This month’s Drink & a Movie post is dedicated to My Loving Wife Marion Penning, who you may know as the Official Photographer for this blog series. It is thanks to her that I now spend all year looking forward to the start of the Tour de France, a sporting event that I can’t recall ever having followed before we met. Which: what a loss for me! The first one we watched together was the 2013 edition. Marion, a longtime fan, patiently defined unfamiliar terminology like “domestique” and “peloton” and explained what the different colored jerseys all meant. When the 2014 Tour rolled around we were engaged, and she was in Canada getting the family cottage ready for our wedding reception the following month. Since we basically still didn’t have internet access there at the time, I considered it my solemn duty to update her on every twist and turn of Vincenzo Nibali’s road to victory via text message, and infamously ruined my future sister-in-law’s birthday dinner (to this day I don’t know why Marion didn’t mute her phone!) in the process. By the time Chris Froome took off for the top of Mont Ventoux on foot in 2016, I was officially hooked.

Marion’s favorite cocktail is the Negroni, so a few years ago I gave her a copy of Gary Regan’s book-length study of it for her birthday. Coincidentally, the best thing we’ve tried from it so far is a concoction named after the winner of the 1924 and 1925 Tours, Kevin Burke’s Bottecchia:

30 ml (1 oz) Fernet Branca

30 ml (1 oz) Cynar (Cynar 70)

30 ml (1 oz) Campari

1 small pinch kosher salt

1 fat grapefruit twist

Stir all ingredients in a mixing glass without ice until salt is dissolved. Add ice, stir , and strain into a chilled coupe. Squeeze the twist over the drink, then discard.

As described by Burke (Head Barman at Colt & Gray in Denver, Colorado at the time of publishing) in the book, this drink honors Ottavio Bottecchia, a known socialist whose “politics put him in unpopular company” and “whose life was cut short when he was found dead in 1927 of unknown causes.” He was also the first Italian ever to win the Tour de France, and his second victory was aided by Lucien Buysse, who Bottecchia’s Wikipedia entry identifies as the first domestique in Tour history.

Per Burke, the intent of substituting Fernet and Cynar for the Negroni’s gin and Campari is to “turn it up to 11.” My use of Cynar 70, a higher-proof version of the spirit, knocks it up yet another notch. With flavors this strong, the Bottecchia was never destined to be a drink for all palates, but I think Burke is right when he also notes that the salt tempers the bitterness of the other ingredients. This is, in fact, probably the most successful example of using salt as a cocktail ingredient that I’ve found so far.

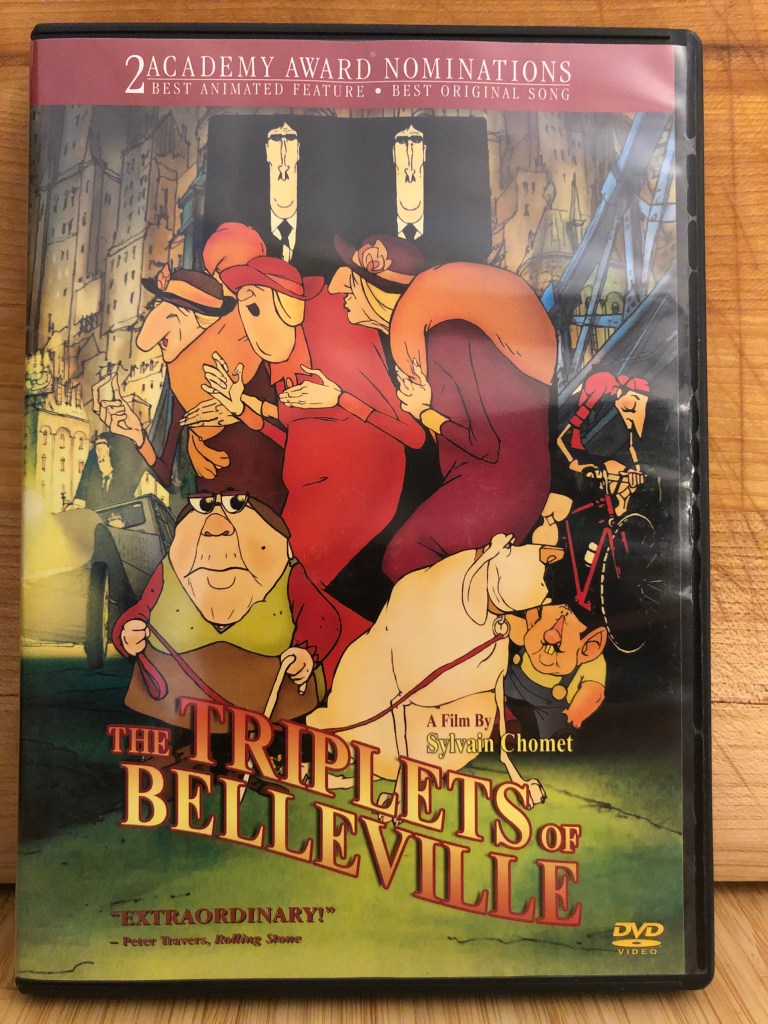

The movie I’m pairing with the Bottecchia is Sylvain Chomet’s The Triplets of Belleville. Pictured here is the Sony Pictures Classic DVD release I purchased from Amazon a few months ago:

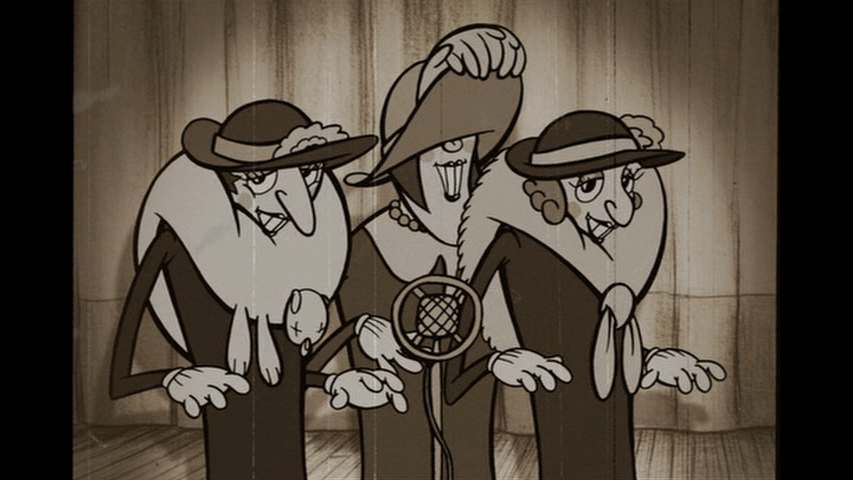

The film can also be streamed via Amazon Prime and Apple TV for a rental fee. The Triplets of Belleville opens with an animated one-reeler featuring the eponymous sisters singing an earworm called “Belleville Rendez-vous”.

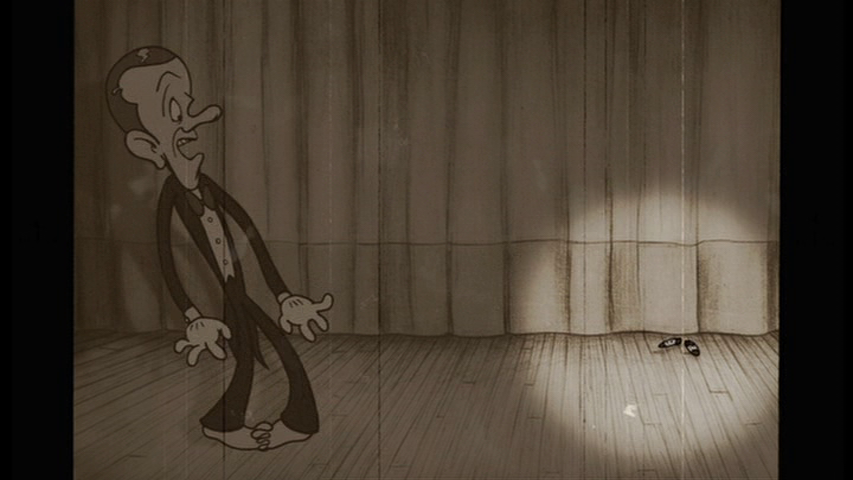

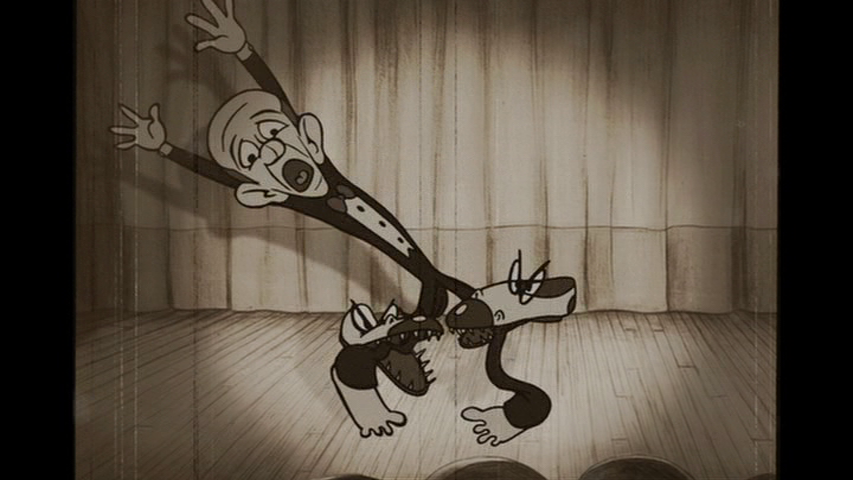

Their performance is part of a demented act that includes, among other things, a Fred Astaire lookalike who tap dances so hard that his shoes fly off, come to life, and devour him:

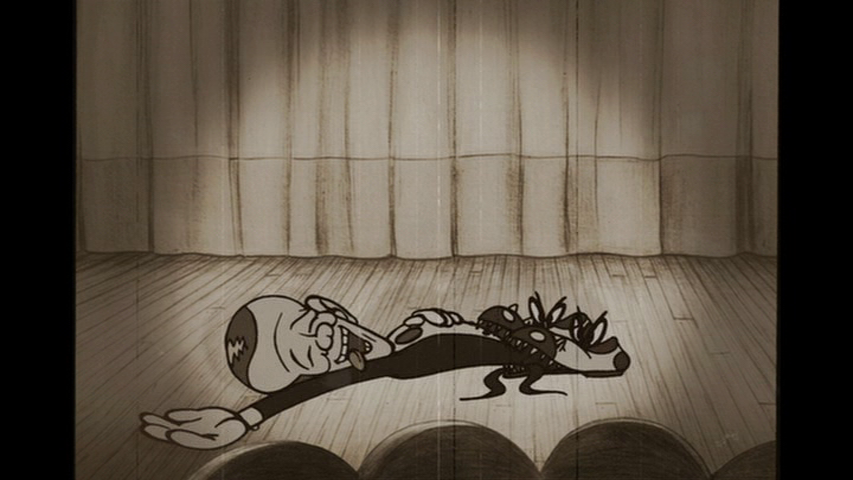

The sequence ends with the sepia tones of old celluloid dissolving into the grays of a mid-20th-century television set, which almost immediately loses reception:

The camera pulls back to reveal a boy and his grandmother, the heroes of our tale:

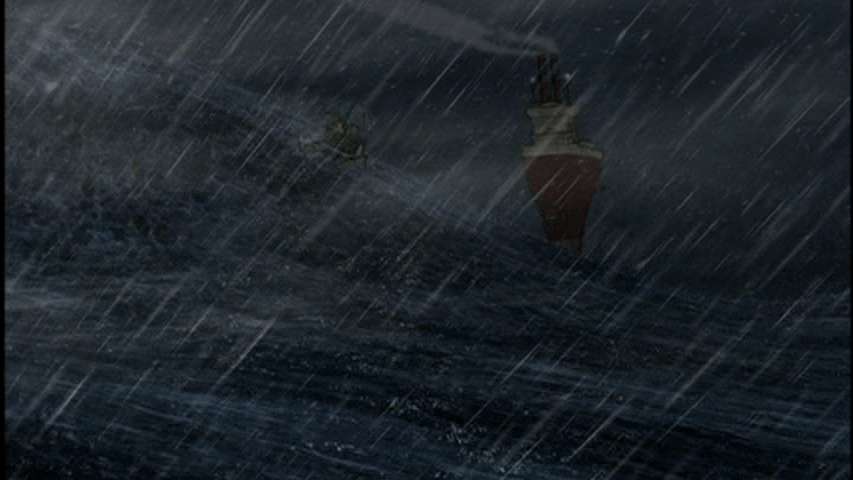

We soon learn that she will do anything for him, even if that means (in a sequence which artfully blends digital and hand-drawn animation) chasing an ocean liner through stormy seas in a paddle boat.

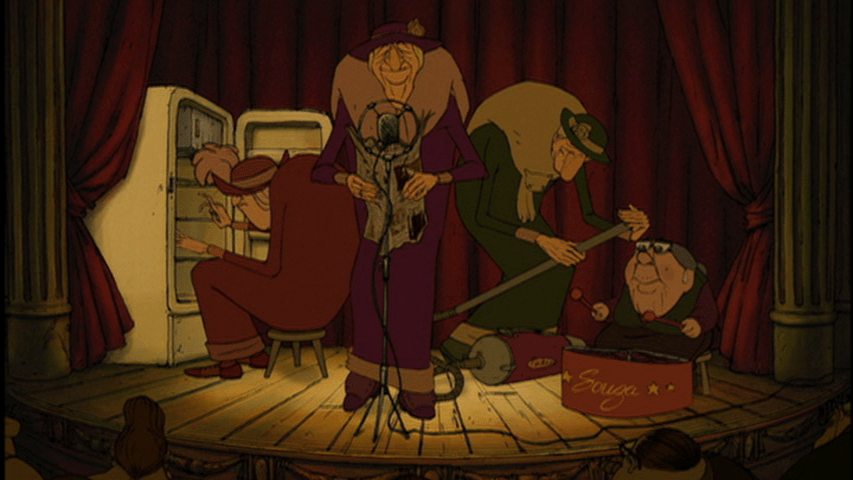

But that comes later, after the boy, whose name is Champion, has been kidnapped by French mobsters, The grandmother, whose name is Madame Souza, will pursue him to Belleville, where she’ll meet up with the triplets and join their ensemble, which now features improvised instruments made from household objects:

They’ll eventually rescue Champion after an extremely over-the-top chase, but before any of that happens, Madame Souza gives her grandson a puppy named Bruno:

Then she gifts him a tricycle:

The Triplets of Belleville features all sorts of delightful grotesqueries, including a frog-based tasting menu that ranks among the most memorable meals in movie history. My favorite, though, is what happens to Champion’s body after he receives this present. It isn’t just a thoughtful gesture, you see, but a raison d’être. When we see him again he’s training for the Tour de France:

Madame Souza is right behind him on the tricycle whistling a cadence:

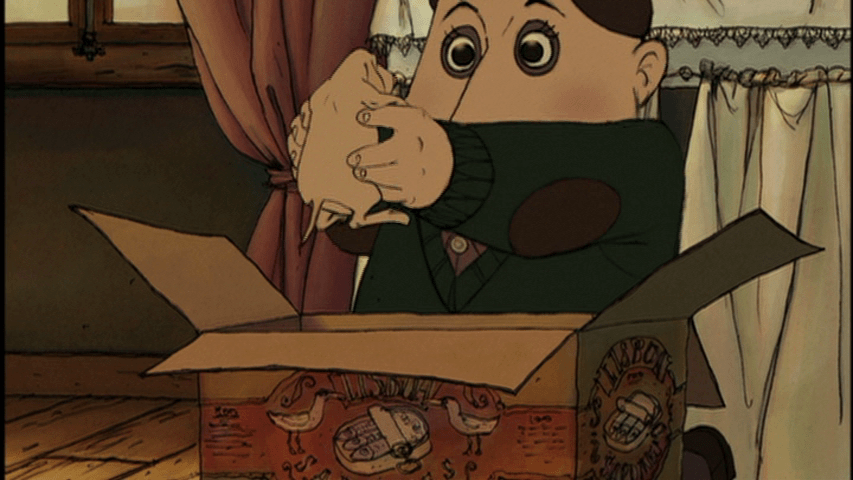

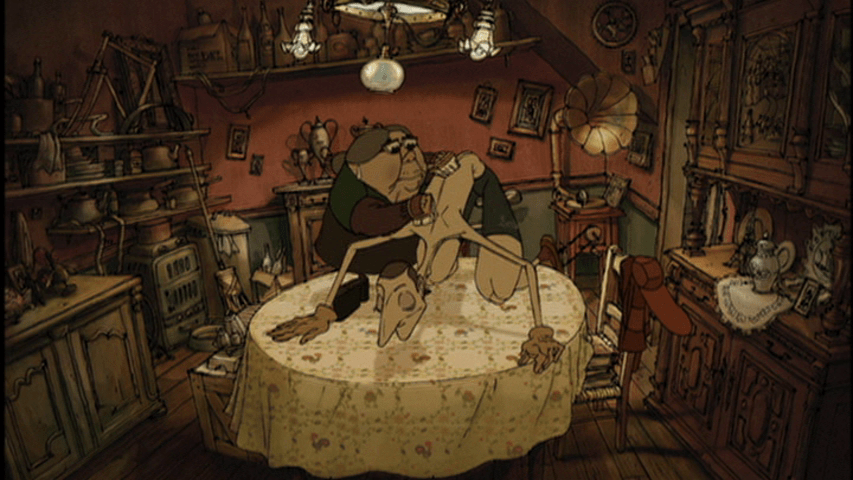

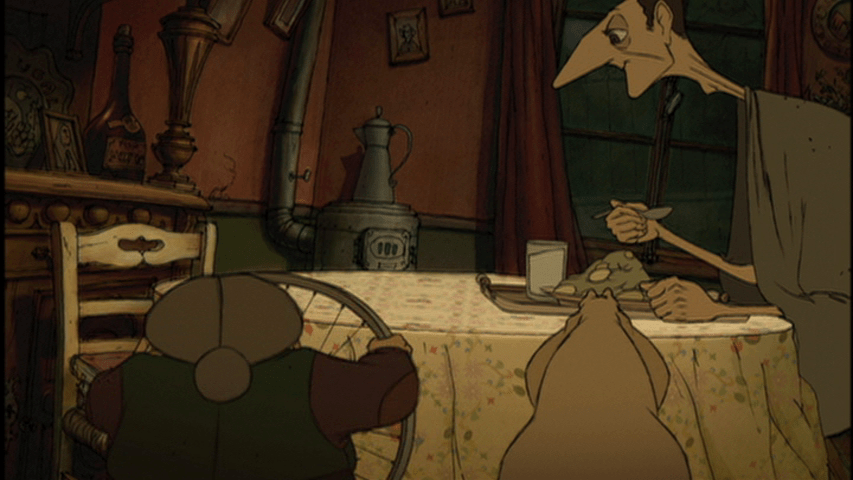

The scene which follows this is one the real prizes of the film. Champion, now rail thin with the exception of absurdly oversized leg muscles of a professional cyclist, staggers inside after his training ride:

He collapses on the dinner table and Madame Souza goes to work on his body. She attacks his calves with first a vacuum:

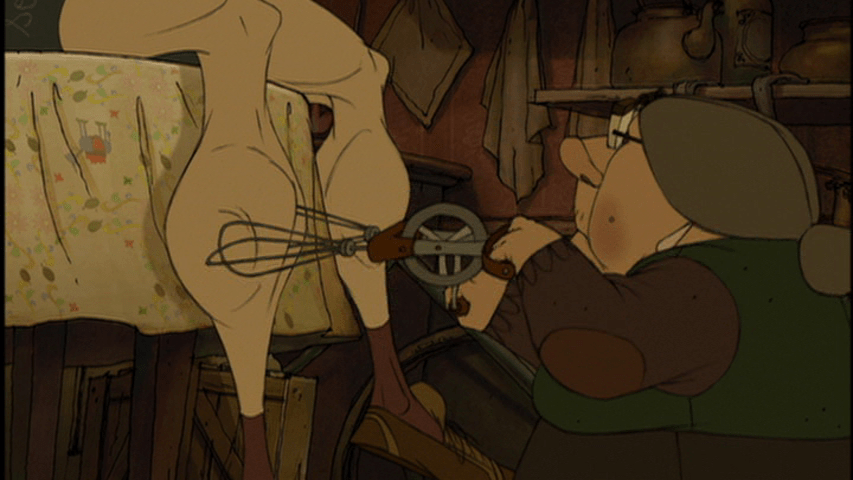

Then egg beaters:

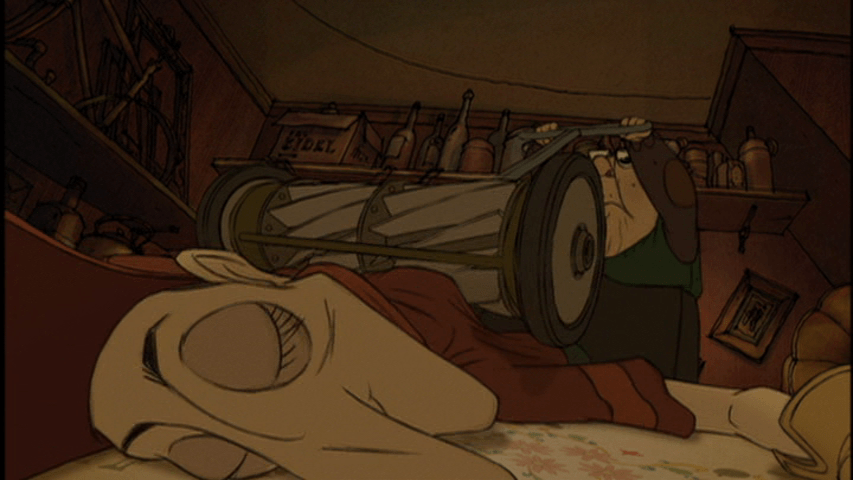

After that comes a lawnmower back massage and scrubbing brushes:

And then it’s time for dinner. While Champion eats, Madame Souza repairs his bike wheel using a tuning fork and a statue of the Eiffel Tower:

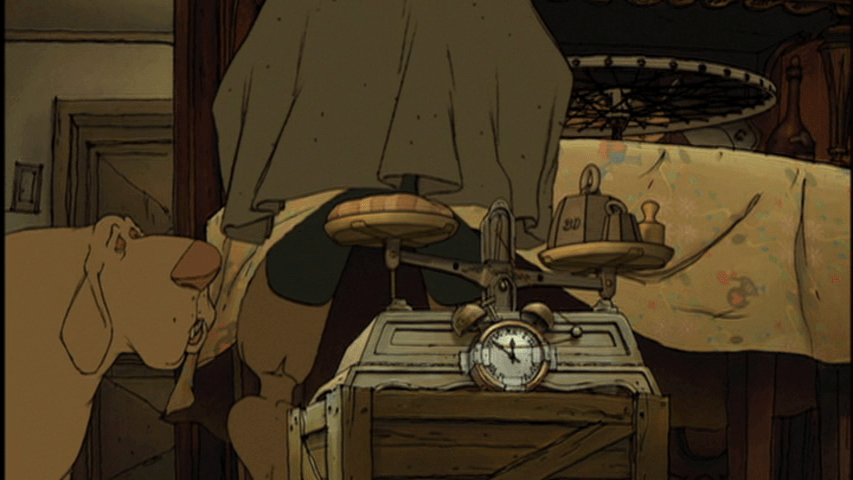

He consumes exactly as much food as his body needs, as determined by a scale hooked up to an alarm clock:

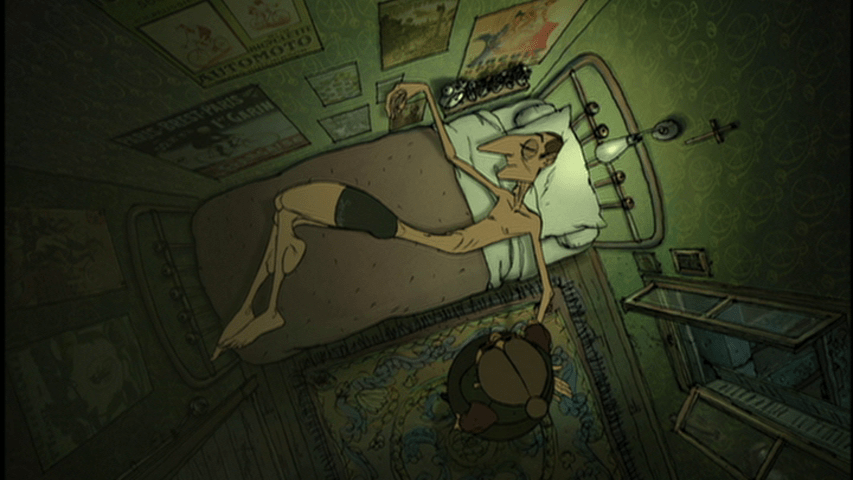

Bruno is watching so attentively because he’ll get whatever is left. Finally, it’s time for bed:

Following a brief glimpse of Bruno’s dreams, we are next transported to a Tour de France mountain stage. Madame Souza tracks Champion’s progress from the broom wagon (so named because it follows the race and “sweeps up” riders who aren’t able to finish in the time allotted) using binoculars:

Unlike the eventual winner, whom IMDb identifies as five-time Tour winner Jacques Anquetil, neither Champion nor Madame Souza ever cracks a smile.

Champion will ultimately prove unable to finish the stage, but this doesn’t register as failure. Now, to be sure, this is in part because he gets abducted, setting off the film’s second act; however, there’s also a very strong sense that it wouldn’t have been mattered anyway. This, as much as the images, is what makes The Triplets of Belleville such a great depiction of the Tour de France. The finishes are very dramatic, yes, but I also love how much else is always going on. It doesn’t just matter who wins the stage, it also matters who wins each climb and intermediate sprint along the way, because while a small subset of GC (or “General Classification”) riders are competing for first place overall, others are competing for King of the Mountain or points leader. Yet others are trying to be the most successful rider under 26 years of age or the most combative rider. Most riders don’t even aspire to win anything for themselves, but rather are there to help their team or individual teammates.

In other words, the Tour de France isn’t a simple race, but rather a whole suite of competitions, each with its own set of strategies, rivalries, and drama. It’s impossible to tell from the film what exactly Champion is in the race to do. Maybe he exhausted himself early in the stage helping his team leader over a tough climb. Maybe he’s a sprinter and it was always going to be a struggle to finish this portion of the race. What we do know is that he, like everyone else in the race, devoted the better part of his life to the pursuit of just getting there in the first place. And although it isn’t necessarily written all over his or his grandmother’s faces, it’s obvious that this has given their lives structure and meaning and that they are happy as an old cabaret singer with a frogsicle.

Cheers!

All original photographs in this post are by Marion Penning, aka My Loving Wife. Other entries in this series can be found here.