Ten years ago (wow that makes me feel old!) I emailed myself a link to a recipe by Rachel Tepper for a cocktail called the Sweet New Year. Serious Eats appears to have removed it (and many others, including most tragically this one for pasta with Meyer lemon and basil that we make for dinner at least once or twice a month) from their website at some point for unknown reasons, but thankfully the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine captured it for posterity in 2012. Here’s how you make this drink:

1 1/2 oz. Applejack (Cornelius)

1/2 oz. Bärenjäger

1/4 teaspoon Demerara sugar

Handful of mint

Muddle mint and sugar in a cocktail shaker. Add spirits and stir to combine. Strain into a chilled rocks glass and garnish with one nice-looking sprig of mint.

As described by Tepper, the Sweet New Year is a simple but elegant play on the traditional Rosh Hashanah dish of apples dipped in honey, which is the main reason I chose it for this month’s drink. It’s also a beautiful showcase for one of my favorite New York spirits, Harvest Spirits’ Cornelius Applejack, my current go-to host/hostess gift. I like the addition of mint, too, both for the complexity it contributes and because I can harvest it out of my own herb garden throughout late summer and early fall.

The movie I’m pairing this drink with is Joan Micklin Silver’s Hester Street. Here’s a picture of my copy of the Cohen Film Collection DVD release of the film:

Hester Street can also be streamed via Amazon Prime and Apple TV for a rental fee, and some people may have access to it through Kanopy via a license paid for by their local academic or public library as well.

Based on a novella by Abraham Cahan called Yekl (my library’s copy of which is available for free via the Internet Archive), the film tells the story of a family of Jewish immigrants living in New York’s Lower East Side in 1896. Steven Keats’s Jake (nee Yekl) is already living there when the story begins, enjoying the life of an apparent bachelor. This all changes when he sends for his wife Gitl (Carol Kane) and son Jossele (Paul Freedman) following the death of his father. Dismayed by their failure to embrace their new country as enthusiastically as he has, he begins neglecting them in favor of the people he had been keeping company with before they arrived, most notably a woman named Mamie (Dorrie Kavanaugh).

What I admire most about the film is the ingenuity on display in it. When people talk about “movie magic,” they’re often referring to things like huge sets, original costumes, intricate models, and armies of extras that Hollywood studios use to create whole worlds from scratch. Micklin Silver and company are wizards of a different sort: despite having access to few such resources, they nonetheless spin a convincing depiction of the nineteenth century out of locations, objects, and people readily available on the streets of 1970s New York. Call them alchemists. They understand that whether you are shooting an interior scene:

Or an exterior one:

The number of extras you have to work with is less important for creating a feeling of crowdedness than how well you fill the frame with them. You can also get a lot of mileage out of a well-placed reaction shot:

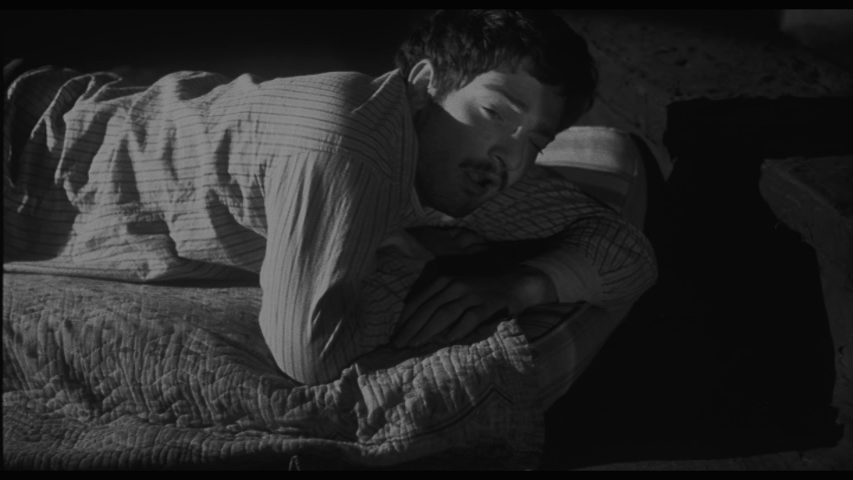

The only reason this sleepy fella is even in the picture is because Mamie and Jake need to ascend to the roof of Mamie’s building among the wash hanging out to dry for even a bit of privacy.

If you can so effectively establish the idea of a crowded tenement, are you really losing anything by not actually being able to show one? This scene is also a good example of another kind of economy–Silver and her editor Katherine Wenning cut away the INSTANT Jake’s lips touch Mamie’s.

What do they cut to? This close up of a sewing machine:

When you only have a limited number of period-authentic props to work with, you’ve got to make every second with them count! Similarly, when you don’t have the budget to recreate Ellis Island, you’ve got to use things like lighting and sound to create a sense of chaos and grandeur. I submit that the film does a fine job of this:

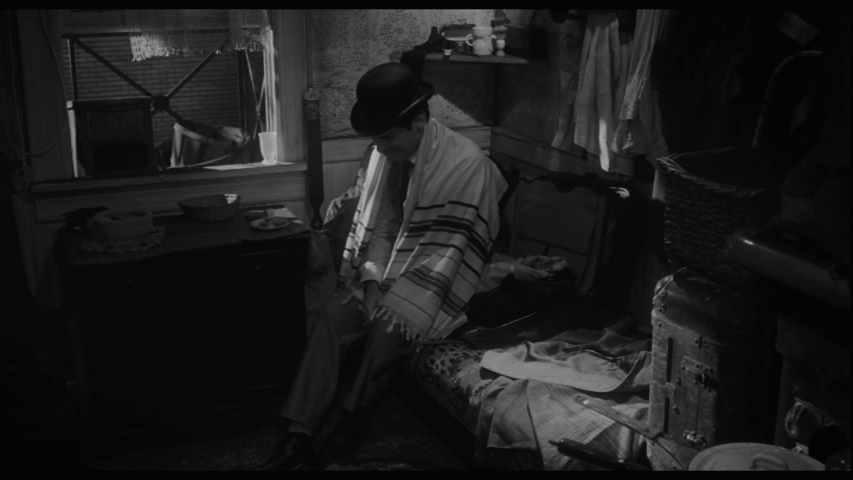

Hester Street isn’t perfect: most notably, I don’t think Keats and Silver succeed in showing us what’s going on inside Jake’s mind, which makes their version of the character much less interesting than Cahan’s. Whereas the novella describes him as being “in a flurry of joyous anticipation” on his way to meet Gitl and Jossele at Ellis Island, but then goes on to say that “his heart had sunk at the sight of his wife’s uncouth and un-American appearance,” the Jake of the film just seems put out by how much they’re crimping his style from the word go. It’s the difference between a man who wants to do the right thing but is so intoxicated by his ideal of America that he can’t and one who is just kind of a jerk. It also renders some scenes unintelligible, which Micklin Silver herself seems acknowledge in one case on the commentary track on my DVD copy of the film. She notes that this scene showing Jake awkwardly praying for his deceased father was meant to convey the idea that he’d never even gotten around to unpacking his tallit:

I think I see now how they’re trying to accomplish this by having Jake use the stylish bowler hat we saw him buy a few scenes earlier as a head covering and ending the scene with him expressing frustration:

I’m not sure I ever would have gotten there on my own, though, since you could also interpret this whole scene as just showing Jake grieving. Of course, Hester Street isn’t *about* Jake the same way Yekl is. The single best thing about Micklin Silver’s film is without doubt Carol Kane’s Oscar-nominated performance as Gitl. Whether she’s trying to make sense of her husband’s baffling decision to go out the night she arrives in America after more than three years apart from him:

Gleaning from a small, absent-minded gesture that her lodger Bernstein (Mel Howard, a non-professional actor who is also quite good here) is in love with her:

Realizing while watching him teach her son how to read that she returns his affection:

Or extracting a king’s ransom from the lawyer sent by Jake and Mamie to secure a divorce without ever saying a word:

She communicates deep wells of emotion with little more than subtle changes in expression. Especially when contrasted with the hammy antics of Steven Keats’s Jake, it’s a masterclass in minimalist acting.

Speaking of performances, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Doris Roberts’ entertaining turn as Jake and Gitl’s landlady Mrs. Kavarsky.

“You can’t pee up my back and make me thinks it’s rain!” she says at one point, and she spends the entire film embodying the essence of a person for whom this represents a philosophy of life.

Rosh Hashanah is never mentioned in either Hester Street or Yekl, but the way the former ends calls to mind the traditional wishes for a “sweet year” that the drink featured in this blog post is named after. The rabbi who presides over their divorce cautions Gitl that she must wait ninety full days before she remarries, but says to Jake, “you, young man, may wed even today if you desire.” A subsequent crane shot of him walking down the street with a veiled Mamie suggests he might well have done so! Although their conversation is all about how spending Mamie’s life savings to buy off Gitl has altered their plans for the future, it does end with a kiss and an embrace:

The next scene is the film’s last, and it depicts a parallel conversation between Gitl and Bernstein in which they talk about how they’ve invested that same sum of money in a grocery store that she will work in while he studies the Torah in the back.

I personally choose to believe both couples will be happy. Which: mazel tov!

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Other entries in this series can be found here.