Alison Willmore opens her review of Inside Out 2 with a question:

Are all the personified emotions that scurry around inside the head of the movie’s young heroine supposed to be an allegory for her developing consciousness? Or is Riley actually being controlled by whatever adorable cartoon has seized the console at the moment, like she’s a mecha in the shape of a 13-year-old girl?

She notes that after the first Inside Out movie she would have said the former, but isn’t so sure now that she has seen its sequel. This was my initial impression as well, and I thought that it marked Inside Out 2 as being inferior. Then I read Maya Phillips’ New York Times article about how its depiction of anxiety is true to her own experience, specifically the way the emotion with that name voiced by Maya Hawke banishes Joy (Amy Poehler) and the other feelings which constituted the original film’s main characters from the helm of Riley’s mind. She proposes that this is one of its chief virtues:

Perhaps ‘Inside Out 2’ is providing children with a peek into the future, not as a prophecy of doom but as a route to understanding an emotion that has become more recognizable and prevalent in people of all ages.

Maybe the upshot is that when young ‘Inside Out’ fans inevitably become caught in one of those brutal storms of anxious thoughts, they can then summon a clear image of the chaos of their mind, as though it’s a bright, colorful Pixar film. Maybe then they can recognize that orange bearer of dreadful tidings and gently guide her to a seat.

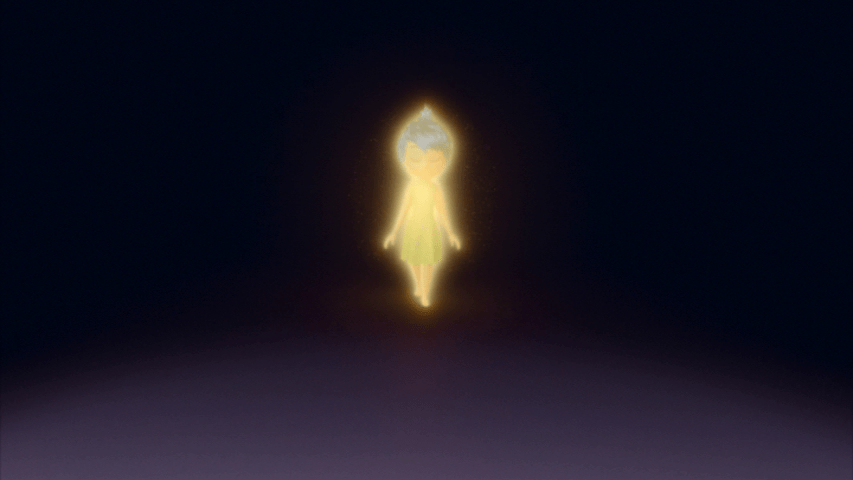

Phillips’ reading lends itself to either answer to Willmore’s questions, but thinking through which one is a better fit drew my attention to something intriguing. Joy is pretty clearly the leader of Riley’s emotions until Anxiety supplants her. She’s the first one to appear, minutes after Riley is born:

At first the console has but one button, and when Joy pushes it, baby Riley laughs:

33 seconds later, she starts to cry, which is when Joy realizes she has company:

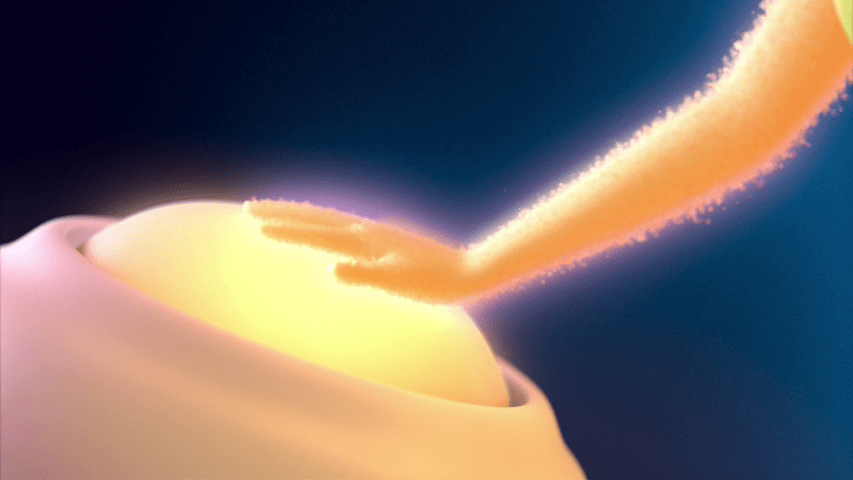

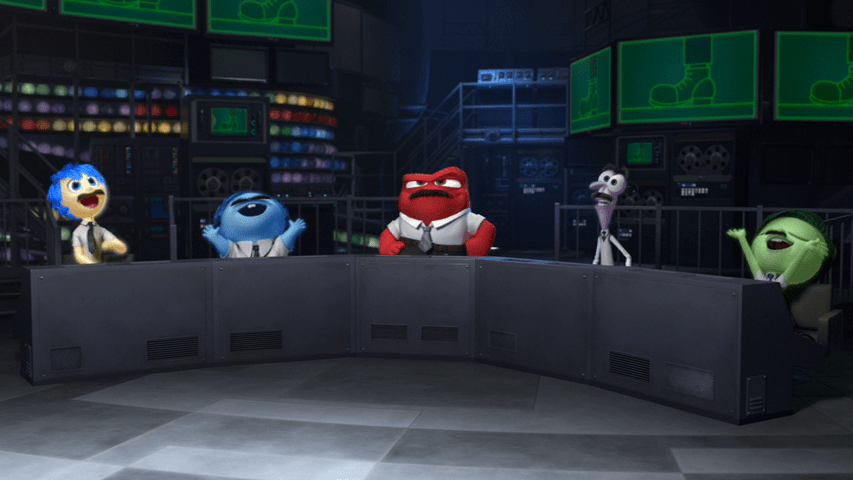

Joy and Sadness (Phyllis Smith) are soon joined by the other OG emotions, Fear (Bill Hader in the first movie, Tony Hale in the second), Disgust (Mindy Kaling/Liza Lapira), and Anger (Lewis Black). Each has the ability to take control, and as Phillips notes the console changes to purple, green, or red respectively when they do:

Joy spends the most time in the driver’s seat, though, and the other emotions also look to her for direction. What’s interesting about this situation is that it appears to have parallels in the control centers of most of the other humans we get glimpses of. Sadness (Lori Alan) occupies the center position both times we see Riley’s mother’s mind, for instance:

And her father’s emotions go so far as to address Anger (director Pete Docter) as “sir”:

This does not seem to be explained by the fact that her mom and dad are feeling sadness or anger in these scenes because they aren’t, really. Although the one other human mind we see during the movie proper is completely unhelpful because the emotions in the mind of the adolescent boy Riley talks to are in a state of panic at being addressed by a girl:

The minds of Riley’s teacher, a barista, and a clown that we see during the end credits do seem to support this interpretation:

There’s even a provocative suggestion that these are healthy, adult minds where the chief emotion has learned to listen to the others in the form of a contrasting peek inside the brain of a “cool girl” where Fear gets pushed out of the way by Anger in a manner reminiscent of the way Joy initially treats Sadness:

I can’t help but wonder what determines which emotion is ascendent. Is it just whichever one appears first? If so, this would justify Phillips’ support for the fact that in the Inside Out universe controlling your anxiety looks like “sitting her down in a cozy recliner with a cup of tea.” But could a person who isn’t anxious all the time have a mind where Anxiety is in the driver’s seat but takes advice from other emotions in much the same way that Sadness and Anger do in the case of her parents? Suddenly I find myself eager to spend some time with Inside Out 2 after it comes out on DVD (hence the “Part One” in the title of this post) to see if it offers any hints! In the meantime, I’ve found a satisfactory explanation for what had been my least favorite moment in the first film because I couldn’t make sense of it, the way Riley’s control panel starts to go dark and become unresponsive when she decides to run away from home:

As fun as all of this detective work is, Inside Out cautions us not to take it *too* literally. Take, for instance, this joke about what the mind of a school bus driver looks like:

Or these depictions of the brains of a dog and cat:

I like the idea of a generation of young people growing up with more mastery of their potentially destructive feelings thanks to these movies, but where they resonate with me most is as a representation of the experience of being a parent: the films’ personified emotions, whichever one is “driving,” all want to be part of their person’s life so that they can help them grow up into a strong, independent adult. The lesson of the runaway scene is that this requires balance, care, and maybe a bit of luck: if you’re either too preoccupied with your own life or too pushy, you risk losing them forever.

12/27/24 Update: Part Two of this post can be found here.