establishing and then confirming that “things are not what they appear to be in this movie, where appearances are perpetually deceiving”:

They also connect the character that most people who write about this film assume is the “inside man” of the title and Sweedler’s nomination, Arthur Case, who gets the double dolly treatment during a scene in which Russell describes his ruthlessly selfish actions during World War II to Madeleine White:

In his monograph Spike Lee, Todd McGowan suggests that this shot reveals that “what defines [Case] as a character–what gives him his singularity–is his act of profiteering on the Holocaust” and that “[n]othing can remove this singularity, not simply because of the horror of the act itself but because he continues to enjoy the monetary gains from it.” McGown also writes at length about the last remaining double dolly, which shows Detective Frazier moving toward the Manhattan Trust Bank following what he believes is the execution of a hostage:

Per McGowan, “Lee opts for the signature dolly shot here because Frazier’s anger separates him from his context. Though his anger is justified (unlike Case’s profiteering on the Holocaust), it nonetheless exceeds the context in which he is located. He can no longer act in the objective capacity of the negotiator but now has a passionate investment in the situation. His singularity at this moment comes to the fore.”

In other words, there’s much more to Inside Man than meets the eye! In this respect it’s actually quite different from the Knickerbocker, which is very much a case of what you see is what you get. But contrast is a perfectly legitimate basis for a pairing, and the main thing here is that the two together constitute a fine way to spend a warm summer evening. Like the carefully-adjusted hat that Detective Frazier wears:

Which casts a perfect Sam Spade shadow:

They’re cool. Ya dig?

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka my loving wife. Links to all of the entries in this series can be found here.