Eighteen minutes into Groundhog Day, weatherman Phil Connors (Bill Murray) sits in the bar of the Pennsylvanian Hotel and orders “one more of these with some booze in it”:

Judging from its appearance and subsequent scenes, the drink in question is most likely Jim Beam on the rocks with a splash of water, which Phil orders from the same bar later in the movie, using his fingers to indicate exactly how much of each component he wants:

It might also be Jack Daniels, which I think is what he is swigging from the bottle in this scene:

Either way, Phil seems to be partial to whiskey. His producer Rita (Andie MacDowell) is not: her tipple of choice, as we learn from her first drink order, is “sweet vermouth on the rocks with a twist.” Upon discovering that he is stuck in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania living the same day over and over, Phil decides to seduce Rita to pass the time. His plan begins back in the bar at the Pennsylvanian. “Can I buy you a drink?” he asks her. When she says yes, he not-so-innocently requests “sweet vermouth, rocks, with a twist, please.” After telling the bartender (John Watson Sr.) she wants the same, Rita turns to him with a smile. “That’s my favorite drink!” she exclaims. “Mine, too!” he replies with mock astonishment. “It always makes me think of Rome, the way the sun hits the buildings in the afternoon.” He proposes a toast to the groundhog, but it falls flat (more on this in a bit):

So he takes a sip of his drink. It’s the face he makes next that I want to talk about first:

Obviously, he’s not a fan. But why not, and what does it tell us? A good starting point is to try to determine what exactly they’re drinking. Unfortunately, the film itself is of little help in this regard. There’s only one good shot of the backbar at the Pennsylvanian:

You actually can make out quite a few labels: I see Jose Cuervo Especial, Bushmills Irish Whiskey, Kahlua, Glenlivit, and Absolut Peppar, for instance, but nothing clearly identifiable as sweet vermouth. There’s another shot in the film that theoretically could tell us something about what brands were available in Punxsutawney at the time, of the backbar at the German restaurant where Phil and Rita eat dinner later that evening, but it’s similarly unhelpful:

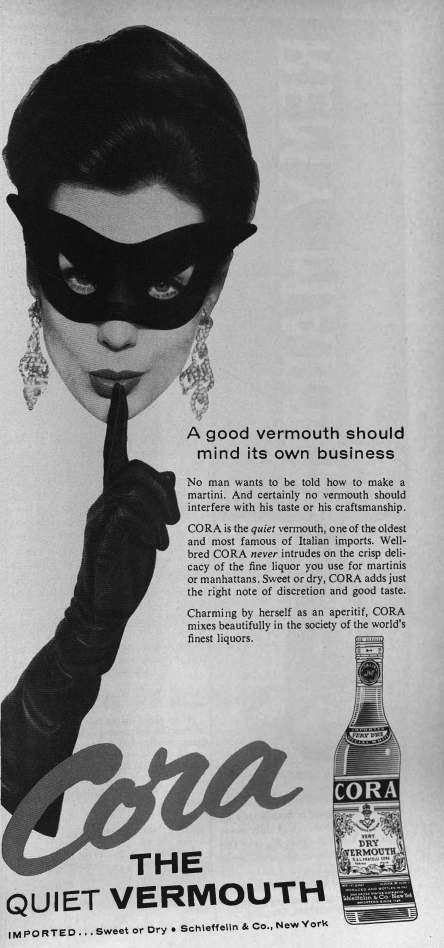

I see Maker’s Mark, J&B Scotch Whisky, Tanqueray, Frangelico, and a few other things here, but again, no vermouth. Even lacking a smoking gun, though, I think we can make some strong inferences. As chronicled by Adam Ford in his book Vermouth: The Revival of the Spirit that Created America’s Cocktail Culture, vermouth had its heyday in the United States in the 1930s and 40s. While Helen Weaver describes drinking “sweet vermouth on the rocks with a twist of lemon” at a Greenwich Village lesbian bar called The Bagatelle as late as 1955 in The Awakener: A Memoir of Jack Kerouac and the Fifties, according to Ford the spirit had been in decline since the end of World War II, and its fall from grace was expedited shortly afterward when foreign producers began reformulating the vermouths they exported to the United States into less flavorful styles marketed as a perfect complementary ingredient in cocktails like the martini and manhattan. The reason? “As men returned from the war and found women in increasingly powerful roles, a faux-masculinity appeared, which resulted in men demanding ‘stronger’ drinks” (Vermouth, p. 110). This advertisement for Cora vermouth in the March 12, 1960 edition of The New Yorker (one of two brands of vermouth with ads in the issue!) cited by Ford says it all:

Bill Murray was born in 1950. If Phil is approximately the same age, then he would have grown up surrounded by messages like this one about how he should act and drink. Is it any wonder that he prefers reading Hustler to attending Punxsutawney’s annual Groundhog Dinner, that he’s incredulous at the idea that a man would cry in front of a woman, or that one of the ways he chooses to spend immortality is by living out this fantasy?

Is it any surprise that he would be disgusted by a weak, “girlie” drink like unadulterated sweet vermouth? In an article in the journal Critical Studies in Mass Communication called “The Spiritual Power of Repetitive Form: Steps Toward Transcendence in Groundhog Day,” Suzanne M. Daughton argues that the film “presents one man’s metaphorical journey away from the stereotypically masculine pursuit of Power and Agency” and toward “acceptance of Spirit and communion” by subverting “the traditional masculine theme of the romantic quest, where the hero must travel far away to meet his challenges” and replacing it with “a feminine initiation ritual” (p. 143). Proponents of this reading could plausibly see Phil’s reaction as one of the pivotal moments in the film: he recoils from its bitter taste, but his medicine has been taken.

A more charitable explanation for Phil’s reaction is suggested by his reference to Rome. Adam Ford begins his history of vermouth by talking about how he came to be interested in it:

When we got back down into the Aosta Valley about a week later, in the serene mountain town of Courmayeur, we rewarded ourselves with a fancy hotel room and an expensive dinner at a small side-street café, a little bit off the main town square. During dinner, my wife noticed that others in the restaurant were drinking vermouth, and of course she ordered a glass. We had never seen the brand before. She took it cellar temperature in a classic Italian wine glass, like everyone else, and loved it.

For the first time I tried it too, and found it unlike anything I’d ever drunk before. The flavors were intriguing, enigmatic, and distended. I asked the bartender (in Spanish) what the ingredients were and he told us (in Italian) that–as with all vermouths–it was a highly guarded secret, but that everyone had their opinions as to some of the ingredients. An Israeli couple next to us overheard and suggested a few possibilities: Maybe gentian? Or angelica? Certainly some cinnamon. The night ended with a list of almost a dozen potential candidates that I wrote down on the back of a napkin, sadly long since lost.

We closed out the restaurant, and despite the amount we had drunk, we walked back to our hotel room still sober and excited, holding hands like a couple of junior-high kids. While I looked at her and she looked toward the stars, I asked Glynis what she wanted to do when we got back to America. She said she wanted more nights like the one we just had.

Ford goes on to note that when they returned to the United States, they did start drinking more vermouth, but that the only ones they were able to find paled in comparison to what they had consumed in Europe: “[t]hey were like buying a suit off the rack after years of having tailor-made; it was fine, but you didn’t feel like you were at the top of the food chain.” An experience like this is plausibly how Rita and the real-life inspiration for her drink order (as described in the director’s commentary on the special edition DVD), Harold Ramis’s wife, came to develop their preferences for vermouth as well. If we assume that, like Bill Murray’s character in Scrooged, Phil wasn’t always a jerk, maybe he, too, has a memory that the drink he is served at the Pennsylvanian just can’t live up to.

The most likely solution may be the simplest one, though. Good vermouths like Punt e Mes, a personal favorite which is mentioned in a New York Times article dated November 1, 1992, definitely were being exported to the United States in the early 1990s when Groundhog Day is set, but it’s unclear whether or not they would have been available in rural Pennsylvania. It seems far more probable that Phil and Rita would have been served a major global brand like Martini & Rossi (which was acquired by Bacardi Ltd. just a few months before the film was released in a move that the Wall Street Journal reported created the world’s fifth-largest wine and spirits company) or a bottom-shelf American label like Tribuno, which I remember collecting dust on my parents’ home bar in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. That bottle from my youth was almost certainly purchased from a state store supplied by the same Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board that the commercial establishments in Punxsutawney would have been legally required to buy their spirits from. In other words, the drink may just not have been very good. And that, finally, brings me back to Phil’s toast.

Recall that Phil and Rita are sitting in a bar in the hometown of Punxsutawney Phil, “the world’s most famous weatherman,” on Groundhog Day. Phil offers to buy Rita a drink. She accepts. She asks him, “well, what should we drink to?” He responds, “to the groundhog!” This is entirely appropriate under the circumstances, but what does Rita do? She gives him a disappointed look:

And says, “I always drink to world peace.” Maybe the film makes a joke out of Rita’s bad taste in booze, maybe it doesn’t: I don’t think it’s saying anything significant about her either way. But what are we supposed to make of a person who reacts this way to a perfectly respectable toast?

To quote Adam Ford one last time, the genius of the inventor of vermouth, Antonio Benedetto Carpano, was that he “perfected a drink that hit upon the two most popular flavors at the time: sweet and bitter” (p. 66). There are beautiful scenes in Groundhog Day. Here’s one I’m particularly fond of:

But treacle needs to be cut, as Danny Thomas once said to Time magazine, and that’s what moments like Rita’s reaction to Phil’s toast accomplish. After all, she may look like an angel when she stands in the snow, but she isn’t one: she’s a human being with flaws, and however well Phil knows Rita by the end of February 2, February 3 is a new day and only the second one she’s ever spent with him. And so, “let’s live here!” Phil says at the end of the film. But then, immediately afterward: “we’ll rent to start.” To quote the Nat King Cole song which plays over the credits with a slight change in emphasis, it’s almost like being in love.

Real bars keep sweet and dry vermouth in the cooler or fridge. Vermouth is a fortified wine, once you open the bottle it starts to oxidize. Keeping it cool will extend the life of the liquid, after a month it will turn which is why so many don’t like it. Nit many, especially Americans, know how to store vermouth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry for the delayed response, Ryan, and thanks for the comment! This is an excellent point. It may explain why we can’t see any bottles of vermouth on display at the Pennsylvanian. Or, if we don’t consider it to be a “real bar,” maybe this provides further support for the theory that the vermouth they serve Phil isn’t very good. Definitely it explains my lack of nostalgic fondness for Tribuno!

LikeLike