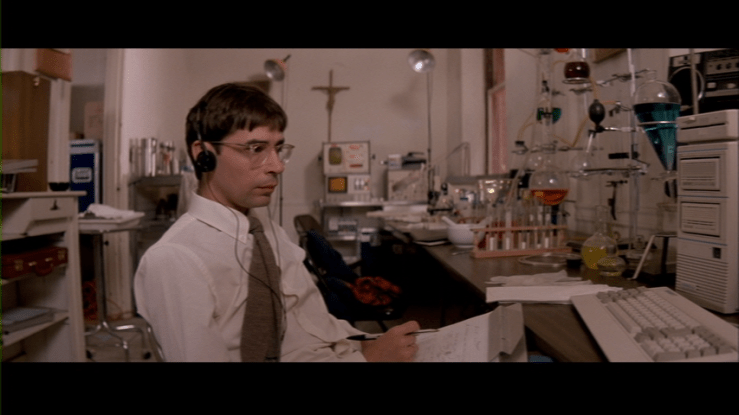

I’ve been thinking a lot about this character in John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness lately. His name is Etchinson (not that anyone ever addresses him as such–we have to wait until the end credits to find this out) and he’s played by the actor Thom Bray. He is on screen for 4:08 total in a film with a 102 minute runtime (~3% of the whole), and all of his appearances are confined to the 11 minutes (~9%) between the 26:36 and 37:38 marks. We know that he is a graduate student, and that his discipline is biochemistry. That’s about it, though.

His chief claim to fame is, of course, being the first person in the film to be killed:

Part of what makes him memorable is how he goes, impaled on a bicycle in an impressive stunt borrowed from Alice Cooper’s stage show (per Gilles Boulenger’s John Carpenter: The Prince of Darkness, p. 204) by a “street schizo” played by Cooper himself:

It’s a sudden, brutal death to be sure, but so are many others in the film: why is this the one that stuck with me? First, at the risk of being obvious, the scene is well done. In addition to the stunt work mentioned above, this is a good example of the director’s mastery of what Michelle Le Blanc and Colin Odell call “the act of depicting nothing” in their book John Carpenter. As they note, “[a]n empty room is ominous because cinema is generally concerned with action–emptiness represents suspicion or disruption of order” (p. 19). In the case of Prince of Darkness, anticipation is created by the inaction of the homeless people who have been arriving at Saint Godard’s (the church where the bulk of the film’s action is set) in greater and greater numbers since Etchinson and his colleagues began appearing, and who are described thusly seconds before Etchinson exits the film:

KELLY: Now, a friend of mine at UCLA did a study of chronic schizophrenics. They’re supposed to have stereotyped routines that they repeat every 20 minutes or so, you know, like a stuck record in their brains repeating the same phrase over and over. Well, I have been watching them on and off all day, and they don’t seem to be making any movements. They just stand there.

Second, the scene remains effective even after you’ve seen the rest of the movie; in fact, if anything, it’s more surprising in retrospect than it is in the moment. A viewer familiar with Robin Wood’s ideas about the horror genre and the “return of the repressed” (as articulated in his book Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan and elsewhere) or the rules for surviving a horror movie presented in Scream could be forgiven for assuming that Etchinson was chosen as the first victim as punishment for the promiscuity implied by his one memorable line: “how married?” he asks after being told that the attractive young woman he has just inquired after is spoken for. The subsequent carnage doesn’t follow anything like this pattern, however, and in the end it seems that Etchinson is guilty of nothing more than being in the wrong place at the wrong time (and possibly of being a graduate student, who are, as we know, the worst).

More than just being random, though, this points to the most disturbing aspect of what Etchinson’s demise implies. John Carpenter is famously enamored of the work of Howard Hawks: his second full-length feature Assault on Precinct 13, for instance, is essentially a remake of Hawks’s Rio Bravo. In a Hawksian universe, survival depends on being “good enough” or, if you’re not, understanding your limitations and staying within them. Etchinson’s murder is our first clear indication that, unlike other Carpenter movies, Prince of Darkness is not set in such a universe. To quote the film’s Professor Birack (Victor Wong), “while order does exist in the universe, it is not at all what we had in mind!” In other words, being good enough might not be good enough to make it out alive.

Writing in Film Comment, Kent Jones observed that John Carpenter is “one of the few modern artists whose subject is the contemplation of true evil” and that in contrast to Hawks, “where all the energy goes into the beauty of people in action,” Carpenter’s films “are filled with moments of paralyzing immobility, of dry-mouthed discomfort brought about by the realization that there is something new and awful in the world.” Etchinson actually freezes three times in his final scene: once when he sees this crucified pigeon:

Once when he realizes he’s surrounded, and one last time the moment he understands he’s about to die. This is, I think, exactly what Jones was talking about, and that’s what makes Etchinson such a memorable character despite his limited screen time: he’s a perfect example of some of the most interesting and original aspects of Carpenter’s artistic vision.